John James Audubon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John James Audubon

|

|

|---|---|

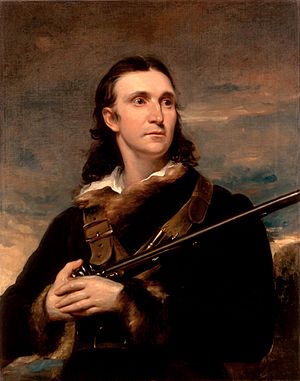

Portrait of Audubon by John Syme, 1826

|

|

| Born |

Jean-Jacques Rabin

April 26, 1785 |

| Died | January 27, 1851 (aged 65) New York City, New York, U.S.

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Occupation | Artist, naturalist, ornithologist |

| Spouse(s) |

Lucy Bakewell

(m. 1808) |

| Signature | |

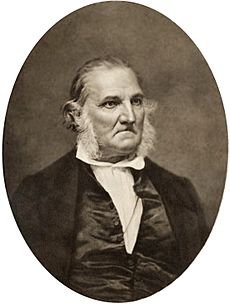

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin; April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was a French-American artist, naturalist, and ornithologist. He taught himself about nature and art. Audubon loved both art and birds. He decided to draw every single bird species in North America.

He became famous for his detailed drawings of American birds. His pictures showed birds in their natural homes. His most famous work is a book called The Birds of America (1827–1839). Many people think it's one of the best bird books ever made. Audubon also found 25 new bird species. The National Audubon Society, which helps protect birds, is named after him. Many towns and streets in the United States also carry his name.

Contents

- Audubon's Early Life

- Moving to the United States

- Bird Banding Story

- Marriage and Family Life

- Starting a Business

- Becoming a Citizen and Facing Challenges

- Early Bird Studies

- The Birds of America Publication

- Later Career and Final Works

- Audubon's Death

- Audubon's Art and Methods

- Audubon's Legacy

- Works by Audubon

- See also

Audubon's Early Life

Audubon was born in Les Cayes. This was a French colony called Saint-Domingue, which is now Haiti. His father, Jean Audubon, owned a sugarcane plantation. His mother, Jeanne Rabine, died when he was a baby.

His father was a French naval officer. He worked hard to save money for his family. Because of problems in Saint-Domingue, he sold part of his plantation in 1789. He bought a farm in Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia. In 1788, his father sent young Jean to France.

Jean and his half-sister, Muguet, were raised in Couëron, France. His father and his French wife, Anne Moynet Audubon, adopted them. They renamed the boy Jean-Jacques Fougère Audubon.

From a very young age, Audubon loved birds. He felt a strong connection to them. He said this feeling would stay with him his whole life.

During the French Revolution, Audubon grew up to be a friendly young man. He enjoyed playing music and outdoor activities. He loved exploring the woods. He often brought back bird eggs and nests. He would try to draw them. His father wanted him to be a sailor. But Audubon didn't like being on ships or studying math. So, he stopped his naval career. He went back to exploring nature and focusing on birds.

Moving to the United States

In 1803, when he was 18, Audubon's father helped him get a fake passport. This was so he could go to the United States. He wanted to avoid being forced to join the army during the Napoleonic Wars. Jean-Jacques changed his name to John James Audubon.

When he arrived in New York City, Audubon got sick. Some kind Quaker women helped him get better. They also taught him English. He then traveled to his family's farm, Mill Grove, in Pennsylvania.

Audubon loved the farm. He spent his time hunting, fishing, drawing, and playing music. He felt no worries there. He quickly learned that the type of place, like whether it was wet or dry, helped him guess what animals lived there.

His father hoped that lead mines on the farm could make money. This would give his son a good job. At Mill Grove, Audubon met Lucy Bakewell, who lived nearby.

Audubon started to study American birds. He wanted to draw them more realistically than other artists. He drew and painted birds and watched how they behaved. After falling into a creek, he got a bad fever. Lucy helped nurse him back to health.

In 1805, Audubon went back to France to see his father. He also wanted to ask permission to marry Lucy. While there, he met Charles-Marie D'Orbigny. D'Orbigny taught Audubon how to prepare animal specimens for display.

Audubon continued his bird studies. He created his own nature museum, full of bird eggs, stuffed animals, and other creatures. He became very good at preparing specimens. With his father's approval, he sold part of the Mill Grove farm.

Bird Banding Story

In a book from 1834, Audubon told a story from his childhood. He said that in 1804, he found a nest of "Pewee Flycatchers" (now called Eastern Phoebes). He said he put small rings on their legs. He later claimed that two of these birds returned the next spring. This story made him known as the "first bird bander in America."

However, later research showed that Audubon was in France during the spring of 1805. This means he couldn't have been in Pennsylvania to see the birds return. Also, modern studies show that very few young phoebes return to the same spot. These facts make Audubon's story seem unlikely.

Marriage and Family Life

In 1808, Audubon moved to Kentucky. Six months later, he married Lucy Bakewell in Pennsylvania. They moved to Kentucky the next day. They both loved exploring nature.

Audubon and Lucy had two sons, Victor Gifford and John Woodhouse Audubon. They also had two daughters who died when they were very young. Both sons later helped their father publish his works. John W. Audubon also became a naturalist and artist.

Starting a Business

Audubon and his business partner, Jean Ferdinand Rozier, moved their store west. They ended up in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri. They first opened a general store in Louisville, Kentucky. Audubon soon started drawing bird specimens again. He often burned his old drawings to make sure he kept improving. He also wrote detailed notes about his drawings.

In 1810, Audubon moved his business to Henderson, Kentucky. He and his family lived in an old log cabin. Audubon often hunted and fished to feed his family. He wore frontier clothes and moccasins.

He met Shawnee and Osage hunting groups. He learned their ways and drew animals by the campfire. Audubon respected Native Americans greatly. He also admired the skills of Kentucky hunters.

Audubon and Rozier ended their business partnership in 1811. Audubon wanted to focus on his art and bird studies.

Audubon was in Missouri when the powerful New Madrid earthquake happened. He was relieved to find his house was not badly damaged. The area had many smaller quakes for months. The earthquake was very strong, even stronger than the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Becoming a Citizen and Facing Challenges

In 1812, Audubon became an American citizen. He had to give up his French citizenship. When he returned to Kentucky, he found that rats had eaten over 200 of his drawings. He was very sad, but he started drawing again. He was determined to make his new drawings even better.

The War of 1812 changed Audubon's business plans. He started a new business with Lucy's brother in Henderson. Times were good for a while. But after 1819, Audubon went bankrupt. He was even put in jail for debt. He earned a little money by drawing portraits. He wrote that even in hard times, he was developing his artistic talents.

Early Bird Studies

Audubon worked for a short time at The Museum of Natural History in Cincinnati. Then he traveled south along the Mississippi River. He had his gun, paintbox, and an assistant, Joseph Mason. Mason helped him by painting the plants in the backgrounds of his bird pictures. Audubon was determined to find and paint all the birds of North America. He wanted his work to be better than Alexander Wilson's bird studies.

In 1820, Audubon traveled through Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. He was looking for bird specimens. He worked at Oakley Plantation in Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. He taught drawing to the owner's daughter. This job was perfect because it gave him lots of time to paint in the woods. (You can still visit this plantation today as the Audubon State Historic Site.)

Audubon called his big project The Birds of America. He tried to paint one page every day. He realized his older works weren't good enough, so he redid them. He hired hunters to find birds for him. He knew this huge project would take him away from his family for many months.

Audubon sometimes traded his drawings for goods or sold small artworks for money. He drew charcoal portraits for $5 each. In 1823, he learned how to paint with oil paints. He earned good money painting oil portraits for people along the Mississippi.

Lucy became the main provider for their family. She was a teacher and taught classes at home. Later, she taught in Louisiana.

In 1824, Audubon went to Philadelphia to find a publisher for his bird drawings. He met Charles Bonaparte, who liked his work. Bonaparte suggested he go to Europe to get his bird drawings printed.

The Birds of America Publication

With his wife's support, Audubon took his drawings to England in 1826. He was 41 years old. He arrived in Liverpool with over 300 drawings. He had letters to important people in England. He quickly got their attention. He wrote, "I have been received here in a manner not to be expected during my highest enthusiastic hopes."

People in Britain loved Audubon's pictures of American nature. He traveled around England and Scotland. People called him "the American woodsman." He raised enough money to start publishing his book, The Birds of America.

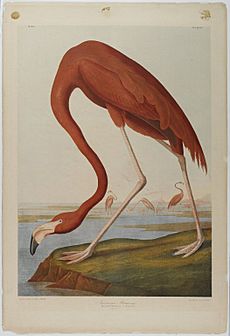

This huge book has 435 hand-colored prints. These prints show 497 different bird species. The pictures were made from engraved copper plates. The pages were very large, about 39 by 26 inches. The book shows more than 700 North American bird species. Some birds were based on specimens collected by another bird expert, John Kirk Townsend.

The pages were arranged to look artistic and interesting. The first and most famous picture was of a wild turkey. One of the first pictures printed was the "Bird of Washington." This picture helped Audubon get good publicity. He claimed it was a new species he discovered. However, no one has ever found a specimen of this bird. Some research suggests this picture was not entirely original.

The whole book cost a lot of money to print, over $115,000 (which is over $2,000,000 today!). Audubon paid for it by getting people to subscribe in advance. He also held exhibitions and sold oil paintings and animal skins. It took him more than 14 years of field work and drawing. He also managed and promoted the project all by himself.

Many people were hired to color the prints by hand. Robert Havell, Jr. did the engravings. The book is known as the Double Elephant folio because of its large paper size. It is often called the greatest picture book ever made. A French critic wrote that it was like being transported into the forests of the New World.

Audubon sold oil-painted copies of his drawings to earn more money. King George IV of Britain was a big fan. He subscribed to the book. Britain's Royal Society made Audubon a member because of his achievements. He was only the second American to be elected, after Benjamin Franklin.

While in Edinburgh, Audubon showed how he used wire to pose birds for his drawings. Student Charles Darwin was in the audience. Audubon also visited an anatomy theater. He was also successful in France. The French King and many nobles became subscribers.

The Birds of America became very popular in Europe. Audubon's dramatic bird portraits appealed to people's interest in nature.

Later Career and Final Works

Audubon returned to America in 1829 to finish more drawings. He also hunted animals and sent their skins to friends in Britain. He was reunited with his family. Lucy went back to England with him. Audubon found that some people had stopped subscribing to his book. He worked to fix the printing plates and reassure his subscribers. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1830.

After The Birds of America, he published Ornithological Biographies. This book had stories about each bird species. He wrote it with Scottish bird expert William MacGillivray. The two books were printed separately to avoid a British law.

During the 1830s, Audubon continued exploring North America. On a trip to Key West, a friend wrote that Audubon was very enthusiastic. He would wake up at 3 AM and go out until 1 PM. Then he would draw for the rest of the day. He kept this routine for weeks.

In 1841, Audubon returned to the United States with his family. He bought a large property in northern Manhattan, New York. He published a smaller, more affordable version of The Birds of America. This edition earned $36,000 and had 1100 subscribers. Audubon spent a lot of time traveling to sell this new edition. He wanted to make sure his family would have money.

Audubon's Death

Audubon made some trips out West to find more species. But his health began to get worse. By 1848, he showed signs of memory problems, possibly Alzheimer's disease. He died at his home in Manhattan on January 27, 1851.

Audubon is buried in the graveyard at the Church of the Intercession in Manhattan. A large monument was built in his honor there.

Audubon's last work was about mammals. It was called The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845–1849). He worked on it with his friend, Rev. John Bachman. His son, John Woodhouse Audubon, drew most of the pictures. His sons finished the second volume after Audubon's death.

Audubon's Art and Methods

Audubon created his own ways to draw birds. For a large bird like an eagle, he would spend up to four 15-hour days preparing, studying, and drawing it. His bird paintings show them in their natural homes. He often drew them as if they were moving, like when they were eating or hunting. This was different from other artists who drew birds in stiff poses.

Audubon based his paintings on what he saw in nature. He mostly used watercolors. He added colored chalk to make feathers look soft. He used many layers of watercolor. All birds were drawn life-size. This is why larger birds sometimes look twisted to fit on the page. Smaller birds were often placed on branches with berries or flowers. He sometimes drew several birds on one page to show different views. He often showed birds' nests and eggs. He also sometimes included animals that prey on birds, like snakes. He usually drew male and female birds, and sometimes young ones. Later, he had assistants draw the backgrounds for him. Audubon's art was not just scientifically accurate; it also had drama and artistic flair.

-

Plate 76 of The Birds of America by Audubon showing a northern bobwhite under attack by a young red-shouldered hawk, painted 1825

Audubon's Legacy

Audubon had a huge impact on the study of birds and nature. Almost all later bird books were inspired by his art and high standards. Charles Darwin even mentioned Audubon in his famous book On the Origin of Species. Even with some small mistakes in his notes, Audubon greatly helped people understand how birds look and behave. The Birds of America is still seen as one of the greatest art books ever. Audubon discovered 25 new bird species and 12 new types of birds.

- He became a member of important scientific groups like the Royal Society.

- His childhood home, Mill Grove in Audubon, Pennsylvania, is now a museum. It shows all his major works, including The Birds of America.

- The Audubon Museum in John James Audubon State Park in Henderson, Kentucky, has many of his original paintings and personal items.

- In 1905, the National Audubon Society was created and named after him. Its goal is to protect nature, especially birds.

- The US Post Office honored him with postage stamps in 1940 and later.

- In 2010, a copy of The Birds of America sold for $11.5 million. This was the second highest price ever for a printed book.

- On April 26, 2011, Google celebrated his 226th birthday with a special picture on its homepage.

- A 2017 film called Audubon was made about his life and work.

Places Named After Audubon

Many places are named in honor of John James Audubon:

- Audubon Park and Zoo in New Orleans, where he lived.

- The towns of Audubon and Audubon Park in New Jersey. Many streets there are named after birds he drew.

- Audubon, Pennsylvania, which also has the Audubon Bird Sanctuary.

- Audubon Middle School in Los Angeles, California.

- Audubon Nature Institute, a group of museums and parks in New Orleans.

- Audubon Park in Louisville, Kentucky.

- Several towns and Audubon County, Iowa.

- The John James Audubon Bridge (Mississippi River) in Louisiana.

- Audubon Park in Memphis, Tennessee.

- John James Audubon State Park in Henderson, Kentucky.

- The Audubon Parkway in Kentucky.

- Streets named Rue Jean-Jacques Audubon in Nantes and Couëron, France.

- Audubon Circle in Boston, Massachusetts.

- Audubon Avenue in New York.

- Audubon Bird Sanctuary in Dauphin Island, Alabama.

- Audubon National Wildlife Refuge in Coleharbor, North Dakota.

- Audubon Park in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- Scioto Audubon Metro Park in Columbus, Ohio.

- Mount Audubon in Colorado.

- Audubon High School in New Jersey, and many other schools.

- The Audubon Golf Trail in Louisiana.

- Audubon House & Gallery in Key West, Florida.

- Audubon Swamp Garden in Charleston, South Carolina.

Surviving Bird Specimens

Some of the bird specimens Audubon used still exist today. You can find them in museums like the Natural History Museum, London, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and the World Museum in Liverpool.

Works by Audubon

Books Published After His Death

- John James Audubon, Selected Journals and Other Writings (1996)

- John James Audubon, Writings & Drawings (1999)

- John James Audubon, The Audubon Reader (2006)

- Audubon: Early Drawings (2008)

- John James Audubon, Audubon and His Journals, edited by Maria Audubon (1897)

See also

In Spanish: John James Audubon para niños

In Spanish: John James Audubon para niños

- Audubon House and Tropical Gardens, Key West, Florida

- Audubon International

- Audubon Mural Project

- Audubon Park Historic District, New York City

- Audubon State Historic Site, West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana

- List of wildlife artists

- National Audubon Society

- Passenger pigeon

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |