Alice Milligan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alice Milligan

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 4 September 1865 Gortmore, County Tyrone, Ireland

|

| Died | 13 April 1953 Trichur, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

|

| Nationality | Irish |

| Education | Methodist College Belfast |

| Occupation | Writer, Poet, Dramatist |

| Movement | Gaelic League, Irish Women's Association, Sinn Féin |

Alice Letitia Milligan (born September 4, 1865 – died April 13, 1953) was an important Irish writer and activist. She used the pen name Iris Olkyrn. Alice was a key figure in the Celtic Revival in Ireland, which was a time when people wanted to celebrate Irish culture and history. She also strongly supported women's involvement in politics and culture. Even though she grew up in a Protestant family that supported staying with Britain, she became a strong supporter of Irish independence.

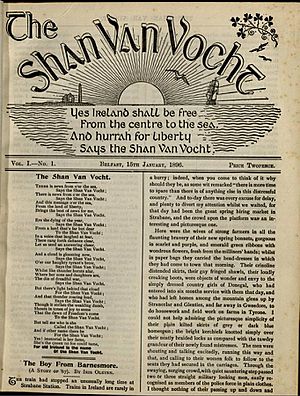

Alice was very famous around the year 1900. In Belfast, she helped create a political and literary magazine called The Shan Van Vocht (1896–1899) with her friend Anna Johnston. In Dublin, her play "The Last Feast of the Fianna" was performed by the Irish Literary Theatre. This play showed her unique way of telling old Celtic legends as Irish national stories.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Family and School Days

Alice Milligan was one of nine children. Her mother, Charlotte Burns, worked in a linen shop. Her father, Seaton Milligan, sold drapery. They lived in a village near Omagh, County Tyrone. In 1879, her father's job moved the family to Belfast. There, Alice went to Methodist College, Belfast. This school was one of the first to teach both boys and girls together. Her first poems were printed in the school magazine.

Alice's father was a liberal unionist, meaning he supported Ireland staying part of the UK but also believed in fair treatment for all. He was also a well-known expert in old things (an antiquarian). He held talks and lectures for local workers. He often discussed history, world events, and books with Alice. Alice also said she was influenced by a family servant named Jane. Jane shared stories about her previous employer, Mary Ann McCracken. Mary Ann was the sister of Henry Joy McCracken, a leader of the Society of United Irishmen. He was executed after the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Mary Ann spent her life helping women and the poor in Belfast.

Alice and her father were both part of the Belfast Naturalists' Field Club. They wrote a travel book about Ireland called Glimpses of Erin (1888). In this book, her father wrote that "patriotism" (love for one's country) is a good thing. He believed that by living in our own land and doing our best for it, we can follow the rule "Do unto others as you would that they should do to you."

Learning Irish

After studying English history and literature in London for a year, Alice trained to be a teacher. In 1888, she got a job teaching Latin in Derry. Here, she became interested in the Irish language. As a child, she had only heard farm workers speak it. In 1891, she moved to Dublin for another job. She wanted to learn Irish but couldn't find a school or group until the Gaelic League was formed in 1893. So, she took private lessons and read Irish books and history at the National Library of Ireland.

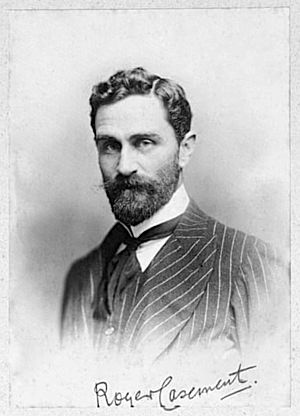

Alice was never completely fluent in Irish. Because of this, Patrick Pearse didn't like it when the Gaelic League hired her as a traveling lecturer in 1904. But Alice proved herself. She used costumed tableaux vivants (living pictures) to show Irish history or stories. She learned this skill when helping with the Irish exhibit at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. With these, she set up new branches of the Gaelic League all over Ireland and raised money. In Ulster, she focused on getting Protestants to join, working with people like Douglas Hyde and Roger Casement.

Becoming a Political Voice

A Royal Democrat

In Dublin, Alice saw the start of the Irish cultural revival. She also saw the end of Charles Stewart Parnell's political career. Parnell was a leader of Irish nationalism. In June 1891, she saw him at a public meeting. He looked "beaten and ashamed" because of a scandal involving his affair with Kitty O'Shea. In her poem "At Maynooth", she compared this to how George V was welcomed at a Catholic seminary in 1911.

Alice was very interested in Parnell and his idea of nationalism that didn't favor any religion. She followed his speeches and sketched him. She said this changed her political views. Before, she thought of herself as a "Tory and Protestant" because of her upbringing. She felt her formal education had made her blind to her own country's literature and history. In May 1891, she wrote in her diary: "While in the tram going up O’Connell Street I turned into a Parnellite."

Alice's first novel, A Royal Democrat, was published in 1891 under her pen name "Iris Olkyrn." It was a story about a future Prince of Wales who, born to an Irish mother, helps his people fight for land rights and an Irish Parliament. The book didn't do well with nationalist newspapers.

Remembering 1798

In 1893, Alice returned to Belfast. She lived with Anna Johnston, whose father was a leader in the Irish Republican Brotherhood. With their neighbor, Mary Ann Bulmer, they started the Irish Women's Association (IWA) in Belfast. Their goal was to share "national ideas among the women" and keep up the city's national and literary reputation. Alice also wrote a column called "Notes from the North" for the Irish Weekly Independent. She wanted to remind people in Dublin about the contributions of women and the North to the Irish cause.

Alice, Anna, and Mary Ann became friends with Francis Joseph Bigger. He was a rich Presbyterian lawyer and an expert in old things, like Alice's father. Bigger was known for hosting famous writers and artists at his home, Ard Righ. Alice met James Connolly, Roger Casement, and W.B. Yeats there. She walked with Yeats on Cave Hill, which she considered "holy" because Wolfe Tone and McCracken had pledged for Irish independence there. But Yeats disappointed her because he wasn't interested in the 1798 rebellion.

Alice and Bigger both loved the 1798 rebellion. They tried to organize a celebration in Belfast for its 100th anniversary. Alice wrote a book called Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone (1898). However, the descendants of the Protestants who fought in 1798 limited the celebrations to Catholic areas. A trip to the grave of Betsy Gray, a hero of the Battle of Ballynahinch, ended in a fight. Unionists destroyed her memorial stone. Alice's focus on Belfast's republican past showed how much the city had changed.

Alice also felt that women were being left out of the Centenary meetings. These meetings were being used by politicians to get Catholic votes. So, she started the Women's Centenary Union through the IWA. In April 1897, she asked readers of The Shan Van Vocht: "Is it too much to ask [...] that the women of Ireland, who are not asked to have any opinion whatever as to who shall have the right to speak for Ireland in the British Parliament, should form the Union which an historic occasion demands".

The Shan Van Vocht Magazine

The Two-Penny Journal

Alice Milligan and Anna Johnston created The Shan Van Vocht (which means "The Poor Old Woman" in Irish). They worked in Robert Johnston's timber yard. They had previously edited another paper, but they were fired because they supported freedom for Fenian prisoners.

Their new two-penny monthly magazine quickly became popular. Alice and Anna promoted it as they traveled for the Irish Women's Association. They found people to sell the magazine in Dublin, Derry, Glasgow, and New York. Within a year, people from Irish communities in South Africa, Canada, Argentina, and Australia were subscribing. Maud Gonne, another famous Irish activist, admired the "daring little paper."

The magazine was similar to The Nation, a paper from the 1840s. The Shan Van Vocht offered a mix of poems, stories, Irish history, political analysis, and announcements.

Bringing People Together

The very first issue in January 1896 featured an article by James Connolly called "Socialism and Nationalism." He argued that Irish nationalism needed to challenge the power of rich capitalists and landlords. Alice published more of Connolly's writings and letters from readers who liked his ideas. However, while Alice agreed with Connolly's views on workers' rights, she didn't support his Irish Socialist Republican Party.

Alice's own writings in the magazine focused on bringing people together, no matter their religion or social class. This was like the idea of the United Irishmen. Her stories often showed people from different backgrounds falling in love across divides. For example, one story was about a young Protestant woman in Belfast who secretly loved a Catholic rebel. She showed her support for him by wearing green slippers and black (mourning) crepe at a British ball.

The writer Seumas MacManus said that The Shan Van Vocht "revived Irish nationalism when it was perishing." Padraic Colum, another writer, said the magazine had a "freshness that came from its femininity." Many women contributed to it. He also noted its nationalism was from the North and not focused on Parliament.

Despite its popularity, the magazine struggled to get enough money to keep going. In April 1899, after forty issues, Mark F. Ryan of the IRB convinced Alice and Anna to pass the project on. The magazine's subscriber list went to Arthur Griffith for his new weekly paper, the United Irishman, which was the start of Sinn Féin.

Irish Republican Views

Alice Milligan had "romantic visions of marching soldiers and green flags flying." She did not support violent acts like the Fenian dynamite campaign of the 1880s.

However, she saw the 1916 Easter Rising differently. This rebellion in Dublin, and the deaths of people she knew like Connolly and Tomas MacDonagh, deeply affected her. She visited Casement in prison in London. They had been together in Larne in 1914 when unionists brought German guns into the port. Casement told her that Irish nationalists would need to do the same. On August 3, 1916, she was outside Pentonville Prison and heard the cheers that meant Casement had been executed. Back in Dublin, she wrote plays and poems to help raise money for Irish political prisoners.

Alice supported Sinn Féin in the 1918 election. She campaigned for Winifred Carney in Belfast. She was very upset by the Irish Civil War that followed. But she sided with Éamon de Valera in rejecting the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. She refused to accept Ireland being a dominion (like Canada or Australia) and the division of Ireland instead of a full republic.

A Playwright

Cultural Work

While her parents accepted her views, Alice's childhood community often left her out. In nationalist groups, her Protestant background sometimes worked against her. But her important role in the cultural revival won many people over.

In 1914, Tomas MacDonagh called Alice "the most Irish of living poets and therefore the best." He compared her to Thomas Davis, another famous Irish writer. W.B. Yeats was not as impressed. He told her to focus on plays rather than poetry, partly because of the comparison to Davis's patriotic poems.

“The Last Feast of the Fianna”

From 1898, Alice quickly wrote eleven plays. These were performed by groups like Maud Gonne's Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland), the Gaelic League, and the Irish Literary Theatre. In February 1901, the Irish Literary Theatre performed “The Last Feast of the Fianna” in Dublin. This play showed a part of the Oisin legend. It was a play that brought to life the old, pre-Christian Ireland.

The play didn't have much action. It used music (written by her sister Charlotte) to create "picturesque stillness" on stage. This was similar to the "living pictures" Alice used for the Gaelic League. One reviewer said that Alice's method was "the proper road" for creating a national drama. Yeats admitted the play "touched the heart." But Augusta, Lady Gregory, who helped Yeats start the Irish Literary Theatre, didn't like it. She found the long speeches "intolerable."

Her Beliefs in Writing

In 1905, the Cork National Players performed Alice's play “The Daughter of Donagh.” This play, which the Abbey Theatre had rejected, was based on her unpublished novel "The Cromwellians." It combined the idea of Irish people losing their land with a forbidden relationship between a Cromwellian soldier and the daughter of the Irish family he was staying with.

Alice always included nationalist ideas in her writing. In 1893, she wrote that Irish art couldn't exist "in some quiet paradise apart." It had to be "within the noisy field of political warfare." She criticized writers who focused only on literature and "lacked the national spirit."

Later Years

Before World War I, Alice lived in Dublin with her younger brother William and his family. They wrote two books together: an Irish-Norse story called Sons of the Sea King and The Dynamite Drummer. In the second book, an American tourist comments on how determined Ulster Protestants were against Home Rule. When the war started, William joined the British Army. After he was discharged, he suffered from what we now call Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In late 1921, he was told he had 24 hours to leave Dublin or be shot. Alice left her bookshop and all her belongings and fled with her brother to Belfast, then to England.

Alice and William returned to Northern Ireland in 1931. She lived with William, his wife, and his paralyzed son in a village near Omagh. Her nephew, whom she loved very much, died in 1934 at age 26. William died three years later.

Alice felt like an "interned prisoner" because her mail was often stopped and she had to report to a police station daily. In 1938, she spoke about the "hostile" and "un-Irish" atmosphere in the North at a celebration in Wexford. That year, she was the only woman to sign a paper protesting the division of Ireland.

During the Second World War, after her sister-in-law died, Alice went to live on a farm in County Antrim with her lifelong friend, Eleanor Boyd. Without the burden of caring for sick family members, she wrote poems again for nationalist newspapers. In 1941, the National University of Ireland gave her an honorary doctorate.

Alice Milligan died in Trichur, County Tyrone, on April 13, 1953, at age 87. She died in poverty. She explained that her Unionist relatives didn't want to help her because of her political activities. An Irish writer who visited her in the late 1940s was sad to see her "poor, lonely and smoke-dried" at the end of her life.

In 1914, Tomas MacDonagh said Alice was "a northern Protestant woman who had denounced the unionist Anglo-centric doctrine of her upbringing." He said her work gave a voice to people like her who were often ignored in history.

Commemoration

In 2010/2011, the Ulster History Circle put up plaques for famous people from Ulster. Charlotte Milligan Fox and Alice Milligan have a plaque on Omagh Library in Omagh, County Tyrone.

Select Works

Plays

- “The Last Feast of the Fianna”, Daily Express, Dublin (1899)

- "The Daughters of Donagh", United Irishmen" (weekly, December 1903)

- “Brian of Banba”, in United Irishman (1904)

- “Oisin in Tir-nan-Og”, Daily Express, Dublin (1899)

- “Oisin and Padraic: One-Act Play”, Sinn Féin (20 Feb. 1909)

Plays (Book Form)

- The Last Feast of the Fianna: A Dramatic Legend (London: David Nutt 1900)

- The Daughter of Donagh: A Cromwellian Drama in Four Acts (1905)

Poetry

- Hero Lays (Dublin: Maunsel, 1908)

- Two Poems (Dublin: Three Candles, 1943)

- with Ethna Carbery & Seumus MacManus, We Sang for Ireland (Dublin: Gill, 1950)

- Poems by Alice Milligan, edited by Henry Mangan (Dublin: Gill, 1954)

- The Harper of the Only God: A Selection of Poetry by Alice Milligan, edited by Sheila Turner Johnston (Omagh: Colourpoint, 1993)

Novels

- A Royal Democrat (London: Simpkin, Marshall/Dublin: Gill, 1892)

- "The Cromwellians", (United Irishman, 5–26 Dec. 1903, weekly serialisation)

- with William Milligan, The Dynamite Drummer (Dublin: Lester, [1900] 1918)

- with William Milligan, Sons of the Sea King Dublin (Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son, 1914)

Non-fiction

- with Seaton F. Milligan, Glimpses of Erin: An Account of the Ancient Civilisation, Manners, Customs, and Antiquities of Ireland (London: Marcus Ward, 1890)

- The Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone (Belfast: J. W. Boyd, 1898)

- "Tribute to AE" [George Russell], Dublin Magazine (October 1935)

- Harper of the Only God, selected writing, edited by Sheila Turner Johnston (Newtownards: Colourpoint, 1993)

See Also

- List of Irish writers

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |