West Kill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids West Kill |

|

|---|---|

Diamond Notch Falls on the upper West Kill

|

|

|

Location of the mouth of the West Kill

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| Region | Catskills |

| County | Greene |

| Towns | Hunter, Lexington |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | W slope of Hunter Mountain 3,100 ft (940 m) 42°10′24″N 74°14′15″W / 42.17333°N 74.23750°W |

| River mouth | Schoharie Creek Lexington, New York 1,299 ft (396 m) 42°14′45″N 74°22′36″W / 42.24583°N 74.37667°W |

| Length | 11 mi (18 km), E-W |

| Discharge (location 2) |

|

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 31.2 sq mi (81 km2) |

| Tributaries | |

| Waterfalls | Diamond Notch Falls |

The West Kill is a beautiful river in New York State. It flows for about 11 miles (18 km) through the town of Lexington, New York. This river starts high up on Hunter Mountain, which is the second-tallest peak in the Catskill Mountains. The West Kill is a tributary of Schoharie Creek, and its waters eventually reach the Hudson River.

Because the West Kill flows into the Schoharie Creek upstream of the Schoharie Reservoir, its water is an important part of the New York City water supply system. The river is so important that it even gave its name to a nearby mountain, West Kill Mountain, and a small town called West Kill, New York.

The land area that drains into the West Kill, called its watershed, covers about 31.2 square miles (81 km2). This watershed makes up 10 percent of the entire Schoharie Reservoir's basin. It has some of the highest and steepest areas of all the streams that feed into the Schoharie Creek. Water from seven of the 35 highest peaks in the Catskills flows into the West Kill.

The West Kill watershed has not been developed much, and a lot of its land is protected. This means the water is quite clean. It's a great home for both wild and stocked trout, which are fish that are added to the river. Because of this, the West Kill has always been popular with people who enjoy fly fishing and other types of fishing.

Contents

Journey of the West Kill River

The West Kill river starts its journey high in the mountains and flows through different areas before joining the Schoharie Creek.

Where Does the West Kill Start?

The first 8 miles (13 km) of the West Kill flow west through a place called the Spruceton Valley. After that, it turns more to the north until it reaches the Schoharie at Lexington.

Two small streams begin in a bowl-shaped area between Hunter and Southwest Hunter mountains. This area is covered by thick forests in the West Kill Wilderness Area, which is part of the Catskill Park. The northern stream starts at about 3,100 feet (940 m) high. It flows quickly down a narrow path for its first quarter-mile (400 m).

Below 2,700 feet (820 m) in elevation, the land becomes less steep. The two streams join together where the towns of Hunter and Lexington meet. The West Kill then flows downhill for about half a mile (800 m). A hiking trail called the Devil's Path gradually gets closer to the stream and follows it on its north side.

At Diamond Notch Falls, the Devil's Path trail briefly meets another trail called the Diamond Notch Trail. Both trails cross the West Kill on a wooden bridge. This is the highest point where a bridge crosses the stream. The trails then split again. The Devil's Path follows the stream for a short distance before climbing West Kill Mountain. The Diamond Notch Trail runs next to the river for another 0.7 miles (1.1 km) to a parking lot. This area is at about 2,220 feet (677 m) high.

Soon after, the valley starts to get a little wider. The West Kill gets its first unnamed stream joining it from the slopes of West Kill Mountain to the south. As the river flows west, it passes some open areas and buildings. Its first named stream, Hunter Brook, flows in from the north. Then, Pettit Brook joins from the south.

More small streams join the West Kill as it continues its journey. Herdman Brook flows in from the north near the old village of Spruceton. Then, Styles Brook joins from the south, draining water from below West Kill Mountain. Fields and buildings are now found on both sides of the stream.

The West Kill continues to flow west, with more unnamed streams joining from the mountains. Hagadone Brook flows in from the south, and Schoolhouse Brook joins from the north. Then, Bennett Brook flows in from the south.

Further downstream, Newton Brook joins from the slopes of Mount Sherrill to the south. As the West Kill reaches the small town of West Kill, its elevation drops below 1,500 feet (460 m).

West Kill's Journey After the Hamlet

After passing north of the hamlet of West Kill, the river starts to turn towards the northwest. It widens briefly in an area with several sand and gravel bars. The stream then narrows again and flows under New York State Route 42. It continues to flow generally north, running parallel to the highway. Along this stretch, three unnamed streams join from the west.

About a mile (1.6 km) north of West Kill, Beech Ridge Brook flows in from the west. Just north of this point, the West Kill crosses under Route 42. For about 800 feet (240 m), both sides of the river are reinforced with rocks to prevent erosion. The natural banks return where Roarback Brook, the last stream to join the West Kill, flows in from the west.

After another mile (1.6 km), the West Kill crosses under Route 42 for the last time. This is just west of the hamlet of Lexington. Soon after, it turns east and then slightly southeast to meet the Schoharie Creek. At this point, the river is just above 1,300 feet (400 m) in elevation.

The West Kill Watershed

The West Kill's watershed is the area of land where all the rain and snow eventually drain into the West Kill river. This watershed covers about 31.2 square miles (81 km2). It makes up 10 percent of the total watershed for the Schoharie Reservoir. Most of the West Kill watershed is in the town of Lexington. The eastern part, where the river starts, is in Hunter. Some areas where its western streams begin are in the town of Halcott.

The highest point in the West Kill watershed is the top of Hunter Mountain, which is about 4,040 feet (1,230 m) high. This is also the highest point in the Schoharie and Mohawk watersheds. Overall, the West Kill watershed has the highest elevation of any area that drains into the Schoharie basin. It also has the steepest average slope, which means the land is very hilly.

Most of the land in the watershed is open space. Nearly two-thirds of the land, about 16,182 acres (65.49 km2), is kept undeveloped. Much of this is forested land on the mountains. Most of these forests are protected areas managed by the state's Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC).

Most of the watershed is inside New York's Catskill Park. Here, the state's constitution says that land owned by the state must be kept "forever wild." This is part of New York's Forest Preserve.

Most of the forests in the watershed are deciduous trees, which lose their leaves in the fall. These make up almost three-quarters of the total land cover. These woodlands are mostly beech, birch, and maple trees, common in the Catskills. The next largest amount is coniferous forest (trees with needles and cones) at 14 percent. This includes spruce and fir trees that grow on the higher mountain tops.

Water covers about 21 acres (8.5 hectares) of the watershed. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has found 79 separate wetlands within the West Kill watershed, totaling about 128.7 acres (52.1 hectares). Wetlands are areas where the land is covered by water, like marshes and swamps. Only about 7 acres (2.8 hectares) of the basin are covered with hard surfaces like roads.

After open space, most of the remaining land in the watershed is used for low-density homes or is empty land. Farming, mostly raising livestock, makes up 2.6 percent of the land use.

History of the West Kill Valley

Before Europeans came, Native American groups like the Iroquois might have explored the West Kill valley. However, there is no proof they settled there. They preferred richer soils closer to rivers for farming. If they came to the Catskills, it was for travel, hunting, or religious ceremonies.

Even when Europeans arrived, settlers did not immediately move to the West Kill valley. Land lines were drawn in 1708 as part of the Hardenburgh Patent, which was a large land grant. But there is no record of anyone living in the area of modern-day Lexington before the American Revolution.

The first known settler in Lexington was a man named Dryer. In 1780, he used the West Kill's water power to run a factory that made wool. Other settlers also moved into the hamlet of West Kill around the same time. More people followed, attracted by the chance to find furs and timber on cheap land. In 1813, Lexington became its own town, separate from Woodstock.

By the 1820s, the Catskills became home to many small tanneries. These factories used the bark of Eastern hemlock trees to make tannin, which was used to turn animal hides into leather. Hides from all over the Americas were sent to Greene County to be tanned. In 1821, a tannery opened on the West Kill in the area of today's hamlet, helping the community grow. It was far away, but it had access to the river's water and lots of tree bark.

Another tannery opened on the West Kill in 1830, about two miles (3.2 km) above the hamlet. In the same year, a group of Baptist church members in Lexington left to form their own church in West Kill. Three years later, a post office was set up in the hamlet. This shows how the upper West Kill valley had grown in population.

By the mid-1800s, tanneries started to close because there wasn't enough hemlock bark left. After the American Civil War, only a few were left. The owners of boarding houses, which had housed tannery workers, started turning them into summer resorts. They offered a quieter vacation than more popular places.

In 1867, records show that several of these resorts existed, even as far up the West Kill as Spruceton. However, the area's population went down in the late 1800s. This was not only because of lost tannery jobs but also because farming the land was difficult.

Just before the 1900s, a part of the state constitution (Article 14 of 1894) was created. It said that all state land in the Catskill Park (which started in 1904) must stay "forever wild." This rule limited building in the West Kill watershed. Because of this protection, New York City built the Schoharie Reservoir in the mid-1920s to provide water for its growing population.

In the later 1900s, things changed a bit. Hikers started visiting Diamond Notch Falls and climbing the mountains around the valley. As some older farmers stopped farming, their land was divided into large lots for weekend and summer homes. In 2017, West Kill Brewing, a small brewery, opened near the start of the Spruceton Valley. It uses local ingredients and water from the nearby streams.

How the West Kill River Works (Hydrology)

The West Kill watershed gets a lot of rain and snow, about 45.2 inches (1,150 mm) each year. This makes it one of the wettest areas in the Catskills. Most of the water comes from summer thunderstorms or from the leftover storms of hurricanes later in the year. Rain falling on snow in the spring is also a big source of water. The northern slopes of the mountains in the Spruceton Valley don't get much direct sunlight, so they keep large amounts of snow late into the spring.

This pattern of rain and snow, combined with the steep slopes of the West Kill watershed, causes flashiness. This means the river and its smaller streams can rise and fall very quickly after storms. The forests covering much of the watershed help to slow this down a bit, but less so on the north side of the valley where there is less dense plant growth.

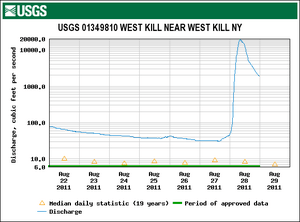

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) has two stations that measure the flow of the West Kill. One is on the lower part of the river, about 1.4 miles (2.3 km) north of the hamlet of West Kill. The other is near the river's source, at the last crossing of Spruceton Road.

In 2016, the lower station reported an average flow of 41.7 cubic feet (1.18 m3) per second. At Spruceton, the average flow was 10.1 cubic feet (0.29 m3) per second. Both stations recorded their highest flows ever on August 28, 2011, when Hurricane Irene passed through the area. At the West Kill station, the river was flowing at 19,100 cubic feet (540 m3) per second!

Water Quality of the West Kill

Because the West Kill is part of New York City's water system, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) checks its water quality. They have found that the water is generally very clean.

The water quality is good for fish and for people to enjoy activities like swimming (though not for drinking directly from the river). The amount of dissolved oxygen in the water is high, which is good for trout. Levels of bacteria like Fecal coliform are very low, much less than what is considered safe for drinking water. Other chemicals like Phosphorus and sulfate are also low. The water's pH level is also healthy for the environment. The water temperature of the West Kill stays between 6 and 10 degrees Celsius (43–50 °F) each year. This is because the forests around its source provide a lot of shade.

However, the West Kill's turbidity levels, which means how cloudy the water is, can be a bit high. This can make the water downstream in the reservoir cloudy. This might happen because the riverbed has been disturbed or because there aren't enough plants along the riverbanks to hold the soil. When the river flows fast, it can stir up fine silts and clays from the riverbed, making the water cloudy.

Controlling Floods in the West Kill

Before Hurricane Irene in 2011, there had been other big floods in the West Kill. For example, in 1927, a flood washed away every bridge in the valley. Another big flood happened after a lot of snow melted quickly in the January 1996 blizzard.

In 2005, the Greene County Soil and Water Conservation District and the DEP created a plan to manage the West Kill. They divided the river into 21 sections and studied each one in detail. They looked for problems that could cause floods or harm animal habitats and suggested ways to fix them.

The areas most at risk for flooding were around the hamlet of West Kill and further downstream. In these places, the river channel gets wider, and floods have changed its path a lot in the past. This leaves wide sand and gravel bars on both sides and in the middle of the river. As a result, the area that floods during a 100-year flood (a very large flood that has a 1% chance of happening in any given year) is wider here.

The plan noted that while some parts of the riverbanks have been reinforced with rocks, the plants along the river are often missing. In some areas, lawns from nearby properties are mowed right up to the riverbanks. Japanese knotweed, a plant that can take over and push out helpful native plants, was found in several places. The plan suggested trying to get rid of this plant throughout the entire watershed.

In 2014, the town's Flood Commission hired an engineering company to study the river between the hamlets of West Kill and Lexington. After running computer tests of floods, they decided that the best solution was to replace the lowest bridge over the West Kill on Route 42.

The old bridge was at a 45-degree angle and not high enough, which blocked the river flow during big floods. The new bridge was designed to be a foot higher. This extra height allows more water to flow under it during floods, which helps lower flood levels upstream and protects homes and businesses. In 2017, the bridge was replaced at a cost of $4.1 million.

Fishing in the West Kill

Art Flick, a famous fly fishing author, lived in Lexington and ran the West Kill Tavern until he passed away in 1985. He hosted many anglers, including some famous people, at his family's tavern. When he wasn't fishing or writing, he worked to protect the streams.

Even though some people are advised to avoid the lower West Kill due to water cloudiness, the DEC still stocks these waters with 700 young brown trout every year. These fish add to the river's natural population. Wild rainbow trout are also found closer to the Schoharie Creek, and brook trout are more common in the Spruceton Valley.

To help people fish, the DEC has bought public fishing rights from landowners along the river. This means people can access certain parts of the river for fishing. There are also small parking lots available for anglers, and much of the stream in the Spruceton area is open to the public.

Images for kids