Robert Benchley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Benchley

|

|

|---|---|

Benchley photographed for Vanity Fair

|

|

| Born | Robert Charles Benchley September 15, 1889 Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | November 21, 1945 (aged 56) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer, critic, actor, film director |

| Genre | Deadpan, Parody, Surreal humour |

| Years active | 1910s-1945 |

| Spouse |

Gertrude Darling

(m. 1914) |

| Children | 2, including Nathaniel |

| Relatives | Peter Benchley and Nat Benchley (grandsons) |

Robert Charles Benchley (born September 15, 1889 – died November 21, 1945) was a famous American humorist. He was well-known for writing newspaper columns and acting in movies.

Benchley started his career at The Harvard Lampoon while studying at Harvard University. Later, he wrote many essays and articles for magazines like Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. He also made popular short films. His funny and unique style of humor made him respected and successful. He was admired by friends at the Algonquin Round Table in New York City and by people in the growing film industry.

He is especially remembered for his work with The New Yorker magazine. His essays, whether about current events or silly ideas, influenced many humor writers today. Benchley also became famous in Hollywood. His short movie How to Sleep was a big hit and won an award at the 1935 Academy Awards. He also acted in memorable movies like Alfred Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Nice Girl? (1941). Benchley even appeared as himself in Walt Disney's movie, The Reluctant Dragon (1941). His legacy includes his written works and many short movie appearances.

Contents

Life and Career

Growing Up

Robert Benchley was born on September 15, 1889, in Worcester, Massachusetts. He was the second son of Charles Henry Benchley and Maria Jane Moran. His older brother, Edmund, was thirteen years older than him. Robert was known for making up funny stories about himself, like saying he wrote A Tale of Two Cities before being buried in Westminster Abbey.

His father served in the army during the Civil War and in the Navy. After that, he settled in Worcester, got married, and worked as a town clerk. Robert's grandfather, Henry Wetherby Benchley, was a politician in Massachusetts. He went to Houston, Texas, and helped the Underground Railroad, a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. He was even arrested for it.

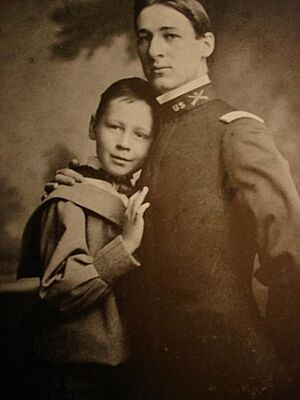

Brother Edmund's Death

Robert's older brother, Edmund (born March 3, 1876), was a student at West Point in 1898. His class graduated early to help prepare for the Spanish–American War. Sadly, Edmund was killed on July 1 at the Battle of San Juan Hill.

Edmund's fiancée, Lillian Duryea, was a wealthy woman who cared a lot for Robert for many years. Edmund's death might have made Robert feel strongly about peace, which showed up in his writing. Also, because the news about Edmund arrived during a July 4th celebration, Robert always connected fireworks with his brother's death.

Meeting His Wife

Robert Benchley met Gertrude Darling when they were in high school in Worcester. They got engaged during his last year at Harvard University and married in June 1914. Their first child, Nathaniel Benchley, was born a year later. Their second son, Robert Benchley Jr., was born in 1919.

Education and College Years

Robert went to South High School in Worcester. He was active in school plays and academic events. Thanks to financial help from his late brother's fiancée, Lillian Duryea, he could attend Phillips Exeter Academy for his final year of high school. Benchley loved the school and stayed involved in creative activities, even if it sometimes affected his grades.

Benchley started at Harvard University in 1908, again with Lillian Duryea's help. He joined the Delta Upsilon fraternity in his first year. He enjoyed the friendships there and still did well in his classes, especially English and government. His humor started to shine during this time. Benchley often entertained his fraternity brothers with impressions of classmates and professors, which made him quite popular.

During his first two years at Harvard, Benchley worked for the student publications Harvard Advocate and the Harvard Lampoon. He was chosen for the Lampoon's board of directors in his third year. This was unusual because he was the art editor, and these positions usually went to the best writers. Being on the Lampoon board opened other doors for Benchley. He was nominated to the Signet Society club and became the only college student member of the Boston Papyrus Club at that time.

Besides his work at the Lampoon, Benchley acted in several plays, including Hasty Pudding shows like The Crystal Gazer and Below Zero. He thought about a career after college. An English professor, Charles Townsend Copeland, suggested he become a writer. Benchley and his friend Gluyas Williams from the Lampoon thought about writing and illustrating theater reviews as freelancers. Another professor suggested he talk to the Curtis Publishing Company. Benchley didn't like that idea at first and took a job at a government office in Philadelphia. He didn't get his degree from Harvard until 1913 because he missed a credit due to illness. He fixed this by writing a funny paper about the U.S.-Canadian Fisheries Dispute from the point of view of a cod fish. He started working at Curtis after getting his diploma.

Early Career

Benchley did writing work for the Curtis Company after graduation. He also had other small jobs, like translating French catalogs for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In September, he was hired full-time by Curtis to write for their new internal magazine, Obiter Dicta. The first issue was not liked by the bosses, who thought it was "too technical" and "lacked punch." Things didn't get better for Benchley, and a failed joke at a company dinner made things worse. He tried to write in his own style, but it wasn't a good fit, and he eventually quit.

Benchley had several similar jobs over the next few years. He started public speaking again after a Harvard–Yale football game in 1914. He played a joke where a "Professor Soong" answered football questions in Chinese, and Benchley "translated." This prank, called "the Chinese professor caper" by the local news, made him more famous. Benchley continued to freelance, selling his first piece to Vanity Fair in 1914. It was called "Hints on Writing a Book," a funny take on popular non-fiction articles. His work for Vanity Fair was not steady, so he took a job with the New York Tribune.

Benchley started as a reporter at the Tribune. He wasn't very good at getting quotes, but he had more success covering lectures. He was promised a job with the Tribune's Sunday magazine when it started. He soon became the chief writer there. He wrote two articles a week: one reviewing non-fiction books and another feature article about anything he wanted. This freedom made his writing better, and his success in the magazine led his editors to give him his own signed column in the main Tribune newspaper.

In early 1916, Benchley filled in for P. G. Wodehouse at Vanity Fair, reviewing theater in New York. This inspired the Tribune magazine staff to be more creative. However, Benchley, who believed in peace, became unhappy with the Tribune's strong opinions about World War I. In 1917, the Tribune closed the magazine, and Benchley was jobless again. He decided to continue freelancing, as he had made a name for himself at Vanity Fair.

This freelancing period was tough at first. Benchley sold only one piece to Vanity Fair and got many rejections in two months. When he was offered a job as a press agent for Broadway producer William A. Brady, he took it, even though his friends advised against it. This job was not good because Brady was very difficult to work for. Benchley quit to become a publicity director for the government's Aircraft Board in early 1918. This experience wasn't much better. When he was offered a chance to return to the Tribune with new editors, Benchley accepted.

At the Tribune, Benchley and new editor Ernest Gruening were in charge of a twelve-page picture supplement called the Tribune Graphic. They had a lot of freedom, but Benchley's war coverage and focus on African-American soldiers made management suspicious. They were accused of being pro-German. Benchley resigned, saying there was no proof against Dr. Gruening and that management was trying to ruin the career of the first person in three years who made the Tribune look like a good newspaper.

Benchley had to take a publicity job with the Liberty Loan program. He kept freelancing until Collier's magazine offered him an associate editor job. Benchley told Vanity Fair about this offer, hoping they would match it, as he liked Vanity Fair more. Vanity Fair then offered him the job of managing editor, which he accepted in 1919.

A big influence on Benchley's early career was the friendship of Dr. Stephen Leacock, a Canadian economist and humorist. Leacock admired Benchley's humor and they started writing to each other. Leacock encouraged Benchley to put his columns into a book. In 1921, Of All Things was published, and Leacock wrote the introduction for the British edition. Benchley later said he read everything Leacock ever wrote.

Vanity Fair and Beyond

Benchley started at Vanity Fair with his friends Robert Emmet Sherwood and Dorothy Parker. Parker had taken over theater criticism from P. G. Wodehouse earlier. The style of Vanity Fair suited Benchley well, allowing his columns to be humorous, often as parodies. Benchley's work was usually published twice a month. Some of his columns, featuring a character he created, were under the name Brighton Perry, but he took credit for most of them. Sherwood, Parker, and Benchley became good friends, often having long lunches at the Algonquin Hotel.

When the editors went to Europe, the three friends took advantage of it. They wrote articles making fun of local theater and giving funny comments on various topics, like how Canadian ice hockey affected fashion in the United States. This worried Sherwood, as he thought it could risk his upcoming pay raise.

Things got worse at Vanity Fair when the editors returned. They sent a memo saying staff couldn't talk about salaries to control them. Benchley, Parker, and Sherwood responded with their own memo. Then, they wore signs around their necks showing their exact salaries for everyone to see. Management tried to give "tardy slips" to staff who were late. On one of these, Benchley wrote a very tiny, detailed excuse about a herd of elephants on 44th Street. These problems led to low spirits in the office. It ended with Parker being fired, supposedly because play producers complained about her theater reviews. When Benchley heard she was fired, he resigned. This was mentioned in Time magazine by Alexander Woollcott. Parker called it "the greatest act of friendship I'd ever seen" because Benchley had two children at the time.

After Benchley resigned, he received many freelance job offers. He worked constantly, even though he claimed to be very lazy. He was offered $200 per article for The Home Sector. He also got a weekly freelance salary from New York World to write a book review column three times a week for the same pay he got at Vanity Fair. The column, called "Books and Other Things," lasted for one year. It included everyday topics like Bricklaying In Modern Practice. However, Benchley's writing a column for David Lawrence made his World bosses angry, and "Books and Other Things" was stopped.

Benchley continued to freelance, sending humor columns to various magazines, including Life. Fellow humorist James Thurber said Benchley's columns were the only reason people read the magazine. He kept meeting his friends at the Algonquin Hotel, and the group became known as the Algonquin Round Table. In April 1920, Benchley got a job with Life writing theater reviews. He did this regularly until 1929, eventually taking full control of the drama section. His reviews were known for their style, and he often used them to talk about issues important to him, whether small (people who cough during plays) or more serious (like unfair treatment of people based on race).

Things changed for Benchley a few years later. The members of the Round Table put together a play. This was a response to a challenge from actor J. M. Kerrigan, who was tired of their complaints about the theater season. The show, called No Sirree!, played for one night on April 30, 1922, at the 49th Street Theatre. It was "An Anonymous Entertainment by the Vicious Circle of the Hotel Algonquin." Benchley's part in the show, "The Treasurer's Report," featured him as a nervous, disorganized man trying to explain an organization's yearly costs. The show was praised by both the audience and other actors, and Benchley's performance got the biggest laughs.

People often asked for "The Treasurer's Report" to be performed again. Irving Berlin (who was the music director for No Sirree!) encouraged producer Sam H. Harris to ask Benchley to perform it in Berlin's Music Box Revue. Benchley didn't want to be a regular performer on stage. He decided to ask Harris for a very high amount of money, $500 a week, for his short act, hoping Harris would say no. But Harris replied, "OK, Bob. But for $500 you better be good," which completely surprised Benchley. The Music Box Revue started in September 1921 and ran until September 1922. Benchley performed his eleven-minute skit eight times a week.

Movies and The New Yorker

Benchley kept getting good responses from his performances. In 1925, he accepted an offer from movie producer Jesse L. Lasky to write screenplays for six weeks at $500. This didn't lead to many big results, but Benchley did get credit for writing the title cards for the Raymond Griffith silent movie You'd Be Surprised (released September 1926). He was also asked to write titles for two other movies.

Benchley was also hired to help with the script for a George Gershwin musical called Smarty, starring Fred Astaire. Benchley's name was listed as a writer on the sheet music during the tryout period. This experience wasn't as good, as most of Benchley's work was cut out. The final show, Funny Face, did not include Benchley's name.

Feeling tired, Benchley started his next project: a movie version of his piece The Treasurer's Report. It was filmed in 1928 by Fox using their new Movietone sound system. The filming was quick. Even though he thought he didn't perform well, the short film was a financial and critical success. This was especially true because talking short comedies were new, and Benchley's early efforts helped create them. Benchley also appeared in another short film not written by him, The Spellbinder. As Life magazine said after he left in 1929, "Mr. Benchley has left Dramatic Criticism for the Talking Movies."

While filming various short movies, Benchley also started working at The New Yorker magazine. It began in February 1925, run by Benchley's friend Harold Ross. Benchley and many of his Algonquin friends were careful about getting involved with another publication. However, he did some freelance work for The New Yorker in its early years. Later, he was invited to be a newspaper critic. Benchley first wrote the column using the name Guy Fawkes, and the column was well-liked. Benchley wrote about everything from careless reporting to political issues in Europe, and the magazine grew. He was invited to be the theater critic for The New Yorker in 1929, quitting Life. Contributions from Woollcott and Parker became regular features. The New Yorker published about forty-eight Benchley columns each year in the early 1930s.

With The New Yorker becoming popular, Benchley was able to stay away from Hollywood for a few years. In 1931, he was convinced to do voice work for RKO Radio Pictures for a movie called Sky Devils. He also acted in his first feature movie, The Sport Parade (1932) with Joel McCrea. Working on The Sport Parade made Benchley miss the autumn theater openings, which embarrassed him. However, the appeal of moviemaking didn't go away. RKO offered him a writing and acting contract for the next year for more money than he was making at The New Yorker.

Benchley on Film and "How to Sleep"

Benchley returned to Hollywood during the Great Depression and when talking movies were becoming very popular. He quickly got involved in many productions. While Benchley was more interested in writing than acting, one of his important acting roles was as a salesman in Rafter Romance. His work caught the attention of MGM. Benchley took a role in the feature movie Dancing Lady (1933), which also starred Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Fred Astaire, Nelson Eddy, and the Three Stooges. That same year, Benchley appeared in the short movies Your Technocracy and Mine for Universal Pictures and How to Break 90 at Croquet for RKO. He continued to work in Hollywood as a writer and performer. He helped write dialogue for the mystery Murder on a Honeymoon (1935) and appeared in the big production China Seas for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. This movie starred Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Wallace Beery, and Rosalind Russell.

After China Seas was finished, MGM asked Benchley to write and perform in a short film. It was inspired by a study on sleep done by the Mellon Institute for the Simmons Mattress Company. The movie, How to Sleep, was filmed in two days. Benchley was both the narrator and the person sleeping. He said the sleeping part was "not much of a strain, as [he] was in bed most of the time." Benchley was actually a last-minute choice for the film. His son Nathaniel Benchley remembered that How to Sleep was supposed to be a Pete Smith short, but Pete Smith was sick. They tried to get someone else, but they couldn't make it. Finally, they asked his father if he would try to do it. The film was well-received at early showings and was promoted heavily. A picture from the film was even used in Simmons advertisements. The only group not happy was the Mellon Institute, who didn't like the studio making fun of their study.

How to Sleep won the award for Best Short Subject at the 1935 Academy Awards. MGM then started a whole series of 10-minute comedy films. These showed Benchley giving funny instructional lectures (like How to Be a Detective, How to Rest) or dealing with everyday problems (like An Evening Alone, Home Movies).

While starring in his short films, Benchley also returned to feature films. He was in the musical Broadway Melody of 1938 and had his biggest role yet in the comedy Live, Love and Learn. This film is also known for its funny trailer, "The Glamorous Robert Benchley in How to Make a Movie Trailer." It was made like one of his comedy shorts and even used their theme song.

Benchley's 1937 short film A Night at the Movies was his biggest success since How to Sleep. It showed Mr. B.'s terrible evening at the local movie theater. It was nominated for an Oscar and got him a contract for more short films. These films were made faster than his earlier ones (How to Sleep took two days, but How to Vote took less than twelve hours). This took a toll on Benchley. He still completed two shoots in one day, but he rested for a while after the 1937 schedule.

Benchley's return led to two more short films. His high profile led to talks about sponsoring a Benchley radio program and many appearances on television shows. This included the first television entertainment program ever broadcast, an untitled test program using an experimental antenna on the Empire State Building. The radio program, Melody and Madness, featured music by Artie Shaw. It was a showcase for Benchley's acting, as he didn't write it. It was not well-received and was removed from the schedule. However, television was still new, and few people saw the program, so it didn't hurt Benchley's reputation much.

Later Life and Death

The year 1939 was not good for Benchley's career. His radio show was canceled, and MGM decided not to renew his short films contract. The New Yorker magazine was frustrated that Benchley's film career was taking over his theater column, so they appointed Wolcott Gibbs to take his place. After his last New Yorker column in 1940, Benchley signed with Paramount Pictures for a new series of one-reel short films. These were all filmed at Paramount's studio in Astoria, New York. Most of them were based on his old essays. The Witness was based on his 1935 essay "Take the Witness!", where Benchley imagined winning a tough cross-examination. Crime Control was from his 1931 story "The Real Public Enemies," showing how everyday household objects can seem sneaky.

In 1940, Benchley appeared in Alfred Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent. He also helped write some of the dialogue for it. In 1941, Benchley got more roles in full-length movies. These included Walt Disney's The Reluctant Dragon, where Benchley tours the Disney studio. He was also in Nice Girl? with Deanna Durbin, which was special because Benchley gave a rare serious performance. He also made two films for Columbia Pictures: Bedtime Story starring Fredric March and Loretta Young, and the comedy Three Girls About Town, starring Joan Blondell.

Benchley mostly worked as a freelance actor because his Paramount shorts contract didn't pay as much as feature films. He was cast in smaller roles for various romantic comedies. He appeared in important roles with Fred Astaire in You'll Never Get Rich (1941) and The Sky's the Limit (1943). Paramount did not renew his shorts contract when it ended in 1942. This wasn't Benchley's fault; the studio was stopping all short film production in New York.

Benchley signed an exclusive contract with MGM to work in Hollywood. This situation wasn't good for Benchley. The studio "mishandled" him and kept him too busy to do his own writing. His contract ended with only four short films completed, and he couldn't sign another contract. After two books of his old New Yorker columns were printed, Benchley stopped writing for good in 1943. He signed one more contract with Paramount for feature films in December of that year.

While Benchley's books and Paramount contract gave him financial security, he was still unhappy with how his career had changed. By 1944, he was taking small, unrewarding roles in the studio's less important films, like the musical National Barn Dance. He also appeared as a guest on radio shows.

By this time, Robert Benchley was known on screen as a funny lecturer who tried but failed to explain any topic. In this role, Paramount cast him in the 1945 Bob Hope-Bing Crosby comedy Road to Utopia. Benchley would interrupt the movie to "explain" the silly story. He also made guest appearances on popular radio shows. His last radio appearance was on October 30, 1945.

Benchley died in a New York hospital on November 21, 1945. His funeral was private, and he was buried in a family plot in Prospect Hill Cemetery on the island of Nantucket.

In 1954, The Benchley Roundup was published. It was a collection of Robert Benchley's favorite essays, edited by his son Nathaniel. This led MGM to re-release Benchley's movie shorts to theaters in 1955.

In 1960, Benchley was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for motion pictures at 1724 Vine Street.

Family Life

Nathaniel Benchley, Robert's son, also became an author. He published a book about his father in 1955. Nathaniel was also a respected writer of fiction and children's books. Nathaniel married and had sons who also became writers. Peter Benchley is best known for the book Jaws, which was made into the famous movie of the same name. Nat Benchley wrote and performed a popular one-man show based on his grandfather Robert's life.

Algonquin Round Table

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of writers and actors in New York City. They met regularly between 1919 and 1929 at the Algonquin Hotel. It started with Benchley, Dorothy Parker, and Alexander Woollcott when they worked at Vanity Fair. The group grew to include more than a dozen regular members of the New York media and entertainment world. These included playwrights George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly, and journalist/critic Heywood Broun. The group became famous because of the attention they received and their contributions to their fields.

Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle is a 1994 American film that shows the Round Table from Dorothy Parker's point of view. Campbell Scott plays Robert Benchley in the movie.

Humor Style

Benchley's humor developed during his time at Harvard. He was already known for his speaking skills, but his style truly formed while working at the Lampoon. At that time, there were two main types of humor. One was "crackerbarrel," which used dialects and disliked formal education, like humorists Artemus Ward and David Ross Locke. The other was a more "genteel" style, which was very literary and upper-class, made popular by Oliver Wendell Holmes. These two styles, though different, appeared together in magazines like Vanity Fair and Life. The Lampoon mostly used the genteel style, which suited Benchley. While some of his writings could fit the crackerbarrel style, Benchley's use of puns and wordplay was more like the literary humorists. This is shown by his success with The New Yorker, known for its readers' sophisticated tastes.

Benchley's simple definition of humor was: "Anything that makes people laugh."

Benchley's characters were usually exaggerated versions of the average person. They were designed to show a difference between the character and everyone else. The character was often confused by society and acted "differently." For example, the character in How to Watch Football thinks it makes sense for a fan to skip the live game and just read about it in the newspaper. This character, called the "Little Man," was based on Benchley himself. This character didn't appear in Benchley's writing much after the early 1930s, but it lived on in his speaking and acting roles. This character was clear in Benchley's speech at his Harvard graduation and appeared throughout his career, like in "The Treasurer's Report" in the 1920s and his work in feature films in the 1930s.

His funny articles about current events written for Vanity Fair during the war still kept their lightheartedness. He wasn't afraid to make fun of important people or institutions. One piece he wrote was called "Have You a Little German Agent in Your Home?" His observations about the average person often turned into angry rants, like his piece "The Average Voter." In this piece, the voter "Forgets what the paper said...so votes straight Republicrat ticket." His lighter works still touched on current issues, comparing a football game to patriotism, or chewing gum to diplomacy and money matters with Mexico.

In his films, the exaggerated common man continued. Much of his time in movies was spent making fun of himself. The longer, story-driven short films, like Lesson Number One, Furnace Trouble, and Stewed, Fried and Boiled, also show a Benchley character who is overwhelmed by seemingly simple tasks. Even his more typical characters had these qualities, like the clumsy sportscaster Benchley played in The Sport Parade.

Benchley's humor inspired many later humorists and filmmakers. Dave Barry, a writer and humor columnist, has called Benchley his "idol" and said he "always wanted to write like [Benchley]." Horace Digby claimed that Benchley influenced his early writing style more than anyone else. Filmmaker Sidney N. Laverents also lists Benchley as an influence. James Thurber used Benchley as a reference, noting Benchley's skill at showing "the commonplace as remarkable" in "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty". In 1944, Benchley starred as Mitty in a radio version of the story for the series This Is My Best.

Works

Benchley wrote over 600 essays, which were first put together in twelve books. He also appeared in many films, including 48 short films that he mostly wrote or co-wrote, and numerous feature films.

After his death, Benchley's works continued to be released in books. These include the 1983 Random House collection The Best of Robert Benchley, and the 2005 collection of short films Robert Benchley and the Knights of the Algonquin. This collection brought together many of Benchley's popular short films from his years at Paramount with other works from fellow humorists and writers Alexander Woollcott and Donald Ogden Stewart.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Robert Benchley para niños

In Spanish: Robert Benchley para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |