Deforestation of the Amazon rainforest facts for kids

The Amazon rainforest is the world's largest rainforest. It covers a huge area of about 3 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles). This amazing forest holds more than half of all the tropical rainforests on Earth. It is also home to the most different kinds of plants and animals (this is called biodiversity).

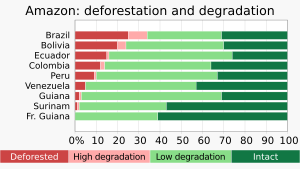

The Amazon region spreads across nine countries. Most of it (60%) is in Brazil. Smaller parts are in Peru (13%), Colombia (10%), Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia (6%), Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.

More than one-third of the Amazon rainforest is special land for Indigenous peoples. There are over 3,344 such areas. For a long time, Indigenous Amazonian people have used the forest for food, homes, water, materials, fuel, and medicines. The forest is also very important to their culture and beliefs. Even with outside pressures, deforestation is lower in these Indigenous areas. This is because giving legal land rights has helped reduce deforestation by 75% in Peru.

By 2022, about 26% of the forest was either cut down or badly damaged. The Council on Foreign Relations reported that 300,000 square miles of forest have been lost.

Cattle ranching in the Brazilian Amazon is the main reason for deforestation. It causes about 80% of all forest loss there. This makes it the biggest single cause of deforestation in the world. It adds to about 14% of the global deforestation each year. The government has even helped pay for some farming that leads to forest clearing. By 1995, 70% of the Amazon's former forest land was used for cattle. Also, 91% of the land cleared since 1970 was for cattle.

Other reasons for deforestation include small-scale subsistence agriculture (farming just enough for a family) and large farms growing crops like soy and palm. In 2011, soy farming caused about 15% of Amazon deforestation.

Satellite data from 2018 showed that deforestation in the Amazon was at its highest in a decade. About 7,900 square kilometers (3,100 sq mi) were destroyed between August 2017 and July 2018. The states of Mato Grosso and Pará had the most deforestation. Brazil's environment minister said Illegal logging was a cause. Others pointed to the growth of farming pushing into the rainforest. Experts warn that the forest might reach a point where it cannot make enough rain to survive. In the first nine months of 2023, deforestation dropped by 49.5%. This was thanks to the policies of Lula's government and international help.

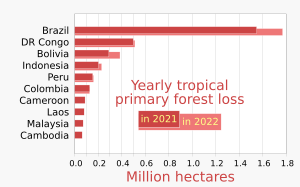

In May 2025, research from the University of Maryland showed that 2024 was the worst year ever for deforestation, including in the Amazon.

Contents

History of Amazon Deforestation

In ancient times, some parts of the Amazon rainforest had many people and farms. But when Europeans arrived in the 1500s, many people died from diseases and slavery. This caused the population to drop, and the forest grew back.

Until the 1970s, it was hard to get into the forest because there were few roads. Most of the forest was untouched, except for some areas along rivers. Deforestation grew quickly after highways were built deep into the forest. An example is the Trans-Amazonian Highway in 1972.

Farming became difficult in some Amazon areas because the soil was poor. A big change happened in the 1960s when settlers started farms in the forest. They used a method called slash-and-burn, where they cut and burn trees to clear land. But the soil quickly lost its goodness, and weeds took over.

In the Peruvian Amazon, areas like the Urarina's Chambira River Basin have poor soil. This means Indigenous farmers often have to clear new land. Raising cattle became popular in the Amazon because it needed less work and made good money. Also, the land was owned by the state. Some laws that allowed private ownership of land were criticized. People said these laws encouraged more deforestation and ignored the rights of Peru's Indigenous people, who often did not have legal papers for their land. One such law, Law 840, was stopped because it was against the constitution.

Illegal deforestation in the Amazon went up in 2015 after years of going down. This was mainly because people wanted products like palm oil. Brazilian farmers clear land to meet the demand for crops like palm oil and soy. Cutting down forests releases a lot of carbon into the air. If this continues, the world's remaining forests could disappear in 100 years. The Brazilian government started the RED program to fight deforestation. It helps African countries with education and money.

In January 2019, Brazil's president, Jair Bolsonaro, made a rule that gave the agriculture ministry control over some Amazon lands. Cattle ranchers and mining companies liked this decision. But critics said it put Indigenous people in danger and made Brazil contribute more to global climate change.

Reports from 2021 showed that deforestation increased by 22% from the year before. This was the highest level since 2006.

Why the Amazon Rainforest is Being Cut Down

Many things cause deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. These reasons come from local areas, countries, and even worldwide. People want the rainforest for cattle ranching, cutting down valuable hardwood trees, and land for homes and farms (especially for soybeans). Roads, including highways, are also built. Some people also collect medicinal plants. Deforestation in Brazil is also linked to a way of growing the economy that focuses on getting more land, rather than making things more efficient. It is important to know that Illegal logging is a common way trees are removed during deforestation.

Cattle Ranching

According to reports from 2004 and 2009, cattle ranching in the Brazilian Amazon causes about 80% of the deforestation. This is supported by the international trade of beef and leather. This makes it the biggest cause of deforestation in the world. It accounts for about 14% of all global deforestation each year. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reported in 2006 that 70% of the Amazon's former forest land is now used for cattle pastures. Also, 91% of the land cleared since 1970 is now for livestock.

The European Union–Mercosur Free Trade Agreement of 2019 created one of the world's largest free trade areas. But environmental groups and Indigenous rights advocates criticized it. They said it would lead to more Amazon deforestation by making it easier to sell Brazilian beef.

During Jair Bolsonaro's government, some environmental laws were made weaker. Money and staff for important government agencies were cut. Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest increased during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE) reported that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon went up by more than 50% in the first three months of 2020 compared to 2019.

In October 2024, Brazil's environmental agency, IBAMA, fined cattle ranches and meatpacking companies, including JBS SA (the world's largest meat packer), 365 million reais (about US$64 million). This was for being involved in illegal deforestation in the Amazon. The fines were for companies that raised or bought cattle from land cleared without permission.

Soy Bean Farming

Deforestation in the Amazon has happened because farmers clear land for large-scale farms. A study using NASA satellite data in 2006 showed that clearing land for these farms had become a big reason for deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. This change in land use has affected the region's climate. Researchers found that in 2004, a year with high deforestation, over 20% of the forests in Mato Grosso state were turned into farmland. In 2005, when soybean prices dropped by more than 25%, some areas of Mato Grosso saw less large-scale deforestation. This suggests that prices of other crops, beef, and timber can also affect how land is used in the future.

Growing soybeans, mainly for export and to make biodiesel and animal feed, has been a major cause of forest loss in the Amazon. As soybean prices went up, soy farmers expanded their farms into forest areas. However, a special agreement called the Soy Moratorium has greatly reduced deforestation linked to soy production. In 2006, big trading companies like Cargill promised not to buy soybeans grown in recently deforested areas of the Brazilian Amazon. Before this agreement, 30% of new soy farms were linked to deforestation, leading to very high deforestation rates. After eight years of the moratorium, a 2015 study found that even though the area for soy production grew by 1.3 million hectares, only about 1% of this new soy farming happened by cutting down forests. Because of the moratorium, farmers chose to plant crops on land that was already cleared.

The needs of soy farmers have been used to justify some controversial road projects in the Amazon. The Belém-Brasília highway (1958) and the Cuiabá-Porto Velho highway (1968) were the only paved federal highways in the Legal Amazon region that were open all year before the late 1990s. These two highways are seen as central to the "arc of deforestation," which is now the main area where forests are being cut down in the Brazilian Amazon. The Belém-Brasília highway attracted almost two million settlers in its first twenty years. The success of this highway in opening up the forest was repeated as more paved roads were built, leading to a huge wave of settlement. Many settlers came after these roads were finished, and they also had a big impact on the forest.

Logging

Logging means cutting down trees for money, mainly for the timber industry. This adds to the overall deforestation of an area. Deforestation is when forests and vegetation are permanently removed from an area. This often harms the environment, people, and the economy.

Logging usually involves these steps:

- Choosing trees: Loggers pick specific trees to cut based on their type, size, and how much they are worth. Valuable trees often cut include mahogany, teak, oak, and other hardwoods.

- Building access roads: Loggers build roads and paths in the forest to reach the chosen trees. These roads help move heavy machines, logging tools, and cut timber.

- Clearing plants: Before cutting trees, loggers often clear smaller plants and trees around the main trees. This makes it easier for machines to move.

- Cutting trees: The chosen trees are cut down using chainsaws or other machines. The cut trees are then prepared for more processing.

- Taking out timber: After trees are cut, loggers remove the timber from the forest. They cut off branches and cut the tree trunks into logs of the right size for transport.

- Moving logs: The logs are moved from the logging site to processing factories or storage areas. Trucks, boats, or helicopters are used, depending on how easy it is to reach the area.

- Processing and using: At the factories, the logs are turned into lumber, plywood, or other wood products. These products are used in building, making furniture, or for paper.

Logging has big and wide-ranging effects on deforestation. These effects include losing biodiversity in the affected areas. Logging often destroys forest ecosystems, meaning many plant and animal species lose their habitat. Losing biodiversity also makes forests less able to handle global changes.

Trees help fight climate change by taking in carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. When trees are cut, the stored carbon is released back into the air as carbon dioxide. This adds to greenhouse gases and climate change. A 2023 study found that carbon stored in the Amazon was reduced after logging. This shows how logging harms the forest's ability to store carbon and control global carbon emissions.

Logging also causes soil erosion and damage. Forests protect the soil from being washed away by wind and water. When trees are removed, the exposed soil is more likely to erode. This leads to losing fertile topsoil and damaging the land. Also, more open areas in the forest due to logging have led to more herbivores eating seedlings in the Amazon. This means seedlings are damaged or eaten more often, harming the soil and ecosystem.

Forests are very important for the water cycle. They act like natural sponges, controlling water flow and keeping water clean. They have big effects on local ecosystems, climate, and farming. Logging and deforestation disrupt these important jobs. They can also lead to less rainfall and a higher risk of drought.

Many Indigenous peoples and communities rely on forests for their lives, cultural practices, and food. Deforestation and logging can force these communities to move. It can also harm their traditional way of life and cause social problems. Conflicts over land and logging rights have led to the deaths of many Indigenous people. Indigenous territories in the Amazon also help protect against deforestation, logging, and wildfires. So, logging in these areas is bad for the whole region.

While logging can create jobs and make money, unsustainable logging (cutting too many trees too fast) can use up forest resources. This harms long-term economic benefits.

Efforts to deal with the effects of logging include using sustainable forest management (managing forests in a way that they can last), planting new trees, creating protected areas, enforcing rules, and helping local communities find other ways to make a living.

A 2013 paper found that logging in the Amazon rainforest was linked to less rain in the area. This led to lower crop yields. This suggests that, overall, Brazil does not gain money by logging, selling trees, and using the cleared land for cattle.

Oil and Gas Development

Oil and gas projects in the western Amazon are a big reason for deforestation and related environmental problems. These projects cause forest loss, water pollution, and force Indigenous peoples to move. There are not enough strong rules, which makes these areas more likely to be exploited. This creates many threats to the Amazon's biodiversity and local communities. A September 2016 report said that the US importing crude oil is linked to about 50,000 square kilometers (20,000 sq mi) of rainforest destruction in the Amazon. It also causes a lot of greenhouse gas emissions. These effects are mostly in the western Amazon countries of Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia. The report also said that oil exploration is happening in another 250,000 square kilometers (100,000 sq mi) of rainforest.

Roads

About 95% of deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest happens within 3.4 miles of a road. Forest clearing always starts near new roads, then spreads further. In December 2023, the lower house of the Brazilian Congress approved a bill to pave the highway BR-319 (Brazil highway). This could threaten the rainforest. The bill says the road is "critical infrastructure, essential to national security, requiring its trafficability to be guaranteed."

Mining

Mining is a big reason for deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. Between 2005 and 2015, it caused 9% of deforestation. More mining activities in the region have led to higher deforestation. This has many environmental effects, including droughts, wildfires, floods, and general damage to the local climate.

Climate Change

Climate change greatly increases the chance of droughts in the Amazon rainforest. These droughts severely harm the forest. In 2023, the Brazilian Amazon had widespread droughts that damaged the river system. River levels dropped to record lows. World Weather Attribution found that climate change and higher global temperatures are the main reasons for the region's lack of rain and droughts.

Other Causes

In August 2019, a long forest fire happened in the Amazon. It greatly added to deforestation that summer. About 1,340 square kilometers (519 sq mi) of the Amazon forest were lost. It is also worth noting that some deforestation in the Amazon has been caused by farmers clearing land for small-scale subsistence agriculture (farming just enough for their families).

How Much Forest is Being Lost

In the early 2000s, deforestation in the Amazon rainforest was increasing. In 2004, about 27,423 square kilometers (10,588 sq mi) of forest were lost each year. After that, the rate of forest loss generally slowed between 2004 and 2012. However, there were increases in deforestation in 2008, 2013, and 2015.

Recent information shows that the loss of forest cover is speeding up again. Between August 2017 and July 2018, about 7,900 square kilometers (3,100 sq mi) of forest were cut down in Brazil. This was a 13.7% increase from the year before and the largest area cleared since 2008. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest greatly increased in June 2019, rising more than 88% compared to the same month in 2018. It more than doubled in January 2020 compared to January 2019.

In August 2019, many forest fires were reported, totaling 30,901 individual fires. This was three times more than the year before. However, the number of fires dropped by one-third in September. By October 7, it had fallen to about 10,000. It is important to know that deforestation is considered to have worse effects than burning. Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE) estimated that at least 7,747 square kilometers (2,991 sq mi) of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest were cleared in the first half of 2019. INPE later reported that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon reached a 12-year high between August 2019 and July 2020.

Brazil's deforestation numbers are given yearly by the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE). They use satellite images taken during the dry season in the Amazon by the Landsat satellite. These estimates might only focus on the loss of the Amazon rainforest. They might not include the loss of natural fields or savannah within the Amazon biome.

Estimated Loss by Year

| Period | Estimated remaining forest cover in the Brazilian Amazon (km2) |

Annual forest loss (km2) |

Percent of 1970 cover remaining |

Total forest loss (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre–1970 | 4,100,001 | — | — | — |

| 1977 | 3,955,870 | 21,130 | 96.5% | 144,130 |

| 1978–1987 | 3,744,570 | 211,300 | 91.3% | 355,430 |

| 1988 | 3,723,520 | 21,050 | 90.8% | 376,480 |

| 1989 | 3,705,750 | 17,770 | 90.4% | 394,250 |

| 1990 | 3,692,020 | 13,730 | 90.0% | 407,980 |

| 1991 | 3,680,990 | 11,030 | 89.8% | 419,010 |

| 1992 | 3,667,204 | 13,786 | 89.4% | 432,796 |

| 1993 | 3,652,308 | 14,896 | 89.1% | 447,692 |

| 1994 | 3,637,412 | 14,896 | 88.7% | 462,588 |

| 1995 | 3,608,353 | 29,059 | 88.0% | 491,647 |

| 1996 | 3,590,192 | 18,161 | 87.6% | 509,808 |

| 1997 | 3,576,965 | 13,227 | 87.2% | 523,035 |

| 1998 | 3,559,582 | 17,383 | 86.8% | 540,418 |

| 1999 | 3,542,323 | 17,259 | 86.4% | 557,677 |

| 2000 | 3,524,097 | 18,226 | 86.0% | 575,903 |

| 2001 | 3,505,932 | 18,165 | 85.5% | 594,068 |

| 2002 | 3,484,281 | 21,651 | 85.0% | 615,719 |

| 2003 | 3,458,885 | 25,396 | 84.4% | 641,115 |

| 2004 | 3,431,113 | 27,772 | 83.7% | 668,887 |

| 2005 | 3,412,099 | 19,014 | 83.2% | 687,901 |

| 2006 | 3,397,814 | 14,285 | 82.9% | 702,186 |

| 2007 | 3,386,163 | 11,651 | 82.6% | 713,837 |

| 2008 | 3,373,252 | 12,911 | 82.3% | 726,748 |

| 2009 | 3,365,788 | 7,464 | 82.1% | 734,212 |

| 2010 | 3,358,788 | 7,000 | 81.9% | 741,212 |

| 2011 | 3,352,370 | 6,418 | 81.8% | 747,630 |

| 2012 | 3,347,799 | 4,571 | 81.7% | 752,201 |

| 2013 | 3,341,908 | 5,891 | 81.5% | 758,092 |

| 2014 | 3,336,896 | 5,012 | 81.4% | 763,104 |

| 2015 | 3,330,689 | 6,207 | 81.2% | 769,311 |

| 2016 | 3,322,796 | 7,893 | 81.0% | 777,204 |

| 2017 | 3,315,849 | 6,947 | 80.9% | 784,151 |

| 2018 | 3,308,313 | 7,536 | 80.7% | 791,687 |

| 2019 | 3,298,551 | 9,762 | 80.5% | 801,449 |

| 2020 | 3,290,125† | 8,426 | 80.2% | 809,875 |

| 2021 | 3,279,649 | 10,476 | 80.0% | 820,351 |

| 2022 | 3,268,049 | 11,600 | 79.7% | 831,951 |

| 2023 | 3,260,097 | 7,952 | 79.5% | 839,903 |

| 2024 | 3,253,809 | 6,288 | 79.4% | 846,191 |

| 2025 | 3,248,545 | 5,264 | 79.2% | 851,455 |

†Value calculated from estimated forest loss, not directly known.

Effects of Deforestation

Cutting down the Amazon rainforest and losing its biodiversity (many different kinds of life) creates a big risk of changes that cannot be undone. Studies suggest that deforestation might be nearing a "tipping point." This is a point where large parts of the forest could turn into a dry grassland (savanna) or even a desert. This would have terrible effects on the global climate. This tipping point could cause a collapse of biodiversity and ecosystems (natural communities) in the region that would keep getting worse. If this tipping point is not stopped, it could severely impact the economy, natural resources, and ecosystem services (benefits from nature). A study in 2022 showed that more than three-quarters of the Amazon rainforest has become less able to recover since the early 2000s. This puts it at risk of dying back, which would harm biodiversity, carbon storage, and climate change.

To keep a lot of different kinds of life, research suggests that at least 40% of the Amazon forest should remain.

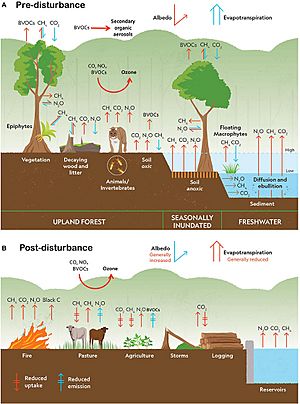

Effect on Global Warming

Deforestation, along with other ways ecosystems are destroyed (like peatbog degradation), can have many effects. It can reduce how much carbon the land can absorb. It also adds to more emissions through things like wildfires, changes in how land is used, and less healthy ecosystems. These impacts can mess up the normal ways ecosystems absorb carbon, leading to stress and imbalance.

Historically, the Amazon Basin has been very important for absorbing carbon. It used to take in about 25% of the carbon absorbed by land worldwide.

However, a scientific review from 2021 shows that the Amazon basin is now releasing more greenhouse gases than it absorbs overall. This change is due to climate change and human activities in the region. Especially wildfires, current land-use practices, and deforestation. These factors release substances that are likely to cause a net warming effect. Warmer temperatures and changing weather patterns also affect the forest's biology, further stopping it from absorbing CO2.

According to research by Elena Shevliakova and Stephen Pacala, completely cutting down the Amazon would cause a global temperature rise of 0.25 degrees. In 2023, even with deforestation, the forest still held more than 150 billion metric tons of carbon.

Effect on Water Supply

Cutting down the Amazon rainforest has greatly affected Brazil's freshwater supply. This especially impacts the agricultural industry, which has been involved in clearing the forests. In 2005, some parts of the Amazon basin had the worst drought in over a century. This is due to two main reasons:

- The rainforest is very important for creating rainfall across Brazil, even in far-off areas. Deforestation made the effects of droughts in 2005, 2010, and 2015–2016 worse.

- The rainforest helps create rainfall and store water. This water then supplies freshwater to the rivers that provide water to Brazil and other countries.

Effect on Local Temperature

In 2019, scientists did research showing that if deforestation continues as usual, the Amazon rainforest's destruction will lead to a temperature increase of 1.45 degrees in Brazil. They said this temperature rise could have many bad effects. These include more human deaths, higher electricity demand, less agricultural yield (crop production), and fewer water resources. It could also lead to the collapse of biodiversity, especially in tropical areas. Also, local warming might cause species to move to new places, including those that spread infectious diseases. The researchers believe that deforestation is already causing the temperature rise seen today.

Other research suggests that if the Amazon is completely deforested, the region itself (including 7 million square kilometers, 9 states in Brazil, and 8 other countries) would become almost impossible to live in. The temperature would rise by more than 4.5 degrees, and rainfall would be cut by a quarter.

Effect on Indigenous People

More than one-third of the Amazon forest is set aside as Indigenous territory. There are over 4,466 officially recognized territories. Until 2015, about 8% of deforestation in the Amazon happened within forests where Indigenous peoples lived. In contrast, 88% happened in areas outside Indigenous territories and protected areas. This is true even though these areas make up less than 50% of the total Amazon region. Indigenous communities have always relied on the forest for food, shelter, water, materials, fuel, and medicines. The forest is very important to their culture and beliefs. Because of this, deforestation rates are usually lower within Indigenous Territories, even though there are still pressures to clear land for other uses.

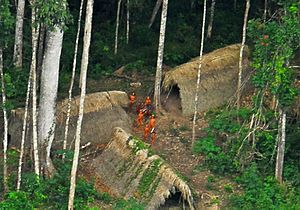

During the deforestation of the Amazon, native tribes have often been treated badly. Loggers entering Indigenous lands have led to fights that resulted in deaths. Some uncontacted Indigenous groups have come out of the forests and met mainstream society because of threats from outsiders. When uncontacted tribes meet outsiders, they are at risk of diseases they have little protection against. This can cause entire tribes to be severely affected by sickness, leading to many deaths in just a few years.

There has been a long struggle over who controls Indigenous territories in the Amazon, mainly involving the Brazilian government. The demand for these lands has come partly from the goal of making Brazil's economy stronger. Many people, including ranchers and land speculators from the southeast, have tried to claim these lands for their own money gain. In early 2019, Brazil's newly elected president, Jair Bolsonaro, issued an order giving the agriculture ministry power to control the land used by Indigenous tribes in the Amazon.

In the past, mining was allowed in the territory of an isolated Indigenous group called the Yanomami. The conditions these Indigenous peoples faced led to many health problems, including tuberculosis. If their lands are used for more development, many tribal communities will be forced to move. This could lead to loss of life. Besides the mistreatment of Indigenous peoples, using up the forest itself will mean losing important resources they need for their daily lives.

Research in the Peruvian Amazon shows that giving legal land titles to Indigenous lands greatly reduces deforestation rates. Land titling efforts led to a 75% reduction in deforestation over two years. Such policies give Indigenous communities the legal power to protect their land from outsiders and exploitation. This is a strong tool for fighting deforestation in the Amazon.

Between 2013 and 2021, deforestation within Indigenous territories in the Brazilian Amazon increased by 129%. This was mainly caused by illegal mining. These activities threaten biodiversity and harm the culture and environment of these lands. Because environmental policies and protections in Brazil were weakened in the second half of the 2010s, the deforestation rate in Indigenous territories was 195% higher between 2019 and 2021 than in the previous six years. Also, 59% of the carbon emissions measured within Indigenous territories between 2013 and 2021 happened in the last three years of the study.

The Yanomami people in Brazil have faced serious problems because of illegal gold mining in their lands. Mining activities have caused deforestation, water pollution, and a rise in malaria cases among the Yanomami. President Lula's government has taken steps to fix these issues, including efforts to take back and protect Yanomami lands. In 2012, the Yanomami organization HORONAMI said they were worried: “Illegal miners keep destroying our lands, and the government must act fast to stop these abuses and investigate the harm being done in the Upper Ocamo region.” In 2020, a report quoted Yanomami leaders saying they were frustrated with Brazilian authorities: “We feel completely abandoned; the government ignores the illegal activities that poison our rivers and bring disease to our people.”

Dario Kopenawa, vice president of the Hutukara Yanomami Association, has stressed how important government help is. He said, “The Brazilian government must do its job of protecting, where every Brazilian citizen, not just the Yanomami, feels protected. It is not a favor, but a duty from the constitution. It is necessary to stop mining projects on Indigenous lands because they are illegal under Brazilian law.”

Recent government raids against illegal gold mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory have shown how much deforestation these activities have caused. Using computer programs and satellite images, researchers estimate that over 2,000 hectares of forest have been cut down due to gold mining since 2019. About 67% of this deforestation (around 1,350 hectares) happened in 2022 alone. The deforestation is widespread, affecting areas along the Uraricoera, Parima, and Mucajai Rivers.

Efforts to Stop and Reverse Deforestation

Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg announced on September 16, 2008, that the Norwegian government would give US$1 billion to the new Amazon Fund. This money would be used for projects to reduce deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

In September 2015, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff spoke at the United Nations. She reported that Brazil had successfully reduced the deforestation rate in the Amazon by 82%. She also shared Brazil's goals for the next 15 years. These included stopping all illegal deforestation, restoring and replanting 120,000 square kilometers (46,000 sq mi) of forest, and fixing 150,000 square kilometers (58,000 sq mi) of damaged pastures.

In August 2017, Brazilian President Michel Temer removed the protected status of an Amazon nature reserve. This area was as big as Denmark and was in the northern states of Pará and Amapá.

In April 2019, a court in Ecuador ordered a stop to oil exploration in an area of 1,800 square kilometers (690 sq mi) within the Amazon rainforest.

In May 2019, eight former environment ministers in Brazil expressed worries about increasing deforestation in the Amazon during Jair Bolsonaro's first year as president. Carlos Nobre, an expert on the Amazon and climate change, warned in September 2019 that if deforestation continued at its pace, the Amazon forest could reach a tipping point within 20 to 30 years. This could cause large parts of the forest to turn into a dry savanna, especially in the southern and northern regions.

Bolsonaro rejected attempts by European politicians to get involved in Amazon rainforest deforestation. He said it was Brazil's internal business. He supported opening more areas, including in the Amazon, for mining. He also mentioned talking with US President Donald Trump about a joint plan for the Brazilian Amazon region.

Brazilian Economy Minister Paulo Guedes believed that other countries should pay Brazil for the oxygen produced within its borders but used elsewhere.

In late August 2019, after international concern and warnings from experts about the growing fires, the Brazilian government, led by Jair Bolsonaro, took steps to fight the fires. These steps included a 60-day ban on clearing forests using fires. They also sent 44,000 soldiers to fight the fires, received four planes from Chile for firefighting, accepted a $12 million aid package from the UK government, and softened his stance on aid from the G7. Bolsonaro also called for a meeting of Latin American countries to discuss preserving the Amazon.

On November 2, 2021, during the COP26 climate summit, over 100 countries, representing about 85% of the world's forests, made an important agreement to end deforestation by 2030. This agreement was an improvement on the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests. That earlier agreement aimed to reduce deforestation by 50% by 2020 and end it by 2030. Brazil is now a part of this new agreement. It is worth noting that deforestation increased between 2014 and 2020 despite the previous agreement.

In August 2023, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva hosted a meeting in Belem with eight South American countries. The goal was to work together on policies for the Amazon basin and create a plan to save the world's largest rainforest. This meeting also prepared for the COP30 UN climate talks in 2025.

In the first 8 months of 2023, the deforestation rate in the Brazilian Amazon dropped by 48%. This prevented 196 million tons of CO2 from being released into the atmosphere. Money from the Amazon Fund and cooperation among Amazonian nations played a big part in this. In the first 9 months of 2023, deforestation dropped by 49.5%, even with the worst drought in 40 years. Wildfires in September 2023 decreased by 36% compared to September 2022. Switzerland and the United States gave 8.4 million dollars to the Amazon fund to help prevent deforestation.

According to Amazon Conservation's MAAP forest monitoring program, the deforestation rate in the Amazon rainforest as a whole, from January 1 to November 8, 2023, dropped by 55.8% compared to the same period in 2022. This trend gives hope for the Amazon. The reduction in deforestation in Brazil (59%), which is the main reason for this trend, is likely due to Lula's environmental policies. In Colombia, the deforestation rate fell by 66.5%. This is probably due to the policies of Gustavo Petro and a change in the actions of former guerrilla fighters who control part of the forest. It is still not clear what caused the decline in Bolivia (60%) and Peru (37%). Bolivia has a relatively high rate of forest loss due to wildfires, but those are not happening in the Amazon.

In September 2024, Sawré Muybu, an Indigenous land belonging to the Munduruku people, received official recognition. This is seen as an important step in fighting deforestation. However, 44 more territories are still waiting for recognition.

Cost of Rainforest Conservation

According to the Woods Hole Research Institute (WHRC) in 2008, stopping deforestation in the Brazilian rainforest would need an annual investment of US$100–600 million. A more recent study in 2022 suggested that saving about 80% of the Brazilian rainforest is still possible. It would cost an estimated US$1.7–2.8 billion each year to protect an area of 3.5 million square kilometers. By preventing deforestation, it would be possible to avoid carbon emissions at a cost of US$1.33 per ton of CO2. This is much lower than the cost of reducing emissions through renewable fuel subsidies (US$100 per ton) or programs like building insulation (US$350/ton).

Future of the Amazon Rainforest

Based on the deforestation rates seen in 2005, predictions showed that the Amazon rainforest would shrink by 40% within two decades. While the rate of deforestation has slowed since the early 2000s, the forest continues to get smaller each year. Satellite data analysis shows a big increase in deforestation since 2018.

See also

In Spanish: Deforestación en el Amazonas para niños

In Spanish: Deforestación en el Amazonas para niños

- 2019 Brazil wildfires

- Belo Monte Dam

- Cattle ranching

- Clearcutting

- Construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway

- Deforestation

- Deforestation in Brazil

- Flying river

- Livestock's Long Shadow

- Logging

- IBAMA

- INCRA

- Mennonites#Environmental impacts - Mennonite colonization has been identified as a driver of deforestation

- Population and energy consumption in Brazilian Amazonia

- Risks of using unsustainable agricultural practices in rainforests

- Selective logging in the Amazon rainforest

- Terra preta

- Non-timber forest products

- Orinoco Mining Arc

Fauna

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |