William Ewart Gladstone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Ewart Gladstone

FRS FSS

|

|

|---|---|

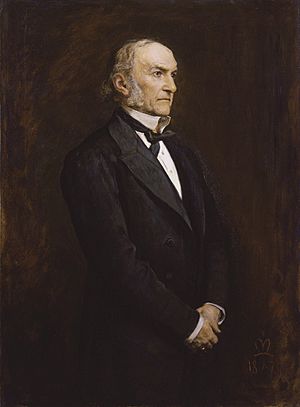

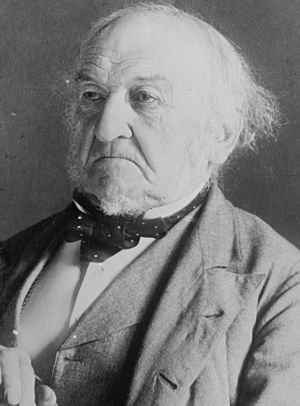

Gladstone in 1892

|

|

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 15 August 1892 – 2 March 1894 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Rosebery |

| In office 1 February 1886 – 21 July 1886 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| In office 23 April 1880 – 9 June 1885 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| In office 3 December 1868 – 17 February 1874 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 28 April 1880 – 16 December 1882 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Stafford Northcote |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Childers |

| In office 11 August 1873 – 17 February 1874 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Robert Lowe |

| Succeeded by | Stafford Northcote |

| In office 18 June 1859 – 26 June 1866 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Palmerston The Earl Russell |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| In office 28 December 1852 – 28 February 1855 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Earl of Aberdeen |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | George Cornewall Lewis |

| Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands | |

| In office 25 January 1859 – 17 February 1859 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Sir John Young |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Knight Storks |

| Additional positions | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 December 1809 62 Rodney Street, Liverpool, Lancashire, England |

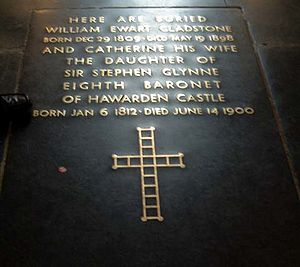

| Died | 19 May 1898 (aged 88) Hawarden Castle, Flintshire, Wales |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Political party | Liberal (1859–1898) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 8; including William, Helen, Henry and Herbert |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

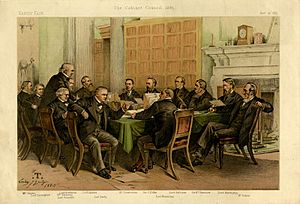

| Cabinet | |

| Signature |  |

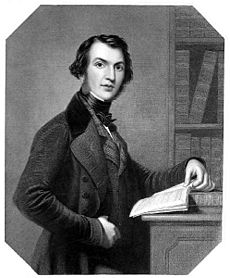

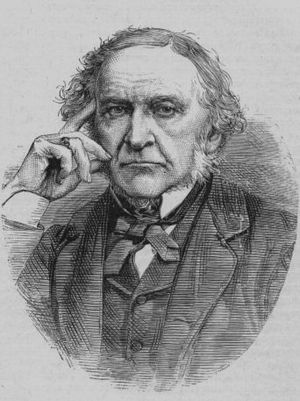

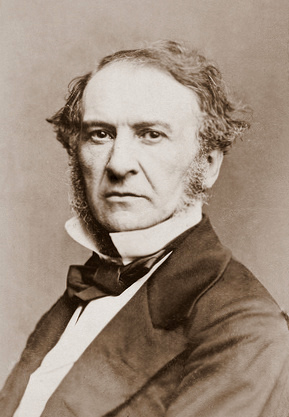

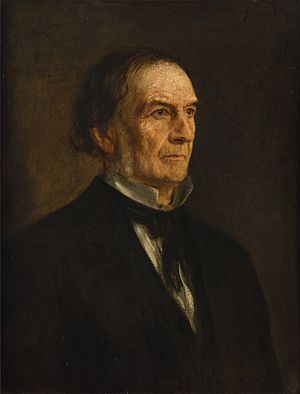

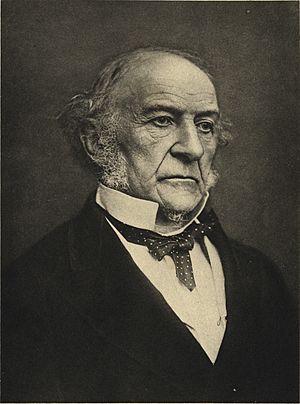

William Ewart Gladstone (born December 29, 1809 – died May 19, 1898) was a very important British politician. He was a member of the Liberal Party. His career in politics lasted over 60 years.

Gladstone served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom four times. This was for a total of 12 years. He was also the Chancellor of the Exchequer (in charge of the country's money) four times. He was known as "The People's William" because he was popular with working-class people. Historians often consider him one of Britain's greatest leaders.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Starting in Parliament

- Working for Robert Peel

- Out of Office and Return

- Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Between Governments

- Back as Chancellor

- First Time as Prime Minister (1868–1874)

- Out of Office (1874–1880)

- Second Time as Prime Minister (1880–1885)

- Third Time as Prime Minister (1886)

- Out of Office Again (1886–1892)

- Fourth Time as Prime Minister (1892–1894)

- Final Years (1894–1898)

- Marriage and Family

- Gladstone's Legacy

- Monuments and Archives

- Images for kids

- Portrayal in Film and Television

- Works

- See also

Early Life and Education

William Ewart Gladstone was born in Liverpool, England, on December 29, 1809. His parents, John Gladstone and Anne MacKenzie Robertson, were from Scotland. His father was a wealthy merchant.

Young William, or "Willy," visited Scotland and London as a child. He saw the Prince Regent at a special service in London. He was educated at Eton College, a famous school. Later, he went to Christ Church, Oxford, a university. He studied Classics and Mathematics. He was very good at speaking and became known as a great orator (speaker).

After university, he traveled around Europe. He thought about becoming a lawyer. However, he decided to focus on politics instead. In 1842, he had an accident while reloading a gun and lost his left forefinger. After that, he always wore a glove or a special cover on his finger.

Starting in Parliament

First Steps in Politics

Gladstone first became a Member of Parliament (MP) in 1832. He was 22 years old. He represented a place called Newark. He started his political career as a High Tory, which was a group that later became the Conservative Party.

Early in his career, Gladstone defended the rights of plantation owners who used enslaved people. His father was one of these owners. However, Gladstone also spoke about the need to pay factory workers more. He voted against a law in 1833 that would have limited the working hours for child workers.

Views on Slavery

Gladstone's early ideas about slavery were influenced by his father, who owned many enslaved people. He believed slavery should end gradually, not immediately. He thought enslaved people should first learn "honest and industrious habits."

In 1834, when slavery was ended across the British Empire, owners were paid for their enslaved people. Gladstone helped his father get a large payment from the government. Later in his life, Gladstone's views on slavery changed. He began to oppose it more strongly. He even broke with his father over a plan to reduce taxes on sugar not produced by enslaved labor. He later said that ending slavery was one of the greatest achievements of his time.

Opposing the Opium Trade

Gladstone strongly opposed the opium trade. This was when Britain sold opium from India to China. He called it "infamous and atrocious." He was a fierce critic of the Opium Wars. These were wars Britain fought to force China to allow the opium trade. Gladstone said he feared "the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China."

Working for Robert Peel

Gladstone was re-elected to Parliament in 1841. He served in the government of Prime Minister Robert Peel. He was in charge of trade from 1843 to 1845.

He helped create the Railways Act of 1844. This law was important for regulating railways, which were a huge new industry. It even included rules for cheap "Parliamentary trains" and government control of railways during wartime.

Gladstone also helped "coal whippers," who were men who unloaded coal from ships. These workers were often forced to pay publicans (pub owners) to get jobs. Gladstone passed a law in 1843 to create a central office for employment. This helped stop the unfair system. He later called this law "the most Socialistic measure of the last half century."

He resigned from Peel's government in 1845. This was because of a disagreement about giving money to a Catholic seminary in Ireland. Gladstone had written a book saying a Protestant country should not fund other churches. Even though he supported the grant, he resigned to stick to his principles.

Out of Office and Return

After Peel's government ended in 1846, Gladstone became a leader of a group called the Peelites. They supported Peel's ideas. He was re-elected as an MP for Oxford University.

In 1850-1851, Gladstone visited Naples, Italy. He was shocked by the way the government treated political prisoners. He wrote letters describing it as "the negation of God erected into a system of government."

Chancellor of the Exchequer

In 1852, Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer (finance minister). He was part of a government led by Lord Aberdeen.

His first budget in 1853 simplified Britain's taxes on imports. He removed or reduced many duties. He wanted to get rid of income tax. To do this, he lowered the income level at which people had to pay it. He believed that if more people paid income tax, they would push the government to spend less.

During the Crimean War (which started in 1854), Gladstone insisted on raising taxes to pay for the war, instead of borrowing money. He believed this would make people feel the cost of war and prevent unnecessary conflicts. He said war expenses were "the moral check...upon the ambition and lust of conquest."

He resigned in 1855 when the government faced questions about how it was handling the war.

Between Governments

From 1858 to 1859, Gladstone worked on a special mission to the Ionian Islands, which were under British protection.

Around this time, Gladstone started a hobby of felling trees. He continued this until he was 81! People joked that his hobbies, like his politics, were "destructive." But he also planted new trees to replace the ones he cut down.

Gladstone loved books. He read about 20,000 books in his lifetime and owned a library of over 32,000.

Back as Chancellor

In 1859, Gladstone joined a new government led by Lord Palmerston. He became Chancellor of the Exchequer again and joined the new Liberal Party.

He faced a large government debt. He raised income tax to help pay it off. He worked with Richard Cobden to create a free trade treaty with France. This treaty reduced taxes on goods traded between the two countries.

Gladstone's budget in 1860 greatly reduced the number of taxes on imported goods. He believed in "Free Trade," meaning fewer taxes on goods from other countries. To make up for lost tax money, he had to raise income tax.

He also wanted to remove the tax on paper. This tax made books and newspapers more expensive. He believed removing it would help spread ideas. The House of Lords (the upper house of Parliament) tried to stop this, but Gladstone found a way to pass the law. This was a big win for the freedom of the press.

Gladstone gradually lowered income tax during his time as Chancellor. He believed the government should spend less money and let people keep more of their earnings. He was known as the "liberator of British trade" and was very popular with working people.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War, Gladstone believed the Southern states would win their independence. He thought the North was wrong to try to force the Union back together. However, he also disliked slavery. His comments caused some confusion, as people thought Britain might recognize the Confederacy.

Voting Reform

Gladstone started to support giving more working-class men the right to vote. This was a change from his earlier views. This idea caused some disagreement with Lord Palmerston, who was against it.

In 1865, Gladstone lost his seat representing Oxford University. This was because his support for voting reform and changes to the Church of Ireland upset some of his voters. However, he was quickly elected as an MP for South Lancashire. He famously said he was now "unmuzzled," meaning he could speak more freely.

After Palmerston died, Gladstone became the senior Liberal in the House of Commons. He tried to pass a new voting reform bill, but it failed. Later, his rival, Benjamin Disraeli, passed a similar bill. This made Gladstone very angry and started a long rivalry between them.

Leader of the Liberal Party

In 1867, Gladstone became the leader of the Liberal Party. In 1868, he proposed changes to the Church of Ireland, which helped unite the Liberal Party. This led to a general election.

First Time as Prime Minister (1868–1874)

In the 1868 election, Gladstone lost his seat in South Lancashire but won in Greenwich. He became Prime Minister for the first time. He famously said his mission was "to pacify Ireland."

During his first time as Prime Minister, many important changes were made:

- The Church of Ireland was no longer the official church in Ireland. This meant Irish Catholics did not have to pay taxes to the Anglican Church.

- The secret ballot was introduced. This meant people could vote in private, without others knowing who they voted for.

- The Forster's Education Act was passed. This created local school boards and aimed to provide education for all children.

- The Trade Union Act made trade unions legal. This allowed workers to organize and fight for their rights.

- The Universities Tests Act allowed people who were not Anglicans to study at Oxford and Cambridge universities.

- Gladstone settled the Alabama Claims with the United States peacefully. This avoided a possible war.

Gladstone unexpectedly called a general election in 1874. His party lost, even though they received more votes overall. This was partly because the Liberal Party's organization had weakened.

Out of Office (1874–1880)

After losing the election, Gladstone stepped down as leader of the Liberal Party. However, he kept his seat in Parliament.

Views on Catholicism

Gladstone had mixed feelings about Catholicism. He admired its traditions but disliked its strong central authority. He was worried when the Pope declared Papal Infallibility in 1870. Gladstone wrote a pamphlet saying this could make British Catholics less loyal to the Queen. The pamphlet sold 150,000 copies.

Bulgarian Horrors

In 1876, Gladstone published a pamphlet called Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East. He criticized the government for not caring about the brutal way the Ottoman Empire treated people during the Bulgarian April uprising. He was very angry about the violence.

During the Midlothian campaign in 1879, Gladstone gave powerful speeches. He spoke against the government's foreign policies, especially the Second Anglo-Afghan War and the Anglo-Zulu War.

Second Time as Prime Minister (1880–1885)

In 1880, the Liberals won the election again. Gladstone became Prime Minister for the second time. He also served as Chancellor of the Exchequer until 1882.

Foreign Policy Decisions

Gladstone generally opposed expanding the British Empire. However, his government made some big decisions in foreign policy.

- The Second Anglo-Afghan War ended.

- The First Boer War was fought.

- In 1882, Gladstone ordered the bombardment of Alexandria in Egypt. This led to a short war and British control of Egypt for many years. This decision was controversial, especially with France.

Dealing with Ireland

In 1881, Gladstone passed the Coercion Act for Ireland. This allowed the government to arrest people without trial to control unrest. He also passed the Second Land Act. This law gave Irish tenant farmers more rights, including fair rent and security of tenure.

Expanding Voting Rights

Gladstone continued to expand voting rights. The 1884 Reform Act gave agricultural workers the right to vote. This added six million more people to the voting lists.

Challenges and Resignation

Gladstone was worried about the direction of politics. He thought both Conservatives and some Liberals were focusing too much on state control rather than individual freedom.

His government faced a major crisis in Sudan. General Gordon's forces were under siege in Khartoum. Gladstone delayed sending help. When the rescue mission arrived in January 1885, it was two days too late. Gordon and many soldiers were killed. This disaster severely damaged Gladstone's popularity. Critics called him the "Murderer of Gordon." He resigned as Prime Minister in June 1885.

Third Time as Prime Minister (1886)

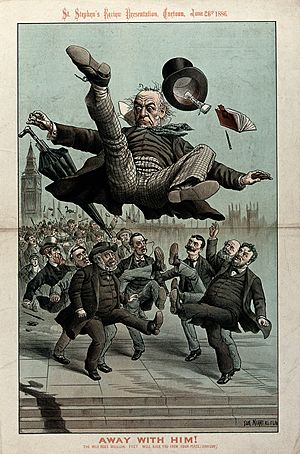

In 1886, Gladstone became Prime Minister for the third time. His main goal was to give Home Rule to Ireland. This meant Ireland would have its own parliament to manage local affairs.

However, this idea split the Liberal Party. Many Liberals, called "Liberal Unionists," opposed Home Rule. The bill was defeated in Parliament. This ended Gladstone's government after only a few months.

Out of Office Again (1886–1892)

Gladstone continued to support workers' rights. He supported the London dockers' strike in 1889. He said that the strike helped strengthen workers against employers. He believed that workers were generally "in the right" in disputes with capital.

He also spoke about the need for society to offer something better than the workhouse (a place for very poor people) to hardworking people in their old age.

Fourth Time as Prime Minister (1892–1894)

In 1892, Gladstone became Prime Minister for the fourth time. He was 82 years old, making him the oldest person to ever become Prime Minister.

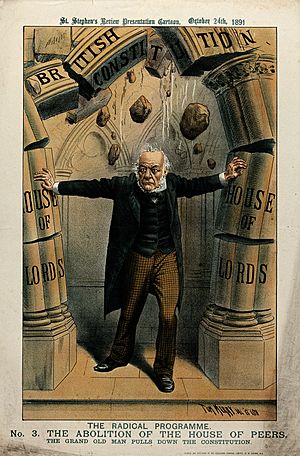

He again introduced a Home Rule Bill for Ireland. It passed in the House of Commons but was defeated by the House of Lords.

His government also passed the Elementary Education (Blind and Deaf Children) Act in 1893. This law required local authorities to provide special education for blind and deaf children.

Gladstone resigned in March 1894. He was 84 years old. He was the only Prime Minister to serve four separate terms. He left Parliament in 1895.

Final Years (1894–1898)

In 1895, Gladstone gave £40,000 and most of his 32,000 books to start St Deiniol's Library in Hawarden, Wales.

In his last years, Gladstone continued to express his views. He worried about the "love of money" and the "dreadful military spirit" in the country. He also spoke out against the massacres of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire.

In 1897, he met Queen Victoria in Cannes. She shook his hand, which he remembered as the first time in 50 years.

Gladstone was diagnosed with cancer in 1898. He returned to Hawarden Castle. He died there on May 19, 1898, at the age of 88. His daughter Helen cared for him.

His funeral was a public event at Westminster Abbey. The future King Edward VII and King George V were pallbearers. He was buried next to his wife, Catherine, who died two years later.

Marriage and Family

Gladstone married Catherine Glynne in 1839. They were married for 59 years. They had eight children together:

- William Henry (Willy)

- Agnes

- Stephen Edward

- Catherine Jessy (who died young)

- Mary

- Helen

- Henry Neville

- Herbert John

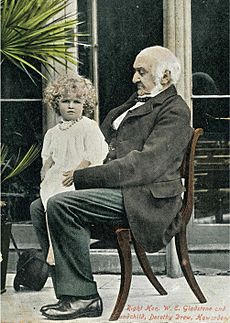

Two of his sons, William Henry and Herbert, became Members of Parliament. His grandson, William Glynne Charles Gladstone, also became an MP.

Gladstone's Legacy

Historians say Gladstone's main impact was in three areas:

- His financial policies, which aimed to keep taxes low and promote free trade.

- His support for Home Rule (giving local power to Ireland).

- His idea of a progressive political party that could bring different groups together.

He was seen as a champion of individual freedom and responsible government spending. Later politicians, including Margaret Thatcher, admired his economic ideas.

Monuments and Archives

Recordings and Writings

- Thomas Edison's agent recorded Gladstone's voice on a phonograph.

- The National Library of Wales has many pamphlets sent to Gladstone. These show what people were concerned about during his time.

Statues and Memorials

Many statues and memorials honor Gladstone across the United Kingdom and beyond:

- A statue at Bow Church in London.

- A statue in St John's Gardens, Liverpool.

- The Gladstone Memorial in Aldwych, London.

- A statue in Albert Square, Manchester.

- A monument in Edinburgh.

- A statue in George Square, Glasgow.

- A bust in the Hall of Heroes at the Wallace Monument in Stirling.

- A statue at Gladstone's Library in Hawarden.

- A statue in Athens, Greece.

- A statue at Glenalmond College.

- A memorial bust in Seaforth, Liverpool, where he went to school.

Places Named After Him

- Gladstone Park in London.

- Gladstone Rock on Snowdon in Wales, where he gave a speech.

- Several towns in the United States (like Gladstone, Oregon) and Australia (Gladstone, Queensland).

- Gladstone, Manitoba, in Canada.

- Many streets in cities around the world, including Athens, Sofia, Liverpool, and Vancouver.

- A hall of residence and a professorship at the University of Liverpool.

- The Gladstone bag, a type of traveling bag, is named after him.

- The Gladstone Theatre in Port Sunlight.

Images for kids

-

Statue at Aldwych, London, near to the Royal Courts of Justice and opposite Australia House

-

Statue in Albert Square, Manchester, Manchester

-

Statue on the Gladstone Monument in Coates Crescent Gardens, Edinburgh

-

A high school named after Gladstone in Sofia, Bulgaria

Portrayal in Film and Television

William Gladstone has been shown in many films and TV shows. Some actors who have played him include:

- Ralph Richardson in the film Khartoum (1966)

- Michael Hordern in the TV series Edward the Seventh (1975)

- John Carlisle in the TV series Disraeli (1978)

Works

- The State in its relations with the Church (1841)

- Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age (1858)

- A Chapter of Autobiography (1868)

- Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East (1876)

- On books and the Housing of them (1890)

See also

In Spanish: William Gladstone para niños

In Spanish: William Gladstone para niños

- Foreign Policy of William Ewart Gladstone

- Liberalism in the United Kingdom