Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony) facts for kids

The Pilgrims, also called the Pilgrim Fathers, were a group of English settlers. They traveled to North America on a ship named the Mayflower. In 1620, they started the Plymouth Colony in what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts.

The leaders of the Pilgrims were members of a religious group known as Separatists. They left England because they wanted to practice their religion freely. At that time, people in England were expected to follow the Church of England. The Pilgrims first moved to the Netherlands to find safety. Later, they decided to cross the Atlantic Ocean to establish a new community in the New World. Their story is a very important part of the history of the United States.

Contents

History of the Pilgrims

Leaving England

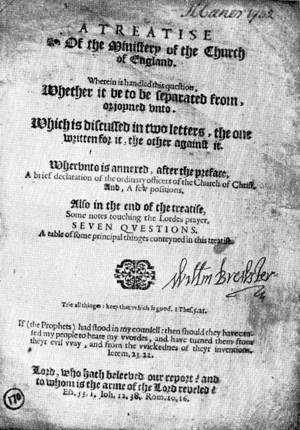

Around 1605, a group of people in Nottinghamshire, England, decided to leave the Church of England. They were led by John Robinson, Richard Clyfton, and John Smyth. These people were called Separatists. They believed that individual churches should be independent and democratic. They did not want to follow the rules of a large, central church like the Church of England.

Being a Separatist was dangerous. The laws in England said everyone had to go to the official church services. If they did not go, they had to pay money (fines) or could be sent to prison. Some Separatists were even put in jail for holding their own private church meetings. Because of this unfair treatment, the group decided to leave England. They wanted to go to a place where they could worship God in their own way without fear.

Life in the Netherlands

Around 1607 and 1608, the Pilgrims moved to the Netherlands. They settled in the city of Leiden. Leiden was a busy city with a university and many industries.

Life in Leiden was safe, but it was also hard. Many of the Pilgrims had been farmers in England. In the city, they had to work in cloth making, printing, or other trades. They had to work very hard just to earn enough money to live.

After about ten years, the leaders began to worry. They saw that their children were growing up speaking Dutch and adopting Dutch customs. They feared their group would disappear if they stayed. They also wanted to spread their religious beliefs to other parts of the world. They decided it was time to move again, this time to America.

The Voyage to America

The Pilgrims planned to take two ships: the Speedwell and the Mayflower. They left the Netherlands and went to England to get ready. However, the Speedwell was leaking and was not safe for the ocean voyage. They had to leave it behind.

Many passengers moved onto the Mayflower. On September 16, 1620, the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, England. There were 102 passengers on board. About half of them were Separatists (the "Saints"). The others were people hired to help build the colony or who wanted a new life (the Pilgrims called them "Strangers").

The trip across the Atlantic Ocean was very difficult. The ship was crowded, and the weather was often stormy. One storm was so bad it cracked a main beam in the ship. The crew had to fix it with a large iron screw to keep the ship from breaking apart. One passenger, John Howland, fell overboard during a storm but was saved when he grabbed a rope trailing in the water.

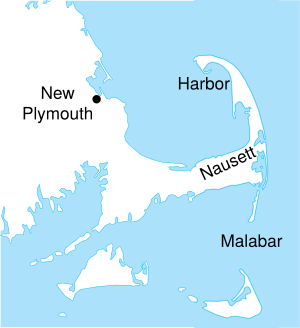

After 65 days at sea, they saw land on November 9, 1620. They had arrived at Cape Cod.

Arrival and Settlement

The Pilgrims originally planned to land near the Hudson River, further south. However, dangerous shallow water and currents stopped them from sailing there. They decided to stay at Cape Cod. They anchored the ship in Provincetown Harbor on November 21.

The Mayflower Compact

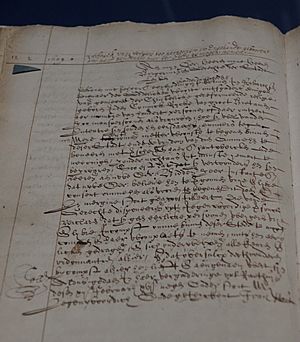

Because they landed in a place different from where they had permission to settle, some passengers thought they did not have to follow any rules. To prevent problems, the adult men on the ship signed an agreement. This document is known as the Mayflower Compact.

In the Compact, they agreed to:

- Form a government together.

- Create fair laws for the good of the colony.

- Obey these laws.

This was an early form of democracy in America. John Carver was chosen as the first governor of the colony.

Building Plymouth Colony

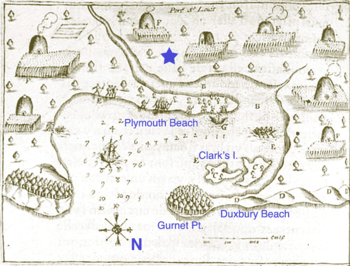

The Pilgrims spent weeks exploring the coast to find a good place to live. On December 21, 1620, they chose a site that had a good harbor and cleared fields. They named it Plymouth.

The first winter was terrible. The weather was cold and snowy. Many people got sick with scurvy and other diseases. They stayed on the ship while building their first houses. By the end of the winter, nearly half of the 102 passengers had died.

Meeting Native Americans

The land where the Pilgrims settled was known as Patuxet to the Wampanoag people. Sadly, a sickness had killed most of the people in that village a few years before the Pilgrims arrived.

In March 1621, a Native American named Samoset walked into the colony and spoke to them in English. He introduced them to Squanto (Tisquantum). Squanto spoke English very well because he had been kidnapped and taken to England years before.

Squanto helped the Pilgrims survive. He taught them how to:

- Plant corn using fish as fertilizer.

- Catch fish and eels.

- Find food in the forest.

Squanto also helped them make a peace treaty with Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag people. This treaty promised that they would not hurt each other and would help each other if attacked. This peace lasted for many years.

In the autumn of 1621, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag people shared a harvest feast. This event is celebrated today as the first Thanksgiving.

Why Are They Called Pilgrims?

The settlers did not call themselves "Pilgrims" at first. They called themselves "Saints" or "First Comers."

The name comes from a book written by William Bradford, a leader of the colony. He wrote about their departure from Leiden and said, "they knew they were pilgrims." He was referring to a passage in the Bible that describes people who are travelers on a spiritual journey.

Over time, people started using the name "Pilgrims" to honor the settlers. By the 1800s, it became the common name for the people who sailed on the Mayflower.

See also

In Spanish: Padres peregrinos para niños

In Spanish: Padres peregrinos para niños