2019 Amazon rainforest wildfires facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 2019 Amazon rainforest wildfires |

|

|---|---|

|

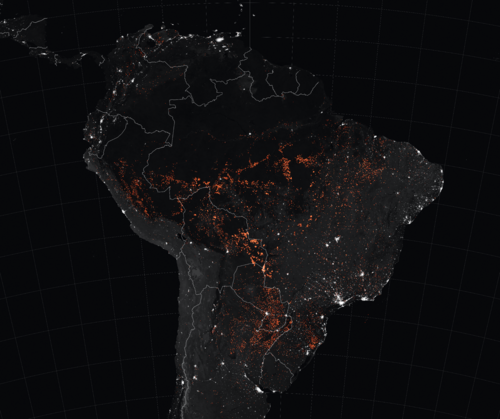

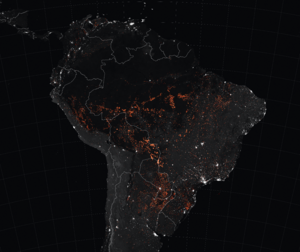

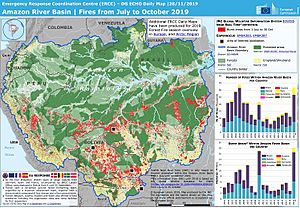

Locations of fires, marked in orange, which were detected by MODIS from August 15 to 22, 2019

|

|

| Location | Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay, Colombia |

| Statistics | |

| Total fires | >40,000 |

| Cost | >$900 billion (2019 USD) |

| Date(s) | January–October 2019 |

| Burned area | 906,000 hectares (2,240,000 acres; 9,060 km2; 3,500 sq mi) |

| Cause | Slash-and-burn approach to deforest land for agriculture and effects of climate change and global warming due to unusually longer dry season and above average temperatures worldwide throughout 2019 |

| Land use | Agricultural development |

| Deaths | 2 |

| Map | |

Amazon rainforest ecoregions as delineated by the WWF in white and the Amazon drainage basin in blue. |

|

The 2019 Amazon rainforest wildfires were a series of large fires that happened in the Amazon rainforest and nearby areas in 2019. These fires mostly affected Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru. Fires often occur during the Amazon's dry season. This is because people use a method called slash-and-burn to clear land. They do this to make space for farms, raising animals, cutting down trees for wood, and mining. This activity leads to deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, which means cutting down forests.

Even though clearing land this way is usually against the law, it's not always stopped. The large number of fires in 2019 worried people around the world. The Amazon rainforest is very important because it helps control global warming. It does this by absorbing a lot of carbon dioxide, a gas that causes warming.

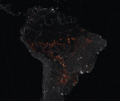

Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE) first reported the increase in fires in June and July 2019. They used satellites to watch the fires. By August 2019, the situation gained international attention. Smoke from the fires was so thick that it made the sky dark in São Paulo, a city thousands of kilometers away. This smoke was even visible from space.

By August 29, 2019, INPE reported over 80,000 fires across Brazil. This was a 77% increase from the year before. More than 40,000 of these fires were in the "Legal Amazon" area of Brazil, which holds 60% of the entire Amazon rainforest. Other countries like Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru also saw more fires. Over 906,000 hectares (about 2.2 million acres) of forest were lost to fires in 2019.

Besides affecting the global climate, the fires released a lot of harmful gases like carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. They also threatened the amazing variety of life (biodiversity) in the Amazon. Many indigenous people (native tribes) live in the forest, and their homes and way of life were also in danger. Experts estimated that the damage from these fires could cost Brazil billions of dollars over 30 years.

Many international leaders and environmental groups blamed Brazil's president, Jair Bolsonaro. They said his policies made it easier for people to cut down trees and start fires. At first, Bolsonaro didn't seem too worried. He said the criticism was overblown. But after more pressure, especially from the 45th G7 summit and a threat to a trade deal, he sent over 44,000 Brazilian soldiers to help fight the fires. He also signed a rule to stop such fires for 60 days.

Other Amazon countries were also affected. Bolivia, which is much smaller than Brazil, lost a similar amount of forest. Bolivia's president, Evo Morales, also faced criticism but took steps to fight the fires and ask for help. At the G7 summit, leaders agreed to give $22 million in emergency aid to the Amazonian countries.

Contents

- Understanding the Amazon Forest and Deforestation

- Different Kinds of Fires in the Amazon

- Fires in Brazil

- History of Deforestation and Fires in Brazil

- 2019 Brazil Dry Season Fires

- First Media Reports of the Fires

- Brazilian Government's Response

- Protests Against Brazilian Government Policies

- Impact on Native Peoples of Brazil

- International Responses to the Fires

- G7 Summit and Emergency Aid

- Amazon Country Summit

- Fires in Bolivia

- Fires in Paraguay's Pantanal

- Fires in Peru

- Environmental Impacts of the Fires

- International Actions to Help

- 2019 Wildfires in the Media

- Celebrity Responses to Amazon Wildfires

- Images for kids

- See also

Understanding the Amazon Forest and Deforestation

The Amazon rainforest is huge, covering about 670 million hectares (1.6 billion acres). For many years, people have worried about deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. This is because the Amazon plays a very important role in the world's climate.

Why the Amazon is Important for the Planet

The Amazon is like the world's biggest "carbon sink." This means it absorbs a lot of carbon dioxide from the air. It's estimated to take in up to 25% of the world's carbon dioxide. This gas is then stored in plants and other living things. Without the Amazon, there would be more carbon dioxide in the air. This would make global temperatures rise even faster.

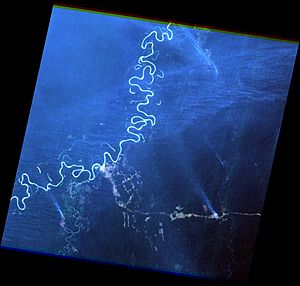

When the forest burns, it releases all that stored carbon dioxide back into the air. This makes global warming worse. The trees also release a lot of water vapor, which creates "flying rivers" that bring rain to other parts of South America. Scientists worry that the Amazon could reach a "tipping point." This means it could die out forever and turn into a dry grassland if climate change and human activities continue.

How Deforestation Happens in the Amazon

People cut down the Amazon forest to create land for farming, raising cattle, and mining. They also cut trees for wood. The most common way to clear land is using slash-and-burn. First, during the wet season (November to June), trees are knocked down with bulldozers. Then, during the dry season (July to October), the tree trunks are burned. Fires are most common in July and August.

Sometimes, people who do the burning are not careful. They might accidentally let the fires spread out of control. Even though most Amazon countries have laws against deforestation, these laws are often not enforced. This means a lot of slash-and-burn activity happens illegally.

Why Most Amazon Fires are Caused by Humans

Many fires are seen across the Amazon during the dry season. These are usually tracked by satellites. While natural wildfires can happen in the Amazon, they are very rare. Even with global warming, warm weather alone doesn't start fires in the Amazon. However, warm weather can make fires worse once they start. This is because it dries out plants, making them easier to burn.

An expert from INPE, Alberto Setzer, believes that 99% of Amazon wildfires are caused by humans. This happens either on purpose or by accident. Fires started by humans also tend to send smoke higher into the atmosphere. This is because they burn drier plants more intensely. Also, evidence shows that fires are often found near roads and existing farms, not in remote parts of the forest. This suggests human activity.

On November 18, 2019, Brazil announced that deforestation was the "worst in more than a decade." About 970,000 hectares (2.4 million acres) of forest were lost. In July 2020, satellite data showed that fires in the Amazon increased by 28% compared to July 2019. This means the destruction of the Amazon, which helps fight global warming, continued to be a big problem.

Different Kinds of Fires in the Amazon

Amazon fires can be grouped into three main types.

- Deforestation fires: These are fires used to prepare land for farming after trees have been cut down and left to dry.

- Agricultural burns: These fires are used to clear existing fields or by small farmers for their crops.

- Escaped fires: Sometimes, the fires from the first two types get out of control. They spread beyond the planned limits and burn into standing forests.

When a forest burns for the first time, the fire is usually not very strong. It mostly stays on the ground. But if a forest burns again and again, the fires become much stronger. Forest fires harm the Amazon's amazing variety of life. They also make it harder for trees to store carbon and help fight climate change. It's important to remember that the Amazon Basin has different dry seasons in different areas.

Fires in Brazil

Brazil holds 60% of the Amazon rainforest. This area is called Brazil's Legal Amazon (BLA).

History of Deforestation and Fires in Brazil

Brazil's role in cutting down the Amazon has been a big issue for decades. Since the 1970s, Brazil has lost about 12% of the forest. This is roughly 77.7 million hectares (192 million acres), an area larger than the US state of Texas. Most of this deforestation happened to get natural resources like wood and to clear land for farming and mining.

Raising cattle has been the main reason for deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon since the mid-1960s. The Amazon region has become the biggest cattle ranching area in the world. About 80% of deforested land is used for cattle. Seventy percent of land that was once forest, and 91% of land deforested since 1970, is now used for cattle pastures.

The demand for beef and soy exports, especially to China, has also driven deforestation. Brazil is one of the largest beef exporters. Ranchers often wait until the dry season to use slash-and-burn methods so their cattle can graze. Soybean production has also increased a lot. While slash-and-burn can be controlled, unskilled farmers might cause wildfires. Fires have increased as farming has moved further into the Amazon. Also, "land-grabbers" (people illegally taking land) have been cutting deep into protected forests and lands belonging to native tribes.

Past data from INPE shows that the number of fires in the BLA from January to August was often over 60,000 between 2002 and 2007. In 2003, it was as high as 90,000. Fire counts have usually been higher in years with droughts, especially during El Niño events.

Around the early 2000s, Brazil started taking more action to protect the Amazon. In 2004, the government created a plan to reduce deforestation. This plan aimed to control land use, monitor the environment, and promote sustainable activities. It also included penalties for breaking the rules. Brazil also bought more firefighting planes in 2012. By 2014, a US aid group was teaching native people how to fight fires. Because of these efforts, deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon dropped by 83.5% by 2012.

However, Brazil faced an economic crisis in 2014. To help its economy, the country focused heavily on exporting beef and soy. This caused deforestation rates to rise again. The Brazilian government also started cutting funding for scientific research.

To help with the deforestation plan, INPE developed systems to monitor the Amazon. One system, PRODES, uses detailed satellite images to track wildfires and deforestation each year. In 2015, INPE launched the Terra Brasilis project with five more systems. One of these, DETER, gives real-time alerts about wildfires every 15 days. This daily data is published online and later checked against the more accurate PRODES data.

By December 2017, INPE had updated its system to share fire data more easily. It launched a new software called TerraMA2Q, which helps monitor "irregular fires." INPE gets images daily from 10 foreign satellites, including NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites. These systems can count fires every day. However, they use images taken every two weeks to estimate how much forest area is lost.

When Jair Bolsonaro became President of Brazil in January 2019, his government changed policies. These changes weakened environmental protections. They made it easier for farmers to continue slash-and-burn practices, which sped up deforestation. People illegally taking land used Bolsonaro's election as a chance to cut into the lands of the Apurinã people, where some of the largest untouched rainforests are found.

Bolsonaro also cut $23 million from Brazil's environmental enforcement agency. This made it harder for the agency to stop deforestation. His government also divided the environmental agency, putting parts of it under the agriculture ministry, which is influenced by farming groups. They also weakened protections for natural reserves and native lands.

2019 Brazil Dry Season Fires

INPE warned the Brazilian government about a larger-than-normal increase in fires from June to August 2019. The first four months of the year were wetter than usual, which usually discourages slash-and-burn. But when the dry season started in May 2019, the number of wildfires jumped a lot. Also, temperatures from January to July 2019 were the second warmest on record. INPE reported an 88% increase in wildfires in June 2019 compared to the year before. Deforestation also increased in July 2019.

August 2019 saw a huge increase in wildfires. By August 11, the state of Amazonas declared a state of emergency. On August 16, Acre state also declared an environmental alert. In early August, farmers in Pará state even advertised a "Day of Fire" for August 10, 2019. They organized large slash-and-burn operations, knowing there was little chance of government interference. Soon after, the number of wildfires in that region increased.

On August 20, INPE reported 39,194 fires in the Amazon since January. This was a 77% increase from the same time in 2018. However, 2018 was a year with unusually few fires compared to historical data. INPE also reported that at least 74,155 fires were detected across all of Brazil. NASA later confirmed that the number of fires was higher than in previous years.

By August 29, 80,000 fires had broken out in Brazil. INPE also reported fires in other South American countries.

First Media Reports of the Fires

While INPE's data was available earlier, the wildfires didn't become a major news story until around August 20, 2019. On that day, smoke from fires in Rondônia and Amazonas made the sky dark in São Paulo around 2 p.m. São Paulo is almost 2,800 kilometers (1,700 miles) away from the Amazon basin. NASA and NOAA also published satellite images showing smoke plumes from the wildfires visible from space. These images and photos of the fires caught international attention. The fires became a trending topic on social media, with many world leaders, celebrities, and athletes expressing their concern.

Many news outlets called the Amazon wildfires in Brazil the most "alarming" compared to other fires happening around the world at the same time.

Brazilian Government's Response

Before August 2019, President Bolsonaro often made fun of environmental groups. He even joked about being "Captain Chainsaw." He claimed INPE's data was wrong and fired its director, Ricardo Galvão. Bolsonaro said Galvão was using the data to create an "anti-Brazil campaign." Bolsonaro also claimed that environmental groups had deliberately started the fires, but he didn't provide any proof. Environmental groups like WWF Brasil and Greenpeace denied his claims.

On August 22, Bolsonaro argued that Brazil didn't have enough resources to fight the fires. He said, "The Amazon is bigger than Europe, how will you fight criminal fires in such an area?"

Historically, Brazil has been protective of international involvement in the Amazon. Bolsonaro's government continued to speak out against any international oversight. He called French President Emmanuel Macron's comments "sensationalist" and accused him of interfering in a local problem.

However, with increasing international pressure, Bolsonaro seemed more willing to act. By August 23, 2019, he said his government would have "zero tolerance" for environmental crimes. On August 24, he sent the Brazilian military to help fight the wildfires. This included 43,000 troops and four firefighting aircraft, with $15.7 million allocated for operations. On August 28, Bolsonaro signed a rule banning fires in Brazil for 60 days. There were exceptions for fires used to maintain forest health, fight wildfires, and by native people. However, since most fires are set illegally, it was unclear how much impact this rule would have.

The president of Brazil's Chamber of Deputies, Rodrigo Maia, announced a committee to monitor the problem. He also said the Chamber would discuss solutions. After a report linked a WhatsApp group to the "Day of Fire," Bolsonaro ordered the Federal Police to investigate.

In November 2019, President Bolsonaro blamed actor and environmentalist Leonardo DiCaprio for the fires. He claimed that environmental groups set the fires to get donations. DiCaprio and other conservation groups strongly denied these accusations. Brazil banned clearing land by setting fire to it on August 29, 2019.

Other actions taken by the Brazilian government included accepting four planes from Chile to fight fires and $12 million in aid from the United Kingdom. Bolsonaro also softened his stance on aid from the G7 group of countries. He called for an international meeting with all countries that have parts of the Amazon rainforest to discuss its preservation.

Protests Against Brazilian Government Policies

Many people were concerned about the displacement of native people. Amnesty International pointed out that protections for native lands had changed. They urged other nations to pressure Brazil to restore these rights, as they are key to protecting the rainforest. Ivaneide Bandeira Cardoso, who helps native communities, said Bolsonaro was directly responsible for the increase in fires. She called the wildfires a "tragedy that affects all of humanity."

Thousands of Brazilians protested in major cities starting August 24, 2019. They challenged the government's response to the fires. Protesters around the world also held events at Brazilian embassies.

Impact on Native Peoples of Brazil

The slash-and-burn actions that caused the wildfires also threatened the approximately 306,000 native people in Brazil. These people live near or within the rainforest. Bolsonaro had spoken against respecting the land boundaries set for native people in Brazil's 1988 Constitution. Reports said that farmers, loggers, and miners, feeling supported by the government, were forcing native people off their lands, sometimes violently. Some native groups who traditionally use fire for farming are now being treated as criminals. Some tribes have promised to fight back against those destroying the forest to protect their lands.

International Responses to the Fires

Many international leaders and environmental groups criticized President Bolsonaro for the large number of wildfires in the Brazilian Amazon.

Several governments and environmental groups were worried about Bolsonaro's approach to the rainforest. French President Emmanuel Macron was very vocal. He called the Amazon wildfires an "international crisis." He also said the rainforest produces "20% of the world's oxygen," a statement that some experts disagreed with. He famously stated, "Our house is burning. Literally."

The fires also affected talks for a trade agreement between the European Union (EU) and Mercosur (a trade group including Brazil). Macron and Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar said they would not approve the trade deal unless Brazil committed to protecting the environment.

Finland's finance minister, Mika Lintilä, suggested the EU ban beef imports from Brazil until the country stops deforestation. The Rainforest Foundation Norway said that both the deforestation figures and the number of wildfires in 2019 were not normal. They warned that the Amazon could be reaching a "tipping point" where large parts of the forest might collapse.

On September 10, 2019, the US House Foreign Affairs Committee held a hearing called "Preserving the Amazon: A Shared Moral Imperative." An economist, Monica de Bolle, said the rainforest is like a "carbon bomb." She explained that the fires could release 200 million tons of carbon into the air each year. This would speed up climate change and change rainfall patterns.

G7 Summit and Emergency Aid

The wildfires became a major topic at the 45th G7 summit in France, led by President Macron. Macron wanted to discuss the fires and Bolsonaro's response. German Chancellor Angela Merkel also supported discussing the issue. Macron even suggested that an international law might be needed to protect the rainforest if a country's actions clearly harmed the planet. Bolsonaro was concerned that Brazil, not being part of the G7, would not be represented.

During the summit, Macron and Chilean president Sebastián Piñera helped arrange $22 million in emergency funding for Amazonian countries to fight the fires. However, Bolsonaro initially refused the funds for Brazil. He claimed Macron's interest was about protecting French farming businesses. Bolsonaro also criticized Macron by comparing the Amazon fires to the Notre-Dame de Paris fire, suggesting Macron should focus on his own country's problems. The governors of the Brazilian states most affected by the fires pressured Bolsonaro to accept the aid. Bolsonaro later said he would accept foreign aid, but only if Brazil decided how it was used.

Amazon Country Summit

On August 28, 2019, Brazil's Bolsonaro announced that countries sharing the Amazon rainforest (except Venezuela) would hold a summit in Colombia on September 6, 2019. Representatives from Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, and Suriname attended. They signed an agreement to work together to monitor the Amazon forest, respond to disasters, and share information. The agreement also aimed to reduce illegal deforestation in their countries.

Fires in Bolivia

Bolivia has 7.7% of the Amazon rainforest. In Bolivia, a traditional farming practice called chaqueo involves using controlled fires. This practice was first allowed in 2001.

By September 14, 2019, Bolivia, which is one-eighth the size of Brazil, had lost nearly 6 million acres (2.4 million hectares) of "forest and savanna." The fires destroyed about the same area of rainforest as in Brazil.

Fires in Santa Cruz Department

By August 16, Bolivia's Santa Cruz declared an emergency due to forest fires. From August 18 to August 23, about 800,000 hectares (2 million acres) of the Chiquitano dry forests were destroyed. This was more than what was typically lost over two years. By August 24, the fires had affected over 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of forestland in Santa Cruz. By August 26, wildfires had reached over 728,000 hectares (1.8 million acres) of Bolivia's grasslands and tropical forests.

On August 25, 4,000 government workers and volunteers were fighting the fires. By that date, 650,000 hectares (1.6 million acres) of tropical forest had burned in the Chiquitano regions. Like the Brazil fires, these fires happen during the dry season, but the number in 2019 was much higher than in previous years.

The Bolivian government stepped in when it became clear the fires were too big for local teams. President Morales sent soldiers and helicopters. On August 22, Morales hired the Boeing 747 Supertanker, the world's largest firefighting aircraft, to drop water over the Bolivian Amazon. Morales said many countries, including Spain, Chile, and France, offered help.

The government tried to find out what caused the fires. The Bolivian land management authority said 87% of the fires were in areas where burning was not allowed. Many environmental groups claimed that deforestation rates in Bolivia increased by 200% after the government allowed more land to be cleared for small farmers in 2015.

By September 9, the total forest area affected by fires in Bolivia was estimated at 1.7 million hectares (4.2 million acres). This was more than double the estimate from two weeks earlier. While some local officials asked Morales to declare a national disaster, the communication minister said a national emergency was enough to receive foreign help.

Fires in Paraguay's Pantanal

By August 22, Paraguay's government declared fire emergencies in the Alto Paraguay district and the UNESCO-protected Pantanal region. Paraguay's President Mario Abdo Benítez worked with Bolivia's Morales to coordinate efforts. By August 17, fires from Bolivia began to enter northern Paraguay's Three Giants natural reserve in the Pantanal. By August 24, Paraguay had lost 39,000 hectares (96,000 acres) in the Pantanal. A university representative regretted that this disaster didn't get as much media attention as the Amazon fires.

Most of the Pantanal, the "world's largest tropical wetland area," is in Brazil, but it also extends into Bolivia and Paraguay. An engineer monitoring satellite data said the Pantanal is a "complex, fragile, and high-risk ecosystem" because it's changing from a wetland to a farming area. The Pantanal is bordered by other important ecosystems. A national parks researcher said it's a shame that outsiders only know the Amazon, because the Pantanal is also a very important ecological place.

Fires in Peru

Peru saw nearly twice the growth in fires in 2019 compared to Brazil. Most of these fires were believed to be set illegally by ranchers, miners, and coca growers. Many fires were in the Madre de Dios region, which borders Brazil and Bolivia. However, these fires were not a direct result of those started in other countries. Local authorities were still concerned about the impact of smoke, especially carbon monoxide, on residents. In August 2019, 128 forest fires were reported in Peru.

Environmental Impacts of the Fires

Emissions from the Fires

By August 22, NASA published maps showing increased carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide from Brazil's wildfires. The European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service also reported a "noticeable spike" in these gases.

Areas downwind of the fires were covered in smoke. This smoke could last for months if the fires continued. Hospitals in cities like Porto Velho reported three times the usual number of patients affected by smoke in August 2019. Smoke can make breathing difficult and worsen conditions like asthma or bronchitis. It can also increase the risk of cancer, especially for young people and the elderly.

Impact on Biodiversity

- Further information: Extinction risk from global warming

The World Wildlife Fund stated that animals like the jaguar, which are already "near threatened," faced a more critical situation. This was due to the loss of food and habitat from the fires.

Scientists at the Natural History Museum explained that while some forests are used to fire, the Amazon rainforest is not. It is made up of lowland, wetland forests and is "not well-equipped to deal with fire." Other Amazon ecosystems, like the Cerrado region, are "fire-adapted" because their plants have thick, fire-resistant stems.

Mazeika Sullivan, a professor at Ohio State University, said the fires could greatly harm wildlife in the short term. Many Amazon animals are not used to such large fires. Animals like sloths, lizards, anteaters, and frogs might die in large numbers because they are small and can't move quickly. Unique species, like Milton's titi and Mura's saddleback tamarin, were also thought to be affected. Water animals could also be harmed if the fires changed the water's chemistry.

Long-term effects could be even worse. Parts of the Amazon rainforest's thick canopy (the top layer of trees) were destroyed. This exposed the lower parts of the ecosystem, changing how energy flows through the food chain. The fires also affect water chemistry (like reducing oxygen in the water), temperature, and erosion. This, in turn, affects fish and animals that depend on fish, like the giant otter.

International Actions to Help

On August 22, the Bishops Conference for Latin America called the fires a "tragedy." They urged the UN, the international community, and Amazonian governments to "take serious measures to save the world's lungs." Colombian President Ivan Duque wanted to lead a conservation agreement with other Amazon nations. He planned to present this to the UN General Assembly. Duque said, "We must understand the protection of our Mother Earth and our Amazon is a duty, a moral duty."

United Nations Secretary General António Guterres stated on August 23, "In the midst of the global climate crisis, we cannot afford more damage to a major source of oxygen and biodiversity."

2019 Wildfires in the Media

Media coverage mostly focused on the Amazon fires in Brazil. This meant the fires in Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay received less attention. The Amazon wildfires also happened shortly after major fires in Greenland and Siberia. This also drew attention away from those natural disasters.

Some photos shared on social media were actually from past fires in the Amazon or from fires elsewhere. News agencies published guides to help people check if photos were real or misleading.

Celebrity Responses to Amazon Wildfires

American actor Leonardo DiCaprio announced that his environmental organization, Earth Alliance, was donating $5 million. This money would go to local groups and native communities to help protect the Amazon. However, President Jair Bolsonaro later claimed DiCaprio's donations encouraged environmental groups to set fires. DiCaprio and other conservation groups strongly denied this.

Many celebrities used Instagram to speak out about the wildfires. For example, Cara Delevingne posted a picture of the fires with the caption "#PrayForAmazonia." Other celebrities who made public contributions included actresses Vanessa Hudgens and Lana Condor, and Japanese musician Yoshiki.

On August 26, 2019, Europe's richest man, Bernard Arnault, announced that his LVMH group would donate $11 million to help fight the Amazon rainforest wildfires.

American chef Eddie Huang said he became vegan because of the 2019 Amazon fires. Khloé Kardashian urged her Instagram followers to eat a plant-based diet for the same reason. Leonardo DiCaprio told his Instagram followers to "eliminate or reduce consumption of beef" because "cattle ranching is one of the primary drivers of deforestation."

The 2021 song "Amazonia" by the French metal band Gojira and its music video were created in response to the fires.

Images for kids

-

Amazon rainforest ecoregions as delineated by the WWF in white and the Amazon drainage basin in blue.

- 2019 California wildfires

- 2019 Siberia wildfires

- 2019 United Kingdom wildfires

- 2019 Washington wildfires

- 2019 wildfire season

- 2019 Southeast Asian haze

- 2019–20 Australian bushfire season

- 2020 Brazil rainforest wildfires

- Deforestation in Brazil

See also

In Spanish: Incendios de la selva amazónica de 2019 para niños

In Spanish: Incendios de la selva amazónica de 2019 para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |