Wilhelm Busch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wilhelm Busch

|

|

|---|---|

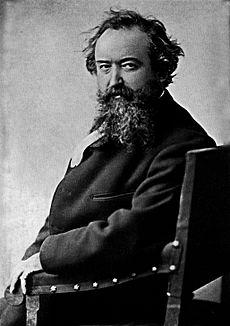

Self-portrait, 1894

|

|

| Born | Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch 14 April 1832 Wiedensahl, Kingdom of Hanover (today Lower Saxony) |

| Died | 9 January 1908 (aged 75) Mechtshausen, Province of Hanover, German Empire (today part of Seesen, Lower Saxony) |

| Education | Hannover Polytechnic, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Beaux-Arts Academy, Antwerp, Academy of Fine Arts, Munich |

| Genre | Caricature, painting, poetry |

| Notable works | Max and Moritz |

| Signature | |

Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch (born April 14, 1832 – died January 9, 1908) was a German humorist, poet, artist, and painter. He created very new and exciting illustrated stories that are still popular today.

Busch used funny folk tales and his deep knowledge of German books and art. He made fun of everyday life, especially people who were too serious or pretended to be very good. He also joked about religious rules and people who were narrow-minded.

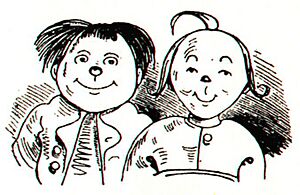

His amazing drawings and poems greatly influenced future generations of comic artists and poets. For example, the famous comic The Katzenjammer Kids was inspired by Busch's story Max and Moritz. Today, the Wilhelm Busch Prize and the Wilhelm Busch Museum help keep his memory alive. Germany celebrated the 175th anniversary of his birth in 2007. Wilhelm Busch is still one of the most important poets and artists in Western Europe.

Contents

Wilhelm Busch's Early Life and Family

Wilhelm Busch's grandfather, Johann Georg Kleine, moved to the small village of Wiedensahl. In 1817, he bought a house there. This was the house where Wilhelm Busch would be born 15 years later. Wilhelm's grandmother, Amalie Kleine, ran a shop. His mother, Henriette, helped her while her two brothers went to high school. When Johann Georg Kleine passed away in 1820, his wife and Henriette continued to run the shop.

Henriette Kleine married a surgeon named Friedrich Wilhelm Stümpe when she was 19. She became a widow at 26, and her three children from Stümpe died as babies. Around 1830, Friedrich Wilhelm Busch, who was a farmer's son, came to Wiedensahl. He had finished a business apprenticeship nearby. He took over the Kleine shop and made it much more modern. He then married Henriette Kleine Stümpe.

Wilhelm's Childhood Years

Wilhelm Busch was born on April 14, 1832. He was the first of seven children born to Henriette Kleine Stümpe and Friedrich Wilhelm Busch. His six younger brothers and sisters were Fanny (1834), Gustav (1836), Adolf (1838), Otto (1841), Anna (1843), and Hermann (1845). All of them lived past childhood. His parents were hard-working and religious Protestants. Even though they became quite wealthy later, they could not afford to send all three sons to school.

Young Wilhelm Busch was a tall child and quite delicate. He was not like the rough, mischievous boys in his later stories, like "Max and Moritz". He described himself as sensitive and shy in his writings. He said he "carefully studied fear" and felt fascinated, sad, and upset when animals were killed in the autumn. He found the "transformation to sausage" "dreadfully compelling," and it stayed with him. He felt sick from pork for the rest of his life.

In the autumn of 1841, after his brother Otto was born, Wilhelm's education was given to his uncle, Georg Kleine. Georg was a 35-year-old clergyman in Ebergötzen. About 100 children were taught in a small space there. This was probably because the Busch family home was too small. His father also wanted a better education for Wilhelm than the local school could offer. The closest good school was in Bückeburg, about 20 km (12 mi) from Wiedensahl. Uncle Kleine and his wife, Fanny Petri, lived in a rectory in Ebergötzen. Wilhelm stayed with another family. His uncle and aunt were caring and responsible. They acted like parents to him and gave him a safe place to stay later in life when things were tough.

Wilhelm's uncle also gave private lessons to Erich Bachmann, the son of a rich miller in Ebergötzen. Wilhelm and Erich became good friends. Busch later said it was the strongest friendship of his childhood. This friendship was shown in his 1865 story, Max and Moritz. A small drawing by the 14-year-old Busch shows Bachmann as a chubby, confident boy, similar to Max. Busch drew himself with a "cowlick," like the "Moritzian" perky style later on.

Uncle Kleine was a philologist, someone who studies language and literature. His lessons were not in modern language. We don't know exactly what subjects Busch and his friend learned. Busch did learn basic math from his uncle. Science lessons might have been more complete because Kleine was a beekeeper, like many other clergymen. He even published essays and books about bees. Busch showed his knowledge of beekeeping in his future stories. Drawing, German, and English poetry were also taught by Kleine.

Wilhelm didn't see his parents much during this time. The 165 km (103 mi) journey between Wiedensahl and Ebergötzen took three days by horse. His father visited Ebergötzen two or three times a year. His mother stayed in Wiedensahl to care for the other children. When 12-year-old Wilhelm visited his family once, his mother didn't recognize him at first. Some people who wrote about Busch think that this early time away from his parents, especially his mother, led to him staying single his whole life. In the autumn of 1846, Busch moved with the Kleines to Lüthorst. There, on April 11, 1847, he was confirmed in the church.

Wilhelm's Studies and Artistic Path

In September 1847, Busch began studying mechanical engineering at Hannover Polytechnic. People who wrote about Busch disagree on why his education in Hanover ended. Most believe his father didn't appreciate his son's artistic talent. One writer, Eva Weissweiler, thinks Uncle Kleine played a big part. Other reasons might have been Busch's friendship with an innkeeper, political talks in the tavern, and Busch's doubts about believing every word of the Bible.

Busch studied for almost four years in Hanover, even though he found the subjects difficult at first. A few months before he was supposed to graduate, he told his parents he wanted to study at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. According to Busch's nephew, Hermann Nöldeke, his mother supported this idea. His father finally agreed, and Busch moved to Düsseldorf in June 1851. He was disappointed not to be accepted into the advanced class, so he started in the beginner classes. Busch's parents paid for his tuition for one year. In May 1852, he traveled to Antwerp to continue his studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. He told his parents that this academy was less strict than Düsseldorf. He also had the chance to study Old Master paintings there. In Antwerp, he saw paintings by famous artists like Peter Paul Rubens for the first time. These pictures made him interested but also made him doubt his own skills. Finally, in 1853, after getting very sick with typhus, he stopped his studies in Antwerp and returned to Wiedensahl with no money.

Munich and Artistic Connections

Busch was very ill, and for five months, he spent his time painting and collecting folk tales, legends, songs, and rhymes. Joseph Kraus, who wrote about Busch, thought these collections were good additions to folklore. Busch wrote down the stories behind the tales and the unique ways storytellers spoke. Busch tried to publish these collections, but he couldn't find a publisher at the time. They were released after he passed away.

After spending six months with his uncle Kleine in Lüthorst, Busch wanted to continue studying in Munich. This request caused a disagreement with his father. However, his father eventually paid for him to move there. Busch's hopes for the Munich Academy of Fine Arts were not met. His life became without a clear goal. He visited Lüthorst sometimes, but he had lost touch with his parents. In 1857 and 1858, when his future seemed uncertain, he thought about moving to Brazil to keep bees.

Busch connected with an artist group called Jung München (Young Munich). He met several important Munich artists and wrote and drew cartoons for the Jung München newspaper. Kaspar Braun, who published funny newspapers like Münchener Bilderbogen (Picture Sheets from Munich) and Fliegende Blätter (Flying Leaves), suggested working with Busch. This partnership gave Busch enough money to live. A drawing he made of himself suggests he had a strong relationship with a woman from Ammerland at this time. His relationship with Anna Richter, a 17-year-old merchant's daughter he met through his brother Gustav, ended in 1862. Busch's biographer, Diers, thinks Anna's father probably didn't want his daughter to marry an almost unknown artist with no steady income.

In his early years in Munich, Busch tried to write librettos (the words for operas), but they were not successful and are mostly forgotten today. Until 1863, he worked on two or three major works. The third one was set to music by composer Georg Kremplsetzer. Busch's Liebestreu und Grausamkeit, a romantic opera, Hansel und Gretel, and Der Vetter auf Besuch, a funny opera, were not very successful. There was a disagreement between Busch and Kremplsetzer during the staging of Der Vetter auf Besuch. This led to Busch's name being removed from the production, and the piece was renamed Singspiel von Georg Kremplsetzer. However, German composer Elsa Laura Wolzogen later set some of his poems to music.

In 1873, Busch returned to Munich several times. He took part in the busy life of the Munich Art Society to escape his quiet life in the countryside. In 1877, in a final attempt to be a serious artist, he got a studio in Munich. He left Munich suddenly in 1881.

The Success of Max and Moritz

Between 1860 and 1863, Busch wrote over a hundred articles for Münchener Bilderbogen and Fliegende Blätter. But he felt too dependent on his publisher, Kaspar Braun. Busch chose Heinrich Richter, a publisher from Dresden, as his new publisher. Richter's company had been publishing children's books and religious books. Busch could choose his own themes. However, Richter had some concerns about four of Busch's suggested illustrated stories. Some of them were published in 1864 as Bilderpossen, but they didn't sell well. Busch then offered Richter the stories of Max and Moritz without asking for any money. Richter turned down the stories because he thought they wouldn't sell well. Busch's old publisher, Braun, bought the rights to Max and Moritz for 1,000 gulden. This was about twice a craftsman's yearly salary at the time.

For Braun, the story turned out to be very lucky. At first, sales of Max and Moritz were slow. But sales improved after the second edition in 1868. By the time Busch died in 1908, there had been 56 editions, and over 430,000 copies were sold. Even though critics ignored it at first, teachers in the 1870s called Max and Moritz silly and a bad influence on young people's morals.

Life in Frankfurt and Later Years

Busch's growing financial success allowed him to visit Wiedensahl more often. He decided to leave Munich because few relatives lived there, and the artist group had temporarily broken up. In June 1867, Busch met his brother Otto for the first time in Frankfurt. Otto was working as a tutor for the family of a rich banker and industrialist named Kessler. Busch became friends with Kessler's wife, Johanna. She was a mother of seven and an important supporter of art and music in Frankfurt. She often held gatherings at her home, where artists, musicians, and philosophers met. She believed Busch was a great painter. While she didn't like his funny drawings, she supported his painting career. She first set up an apartment and studio for Busch in her home, then later gave him an apartment nearby. With Kessler's support and his introduction to Frankfurt's cultural life, Busch's years in Frankfurt were his most artistically productive. During this time, he and Otto discovered the philosophical writings of Arthur Schopenhauer.

Busch did not stay in Frankfurt. Towards the end of the 1860s, he spent time between Wiedensahl and Lüthorst. He also visited Wolfenbüttel, where his brother Gustav lived. His friendship with Johanna Kessler lasted five years. After he returned to Wiedensahl in 1872, they wrote letters to each other. This contact stopped between 1877 and 1891, but then started again with the help of Kessler's daughters.

Busch's Final Years

Dutch writer Marie Anderson wrote letters to Busch. They exchanged over fifty letters between January and October 1875. They talked about philosophy, religion, and ethics. Only one of Anderson's letters still exists, but Busch's letters are preserved. They met in Mainz in October 1875. After that, he returned to Basserman at Heidelback in a "horrible mood." Some people at the time thought Busch's failure to find a wife was why he acted strangely. There is no proof that Busch had a close relationship with any woman after Marie Anderson.

Busch lived with his sister Fanny's family after her husband, Pastor Hermann Nöldeke, passed away in 1879. His nephew Adolf Nöldeke remembered that Busch wanted to move back to Wiedensahl with the family. Busch renovated the house, which Fanny looked after, even though Busch was a rich man. He became like a "father" to his three young nephews. However, Fanny would have preferred to live in a city for her sons' education. For Fanny and her three sons, Busch could not replace their happy life before. The years around 1880 were very tiring for Busch, both mentally and emotionally. He would not invite visitors to Wiedensahl. Because of this, Fanny lost touch with her friends in the village. Whenever she questioned his wishes, Busch became very angry. Even his friends like Otto Friedrich Bassermann and Franz von Lenbach were not welcome at the house. He would meet them in Kassel or Hanover.

Busch stopped painting in 1896. He gave all his publishing rights to Bassermann Verlag for 50,000 gold marks. Busch, who was 64, felt old. He needed glasses for writing and painting, and his hands shook a little. In 1898, he and his aging sister Fanny Nöldeke agreed to Bassermann's suggestion to move into a large parsonage in Mechtshausen. Busch read biographies, novels, and stories in German, English, and French. He organized his works and wrote letters and poems. Most of the poems from the collections Schein und Sein and Zu guter Letzt were written in 1899. The following years were quiet for Busch.

He developed a sore throat in early January 1908, and his doctor found he had a weak heart. During the night of January 8–9, 1908, Busch slept restlessly and took camphor. Busch passed away the next morning before his doctor, called by Otto Nöldeke, could arrive.

Wilhelm Busch's Famous Works

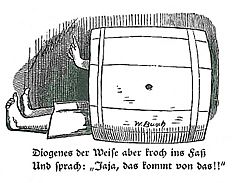

During his time in Frankfurt, Busch published three illustrated stories that made fun of things. Their themes, which were against the church, were popular during the Kulturkampf (a conflict between the German government and the Catholic Church). Busch's satires usually didn't talk about politics. Instead, they exaggerated church rules, superstitions, and people's double standards. This exaggeration made at least two of his works historically inaccurate. The third illustrated satire, Father Filucius, which Busch called an "allegorical mayfly", had more historical meaning.

The Mischievous Max and Moritz

Max and Moritz is a series of seven illustrated stories. It's about the naughty tricks of two boys. In the end, they are ground up and fed to ducks!

Saint Antonius of Padua and Helen Who Couldn't Help It

In Saint Antonius of Padua (Der Heilige Antonius von Padua), Busch questioned Catholic beliefs. It was released when Pope Pius IX declared the dogma of papal infallibility (the belief that the Pope cannot make mistakes in matters of faith). Protestants strongly criticized this idea. The publisher's works were closely watched and censored. The state's attorney in Offenburg accused the publisher, Schauenburg, of "insulting religion and offending public decency." This decision affected Busch. A scene where Antonius, with a pig, is allowed into heaven was seen as controversial. The court in Düsseldorf later banned Saint Antonius. Schauenburg was found not guilty on March 27, 1871, but in Austria, the story was banned until 1902. Schauenburg refused to publish any more of Busch's satires to avoid future problems.

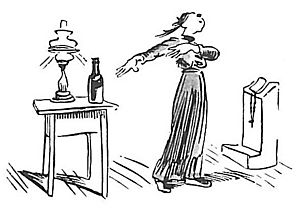

Busch's next work, Helen Who Couldn't Help It (Die fromme Helene), was published by Otto Friedrich Bassermann, a friend Busch met in Munich. Helen Who Couldn't Help It was soon translated into other European languages. It made fun of religious hypocrisy and questionable morals:

|

Ein guter Mensch gibt gerne acht, |

A good person likes to watch, |

Many parts of Helen Who Couldn't Help It criticized the way the Kesslers lived. Johanna Kessler was married to a much older man. She left her children with nannies and tutors while she was very active in Frankfurt's social life.

|

Schweigen will ich vom Theater |

I won't talk about the theater, |

The character of Mr. Schmock, whose name comes from a Yiddish word meaning "fool", was similar to Johanna Kessler's husband. He wasn't interested in art or culture.

In the second part of Helen Who Couldn't Help It, Busch criticized Catholic pilgrimages. Helen, who had no children, went on a pilgrimage with her cousin and a Catholic priest named Franz. The pilgrimage was successful, as Helen later gave birth to twins who looked like Helen and Franz. Franz was later killed by a jealous servant, Jean, because Franz was interested in the female kitchen staff. The now widowed Helen was left with only a rosary and prayer book. She fell into a burning oil lamp. Finally, a character named Nolte says a moral phrase, reflecting the ideas of Schopenhauer:

|

Das Gute — dieser Satz steht fest — |

The good—this rule is clear— |

Pater Filucius (Father Filucius) was the only illustrated satire from this time suggested by the publisher. It was also aimed at people who disliked Catholics and criticized the Jesuit Order. Joseph Kraus felt it was the weakest of the three anti-church works. Some satires referred to events of the time, such as Monsieur Jacques à Paris during the Siege of 1870. Busch biographer Manuela Diers called this story "tasteless work." It used anti-French feelings and made fun of the suffering of French people in Paris, which was occupied by Prussian troops. It shows a French citizen who becomes more and more desperate. First, he eats a mouse during the German siege. Then, he cuts off his dog's tail to cook it. Finally, he invents an explosion pill that kills his dog and two other people. Eva Weissweiler believes Busch wrote this with irony. In Eginhard and Emma (1864), a fictional family story set in the time of Charlemagne, he criticized the Holy Roman Empire. He called for a German empire to take its place. In The Birthday or the Particularists, he made fun of the anti-Prussian feelings of his Hanover countrymen.

Critique of the Heart and Adventures of a Bachelor

Busch stopped writing illustrated tales for a while. He focused on his serious literary work, Kritik des Herzens (Critique of the Heart). He wanted his readers to see him as a more serious artist. Most people at the time didn't like this collection of 81 poems. His long-time friend Paul Lindau called them "very serious, heartfelt, charming poems." Dutch writer Marie Anderson was one of the few who enjoyed Kritik des Herzens. She even planned to publish it in a Dutch newspaper.

Despite a break after moving from Frankfurt, the 1870s were one of Busch's most productive times. In 1874, he created the short illustrated tale, Diddle-Boom! (Dideldum!).

In 1875, the Knopp Trilogy followed, about the life of Tobias Knopp. It included Adventures of a Bachelor (Abenteuer eines Junggesellen), Mr. and Mrs. Knopp (Herr und Frau Knopp) (1876), and "Julie" (Julchen) (1877). The main characters in this trilogy are not mischievous pairs like Max and Moritz. Without being overly emotional, Busch makes Knopp realize that he will not live forever:

|

Rosen, Tanten, Basen, Nelken |

Roses, aunts, cousins, carnations, |

In the first part of the trilogy, Knopp is sad and wants to find a wife. He visits his old friends and their wives. He finds them in difficult relationships. Still not sure if being single is for him, he goes home. Without thinking much, he proposes to his housekeeper. According to Busch's biographer Joseph Kraus, this marriage proposal is one of the shortest in German literature:

|

"Mädchen", spricht er, "sag mir ob..." |

"Girl," he says, "tell me if..." |

According to Wessling, Busch became doubtful about marriage after writing this story. He wrote to Marie Anderson: "I will never marry... I am already in good hands with my sister."

Busch's Last Published Works

Among Busch's last works were the stories Clement Dove, the Poet Thwarted (Balduin Bählamm, der verhinderte Dichter) (1883) and Painter Squirtle (Maler Klecksel) (1884). Both of these stories focus on artistic failure, and indirectly, his own feelings of failure. Both stories begin with an introduction. For biographer Joseph Kraus, these were brilliant examples of "Komische Lyrik"—German comic poetry. Clement Dove made fun of a group of amateur poets in Munich called "The Crocodiles." Painter Squirtle criticized art lovers who believed that the value of art was based on its price.

|

Mit scharfen Blick nach Kennerweise |

With a sharp eye, like an expert, |

The prose play Edwards Dream (Eduards Traum) was released in 1891. It was made up of several small groups of episodes, rather than one continuous story. The work received mixed reviews. Joseph Kraus felt it was the best of Busch's life works. His nephews called it a masterpiece of world literature. The publisher of a special edition said it had a storytelling style not found in other books at the time. Eva Weissweiler saw the play as Busch's attempt to prove himself in the novella style. She believed that everything that angered or insulted him, and his deep emotions, were clear in the story. The 1895 story The Butterfly (Der Schmetterling) made fun of themes and ideas. It also ridiculed the religious optimism of German romanticism, which went against Busch's realistic view of humans, influenced by Schopenhauer and Charles Darwin. Its writing style is more direct than Edwards Dream. Both were not popular with readers because of their unusual style.

Wilhelm Busch's Painting Style

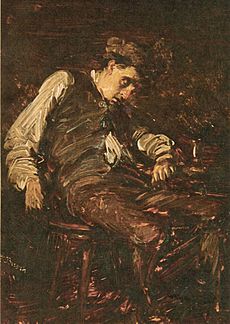

Busch felt his painting skills couldn't compare to those of the Dutch masters. He thought few of his paintings were truly finished. He often stacked them in damp corners of his studio, where they would stick together. If the pile got too high, he would burn some in his garden. Since only a few of his remaining paintings have dates, it's hard to put them in order. His doubts about his skills are shown in the materials he chose. He usually picked his ground (the base layer) carelessly. Sometimes he used uneven cardboard or poorly prepared spruce-wood boards. One exception is a portrait of Johanna Kessler, painted on a canvas that was 63 cm (25 in) by 53 cm (21 in), one of his largest paintings. Most of his works, even landscapes, are small. Because Busch used poor grounds and colors, most of his paintings have become very dark and look almost like one color.

Many pictures show the countryside around Wiedensahl and Lüthorst. They include pollarded willow trees, small houses in cornfields, cowherds, autumn scenes, and meadows with streams. A special feature is his use of red jackets. These are found in about 280 of Busch's 1000 paintings and drawings. The dull or bright red coats are usually worn by a small figure, seen from behind. The paintings generally show typical villages. Portraits of the Kesslers and a series of other portraits of Lina Weissenborn in the mid-1870s are exceptions. A painting of a 10-year-old girl from a Jewish family in Lüthorst shows her as serious, with dark, "oriental" features.

The influence of Dutch painters is very clear in Busch's work. "Hals diluted and shortened... but still Halsian," wrote Paul Klee after visiting a Busch exhibition in 1908. Adriaen Brouwer was a strong influence on Busch. Brouwer's paintings showed farm life and inn scenes, country dances, card players, smokers, and rowdy people. Busch didn't like the techniques of Impressionism, which focused a lot on light effects. He used new colors, like Aniline Yellow, and photographs as a guide. The landscapes from the mid-1880s show the same wide brushstrokes as seen in the paintings of the young Franz von Lenbach. Busch refused to show his work, even though he was friends with many artists from the Munich School who could have helped him. It wasn't until near the end of his life that he showed his paintings to the public.

Wilhelm Busch's Techniques and Style

Joseph Kraus, who wrote about Busch, divided his work into three periods. However, he noted that this is a simple way to classify them, as some works might fit into a later or earlier period. All three periods show Busch's interest in German middle-class life. His peasants are shown without much emotion, and village life is often shown as lacking sentiment.

From 1858 to 1865, Busch mainly worked for Fliegenden Blätter and Münchener Bilderbogen.

The period from 1866 to 1884 is known for his major illustrated stories, like Helen Who Couldn't Help It. These stories have different themes from his earlier works. The lives of his characters start well but then fall apart, as in Painter Squirtle, a sensitive person who becomes a pedant (someone who cares too much about small rules). Other stories are about disobedient children or animals, or they make important people or things seem foolish and ridiculous. His early stories followed the pattern of traditional children's books, like Heinrich Hoffmann's Struwwelpeter. These books aimed to teach about the bad results of misbehavior. Busch didn't think his work was very valuable. He once explained to Heinrich Richter: "I see my things for what they are, like Nuremberg trinkets [toys], like Schnurr Pfeiferen [worthless and useless things] whose value is not in their art, but in what the public wants..."

From 1885 until his death in 1908, his work was mostly prose (regular writing) and poems. The 1895 prose text Der Schmetterling (The Butterfly) contains parts of his own life story. Peter's fascination with the witch Lucinde, whom he feels enslaved by, might refer to Johanna Kessler. Peter, like Busch, returns to his birthplace. Its style is similar to the romantic travel stories that Ludwig Tieck created with his 1798 Franz Sternbalds Wanderungen. Busch played with traditional forms, ideas, pictures, literary topics, and ways of telling stories.

Busch's Artistic Techniques

Publisher Kaspar Braun, who ordered Busch's first illustrations, had set up the first workshop in Germany to use wood engraving. This printing method was developed by English artist Thomas Bewick in the late 1700s. It became the most common way to reproduce illustrations for many years. Busch insisted on drawing first, then writing the poems. Surviving early drawings show notes, ideas, and studies of movement and faces.

Then, the drawing was transferred with a pencil onto white-coated panels of hardwood end grain. This was hard work, and the quality of the printing block was very important. Everything that was left white on the block, around Busch's drawn lines, was cut away by skilled engravers. Wood engraving allowed for more detail than woodcuts. Sometimes the result wasn't good enough, so Busch would rework or redo the plates. The wood engraving technique didn't allow for very fine lines. This is why Busch's drawings, especially in his illustrated stories up to the mid-1870s, are drawn with bold lines. This gives his work its special look.

From the mid-1870s, Busch's illustrations were printed using zincography. With this technique, there was no longer a risk that a wood engraver could change the look of his drawings. The original drawings were photographed and transferred onto a light-sensitive zinc plate. This process allowed for clear, freehand ink lines. It was also a much faster printing method. Busch started using zincography with Mr. and Mrs. Knopp.

Busch's Use of Language

The impact of Busch's illustrations is made stronger by his direct poems. They include teasing, jokes, ironic twists, exaggeration, unclear meanings, and surprising rhymes. His language influenced the funny poetry of Erich Kästner, Kurt Tucholsky, Joachim Ringelnatz, and Christian Morgenstern. In his later work, the contrast between funny pictures and seemingly serious text was already seen in his earlier Max and Moritz. For example, Widow Bolte's overly sad dignity, which seems too much for the loss of her chickens:

|

Fließet aus dem Aug', ihr Tränen! |

Flow from my eyes, you tears! |

Many of Busch's couplets (two rhyming lines), which were common sayings at the time, seem to be full of deep wisdom. But in his hands, they become only apparent truths, hypocrisy, or boring sayings. His use of onomatopoeia (words that sound like what they mean) is a special part of his work: "Allez-oop-da" – when Max and Moritz steal fried chickens with a fishing rod down a chimney – "reeker-rawker"; "at the plank from bank to bank"; "rickle-rackle", "hear the millstones grind and crackle"; and "tinkly-clinket" as Eric the cat pulls a chandelier from a ceiling in Helen Who Couldn't Help It. Busch uses names for his characters that describe their personalities. "Studiosus Döppe" (Young Bumbel) doesn't seem very smart. "Sauerbrots" (Sourdough) wouldn't be a cheerful person. And "Förster Knarrtje" (Forester Knarrtje) could hardly be someone who likes to socialize.

Many of his picture stories use poems with a trochee rhythm (stressed, unstressed syllables):

Master Lampel's gentle powers

Failed with rascals such as ours

The strong emphasis on the stressed syllables makes the lines funnier. Busch also uses dactyls (one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables). For example, in his Plisch und Plum, dactyls highlight the overly serious words that teacher Bokelmann uses to teach his students. They create tension in the Sourdough chapter from Adventures of a Bachelor by switching between trochees and dactyls. Busch often matches the form and content in his poems. In Fips the Monkey, he uses the epic hexameter (a line of verse with six metrical feet) in a speech about wisdom.

In both his illustrations and poems, Busch uses familiar fables. Sometimes he takes their morals and stories, twisting them to show a very different and funny "truth." He uses these to express his often pessimistic view of the world and human nature. While traditional fables usually show a clear difference between good and bad behavior, Busch combines both.

Wilhelm Busch's Legacy and Influence

Busch celebrated his 70th birthday at his nephew's house in Hattorf am Harz. More than 1,000 congratulatory messages were sent to Mechtshausen from all over the world. Wilhelm II praised the poet and artist, saying his "excellent works are full of true humor and are timeless for the German people." The Austrian Pan-German Association lifted the ban on Der heilige Antonius von Padua. Verlag Braun & Schneider, who owned the rights to Max and Moritz, gave Busch 20,000 ℛℳ (about €200,000 or $270,000 today). This money was donated to two hospitals in Hanover.

Since then, on the anniversaries of his birth and death, he has been celebrated often. During the 175th anniversary in 2007, many of Busch's works were republished. Deutsche Post (German Post Office) issued stamps showing the Busch character Hans Huckebein. The German Republic also made a 10 Euro silver coin with his portrait. Hanover declared 2007 the "Wilhelm Busch Year," and images of Busch's works were put up on columns in the city center.

The Wilhelm Busch Prize is given out every year for funny and satirical poetry. The Wilhelm Busch Society, active since 1930, aims to "collect, scientifically review, and promote Wilhelm Busch's works to the public." It supports the development of caricature and satirical art as a recognized form of visual art. It also supports the Wilhelm Busch Museum. Memorials are located in places he lived, including Wiedensahl, Ebergötzen, Lüthorst, Mechtshausen, and Hattorf am Harz.

Busch's Influence on Comics

Andreas C. Knigge described Busch as the "first virtuoso" of illustrated stories. From the second half of the 1900s, he was seen as the "Forefather of Comics." His early illustrations were different from those of his colleagues. They focused more on the main characters, had less detail in the background, and developed the story in a dramatic way. All of Busch's illustrated tales have a plot that first describes the situation, then a problem, and then a solution. Stories are told through a series of scenes, similar to film storyboards. Busch creates a feeling of movement and action, sometimes by changing the viewpoint. According to Gert Ueding, his way of showing movement is unique.

One of Busch's notable stories is Der Virtuos (1865). It describes the life of a pianist who plays privately for an excited listener. It makes fun of artists who show off and people who admire them too much. This story is different from Busch's others because each scene doesn't have prose. Instead, it uses music terms like "Introduzione," "Maestoso," and "Fortissimo vivacissimo." As the scenes get faster, every part of the pianist's body and his coat tails move around. The scene before the last one again shows the pianist's movements, with music sheets floating above the grand piano and musical notes dancing. Over the years, artists have been fascinated by Der Virtuos. August Macke, in a letter to gallery owner Herwarth Walden, called Busch the first Futurist. He said Busch captured time and movement very well. Similar groundbreaking scenes are in Bilder zur Jobsiade (1872). Job fails to answer easy questions asked by twelve clergymen, who shake their heads at the same time. Each scene is a study of movement that came before Eadweard Muybridge's photography. Muybridge began his work in 1872, but it wasn't released until 1893.

"Moritzian" Influence on Other Works

Busch's biggest success, both in Germany and worldwide, was Max and Moritz. By the time he died, it had been translated into English, Danish, Hebrew, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Hungarian, Swedish, and Walloonian. Several countries banned the story. Around 1929, the Styrian school board banned sales of Max and Moritz to teens under eighteen. By 1997, over 281 translations into different dialects and languages had been made.

Some early "Moritzian" comic strips were heavily influenced by Busch in their plot and storytelling style. Tootle and Bootle (1896) copied so much from Max and Moritz that it was called a pirated edition. The true "Moritzian" remake is The Katzenjammer Kids by German artist Rudolph Dirks. It was published in the New York Journal starting in 1897. It was published because William Randolph Hearst suggested creating a pair of siblings like "Max and Moritz." The Katzenjammer Kids is considered one of the oldest, continuously running comic strips.

German stories inspired by "Moritzian" themes include Lies und Lene; die Schwestern von Max und Moritz (Hulda Levetzow, F. Maddalena, 1896), Schlumperfritz und Schlamperfranz (1922), Sigismund und Waldemar, des Max und Moritz Zwillingspaar (Walther Günther, 1932), and Mac und Mufti (Thomas Ahlers, Volker Dehs, 1987). These stories were shaped by observations of the First and Second World Wars, while the original is a moral story. In 1958, the Christian Democratic Union used the Max and Moritz characters for a campaign in North Rhine-Westphalia. In the same year, the East German satirical magazine Eulenspiegel used them to make fun of black labor. In 1969, Max and Moritz "participated" in the student activism of the late 1960s.

See also

In Spanish: Wilhelm Busch para niños

In Spanish: Wilhelm Busch para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |