Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit |

| Decided | January 7, 1884 |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Lorenzo Sawyer |

| Keywords | |

| California, Gold Rush, Mining | |

The case of Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company was a big lawsuit in California in 1882. A group of local farmers sued the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company. They claimed the company's mining operations were harming their farms in the Central Valley.

The farmers said that the company's hydraulic mining used a lot of water to find gold. This process dumped too much dirt, rocks, and chemicals into local rivers. This made the riverbeds higher and blocked the water flow, causing huge floods. These floods had already ruined a lot of farms in the valley.

After two years, Judge Lorenzo Sawyer made his decision. He agreed with the farmers. He said that mining waste was dangerous to private land, especially farms. Judge Sawyer's decision limited how much hydraulic mining could happen in California. Many people see this as California's first major environmental law. Today, the biggest mine of the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company, called Malakoff Diggins, is a California State Historic Park near Nevada City.

Contents

California's Gold Rush History

How Gold Was Found in California

The first gold in California was found by James W. Marshall on January 24, 1848. He found it at Sutter's Mill in Coloma. Marshall worked for John Sutter, who started Sutter's Fort. While checking lumber equipment, Marshall saw shiny rocks in the American River. He tested them and found out it was gold.

Sutter tried to keep it a secret, but the news quickly spread to San Francisco. After military officers saw the gold fields, a report went to the United States Congress. Soon, President Polk told the whole country about the discovery. This led to many people from all over the country rushing to California.

Early Gold Mining Methods

Most mining towns in California grew in the foothills of Northern California, close to Sutter's Mill. This area, especially in counties like Sierra and Nevada, had a lot of gold. Many towns stretched from Mariposa in the south to Chico in the north. This whole area was known as the Mother Lode because of the huge amount of gold found there.

At first, gold mining was small and didn't harm the environment much. A common method was panning for gold in the American River. Miners used a shallow pan with water to sift through river gravel. This was simple but slow, and miners didn't find much gold this way. Other tools like rockers and sluice boxes were faster but still slow. They also made it hard to find small gold pieces among bigger rocks.

These early methods were called placer mining. This meant mining for gold found near the surface. But miners wanted to reach larger gold deposits deep inside the Mother Lode.

Hydraulic Mining Explained

How Hydraulic Mining Started

As more miners came, it became harder to find gold with simple methods. The remaining gold was deep inside the hillsides of the Mother Lode. Miners then looked for new ways to get this deeper gold. In 1853, a miner named Edward Matteson in Nevada City found a new way. He used a high-pressure hose to wash away gravel and find gold.

Miners were excited about finding more gold. They worked to get money from rich investors and form companies. Most hydraulic mining sites appeared in northern California's Mother Lode in the 1860s. These areas had the most gold and were close to water sources, which were key for this type of mining.

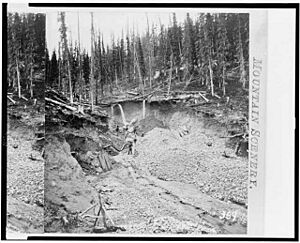

During hydraulic mining, local rivers and streams were sent into narrow channels. These channels funneled water into powerful water cannons called "monitors." The pipes were set up downhill to make the water flow with high pressure. This allowed the water to blast away dirt and rocks from hillsides. These monitors were so strong they could move rocks as big as a car! The huge amounts of rock, minerals, and soil were then sent into sluices. Miners would sift through this material to find valuable gold. However, this process created a lot of waste, called "debris." This debris was usually dumped into tunnels downstream. As the debris flowed, much of it settled in the riverbeds, blocking the water flow.

The biggest mining operation was the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company's Malakoff Mine near Nevada City.

Environmental Problems from Mining

While hydraulic mining was very good at finding gold, it also greatly changed local ecosystems. It harmed the plants, animals, and even the land itself.

Before mining, many trees were cut down. They were either sold for wood or cleared to make space for mining. Other plants and trees were destroyed or polluted during the mining process. This meant local wildlife lost their homes or their homes were damaged. Some animal species had to leave the area, and others almost disappeared. The California grizzly bear was one animal whose numbers dropped a lot. Fish like salmon were also badly affected. Too much debris and dangerous chemicals in the rivers changed the water's pH (how acidic or basic it was) and temperature. This also made it hard for fish to reach the ocean and their spawning (breeding) areas.

The mining debris didn't just affect nearby communities. Rivers in the Sierra Nevada mountains started as small streams. As they flowed downhill, they collected water from rain and melting snow. They grew bigger and faster. These rivers then joined other rivers, like the Sacramento or Yuba, and flowed into the valley. But the mining waste had been dumped downstream and blocked these rivers. This made the riverbeds higher and greatly increased the chance of floods.

While the mountains were safer because they were higher up, the low-lying farms in the valley were very vulnerable. As a result, valley cities were flooded with mud and debris. This destroyed farms and even towns. There were also not many dams or other protections back then. So, the rising water levels ruined farms, property, and even killed people. The financial losses to the valley cities and farming industry were huge.

Different Opinions on Mining

The Anti-Debris Association

After a very bad flood hit Marysville in 1875, people from the Central Valley formed the Anti-Debris Association in 1878. At first, they didn't want to stop hydraulic mining. They just wanted mining companies to be responsible for the waste they created. The farmers argued that their private land rights were violated when mining debris harmed their property.

The Sacramento Record-Union newspaper helped organize the association. The owners of the Southern Pacific Railway also worried about the mining's impact. For several years, the farmers tried to work with state officials and mining companies to find a solution. They sent petitions, but these efforts didn't work. However, the farmers were able to record what they called "environmental negligence" by the mining companies. The farmers also created the Anti-Debris Guard, a group of men who protected the valley. They also pushed for a State Engineering office to check dams and mining operations.

The Hydraulic Miners' Associations

Like the farmers, the Hydraulic Miners' Association was formed to protect their industry. They started their group in 1876 to challenge the Anti-Debris Association. The miners argued that since they legally owned the land they mined, they could do whatever they wanted with it. They also claimed that city growth, not just hydraulic mining, caused the flooding. They believed that floods and environmental damage were unavoidable if progress was to happen. At that time, laws usually favored miners, and there were few rules about industries.

After strong arguments with the Anti-Debris Association, some people thought the Hydraulic Miners' Association might have broken a nearby levee (a wall to hold back water). This would have caused more damage to farms in Yuba County. However, there was no real proof linking the miners to this event.

The Lawsuit Begins

After years of little success, a wheat farmer named Edward Woodruff filed a lawsuit. He sued the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company on behalf of the farmers in the Central Valley. This case became known as Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company.

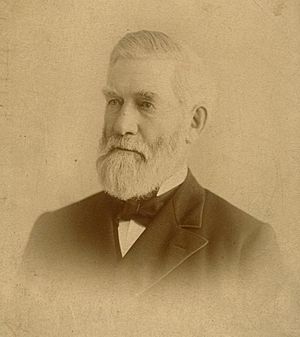

Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, a Ninth Circuit Judge, was assigned the case. He had been a miner himself during the early gold rush. He was known for being fair and thorough. He took two years to investigate the farmers' claims. During the case, Judge Sawyer visited the mining sites many times. He interviewed both farmers and miners. He also looked at the sites and the surrounding nature to understand the full effects of mining.

In court, several people testified against the mining company. This included the Southern Pacific Railway Company. They worried that hydraulic mining would harm their railroad tracks and business. Mining had already made it hard for ships and steamboats to travel in the Sacramento Valley because riverbeds were too high. The wealthy Southern Pacific company had similar concerns.

Woodruff's lawyers used photographs by John Todd in court. Todd's pictures showed the destruction caused by mining. They also showed that North Bloomfield didn't take enough steps to prevent flooding. Because there was strong support for the farmers in the valley, few people testified in the miners' defense, except for the company itself.

After two years, Judge Sawyer announced his decision on January 7, 1884. His decision was 225 pages long. Sawyer concluded that the mining operations were harmful to farmers, state-funded buildings, and the people of California. So, Sawyer ruled that mining companies could no longer dump debris into waterways. This didn't stop hydraulic mining completely, but it greatly limited what the big mining companies could do.

What Happened After the Decision

As you might guess, the farmers and the public were very happy with Judge Sawyer's decision. Records show that church bells in Yuba County even rang after the ruling. However, the miners felt that their industry was unfairly targeted. They believed it was a limit on progress.

After the Sawyer Decision, the Anti-Debris Association continued to work. They helped make sure the rules were followed and pushed for more laws. The North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company kept mining at Malakoff Diggins, but much less than before. In 1886, their operations were found to be breaking the Sawyer Act. Miners were still dumping waste into local waterways. As a result, the company had to pay large fines and change how they operated. This further reduced their profits.

Following Sawyer's work, the Caminetti Law was passed by Congress in 1893. This law further limited mining. It required all hydraulic mining operations to have a license. The North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company chose not to follow this law and was later fined. Because of these strict rules, many smaller mining companies closed down. They moved their businesses to places like Colorado and Alaska, where there were fewer rules. Malakoff Diggins was one of the last hydraulic mining operations until it closed in 1910. It became a California State Historic Park in 1965.

The Legacy of the Decision

Judge Sawyer's decision is often seen as California's first environmental law. While its full impact was debated, it did put rules on industry. It also set an important example for future laws. This law helped California change from a wild gold rush area to a strong farming region, especially for wheat.

The Central Valley was perfect for farming. It had fertile land, low elevations, sunny weather, and rivers for irrigation. This promised more profit than the gold rush. But the mining industry was still a problem. Sawyer understood how the old mining industry could hurt California's new economy. So, he decided that government rules were the best way to protect the rights of farmers from big mining companies.

|

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |