Underground Railroad facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Underground Railroad |

|

|---|---|

Map of Underground Railroad routes to modern day Canada

|

|

| In | United States |

| Territory | United States, and routes to British North America, Mexico, Spanish Florida, and the Caribbean |

| Ethnicity | African Americans and other compatriots |

| Criminal activities |

|

| Allies |

|

| Rivals | Slave catchers, Reverse Underground Railroad |

The Underground Railroad was a secret system of paths and safe places. It was set up in the United States in the early to mid-1800s. Enslaved African Americans used it to escape to freedom. Most went to "free states" in the North or to Canada.

People who helped these escapees were called "abolitionists." They were against slavery. The enslaved people who risked their lives to escape, and those who helped them, are also known as the "Underground Railroad." Some routes also led to Mexico or islands in the Caribbean. Slavery had been ended in these places. By 1850, it's thought that about 100,000 enslaved people found freedom through this network.

Contents

Why People Escaped to Freedom

Many enslaved people dreamed of reaching Canada. Between 1850 and 1860, about 30,000 to 40,000 freedom seekers settled there. Others found safety in free states in the northern U.S.

Laws made it hard for enslaved people to escape. The first Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 said that officials in free states had to help slave owners catch people who had escaped. This law also made it easy for slave catchers to kidnap free Black people and sell them into slavery. This unfairness made more people want to help enslaved people escape. It led to the growth of anti-slavery groups and the Underground Railroad.

Later, the Compromise of 1850 brought an even stricter Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law forced officials in free states to help slave catchers. It also meant that people suspected of being enslaved had no right to a trial. They could not even speak up for themselves in court. This made it very dangerous for all Black people, even those who were free. Some northern states passed "personal liberty laws" to protect former slaves. But many southern politicians used the idea that northern states ignored these laws as a reason to separate from the U.S.

How the Underground Railroad Worked

The Underground Railroad was not a real railroad. It was a secret network of meeting spots, hidden paths, and safe houses. These were kept secret by people who were against slavery. They shared information by word of mouth.

People escaping slavery would travel north from one safe place to the next. "Conductors" were guides who helped them. These conductors came from many backgrounds. They included free-born Black people, white abolitionists, and formerly enslaved people. Native Americans also helped. Many Christian groups, especially Quakers, helped because they believed slavery was wrong. Free Black people played a very important role. Without them, it would have been almost impossible for many to reach freedom.

Secret Language of the Railroad

The Underground Railroad used special code words, like a real railway.

- People who helped find the railroad were "agents" or "shepherds."

- Guides were called "conductors."

- Hiding places were "stations" or "way stations."

- "Station masters" hid escaping slaves in their homes.

- People escaping slavery were "passengers" or "cargo."

- Enslaved people would get a "ticket."

- Money helpers were "stockholders."

The Big Dipper constellation was called the "drinkin' gourd." Its "bowl" points to the North Star, which guided people north. The Railroad was also called the "freedom train" or "Gospel train." It headed towards "Heaven" or "the Promised Land," which meant Canada.

William Still, known as "The Father of the Underground Railroad," helped hundreds of enslaved people escape. He often hid them in his Philadelphia home. He kept careful records, using railway words in his notes. He later published these stories in a book. This book helps historians understand how the system worked.

Messages were often coded so only those involved could understand them. For example, "I have sent via at two o'clock four large hams and two small hams" meant four adults and two children were sent by train. The word via meant they were on a different, secret train. This tricked authorities while Still guided the escapees to safety.

To stay safe, most people involved in the Underground Railroad knew only their small part of the plan. "Conductors" led "passengers" from one station to the next. Sometimes, a conductor would pretend to be enslaved to enter a plantation. Once inside, they would guide people north. Enslaved people traveled at night, usually about 10 to 20 miles to each station. They rested during the day in "stations" or "depots," which were often basements, barns, churches, or caves.

Canada was called the "Promised Land" or "Heaven." The Ohio River, which divided slave states from free states, was called the "River Jordan."

Traveling Conditions and Dangers

Freedom seekers usually traveled on foot or by wagon. They sometimes hid under hay. Groups were often small, one to three people, but sometimes larger. Abolitionist Charles Turner Torrey sometimes moved 15 to 20 people at once. Free and enslaved Black sailors also helped by giving rides on ships or sharing information about safe routes.

Routes were often indirect to confuse anyone chasing them. Escaping was especially hard and dangerous for women and children. Children could be hard to keep quiet, and women were often not allowed to leave plantations easily. However, many women, like Harriet Tubman, were very successful conductors.

Information was passed by word of mouth to avoid discovery. Southern newspapers often had ads asking for information about escaped slaves. They offered large rewards. Federal marshals and professional bounty hunters, called slave catchers, chased freedom seekers all the way to the Canadian border.

The "Reverse Underground Railroad"

Not only freedom seekers were at risk from slave catchers. Free Black people were also in danger. With high demand for enslaved people in the Deep South, strong, healthy Black individuals were very valuable. Both former slaves and free Black people were sometimes kidnapped and sold into slavery. A famous example is Solomon Northup, a free Black man from New York who was kidnapped in Washington D.C. "Certificates of Freedom" (free papers) were supposed to prove a person was free, but they could easily be stolen or destroyed.

Some places, like the Crenshaw House in Illinois, were known sites where free Black people were sold into slavery. This was called the "Reverse Underground Railroad."

Arrival in Canada

British North America (now Canada) was a popular destination. It had a long border, was far from slave catchers, and was beyond the reach of U.S. fugitive slave laws. Slavery had ended in Canada much earlier than in the U.S. Britain banned slavery in most of its colonies, including Canada, in 1833.

Most formerly enslaved people who reached Canada settled in Ontario. More than 30,000 people are thought to have escaped there during the peak years of the network. Many stories are recorded in William Still's 1872 book, The Underground Railroad Records.

Large Black Canadian communities grew in Southern Ontario. Villages made up mostly of people freed from slavery were set up in Kent and Essex counties. Fort Malden in Amherstburg, Ontario, was a main entry point for those seeking freedom in Canada.

Life in Canada was still difficult. While safe from slave catchers, people faced discrimination. Many new arrivals had to compete for jobs with European immigrants, and racism was common. For example, the city of Saint John, New Brunswick, changed its rules in 1785 to stop Black people from working in certain trades.

When the Civil War began in the U.S., many Black refugees left Canada to join the Union Army. After the war, thousands returned to the American South. They wanted to reunite with family and hoped for a better life after slavery ended.

Stories and Songs

Since the 1980s, some people have claimed that quilt designs were used to send secret messages to enslaved people. They say different quilt patterns told people when to escape and what direction to go. However, historians who study quilts and the pre-Civil War era have found no real proof of this "quilt code."

Similarly, some popular sources say that spiritual songs, like "Steal Away" or "Follow the Drinking Gourd," contained secret codes for escape. Scholars generally believe that these songs expressed hope for freedom but did not give literal instructions for runaway slaves.

The Underground Railroad has inspired many stories, books, and songs. For example, "Song of the Free" (1860) was about a man escaping slavery to Canada. It used the tune of "Oh! Susanna" and ended each verse by saying Canada was the land "where colored men are free."

The Underground Railroad in the South

Some routes of the Underground Railroad also went south to Spanish Florida and Mexico. In the 16th century, Spain brought enslaved Africans to what is now St. Augustine. Later, Charles II of Spain declared Spanish Florida a safe place for escaped slaves. They began escaping there by the hundreds.

In Mexico, slavery was abolished in 1829 by President Vicente Guerrero, who was of mixed race. This made Mexico a place of hope for enslaved people in the U.S. In the United States, enslaved people were seen as property, with no rights. But in New Spain (Mexico), escaped slaves were seen as humans. They could join the Catholic Church and marry.

Thousands of freedom seekers traveled from the southern U.S. to Texas and then to Mexico. They often traveled on foot or horseback through difficult, hot land. Some hid on ferries going to Mexican ports.

Help Along the Southern Routes

Some people traveled alone, but others were helped. This help included guidance, shelter, and supplies. Black people, mixed-race couples, and anti-slavery German immigrants offered support. Most help came from Mexican laborers. Slave owners in Texas became so distrustful that a law was passed forbidding Mexicans from talking to enslaved people.

Some border officials in Mexico helped. In Monclova, Mexico, an official collected money for a family needing food and clothes to continue their journey south. Once across the border, Mexican authorities sometimes protected former enslaved people from slave hunters.

Because of the dangers, people were very careful to keep their actions secret. Records about freedom seekers are rare. However, the Texas Runaway Slave Project at Stephen F. Austin State University has documented over 2,500 escapes from Texas.

Life in Mexico

When freedom seekers reached Mexico, they knew they could still be kidnapped by slave catchers. However, slave hunters who tried to kidnap former slaves could be taken to court or even shot.

Life was still hard. There was often little support from new communities and few job opportunities. They did not have official papers proving they were free. But they could join military colonies or sign contracts for work. Some people later returned to the U.S. to help family members escape and guide them to Mexico.

Two families, the Webbers and the Jacksons, lived along the Rio Grande and helped people escape. The husbands were white, and the wives were Black women who had been enslaved. They owned ferry services and were well-known among runaways.

Remembering the Underground Railroad

In 1998, the U.S. government created the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program. This program identifies and preserves sites connected to the Underground Railroad. It also shares the stories of the people involved. The National Park Service manages this program.

Parks like the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Maryland and the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in New York honor Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad.

Images for kids

-

"The Old Stone Fort of Nacogdoches," by Lee C. Harby, The American Magazine, April 1888 edition

-

Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves, oil on paperboard, 22 × 26.25 inches, c. 1862, Brooklyn Museum. Depicts a family of African Americans fleeing enslavement in the Southern United States during the American Civil War

-

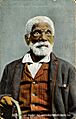

Tom Blue, enslaved by General Sam Houston, ran away and joined the Mexican military

See also

In Spanish: Ferrocarril subterráneo para niños

In Spanish: Ferrocarril subterráneo para niños

- Angola, Florida

- Ausable Chasm, NY, home of the North Star Underground Railroad Museum

- Bilger's Rocks

- Caroline Quarlls (1824–1892), first known person to escape slavery through Wisconsin's Underground Railroad

- Escape to Sweden, an "underground railroad" during the Holocaust in Norway

- Fort Mose Historic State Park

- List of Underground Railroad sites

- Reverse Underground Railroad

- Slave codes

- Tilly Escape

- Timbuctoo, New York

- Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site near Dresden, Ontario

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |