Retreat from Gettysburg facts for kids

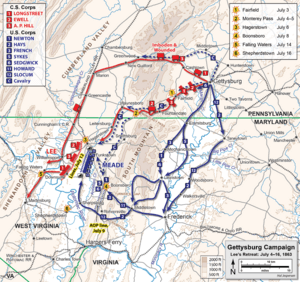

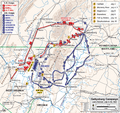

The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began its Retreat from Gettysburg on July 4, 1863. After General Robert E. Lee failed to win the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), he ordered his army to go back through Maryland and cross the Potomac River. Their goal was to reach safety in Virginia.

The Union Army of the Potomac, led by Major General George Meade, could not move fast enough to launch a big attack on the Confederates. Lee's army crossed the river on the night of July 13. They went through South Mountain and Cashtown. Their wagon train, carrying supplies and wounded soldiers, stretched for 15–20 miles. The journey was hard, with bad weather, rough roads, and enemy cavalry attacks.

Most of Lee's soldiers marched through Fairfield and over the Monterey Pass towards Hagerstown, Maryland. When they reached the Potomac River, they found the water was too high. Also, their pontoon bridges (temporary bridges) were destroyed. This meant they could not cross right away.

The Confederates quickly built strong defenses. They waited for the Union army, which was chasing them on longer roads to the south. Before Meade could properly check the defenses and attack, Lee's army escaped. They crossed the river using shallow parts (fords) and a quickly rebuilt bridge.

During the retreat, there were many smaller fights. These were mostly cavalry battles, raids, and skirmishes. They happened at Fairfield (July 3), Monterey Pass (July 4–5), Smithsburg (July 5), Hagerstown (July 6 and 12), Boonsboro (July 8), Funkstown (July 7 and 10), and around Williamsport and Falling Waters (July 6–14).

Even after crossing the Potomac, there were more clashes. These took place at Shepherdstown (July 16) and Manassas Gap (July 23) in Virginia. These fights marked the end of the Gettysburg Campaign of June and July 1863.

Contents

Why Lee's Army Retreated

The Battle of Gettysburg lasted three days. It ended with a huge attack called Pickett's Charge. In this attack, Confederate soldiers tried to break through the Union line. But they were pushed back and lost many men.

After this, the Confederates went back to their positions. They got ready for a Union counterattack. But by the evening of July 4, the Union army had not attacked. Lee realized he could not win anything more at Gettysburg. He knew he had to take his tired army back to Virginia.

His army was running low on supplies. They could not find enough food or resources in Pennsylvania. The Union army could easily get more soldiers, but Lee could not. Lee's artillery chief told him they had used up all their long-range cannon ammunition. Even though the Confederates had lost over 20,000 men, their spirits were still high. They still respected General Lee.

Lee started planning his retreat on the night of July 3. He moved his troops closer together. He also had his men build defenses like breastworks and rifle pits. These stretched for about 2.5 miles.

He decided to send his long train of wagons first. These wagons carried equipment, supplies, and about 8,000 wounded soldiers who could travel. Some important generals who were badly hurt but too important to leave behind also went with the wagons. Most of the Confederate wounded, over 6,800 men, stayed behind. Union doctors treated them in field hospitals.

The Retreat Routes

Lee's army had two main ways to cross South Mountain into the Cumberland Valley. This valley was the name for the Shenandoah Valley in Maryland and Pennsylvania. From there, they would march south to cross the Potomac River at Williamsport, Maryland.

One route was the Chambersburg Pike, which went through Cashtown towards Chambersburg. The other was a shorter route through Fairfield and over Monterey Pass to Hagerstown.

Luckily for Lee's army, their cavalry (soldiers on horseback) was now fully with them. The cavalry could scout ahead and protect the army. Earlier in the campaign, their cavalry commander, Major General J.E.B. Stuart, was separated from the army.

However, once the Confederates reached the Potomac River, they faced a big problem. Heavy rains on July 4 caused the river at Williamsport to flood. This made it impossible to cross by walking through the water (forging). Four miles downstream at Falling Waters, Union cavalry destroyed Lee's lightly guarded pontoon bridge on July 4. The only way to cross the river was a small ferry at Williamsport. This meant the Confederates could get trapped, forced to fight Meade's army with their backs to the river.

The Armies Involved

The Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia kept their main structures. By July 10, the Union army had about 80,000 men. They had replaced some of their losses from the battle. The Confederates did not get any new soldiers during the campaign. They had only about 50,000 men left.

Union Army Changes

The Army of the Potomac had many changes in its leadership because of battle losses. For example, Major General Daniel Butterfield, Meade's chief of staff, was wounded. Major General Andrew A. Humphreys replaced him. Major General John F. Reynolds was killed and replaced by Major General John Newton.

Besides battle losses, many Union soldiers left the army because their enlistment time was over. This happened even during the campaign. Also, thousands of Union soldiers needed food. The army's horses and mules needed boots, food, and shoes.

On the good side, Meade got about 10,000 temporary new soldiers. These men had been with General William H. French at Maryland Heights. They joined the Union I Corps and III Corps. In total, about 6,000 men were added to the Army of the Potomac. Including forces around Harpers Ferry and South Mountain, between 11,000 and 12,000 men joined the army by July 14. However, Meade doubted how well these new troops could fight.

Other Union forces were also nearby. Major General Darius N. Couch had 7,600 men at Waynesboro, 11,000 at Chambersburg, and 6,700 at Mercersburg. These were "emergency troops" raised quickly when Lee marched into Pennsylvania. They were under Meade's command. Also, about 6,000 men from the new Department of West Virginia were ready to stop Confederate forces from retreating west. They also helped chase Lee towards Virginia.

Confederate Army Leaders

Lee's Army of Northern Virginia kept its main corps structure and commanders. However, many important generals were killed, badly wounded, or captured. For example, Lewis Armistead and William Barksdale were killed. John Bell Hood and Dorsey Pender were severely wounded.

Imboden's Wagon Train Journey

At 1 a.m. on July 4, Lee asked Brigadier General John D. Imboden to manage most of the army's trains. Imboden's 2,100 cavalrymen had not done much in the campaign until then. Lee and Stuart did not think highly of Imboden's group. But they were good for guard duty.

Lee gave Imboden's artillery battery five more batteries from his infantry. He also told Stuart to assign two cavalry brigades to protect the sides and back of Imboden's column. Imboden's orders were to leave Cashtown on the evening of July 4. He was to turn south at Greenwood, avoiding Chambersburg. Then he would take the direct road to Williamsport to cross the Potomac. After that, he would escort the train to Martinsburg. Finally, Imboden's group would return to Hagerstown to guard the retreat path for the rest of the army.

Imboden's train had hundreds of wagons. It stretched for 15–20 miles along the narrow roads. Getting these wagons ready, arranging their guards, loading supplies, and counting the wounded took until late afternoon on July 5. Imboden himself left Cashtown around 8 p.m. to join the front of his column.

The journey was very hard. Heavy rains started on July 4. Wounded men had to suffer the bad weather and rough roads in wagons without springs. Imboden's orders were not to stop until they reached their destination. This meant that broken-down wagons were left behind. Some very badly wounded men were also left on the roadsides. They hoped local people would find and help them.

The train was attacked during its march. At dawn on July 5, civilians in Greencastle attacked the train with axes. They tried to break the wagon wheels until they were chased away. That afternoon, at Cunningham's Cross Roads, Union cavalry attacked the column. They captured 134 wagons, 600 horses and mules, and 645 prisoners. About half of the prisoners were wounded. These losses made Stuart so angry that he asked for an investigation.

Fights at Fairfield and Monterey Pass

After dark on July 4, Hill's Third Corps started moving onto the Fairfield Road. James Longstreet's First Corps and Richard S. Ewell's Second Corps followed them. Lee went with Hill at the front of the column. He ordered Stuart to place two brigades to protect his left rear from Emmitsburg. By leaving in the dark, Lee got several hours' head start. The route from the west side of the battlefield to Williamsport was also about half as long as the routes the Union army could take.

Meade did not want to start chasing right away. He was not sure if Lee planned to attack again. His orders also said he had to protect Baltimore and Washington, D.C.. Meade thought the Confederates had strongly fortified the South Mountain passes. So, he decided to chase Lee on the east side of the mountains. He planned to march quickly to capture the passes west of Frederick, Maryland. This would threaten Lee's left side as he retreated.

However, Meade was wrong. Fairfield was only lightly guarded by two small cavalry brigades. The passes over South Mountain were not fortified. If Meade had captured Fairfield, Lee's army would have been forced to fight through Fairfield. This would have left their rear open to the Union army at Gettysburg. Or, they would have had to take their whole army through the Cashtown Pass, a much harder way to Hagerstown.

On July 3, while Pickett's Charge was happening, Union cavalry had a chance to stop Lee's retreat. Brigadier General Wesley Merritt's brigade left Emmitsburg. They were ordered to attack the Confederate right and rear. Merritt sent about 400 men to capture a Confederate supply train near Fairfield.

Before they reached the wagons, the 7th Virginia Cavalry stopped them. This started the small Battle of Fairfield. The U.S. cavalrymen fired from behind a fence, making the Virginians retreat. But then the 6th Virginia Cavalry charged and overwhelmed the Union soldiers. The Union lost 242 men, mostly prisoners. The Confederates lost 44 men. Even though it was a small fight, it meant the important Fairfield Road to the South Mountain passes stayed open for Lee.

Early on July 4, Meade sent his cavalry to attack the enemy's rear. He wanted them to "harass and annoy him as much as possible in his retreat." Eight of the nine cavalry brigades went out. Most of them moved south of Gettysburg. Brigadier General John Buford's division went directly from Westminster to Frederick. Merritt's division joined them on the night of July 5.

Late on July 4, Meade held a meeting with his commanders. They agreed the army should stay at Gettysburg until Lee moved. They also agreed the cavalry should chase Lee if he retreated. Meade decided to send a division from Major General John Sedgwick's VI Corps to check Lee's lines. This corps had seen the least fighting at Gettysburg. Meade wanted to find out what Lee planned to do. Meade ordered his chief of staff to prepare the army for a general move.

By the morning of July 5, Meade learned Lee had left. But he waited to order a full chase until he got the results of the scouting mission.

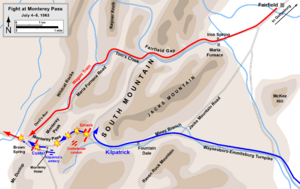

The Battle of Monterey Pass began on July 4. Brigadier General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick's cavalry division arrived near Fairfield just before dark. They easily pushed aside the Confederate guards. They met 20 men from the Confederate 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion. These men were guarding the road to Monterey Pass. With help from other cavalry and one cannon, the Marylanders held back 4,500 Union cavalrymen until after midnight.

Kilpatrick could not see in the dark. He felt his command was in "a perilous situation." He ordered Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer to charge the Confederates. Custer's 6th Michigan Cavalry broke through. This allowed Kilpatrick's men to reach and attack the wagon train. They captured or destroyed many wagons. They also took 1,360 prisoners, mostly wounded men in ambulances. They also captured many horses and mules.

After the fight at Monterey, Kilpatrick's division reached Smithsburg around 2 p.m. on July 5. Stuart arrived from over South Mountain with his brigades. A cannon fight between horse artillery units happened, damaging the small town. Kilpatrick pulled back at dark to save his prisoners and animals. He arrived at Boonsboro before midnight.

Meade's Cautious Pursuit

Sedgwick's corps started scouting before dawn on July 5. But instead of just one division, the whole corps went. They met the rear guard of Ewell's corps late in the afternoon near Fairfield. It was only a small fight. The Confederates camped a mile and a half west of Fairfield, holding their position with only their picket line.

Warren told Meade that he and Sedgwick thought Lee was gathering his main army around Fairfield. They believed Lee was getting ready for another battle. Meade immediately stopped his army. Early on July 6, he ordered Sedgwick to continue scouting to find out Lee's plans. Sedgwick argued with Meade. He said it was risky to send his whole corps into the rough country and thick fog ahead. By noon, Meade changed his plan. He went back to his original idea of advancing east of the mountains to Middletown, Maryland.

The delays in leaving Gettysburg and the confusing orders to Sedgwick caused Meade problems later. His opponents accused him of being slow and timid.

In view of Sedgwick's lack of aggressiveness in the advance to Fairfield his remark after the campaign that Meade in his pursuit "might have pushed Lee harder" seems singularly inappropriate.

Because of Meade's mixed signals, Sedgwick and Warren chose to be more careful. They waited until Ewell's Corps had completely left Fairfield. They stayed a safe distance behind Ewell's men as they moved west. Lee thought Sedgwick would attack his rear and was ready. He told Ewell, "If these people keep coming on, turn back and thresh them." Ewell replied, "By the blessing of Providence I will do it." He ordered his division to form a battle line. However, the VI Corps only followed Lee to the top of Monterey Pass. They did not chase him down the other side.

Chasing Lee to Williamsport

Other than Gettysburg, the Battle of Hagerstown was one of the bloodiest actions in the campaign. Each side reported losing more than 250 men. Most of these were rebel and Yankee horsemen, giving the lie to the infantrymen's derisive taunt, "Who ever heard of a dead cavalryman?"

Before Meade's main army started marching to chase Lee, Buford's cavalry division left Frederick. Their goal was to destroy Imboden's train before it could cross the Potomac. Hagerstown was a very important spot on the Confederate retreat path. Capturing it could block or delay their way to the river crossings.

On July 6, Kilpatrick's division, after its successful raid at Monterey Pass, moved towards Hagerstown. They pushed out two small Confederate brigades. However, Confederate infantry drove Kilpatrick's men back through the town streets. Stuart's remaining brigades arrived and were joined by two more brigades. Hagerstown was then recaptured by the Confederates.

Buford heard Kilpatrick's cannons nearby and asked for help on his right side. Kilpatrick decided to help Buford and join the attack on Imboden at Williamsport. Stuart's men put pressure on Kilpatrick's rear and right side from Hagerstown. Kilpatrick's men gave way, leaving Buford's rear open to attack. Buford stopped his effort when darkness fell. At 5 p.m. on July 7, Buford's men got within half a mile of the parked trains. But Imboden's command pushed back their attack.

The Battle of Boonsboro happened along the National Road on July 8. Stuart advanced from Funkstown and Williamsport with five brigades. He first met Union resistance at Beaver Creek Bridge, 4.5 miles north of Boonsboro. By 11 a.m., the Confederate cavalry had pushed forward into muddy fields. Fighting on horseback was almost impossible there. This forced Stuart's troopers and Kilpatrick's and Buford's divisions to fight on foot. By mid-afternoon, the Union left side, led by Kilpatrick, began to break. The Union soldiers were running low on ammunition under growing Confederate pressure. Stuart's advance ended around 7 p.m. when Union infantry arrived. Stuart then pulled back north to Funkstown.

Stuart's strong presence at Funkstown threatened any Union advance towards Williamsport. It put the Union army's right side and rear at serious risk if they moved west from Boonsboro. As Buford's division carefully approached Funkstown on July 10, it met Stuart's three-mile-long battle line. This started the [Second] Battle of Funkstown. (The first was a small fight on July 7.)

Colonel Thomas Devin's Union cavalry brigade attacked around 8 a.m. By mid-afternoon, Buford's cavalrymen were running low on ammunition and gaining little ground. Then, Colonel Lewis A. Grant's First Vermont Brigade of infantry arrived. They fought with a Confederate brigade. This was the first time opposing infantry had fought since the Battle of Gettysburg. By early evening, Buford's command started pulling back south towards Beaver Creek. There, the Union I, VI, and XI Corps had gathered.

Buford and Kilpatrick continued to hold their advanced position around Boonsboro. They waited for the Army of the Potomac to arrive. French's command sent troops to destroy the railroad bridge at Harpers Ferry. A brigade also took over Maryland Heights. This stopped the Confederates from going around the lower end of South Mountain and threatening Frederick from the southwest.

Standoff at the Potomac

Meade's infantry had been marching hard since the morning of July 7. Slocum's wing marched 29 miles on the first day. Parts of the XI Corps covered 30 to 34 miles. By July 9, most of the Army of the Potomac was gathered in a 5-mile line. Other Union forces were in place to protect the outer sides at Maryland Heights and Waynesboro.

Reaching these positions was hard because of heavy rains on July 7. The roads turned into deep mud. The III and V Corps had to take long detours. But the good thing was that these roads were closer to Frederick. Frederick was connected by railroad to Union supply centers. Also, these roads, including the paved National Road, were in better condition.

The spirit of the army is such that they will do most desperate fighting. ... The men know now that Lee's Army is not invincible and that the Army of the Potomac can win a victory if it is allowed to. Our Army ... ought to drive the Rebels into the Potomac.

The Confederate Army's rear guard arrived in Hagerstown on the morning of July 7. Their cavalry skillfully protected them. They began to set up defensive positions. By July 11, they held a 6-mile line on high ground. Their right side rested on the Potomac River near Downsville. Their left side was about 1.5 miles southwest of Hagerstown. This line covered the only road from Hagerstown to Williamsport. The Conococheague Creek protected their position from any attack from the west.

They built impressive earthworks. These had a 6-foot-wide wall on top and many places for cannons. This created areas where their cannons could fire across each other. Longstreet's Corps held the right side of the line, Hill's the center, and Ewell's the left. These defenses were finished on the morning of July 12. Just as the Union army arrived to face them.

Meade sent a telegram to his general-in-chief, Henry Halleck, on July 12. He said he planned to attack the next day, "unless something intervenes to prevent it." He again held a meeting with his commanders on the night of July 12. Of the seven senior officers, only Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth and Major General Oliver Otis Howard wanted to attack the Confederate defenses. The main objections were that they had not scouted the positions enough.

On July 13, Meade and Humphreys personally checked the positions. They gave orders to the corps commanders for a strong scouting mission on the morning of July 14. This one-day delay was another reason Meade's political enemies criticized him after the campaign. Halleck told Meade that it was "proverbial that councils of war never fight."

Crossing the Potomac

On the morning of July 13, Lee became frustrated waiting for Meade to attack him. He was also upset to see that the Union troops were digging their own trenches in front of his defenses. He said impatiently, "That is too long for me; I can not wait for that. ... They have but little courage!"

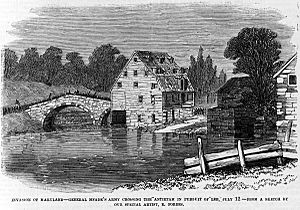

By this time, Confederate engineers had finished a new pontoon bridge over the Potomac. The river water had also gone down enough to be crossed by walking through it. Lee ordered a retreat to start after dark. Longstreet's and Hill's corps and the artillery would use the pontoon bridge at Falling Waters. Ewell's corps would cross the river at Williamsport by walking through the water.

Meade's orders said that the strong scouting mission by four of his corps would start by 7 a.m. on July 14. But by this time, it was clear the enemy had left. Union skirmishers (soldiers sent ahead to find the enemy) found that the trenches were empty. Meade ordered a general chase of the Confederates at 8:30 a.m. But it was too late to make much contact.

Cavalry led by Buford and Kilpatrick attacked the rear guard of Lee's army. This was Major General Henry Heth's division. They were still on a ridge about a mile and a half from Falling Waters. The first attack surprised the Confederates, who had had little sleep. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out. Kilpatrick attacked again, and Buford hit them on their right and rear. Heth's and Pender's divisions lost as many as 2,000 men as prisoners. Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew, who had survived Pickett's Charge with a minor hand wound, was mortally wounded at Falling Waters.

This small success against Heth did not make up for the great frustration in the Lincoln administration. They were angry that Lee had been allowed to escape. President Lincoln was quoted as saying, "We had them within our grasp. We had only to stretch forth our hands and they were ours. And nothing I could say or do could make the Army move."

Final Clashes in Virginia

Many descriptions of the Gettysburg Campaign end with Lee's crossing of the Potomac on July 13–14. However, the two armies did not settle into positions across from each other on the Rappahannock River for almost two more weeks. The official reports of the armies include the movements and small fights along the way.

On July 16, two Confederate cavalry brigades held the river crossings at Shepherdstown. They wanted to stop Union infantry from crossing. A Union cavalry division approached the crossings. The Confederates attacked them, but the Union cavalry held their position until dark before pulling back. Meade called this a "spirited contest."

The Army of the Potomac crossed the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry and Berlin (now Brunswick) on July 17–18. They advanced along the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains. They tried to get between Lee's army and Richmond.

On July 23, Meade ordered French's III Corps to cut off the retreating Confederate columns at Front Royal. They would do this by forcing their way through Manassas Gap. At dawn, French began his attack. The New York Excelsior Brigade, led by Brigadier General Francis B. Spinola, attacked a Confederate brigade defending the pass. The fight was slow at first. The larger Union force used its numbers to push the Confederates back through the gap. Around 4:30 p.m., a strong Union attack drove the Confederates further. But then they were reinforced by another division and artillery. By dusk, the Union attacks, which were not well coordinated, were stopped. During the night, Confederate forces pulled back into the Luray Valley. On July 24, the Union army occupied Front Royal. But Lee's army was safely out of reach.

What Happened Next

The retreat from Gettysburg marked the end of the Gettysburg Campaign. This was Robert E. Lee's last big attack in the Civil War. After this, all of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia's actions were in response to Union moves.

The Confederates lost over 5,000 men during the retreat. This included more than 1,000 captured at Monterey Pass. Another 1,000 stragglers (soldiers who fell behind) were captured from the wagon train. 500 were captured at Cunningham's Crossroads. 1,000 were captured at Falling Waters. Also, 460 cavalrymen and 300 infantry and artillery were killed, wounded, or missing during the ten days of small fights and battles.

The Union had over 1,000 casualties, mostly cavalrymen. This included 263 from Kilpatrick's division at Hagerstown and 120 from Buford's division at Williamsport. For the entire campaign, Confederate losses were about 27,000. Union losses were about 30,100.

Meade faced challenges during the retreat and chase. He was criticized for being too cautious. His army was also very tired. The march to Gettysburg was fast and exhausting. Then came the biggest battle of the war. Chasing Lee was physically demanding. It involved bad weather and difficult roads that were much longer than Lee's route. Soldiers left the army because their enlistment time ended. Also, the New York Draft Riots meant thousands of men who could have helped the Army of the Potomac were busy elsewhere.

Meade was heavily criticized for letting Lee escape. This was similar to what Major General George B. McClellan had done after the Battle of Antietam. Under pressure from Lincoln, Meade launched two campaigns in the fall of 1863. These were the Bristoe and Mine Run campaigns. Both tried to defeat Lee, but they failed. Meade also faced humiliation from his political enemies. They questioned his actions at Gettysburg and his failure to defeat Lee during the retreat.

Images for kids

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |