Texas annexation facts for kids

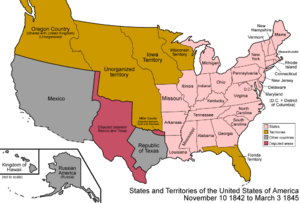

The Texas annexation was when the Republic of Texas joined the United States in 1845. Texas became the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

Texas had declared independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836. It asked to join the U.S. that same year, but the U.S. said no. Most people in Texas, called Texians, wanted to join the U.S.

At the time, leaders of the main U.S. political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, were against Texas joining. Texas was a large area where slavery was allowed. Bringing it in would cause more arguments between states that allowed slavery and those that didn't. Also, the U.S. wanted to avoid a war with Mexico. Mexico had made slavery illegal and didn't agree that Texas was independent.

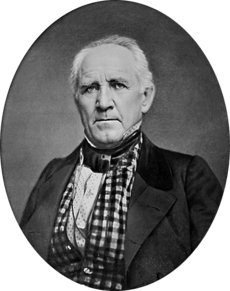

By the early 1840s, Texas was having money problems. So, Sam Houston, the President of Texas, started talking with Mexico. He hoped to get Mexico to officially recognize Texas's independence. The United Kingdom helped with these talks.

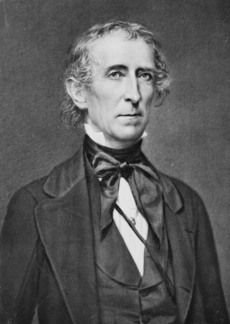

In 1843, U.S. President John Tyler, who didn't belong to a political party, decided to try and annex Texas. He hoped this would help him get re-elected. He also worried that the British government might try to end slavery in Texas, which would affect slavery in the U.S.

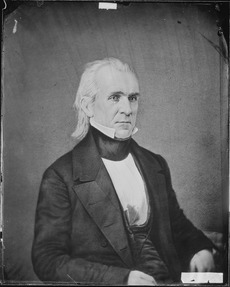

Tyler secretly talked with the Texas government. In April 1844, they agreed on a treaty for annexation. When the details became public, the idea of Texas joining the U.S. became a big topic in the 1844 presidential election. Democrats who wanted Texas to join stopped their leader, Martin Van Buren, from being nominated. Instead, they chose James K. Polk, who supported adding Texas and believed in Manifest Destiny.

In June 1844, the U.S. Senate, mostly Whigs, strongly rejected the Tyler-Texas treaty. But Polk, who supported annexation, narrowly won the 1844 election against Henry Clay, who was against it.

In December 1844, President Tyler, who was leaving office soon, asked Congress to pass his treaty with a simple majority vote. The House of Representatives, mostly Democrats, agreed. They passed a bill that added more rules to help slavery in Texas. The Senate barely passed a compromise version of the House bill. This bill gave the new President, Polk, two choices: either annex Texas right away or start new talks to change the annexation terms.

On March 1, 1845, President Tyler signed the annexation bill. On March 3, his last full day in office, he sent the House version to Texas, offering immediate annexation. When Polk became president the next day, he encouraged Texas to accept Tyler's offer. Texas agreed, and its people approved the plan. President Polk signed the bill on December 29, 1845, making Texas the 28th state. Texas officially joined the U.S. on February 19, 1846.

After Texas joined, the relationship between the U.S. and Mexico got worse. They argued over the border between Texas and Mexico. Just a few months later, the Mexican–American War began.

Contents

Texas Joins the U.S.

Early Expansion and Texas

Spain first mapped Texas in 1519. It was part of the huge Spanish empire for over 300 years. When the U.S. bought the Louisiana territory from France in 1803, many Americans thought it included parts of Texas.

The border between the U.S. and Spain near Texas was set in 1819. This was done through talks between U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and the Spanish ambassador. The Florida Treaty of 1819 gave up any U.S. claims to Texas. But Americans who wanted the U.S. to expand still wanted Texas.

The debate over slavery grew stronger around 1819-1821 with the Missouri Compromise. This agreement set a line (the 36°30' parallel) in the Louisiana Purchase lands. North of the line, slavery was not allowed. South of it, slavery was allowed. Some Southern leaders felt that if slavery was limited in the north, they would need Texas for more land where slavery could exist.

When Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, the U.S. did not challenge Mexico's claim to Texas. Both Presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson tried to buy Texas from Mexico, but they were not successful.

Settling Texas and Its Independence

In the late 1600s, Spanish and Native people began settling Texas. The Spanish built missions and forts, like the San Antonio Missions. The city of San Antonio was founded in 1718.

In the early 1820s, Anglo-American immigrants, mostly from the Southern United States, moved to Mexican Texas. Mexico invited them to settle the empty lands and grow cotton. Stephen F. Austin helped manage these settlers. About 20% of these settlers were enslaved people. Mexican authorities generally let the settlers manage themselves, even allowing slavery by calling it "permanent indentured servitude."

However, Mexican laws were often ignored by the American settlers. For example, laws against slavery and forced labor were not followed. Also, settlers were supposed to be Catholic, but many were not. Mexico realized it was losing control. After the Fredonian Rebellion in 1826, Mexico changed its policy. In 1829-1830, Mexico outlawed slavery and stopped more American immigration to Texas. Mexican soldiers were sent to Texas, which led to small uprisings and a civil war.

Texans declared independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836. On April 20-21, Texas forces led by General Sam Houston defeated the Mexican army at the Battle of San Jacinto. Mexican General Santa Anna was captured and signed an agreement for Texas independence. But the Mexican government refused to accept it. Texas was now independent, but its future was uncertain because Mexico still didn't recognize it.

After independence, fewer white settlers and enslaved black people moved to Texas. This was because Texas's status was unclear, and there was a threat of more war with Mexico. People felt safer in the U.S. Also, the price of cotton, Texas's main export, dropped in the 1840s. This led to fewer workers, less tax money, large debts, and a weaker Texas army.

Presidents Jackson and Van Buren

Most American immigrants in Texas wanted to join the U.S. right away. But President Andrew Jackson waited until his last day in office to recognize Texas's independence. He wanted to avoid the issue during the 1836 election. Jackson was careful because Northern states worried that Texas would become several new slave states, upsetting the balance of power in Congress.

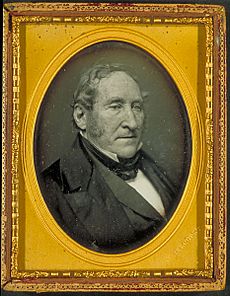

Jackson's successor, President Martin Van Buren, thought annexing Texas would cause big political problems, especially if it led to war with Mexico. In August 1837, Texas formally asked to join, but Van Buren quickly said no. Attempts to pass annexation laws in Congress failed. After the 1838 election, the new Texas president, Mirabeau B. Lamar, withdrew Texas's offer to join the U.S. Texas was stuck until John Tyler became president in 1841.

President Tyler's Efforts

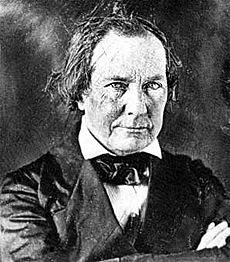

William Henry Harrison, a Whig, won the 1840 election. But he died soon after becoming president, and Vice-President John Tyler took over. The Whig party kicked Tyler out in 1841 because he kept rejecting their financial laws. Tyler, now without a party, focused on foreign affairs to save his presidency. He sided with Southern politicians who wanted to expand slavery.

In June 1841, Tyler said he wanted to expand the country. He believed this would keep the balance between states and the national government and protect American ways, including slavery. Tyler's advisors told him that getting Texas would help him win a second term. It became his main goal. Tyler worked with his Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, on other important diplomatic issues first.

After the Webster–Ashburton Treaty was approved in 1843, Tyler made Texas annexation his top priority. He had a supporter, Representative Thomas Walker Gilmer, write a public letter. This letter said that Texas would solve problems between the North and South and help the economy. It also said that states should decide on slavery themselves. Tyler argued that annexing Texas would bring peace and security to the U.S. If Texas stayed independent, it could be a danger. Tyler then got his anti-annexation Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, to resign. On June 23, 1843, he appointed Abel P. Upshur, a strong supporter of Texas annexation. This showed Tyler was serious about getting Texas.

Tyler's Campaign for Texas

In late 1843, Secretary Upshur sent a letter to the U.S. Minister in Great Britain. He complained about Britain's efforts to end slavery around the world. He warned that Britain interfering in Texas would be like interfering with U.S. institutions. Upshur leaked this letter to the press to make Americans angry at Britain.

In spring 1843, Tyler's agent, Duff Green, went to Europe. He was supposed to gather information and talk about the Oregon territory. He also worked to stop European powers from stopping the slave trade at sea. Green told Upshur in July 1843 that he found a "loan plot." He claimed American abolitionists and the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Aberdeen, planned to give money to Texas if Texas freed its enslaved people.

Minister Everett investigated these claims but found that Britain wasn't very interested in abolitionist plots in Texas. However, Green's reports worried Tyler. When Tyler heard that Lord Aberdeen had encouraged talks between Mexico and Texas, possibly to get Texas to free its enslaved people, Tyler acted fast. On September 18, 1843, he ordered secret talks with Texas Minister Isaac Van Zandt to negotiate annexation. Talks began on October 16, 1843.

Texas, Mexico, and British Talks

By summer 1843, Texas President Sam Houston was talking with Mexico again. They were considering a deal where Texas might govern itself as part of Mexico, with Britain helping. Texas leaders felt Tyler's government wasn't doing enough to annex Texas. Also, the 1844 U.S. election was coming, and both major parties were against Texas joining.

Texas and Mexico considered options like Texas being an independent republic that would free its enslaved people. Van Zandt, the Texas Minister, wanted annexation but wasn't allowed to talk about it with the U.S. Texas was more worried about avoiding war with Mexico than British interference with slavery.

Still, U.S. Secretary of State Upshur pushed Texas to start annexation talks. In January 1844, he told President Houston that the U.S. political mood had changed. He said enough Senators would vote for a Texas treaty.

Texans were hesitant to sign a treaty without a written promise of military help from the U.S. They feared Mexico would attack if the talks became public. If the U.S. Senate didn't approve the treaty, Texas would face Mexico alone. The Tyler government couldn't promise military help because only Congress could declare war. But Upshur gave a verbal promise of defense. So, President Houston, urged by the Texas Congress, agreed to reopen annexation talks.

U.S.-Texas Treaty Talks

As Secretary Upshur sped up the secret treaty talks, Mexican diplomats found out. The Mexican minister to the U.S. warned Upshur that if the U.S. approved the treaty, Mexico would cut ties and declare war. Upshur ignored the warnings and continued. He also secretly lobbied U.S. Senators, arguing that Texas would help national security and peace. By early 1844, Upshur believed 40 of 52 Senators would approve the treaty, more than the two-thirds needed. Tyler kept the talks secret in his December 1843 speech to Congress to avoid upsetting Texas.

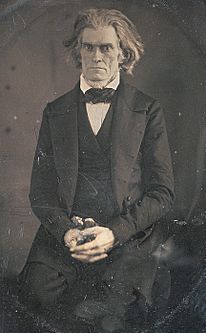

The Tyler-Texas treaty was almost finished when Upshur and Secretary of the Navy Thomas W. Gilmer died in an accident on the USS Princeton on February 28, 1844. This was a big setback because Tyler expected Upshur to get Senate support. Tyler chose John C. Calhoun to replace Upshur and finish the treaty. Calhoun was a strong supporter of slavery and annexation, but also controversial.

Robert J. Walker's "Safety-Valve" Idea

As the secret talks ended, Senator Robert J. Walker of Mississippi, a Tyler ally, wrote a widely read letter. It argued for immediate annexation. Walker said Texas could be acquired in many ways, all constitutional. He also said that Texas was important for slavery and race. He imagined Texas as a place where both free and enslaved African Americans could move south. Eventually, this would provide labor for Central America and empty the U.S. of its enslaved population.

This "safety-valve" idea appealed to white Northerners who worried about what would happen if slavery ended in the South. It was similar to ideas of sending black people overseas. Walker also warned that if annexation failed, Britain might get Texas to free its enslaved people. This would destabilize slave states in the Southwest. He called abolitionists traitors working with the British.

This idea also played on economic fears. The price of cotton was low. Walker's "escape route" promised to increase demand for enslaved people in Texas's cotton fields, raising their value. Plantation owners in the older Southern states could sell their extra enslaved people for profit. Walker wrote that Texas annexation would solve these problems and "fortify the whole Union."

Walker's letter led to strong demands for Texas from pro-slavery expansionists in the South. In the North, it allowed some to support Texas without seeming to support slavery extremists. His ideas greatly influenced the annexation debates.

Tyler-Texas Treaty and the 1844 Election

| Treaty of annexation concluded between the United States of America and the Republic of Texas | |

|---|---|

| Drafted | February 27, 1844 |

| Signed | April 12, 1844 |

| Location | Washington |

| Effective | Not ratified |

| Signatories | |

| Consent refused by the U.S. Senate (Senate Journal, June 8, 1844, volume 430, pp. 436–438). | |

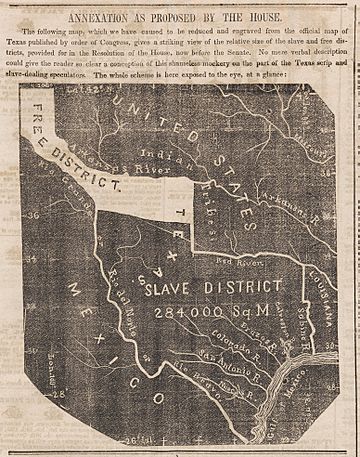

The Tyler-Texas treaty, signed on April 12, 1844, aimed to bring Texas into the U.S. as a territory. Texas would give its public lands to the U.S., and the U.S. government would take on Texas's debt, up to $10 million. The treaty didn't specify Texas's exact borders. It also allowed for four new states to be created from Texas, with three likely to be slave states. The treaty avoided mentioning slavery directly but protected "all [Texas] property as secured in our domestic institutions" (meaning slavery).

After signing the treaty, Tyler sent troops to Louisiana and warships to the Gulf of Mexico to protect Texas. If the Senate didn't pass the treaty, Tyler promised to ask Congress to make Texas a state. Tyler's cabinet was divided. The Secretary of War praised the annexation terms. But the Secretary of the Treasury was worried about Tyler using military force without Congress's approval. He resigned.

Tyler sent his treaty to the Senate on April 22, 1844. Two-thirds of the Senate needed to approve it. Secretary of State Calhoun, who started his job on March 29, 1844, sent a letter to the British minister. He criticized Britain's anti-slavery actions in Texas. He included this "Packenham Letter" with the treaty. Calhoun wanted to create a sense of crisis among Southern Democrats. In the letter, he called slavery a "social blessing" and said getting Texas was necessary to protect slavery in the U.S. Tyler and Calhoun hoped to unite the South and force the North to choose: support Texas annexation or risk losing the South.

Tyler and Polk's Nomination

President Tyler expected the treaty to be debated secretly. But less than a week later, the treaty and Calhoun's letter were leaked to the public. This caused a national outcry because it seemed the only reason for annexing Texas was to protect slavery. Anti-annexation groups in the North grew stronger, making both major parties more against Tyler's plan. The main presidential candidates, Democrat Martin Van Buren and Whig Henry Clay, publicly spoke out against the treaty. Texas annexation and taking over the Oregon territory became the main issues in the 1844 election.

Tyler, already out of the Whig party, tried to form a new party. He hoped to make Democrats support his expansionist ideas. If he ran as a third-party candidate, he could take votes from pro-annexation Democrats, which would help Henry Clay win. But pro-annexation Southern Democrats, with help from some Northern Democrats, stopped Martin Van Buren from being nominated. Instead, they chose James K. Polk of Tennessee, who strongly supported expansion and Manifest Destiny. Polk united his party under the idea of getting Texas and Oregon.

In August 1844, Tyler dropped out of the race. The Democratic Party was now fully committed to annexing Texas. Polk's representatives promised Tyler that Polk would annex Texas as president. So, Tyler told his supporters to vote Democratic. Polk narrowly defeated Henry Clay in November. The Democrats were ready to get Texas under Polk's idea of Manifest Destiny, not Tyler and Calhoun's pro-slavery plan.

Congress Debates Annexation

Treaty Defeat in the Senate

The Tyler-Texas annexation treaty needed two-thirds of the Senate to pass. But on June 8, 1844, two-thirds of the Senate voted against it (16-35). Most Whigs voted against it, while Democrats were split but mostly voted for it. The election campaign had made party positions on Texas stronger. Tyler expected the treaty to fail, partly because of Calhoun's controversial letter. But he still asked the House of Representatives to find other ways to approve the treaty. Congress ended its session before discussing it.

Reintroducing as a Joint Resolution

The same Senate that rejected the treaty in June 1844 met again in December 1844 for a short session. (New pro-annexation Democrats elected in the fall wouldn't take office until March 1845.) President Tyler, still trying to annex Texas in his last months, wanted to avoid another big Senate rejection. In his speech to Congress on December 4, he said Polk's victory meant people wanted Texas annexed. He suggested Congress use a joint resolution. This would only need a simple majority in each house, avoiding the two-thirds Senate requirement. Bringing the House into it was good for annexation because Democrats, who supported it, had almost a 2-to-1 majority there.

By sending the treaty back through a House bill, Tyler restarted arguments over Texas. Northern Democrats and Southern Whigs had been confused by local politics during the 1844 election. Now, Northern Democrats worried they would seem to be giving in to the South if they agreed to Tyler's pro-slavery terms. But many in the North also wanted Texas to join the U.S. quickly.

Some in the House questioned if Congress could constitutionally admit territories, not just states. Also, if Texas, a country, became a state, its borders, property (including enslaved people), debts, and public lands would need a Senate-approved treaty. Democrats were especially uneasy about the U.S. taking on $10 million in Texas debt. They didn't like that speculators had bought Texas bonds cheaply and were now pushing Congress for the bill. House Democrats were stuck and let Southern Whigs take the lead.

Brown–Foster House Amendment

Anti-Texas Whig politicians had lost the White House in 1844. In Southern states like Tennessee and Georgia, which were Whig strongholds, voter support dropped because of the excitement for annexation. Southern Whigs were seen as "soft on Texas, therefore soft on slavery" by Southern Democrats. Facing elections in 1845, some Southern Whigs wanted to change this image.

Southern Whigs in Congress, like Representative Milton Brown and Senator Ephraim H. Foster of Tennessee, worked together. On January 13, 1845, they introduced a House amendment. This amendment was designed to give slave owners in Texas even more benefits than Tyler's treaty. It proposed that Texas would join as a slave state. It would keep all its public lands and its debt from 1836. Also, the U.S. government would be responsible for settling the disputed Texas-Mexico border. This was important because Texas would be much larger if the border was the Rio Grande River instead of the Nueces River, 100 miles north. Tyler's treaty allowed for four states from Texas, three likely slave states. Brown's plan would let Texas create five states from its western region. Those south of the 36°30’ Missouri Compromise line could allow slavery if Texas chose.

Politically, the Brown amendment aimed to show Southern Whigs as even stronger supporters of slavery and the South than Southern Democrats. It also helped them stand out from Northern Whigs. While almost all Northern Whigs rejected Brown's amendment, Democrats quickly adopted it. They provided the votes to add it to Tyler's resolution, by a vote of 118–101. Southern Democrats almost all supported it (59–1), and Northern Democrats mostly supported it (50–30). Eight of eighteen Southern Whigs voted for it. Northern Whigs all rejected it. The House approved the amended Texas treaty 120–98 on January 25, 1845. The vote showed that party loyalty was stronger than regional loyalty. The bill then went to the Senate.

Benton Senate Compromise

By early February 1845, when the Senate debated the Brown-amended Tyler treaty, it seemed unlikely to pass. The Senate was almost evenly split, 28–24, slightly favoring Whigs. Democrats would need all their votes, plus three or more Whigs, to pass the bill. The fact that Senator Foster, a Whig, had helped draft the House amendment improved its chances.

Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri was the only Southern Democrat who voted against the Tyler-Texas measure in June 1844. He had proposed a compromise where Texas would be divided into half slave and half free land. As support for annexation grew in his home state, Benton changed his offer. By February 5, 1845, he proposed an alternative. Unlike Brown's plan, it didn't mention slavery in Texas. It simply called for five commissioners to resolve border disputes and set conditions for Texas to join the U.S.

Benton's idea was meant to calm Northern anti-slavery Democrats. It would also let the decision go to the new President-elect, James K. Polk. Polk wanted Texas annexation to happen before he took office on March 4, 1845. When he arrived in Washington, he found the Senate stuck between Benton's and Brown's ideas. Polk, advised by his future Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker, urged Senate Democrats to unite under a dual resolution. This resolution would include both Benton's and Brown's versions, letting Polk decide which to use when he became president. Polk privately told supporters of both plans that he would follow their policy. This helped unite Northern Democrats in favor of the dual bill.

On February 27, 1845, less than a week before Polk's inauguration, the Senate voted 27–25 to admit Texas. This was based on Tyler's idea of a simple majority vote. All 24 Democrats voted for it, joined by three Southern Whigs. Benton and his allies were assured that Polk would make the eastern part of Texas a slave state, and the western part would remain unorganized territory, not committed to slavery. With this understanding, Northern Democrats voted for the bill. The next day, the House passed the Benton-Milton measure. President Tyler signed the bill on March 1, 1845.

Annexation and Admittance

Senators and Representatives who favored Benton's version of the Texas annexation bill were told that President Tyler would sign the bill but leave its implementation to the new Polk administration. However, on his last full day in office, President Tyler, urged by Secretary of State Calhoun, decided to act quickly. On March 3, 1845, he sent an offer of annexation to Texas, using only the terms of the Brown–Foster option. Calhoun told President-elect Polk about this, and Polk didn't comment. Tyler said he acted because Polk might be pressured to abandon immediate annexation and reopen talks under Benton's alternative.

When President Polk took office on March 4, he could have recalled Tyler's message to Texas. But on March 10, after talking with his cabinet, Polk supported Tyler's action. He let the message go to Texas, offering immediate annexation. Polk only added that Texans should accept the terms without conditions. Polk made this decision because he worried that long negotiations would allow foreign countries to interfere. Polk kept his annexation efforts secret. Senators asked for official information about his Texas policy, but Polk delayed. When the Senate session ended on March 20, 1845, Polk had not named any commissioners for Texas. Polk denied misleading Senator Benton, saying he was misunderstood.

On May 5, 1845, Texas President Anson Jones called for a meeting on July 4, 1845, to consider annexation and a new constitution. On June 23, the Texas Congress accepted the U.S. Congress's resolution of March 1, 1845, to annex Texas. On July 4, the Texas meeting debated the offer and almost unanimously agreed to it. The meeting continued until August 28 and adopted the Constitution of Texas on August 27, 1845. The people of Texas approved the annexation and new constitution on October 13, 1845.

President Polk signed the law making Texas a state on December 29, 1845. Texas officially became part of the U.S. when Governor James Henderson was sworn in on February 19, 1846.

Border Disputes

The annexation law and the Texas agreement didn't clearly state Texas's borders. They only referred to "the territory properly included within, and rightfully belonging to the Republic of Texas." They also said the U.S. government would adjust any border questions with other governments.

Before annexation, Texas and Mexico had a border dispute. Texas claimed the Rio Grande River as its border, based on the Treaties of Velasco. But Mexico said the border was the Nueces River, about 100 miles north, and didn't recognize Texas's independence.

In November 1845, President James K. Polk sent a secret representative, John Slidell, to Mexico City. He offered money to Mexico for the disputed land and other Mexican territories. Mexico's government was unstable and couldn't negotiate because people were strongly against selling land. Slidell returned to the U.S.

In 1846, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to guard the southern border of Texas, as Texas claimed it. Taylor moved into Texas, ignoring Mexico's demands to leave. He marched as far south as the Rio Grande and began building a fort near the river's mouth. Mexico saw this as a violation of its land and prepared for war. After the U.S. won the war and signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico gave up its claims to Texas. The Rio Grande became the accepted border between the two nations.

How This Set a Pattern: Hawaii

There was a debate about whether annexing Texas was legal. Congress approved Texas joining as a state, not a territory, with simple majorities in each house. Usually, land is annexed by a Senate treaty, like with Native American lands. Tyler's use of a joint resolution in 1844 was unusual, but Congress passed it in 1845 as a compromise.

The success of the joint resolution for Texas set a pattern. This method was used again to annex Hawaii in 1897.

Republican President Benjamin Harrison (1889–1893) tried to annex Hawaii with a Senate treaty in 1893, but it failed. He was asked to use the Tyler joint resolution method but refused. Democratic President Grover Cleveland (1893–1897) did not try to annex Hawaii. When President William McKinley took office in 1897, he quickly tried again to get Hawaii. When he couldn't get two-thirds Senate support, committees in the House and Senate specifically mentioned the Tyler precedent. They used the joint resolution method, which successfully approved Hawaii's annexation in July 1898.

See also

In Spanish: Anexión de Texas para niños

In Spanish: Anexión de Texas para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |