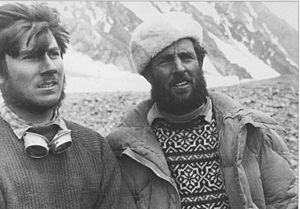

Walter Bonatti facts for kids

Walter Bonatti in 1964

|

|

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Born | 22 June 1930 Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy |

| Died | 13 September 2011 (aged 81) Rome, Lazio, Italy |

| Climbing career | |

| Type of climber | Mountaineer |

| Known for | Solo climb of Aiguille du Dru |

| First ascents | Gasherbrum IV |

| Major ascents | List of mountaineering achievements |

| Updated on 18 March 2013. | |

Walter Bonatti (born June 22, 1930 – died September 13, 2011) was a famous Italian mountain climber, explorer, and journalist. He was known for many amazing climbing achievements. These included a difficult solo climb of a new route on the Aiguille du Dru in 1955. He also made the first climb of Gasherbrum IV in 1958. In 1965, he completed the first solo climb in winter of the North face of the Matterhorn.

Right after his Matterhorn climb, Bonatti decided to stop professional climbing. He was 35 years old and had been climbing for 17 years. He wrote many books about mountaineering. He then spent the rest of his career traveling to faraway places as a reporter for the Italian magazine Epoca.

Walter Bonatti passed away on September 13, 2011, in Rome at age 81. He was with his life partner, the actress Rossana Podestà. He was known for his daring climbing style. He also explored new and very hard climbing routes in the Alps, Himalayas, and Patagonia. In 2009, Bonatti received the first-ever Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award. Many people believe he was one of the greatest climbers in history.

Contents

- Walter Bonatti's Life and Climbing Adventures

- Early Climbs and Big Challenges

- The K2 Expedition: A Difficult Story

- Aiguille du Dru: A Solo Masterpiece

- The Vincendon and Henry Tragedy

- More Alpine Challenges

- Exploring Patagonia

- First Ascent of Gasherbrum IV

- Adventures in Cordillera Huayhuash

- The Frêney Pillar Tragedy

- Grandes Jorasses: A Technical Climb

- The Matterhorn Solo Climb

- Life After Climbing: Reporter and Explorer

- Walter Bonatti's Personal Life

- Walter Bonatti's Climbing Philosophy

- Awards and Recognition

- Walter Bonatti's Legacy and Influence

- List of Main Mountaineering Achievements

- Books by Walter Bonatti

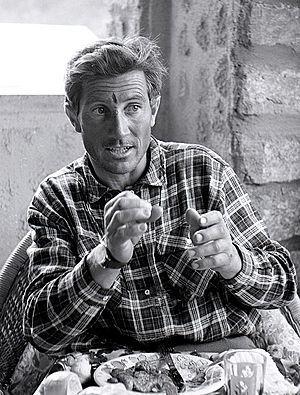

- Images for kids

- See also

Walter Bonatti's Life and Climbing Adventures

Walter Bonatti grew up in Bergamo, Italy. He was an only child. His family was poor after World War II. His father sold fabric. Walter found his passion in gymnastics through a sports club in Monza. The strength and balance he gained were very important for his climbing skills. At 18, Bonatti started climbing on the Grigna mountain in Italy. He spent the summer of 1948 climbing a lot.

In 1949, just one year after starting, he repeated a very hard climb. This was the Oppio-Colnaghi-Guidi Route on the South Face of the Croz dell'Altissimo. Soon after, he climbed the Bramani-Castiglioni Route on Piz Badile. He also repeated the Ratti-Vitali route on the Aiguille Noire de Peuterey. Then, he made the fourth climb of the Walker Spur on the North Face of the Grandes Jorasses. He did this in just two days with little gear. This route is 1,200 meters (3,900 feet) of rock climbing. It is known for being very difficult and exposed to falling rocks.

Bonatti did not have much money. His first climbs used very basic equipment. He even made some of his own climbing pitons. In his early years, Bonatti worked in a steel mill. He would climb on Sundays right after his Saturday night shift. In less than two years, he became one of Italy's best climbers.

Early Climbs and Big Challenges

In 1950, Bonatti tried to achieve a major goal: climbing the east face of the Grand Capucin. This was a never-before-climbed granite face in the Mont Blanc area. He tried with Camillo Barzaghi, but a storm stopped them. Three weeks later, he tried again with Luciano Ghigo. They climbed for three days but another storm forced them back.

In 1951, the same team tried the Grand Capucin again. They started on July 20 in good weather. They got close to the top in two days. But the weather got worse, and they had to spend a day on the face. The next day, they finished the climb and returned safely. Later, another famous climber, Hermann Buhl, called it the "most difficult granite climb." In 1952, Bonatti and Roberto Bignami opened a new route on the Aiguille Noire de Peuterey.

In February 1953, Bonatti and Carlo Mauri made the first winter climb of the north face of Cima Ovest di Lavaredo. A few days later, they repeated the winter climb of Cima Grande. Before winter ended, Bonatti and Roberto Bignami opened a new route on the Matterhorn. In the summer of 1953, he made the first climb of Mont Blanc from the Peuterey Col.

In 1954, Bonatti joined the Alpine regiment. He trained climbers four days a week. The other three days, he could climb on his own. Because of his many achievements, he was chosen for the Italian expedition to K2. This trip would later cause him problems.

The K2 Expedition: A Difficult Story

Bonatti was the youngest climber on the 1954 Italian expedition to K2. This expedition was led by Ardito Desio. Bonatti later said that this was a time when European countries were trying to conquer the highest mountains, like they had conquered colonies. On July 31, two Italian climbers, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, reached the summit. This was the first time K2 was climbed.

However, years after the expedition, Bonatti faced a lot of disagreement. There were different stories about what happened during the climb. It took 53 years for the Italian Alpine Club to officially say that Lacedelli and Compagnoni had not told the full truth. They confirmed that Bonatti's story was accurate.

Bonatti and a climber named Amir Mehdi had to carry oxygen tanks up to Camp IX. These tanks were for Lacedelli and Compagnoni to use for their summit attempt. But Compagnoni decided to move Camp IX higher than they had agreed with Bonatti. Bonatti and Mehdi got close to the new Camp IX. But it was night, and Mehdi was getting very sick.

Bonatti knew they needed a tent to survive the night at that height. Without it, they risked severe frostbite. But the Camp IX tent was on a dangerous icy path. It was too dark to reach it. Mehdi was too weak to climb further or go back to Camp VIII. So, Bonatti and Mehdi had to spend the night outside without a tent or sleeping bag. This was at 8,100 meters (26,570 feet) and -50°C (-58°F). Mehdi lost his toes from frostbite. Bonatti was lucky to survive unharmed.

Compagnoni said he moved the camp to avoid falling ice. But Bonatti believed they moved it on purpose. He thought they wanted to stop him and Mehdi from staying at that height. This would prevent them from trying for the summit themselves. Bonatti was the strongest climber and a natural choice for the summit team. But Ardito Desio chose Lacedelli and Compagnoni. If Bonatti had joined, he likely would not have used extra oxygen. This might have made Lacedelli and Compagnoni's oxygen-assisted climb seem less impressive.

On the morning of July 31, Bonatti and Mehdi started going down to Camp VIII. Compagnoni and Lacedelli then picked up the oxygen tanks. They reached the K2 summit at 6:10 PM. Ardito Desio's final report barely mentioned Bonatti and Mehdi's difficult night. Mehdi's frostbite was a problem for the expedition.

Compagnoni later accused Bonatti of using some oxygen during his night outside. He said this caused them to run out of oxygen too early on summit day. Bonatti immediately said he couldn't use the oxygen. The mask and regulator were at Camp IX. Bonatti showed proof that Compagnoni had lied about running out of oxygen. Lacedelli later supported Bonatti's story in his book. He said the oxygen did run out, but not because Bonatti used it. It was because they used more oxygen than expected during the hard climb.

For a long time, some climbers blamed Bonatti. But over time, more and more proof showed he was honest. Reinhold Messner, a famous climber, said in 2010: "Bonatti was one of the greatest climbers of all time... He was a clean man blamed for 50 years over what happened on K2, but in the end everyone accepted that he was right."

In 2007, the Italian Alpine Club released a new official report. It fully accepted Bonatti's version of the K2 events. Bonatti tried to climb K2 alone without oxygen the next year. He wanted to set the record straight. But he couldn't get support. So, he became a mountain guide in Courmayeur in 1954.

Aiguille du Dru: A Solo Masterpiece

Years later, Bonatti wrote: "After what happened in 1954, I started to mistrust people. I tended to rely only on myself."

In August 1955, after two tries stopped by bad weather, Bonatti made a solo climb. He opened a new route on the south-west pillar of the Aiguille du Dru in the Mont Blanc area. This climb was extremely difficult. It took him six days and five nights spent hanging on the rock face. Even today, it is seen as an amazing climbing achievement.

After five days of climbing on a vertical rock with little protection, Bonatti got stuck. He faced a section that was impossible to climb directly. The rock on both sides was completely smooth. Bonatti used all his ropes and slings. He tied one end into a crack. Then, he swung on the other end to get past the difficult part. This route became known as the Bonatti Pillar. It is still considered one of the greatest climbs in alpinism. To get past long vertical sections and overhangs, Bonatti had to use special aid climbing techniques.

Sadly, in 2005, a huge landslide completely destroyed the Bonatti Pillar route.

The Vincendon and Henry Tragedy

In December 1956, Bonatti and Silvano Gheser tried a winter climb on Mont Blanc. They met two other climbers, Jean Vincendon and François Henry, who were on an easier route nearby. Both teams started climbing on Christmas Day in good weather. After a few hours, ice conditions on Bonatti's route became dangerous. He and Gheser had to move to the Brenva Spur, where the other team was. The two teams climbed on different but parallel paths.

Near the end of the climb, a strong storm began. Both teams had to spend an unplanned night outside at 4,100 meters (13,450 feet). Bonatti and Gheser survived the night. But Gheser started to get frostbite on his foot. On December 26, Bonatti and Gheser went down to join the other team. The four climbers continued together. They reached the Brenva Col.

From there, they had two choices: go down to Chamonix through dangerous snow, or climb to the summit of Mont Blanc and then go down to a hut. Bonatti chose the second option. It was safer but longer and harder, needing them to climb 500 meters (1,640 feet) higher in a winter storm. Bonatti urged them to climb fast. Gheser's feet and hands were badly frostbitten. They reached the Vallot Hut after dark.

Meanwhile, Vincendon and Henry decided to turn back, 200 meters (650 feet) from the Mont Blanc summit. They tried to go straight to Chamonix. But darkness forced them to spend the night in a crevasse at 4,600 meters (15,100 feet). Bonatti and Gheser left the Vallot Hut on December 27. They went down the Italian side of Mont Blanc. A rescue team reached them on December 30.

Vincendon and Henry were very tired and frostbitten. They waited in the crevasse for rescue. But bad weather stopped rescue efforts. Many attempts were made, including a helicopter that crashed. All failed. Both climbers died from the cold after 10 days. Their bodies were found in March 1957. This sad event led to new mountain rescue methods in France.

More Alpine Challenges

In 1957, Bonatti moved to Courmayeur. After recovering from his Brenva Spur climb, he focused on the last big unclimbed face in the Mont Blanc area: the north face of the Grand Pilier d'Angle. Between 1957 and 1963, he opened three new routes there. He climbed with Toni Gobbi in 1957. He also climbed twice with Cosimo Zappelli in 1962 and 1963. All these routes are very difficult.

Bonatti said that the mixed rock and ice on the north-east face of the Grand Pilier d'Angle was "the most sombre, the most savage and the most dangerous of any that I have ever encountered in the Alps." On March 9, 1961, Bonatti and Gigi Panei made the first winter climb of the Via della Sentinella Rossa on Mont Blanc. They did it in a record 11 hours.

Exploring Patagonia

In January 1958, Bonatti went to Patagonia, Argentina. He joined an Italian-Argentinian team to climb in the icy mountains. Their goal was to climb the unclimbed Cerro Torre (3,128 meters or 10,262 feet) with Carlo Mauri. They started on February 2 in good weather. But the route was very hard, and they didn't have enough climbing gear. It seems the climb was too difficult for even the best climbers of that time. The first confirmed climb of Cerro Torre happened only in 1974.

During the same trip, Bonatti, with René Eggmann and Folco Doro Altán, climbed two other unclimbed mountains. They ascended Cerro Mariano Moreno on February 4 and Cerro Adela on February 7. In the next few days, they climbed Cerro Doblado, Cerro Grande, and Cerro Luca (climbed for the first time). Cerro Luca was named after Mauri's son. This impressive journey across three mountains is now called Travesía del Cordón Adela.

First Ascent of Gasherbrum IV

In 1958, Bonatti joined another Italian expedition. This one was led by Riccardo Cassin to the Karakoram mountains in Pakistan. Their goal was to climb the unclimbed Gasherbrum IV (7,925 meters or 26,000 feet). This is the 17th highest mountain on Earth. On August 6, Bonatti and Carlo Mauri reached the summit. They climbed it in a fast, lightweight style up the north-east ridge.

Adventures in Cordillera Huayhuash

In May 1961, Walter Bonatti and Andrea Oggioni climbed Nevado Ninashanca (5,607 meters or 18,396 feet). They also made the first climb of Rondoy Norte (5,789 meters or 18,993 feet). This is a remote peak in the Cordillera Huayhuash. They climbed its west face, which is a very serious and difficult route. Few people have climbed it since.

The Frêney Pillar Tragedy

In the summer of 1961, Walter Bonatti, Andrea Oggioni, and Roberto Gallieni planned to climb the Central Pillar of Frêney. This was an unclimbed peak in the Mont Blanc area. At their camp, they met a French team of four climbers. The two teams decided to climb together.

A snowstorm lasted more than a week. It trapped the two teams just 100 meters (330 feet) from the top of the pillar. Meanwhile, two mountain guides realized Bonatti had not returned. They found a note from Bonatti in a hut, explaining their climb. Bonatti and the others were stuck. They hadn't moved for three days. Finally, they decided to go down. But only three climbers survived: Bonatti, Gallieni, and Pierre Mazeaud. The other four died from exhaustion or accidents in the fresh snow.

In 2002, French President Jacques Chirac gave Bonatti a special award. It was the National Order of the Legion of Honor. This was for his bravery and kindness in trying to save his fellow climbers. The Central Pillar of Frêney was finally climbed a few days later. On August 29, 1961, Chris Bonington, Ian Clough, Don Whillans, and Jan Długosz were the first to complete this "Last Great Problem of the Alps."

Grandes Jorasses: A Technical Climb

In four days, from August 6 to 10, 1964, Bonatti made the first climb of Pointe Whymper. This is one of the six summits of the Grandes Jorasses. He climbed with Michel Vaucher. This route, now called the Bonatti-Vaucher route, is still considered very technical and hard. It involves 1,100 meters (3,600 feet) of rock climbing. It also has sections of mixed rock and ice climbing.

The Matterhorn Solo Climb

In February 1965, Bonatti tried to climb a new, direct route on the Matterhorn Nordwand (north face). He was with two friends. But a storm forced them back. Back in the valley, his friends had to leave. Bonatti thought about it, then set off alone on February 18, 1965, for a second try. Five days later, he reached the summit. He had completed a very demanding 1,200-meter (3,900-foot) climb. This solo winter climb has been rarely repeated.

Soon after this climb, Walter Bonatti announced he was retiring from professional climbing. He was 35 years old and had been climbing for 17 years.

Life After Climbing: Reporter and Explorer

After retiring from climbing, Bonatti worked for over 20 years as a reporter. He wrote for the Italian magazine Epoca. He traveled to many remote and wild places. Here are some of his most notable trips:

- 1965: He went to Alaska to explore the Pribilof Islands.

- 1966: He traveled to Uganda and Tanzania. He climbed Kilimanjaro and the Ruwenzori. He followed the path of Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, from 1906. He crossed 1,200 km (750 miles) of wild jungle alone.

- 1967 and 1973: He explored the Orinoco and Amazon River in South America.

- 1968: He visited the island of Sumatra. He studied tigers and met the Sakai, who are Aboriginal people from Malaysian jungles.

- 1969: He explored the center of Australia and Lake Eyre.

- 1969: He went to the Marquesas Islands. He followed the jungle journey described by Melville. He found the same places, proving Melville's story was true.

- 1971: He visited Cape Horn.

- 1971: He climbed Aconcagua in Argentina.

- 1972: He climbed the Nyiragongo Volcano in Zaire and Congo.

- 1974: He went to New Guinea to meet local tribes.

- 1976: He explored the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica with scientists.

- 1978: He returned to South America to find the sources of the Amazon River.

- 1985–1986: He explored the Patagonian Southern Patagonian Ice Field in Chile.

Many of these adventures are described in his book In terre lontane.

Walter Bonatti's Personal Life

In 1980, Bonatti met the former actress Rossana Podestà in Rome. They soon moved to Dubino, a small town in the Alps.

Walter Bonatti passed away at age 81. He was alone in a private clinic. The hospital would not let his partner of over 30 years be with him in his final moments. This was because they were not married. His funeral was held in Lecco on September 18, 2011. He was cremated, and his ashes were buried in the cemetery of Porto Venere.

Walter Bonatti's Climbing Philosophy

Walter Bonatti called his climbing philosophy "The pursuit with the extremely hard." He completed many daring climbs. He also survived terrible climbs that killed some of his friends. His main idea was to climb mountains as they are, using fair methods, and in the simplest and most beautiful way possible. In an interview in 2010, he said: "Modern equipment is so technically advanced you can climb anything if you put your mind to it. The impossible has been removed from the equation."

He was strongly against using expansion bolts, which are permanent anchors drilled into rock. Reinhold Messner, another famous climber, agreed with Bonatti. He said that "Expansion bolts contribute to the decline of alpinism."

In his book The Mountains of My Life, Walter Bonatti wrote:

For me, the value of a climb is the sum of three inseparable elements, all equally important: aesthetics, history, and ethics. Together they form the whole basis of my concept of alpinism. Some people see no more in climbing mountains than an escape from the harsh realities of modern times. This is not only uninformed but unfair. I don’t deny that there can be an element of escapism in mountaineering, but this should never overshadow its real essence, which is not escape but victory over your own human frailty.

Awards and Recognition

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- Rome, December 2, 2004

- Bonatti later refused this honor because it was also given to Achille Compagnoni.

- Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honor

- Paris, June 2002

- Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award, the first time this award was given.

- 2009

Walter Bonatti's Legacy and Influence

Walter Bonatti's life has inspired many generations of climbers in Italy and around the world.

A mountain hut in the Val Ferret, at 2,025 meters (6,644 feet), is named after Bonatti. It is called Refuge Walter-Bonatti.

In 2009, Bonatti received the Piolet d'Or for his lifetime achievements. After he passed away, the Piolet d'Or prize for lifetime achievement was renamed the Piolet d'Or for lifetime achievement, Walter Bonatti prize.

British climber Doug Scott wrote in 1974 that Bonatti was "perhaps the finest alpinist there has ever been." In 2010, Reinhold Messner called him "one of the greatest climbers of all time and a marvellous person."

The legendary Chris Bonington said about Bonatti: "He was a complex person and a sensitive one too. K2 always worried him. But he was also a man of great honesty. And a great gentleman."

French climber Pierre Mazeaud said: "There is spirituality in that person. For me, Walter is undoubtedly a legendary hero but he is above all a man of truth who has a big heart."

Gaston Rebuffat described Bonatti as: "A man with ideals, but also with the precious human qualities making possible ideals to become real."

In May 2012, the first movie about Bonatti's life was made. It was called Con i muscoli, con il cuore, con la testa. The movie started production before Bonatti's death and was slightly changed afterward.

List of Main Mountaineering Achievements

Here are some of Walter Bonatti's most important climbs:

- Oppio-Colnaghi-Guidi Route – Croz dell'Altissimo – June 27–29, 1949 – First repeat with Andrea Oggioni and Iosve Aiazzi

- Ratti-Vitali Route – Aiguille Noire de Peuterey – August 13–14, 1949 – Third repeat with Andrea Oggioni and Emilio Villa

- Cassin Route – Grandes Jorasses (Walker spur) – August 17–19, 1949 – Fifth repeat with Andrea Oggioni

- Gaiser-Lehmann Route – Pizzo Cengalo – June 30 – July 2, 1950 – First repeat with C. Casati

- Bonatti-Nava Route – Punta Sant'Anna – August 6–7, 1950 – First climb of the north ridge

- Bonatti-Ghigo Route – Grand Capucin – July 20–23, 1951 – First climb of the east face

- Cassin Route – Cima ovest di Lavaredo – February 1953 – First winter climb with Carlo Mauri

- Bonatti-Gobbi Route – Grand Pilier d'Angle – August 1–3, 1957 – First climb of the east face with Toni Gobbi

- Northeast ridge – Gasherbrum IV – August 6, 1958 – First climb with Carlo Mauri

- Runtuy North – May 1961 – First climb with Andrea Oggioni

- Sentinella Rossa Route – Mont Blanc – March 9, 1961 – First winter climb with Gigi Panei

- Bonatti-Zappelli Direct Route – Mont Blanc (Frêney) – September 20–22, 1961 – First climb with Cosimo Zappelli

- Bonatti-Zappelli Route – Grand Pilier d'Angle – June 22–23, 1962 – First climb of the north face with Cosimo Zappelli

- Cassin Route – Grandes Jorasses – January 25–30, 1963 – First winter climb with Cosimo Zappelli

- Bonatti-Zappelli Route – Grand Pilier d'Angle – October 11–12, 1963 – First climb of the south face with Cosimo Zappelli

- North ridge – Trident du Tacul – July 30, 1964 – First climb with Livio Stuffer

- Bonatti-Vaucher Route – Grandes Jorasses (Pointe Whymper) – August 6–10, 1964 – First climb of the north face with Michel Vaucher

Routes Climbed Solo

- Bonatti Route – Aiguille du Dru – August 17–22, 1955 – First solo climb of the south-east pillar

- Major Route – Mont Blanc (Brenva) – September 13, 1959 – First solo climb.

- South-East face – Brenva Col – March 28, 1961 – First solo climb

- Bonatti Route – Matterhorn – February 18–22, 1965 – First solo and winter climb of a new route on the north face

Books by Walter Bonatti

Walter Bonatti wrote many books. Most of them have been translated into different languages.

- Le Mie Montagne (My Mountains), 1961

- I Giorni Grandi (The Great Days), 1971

- Magia del Monte Bianco (Magic of Mont Blanc), 1984

- Processo al K2 (Trial on K2), 1985

- La Mia Patagonia (My Patagonia), 1986

- Un Modo di Essere (A Way of Living), 1989

- K2 Storia di un Caso (K2 – The Story of a Court Case), 1995

- Montagne di Una Vita (Mountains of a Life), 1995

- K2 Storia di un Caso (K2 – The Story of a Court Case) 2nd edition, 1996

- In terre lontane (In Far Away Lands), 1998

- The Mountains of My Life, 2010

- K2 La verità. 1954–2004" (K2 The Truth), 2005

- Un mondo perduto: viaggio a ritroso nel tempo (A Lost World: Journey Back in Time), 2009

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Walter Bonatti para niños

In Spanish: Walter Bonatti para niños