American chestnut facts for kids

Quick facts for kids American chestnut |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| American chestnut leaves and nuts | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Castanea |

| Species: |

C. dentata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh.

|

|

|

|

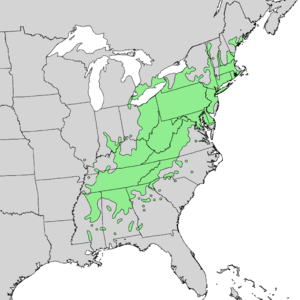

| Natural range of Castanea dentata | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a large deciduous tree. It belongs to the beech family. This tree used to be very important in the forests of eastern North America. Many people thought it was the best chestnut tree in the world.

Sadly, a fungus called chestnut blight almost wiped out the American chestnut. This disease came from chestnut trees brought over from East Asia. It's believed that between 3 and 4 billion American chestnut trees died in the early 1900s because of this blight. Today, very few large American chestnut trees are left in their natural home. However, many small shoots still grow from the roots of old trees. There are also hundreds of large trees outside its original range, like in Northern Michigan, where the disease is not as strong. The American chestnut is now listed as endangered in the United States and Canada.

Chinese chestnut trees are very good at fighting off the chestnut blight. Because of this, scientists are now trying to save the American chestnut. They are cross-breeding (mixing) American chestnuts with blight-resistant Chinese chestnuts. The goal is to give the American chestnut tree the genes it needs to fight the disease. This way, it can hopefully return to being a common tree in American forests.

Contents

What Does the American Chestnut Look Like?

The American chestnut is a fast-growing hardwood tree. In the past, it could grow up to 30 meters (100 feet) tall and 3 meters (10 feet) wide. Its natural home stretched from Maine and southern Ontario down to Mississippi. It grew from the Atlantic coast to the Appalachian Mountains and the Ohio Valley. The American chestnut was once one of the most common trees in the Northeastern United States. In Pennsylvania, it made up about 25–30% of all hardwood trees. This tree was so common because it grew fast and produced many nuts every year. It started making nuts when it was only 7 or 8 years old.

There are other similar chestnut trees, like the European sweet chestnut (C. sativa), Chinese chestnut (C. mollissima), and Japanese chestnut (C. crenata). You can tell the American chestnut apart by its leaf shape, leaf stem length, and nut size. For example, its leaves have larger, more spaced-out saw-teeth on their edges. This is why its scientific name is dentata, which means "toothed" in Latin.

The leaves are about 14–20 cm (5.5–8 in) long and 7–10 cm (3–4 in) wide. The Chinese chestnut, which can resist the blight, is now often planted in the U.S. The European chestnut is where most store-bought nuts come from. You can tell the Chinese chestnut from the American one because its twig tips are hairy, while the American chestnut's twigs are smooth. Chestnuts are in the beech family, along with beech and oak trees. But they are not related to the horse-chestnut, which is a different kind of tree.

The American chestnut tree has both male and female flowers on the same tree. It produces many small, pale green male flowers that grow tightly along long, hanging catkins. The female flowers are found near the base of these catkins. They appear in late spring to early summer. Like all trees in the beech family, American chestnuts need two different trees to pollinate each other. Any tree from the Castanea family can help.

The American chestnut makes many nuts. Usually, three nuts are inside a spiny, green burr. The inside of the burr is lined with soft, tan velvet. The nuts grow during the late summer. The burrs open and fall to the ground around the first frost in autumn.

This tree was very important for wildlife. Its nuts provided a lot of food in the fall for animals like white-tailed deer and wild turkey. Even black bears ate the nuts to get fat for winter. American chestnut leaves also put more good stuff like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium back into the soil than other trees. This helped other plants, animals, and tiny living things grow.

The Chestnut Blight Disease

The American chestnut was once a very important tree for wood. But it suffered a huge population drop because of the chestnut blight. This disease is caused by an Asian fungus called Cryphonectria parasitica. The fungus was accidentally brought to North America on chestnut trees imported from Asia. The chestnut blight was first noticed in 1904 in New York City. By 1906, almost all chestnut trees in that area were infected.

Chinese chestnut trees had grown with this fungus for a long time and developed a strong resistance to it. But the American chestnut had very little protection. The airborne fungus spread about 50 kilometers (30 miles) a year. In just a few decades, it killed up to three billion American chestnut trees. When the main part of a tree dies, new shoots often grow from its roots. So, the species has not completely disappeared. However, these new shoots usually don't grow taller than 6 meters (20 feet) before the blight infects them again. This means the American chestnut is "functionally extinct." It still exists, but it can't grow into a large, mature tree that produces many nuts.

Before the chestnut blight, another disease called ink disease hit American chestnuts in the early 1800s. This fungus, likely from Europe, attacks the tree's roots. It mostly affected chestnuts in the southeastern U.S. So, the American chestnut's range might have already been smaller when the blight arrived.

Why the Population is So Small Now

It's thought that there were over three billion chestnut trees in eastern North America. About 25% of the trees in the Appalachian Mountains were American chestnuts. Today, there are probably fewer than 100 large trees (over 60 cm or 2 feet wide) left in its original home.

Even though large trees are rare east of the Mississippi River, some exist in the western U.S. Settlers took American chestnut seeds with them in the 1800s. Huge planted chestnut trees can be found in Sherwood, Oregon. The dry, warm climate there helps keep the fungus away. American chestnuts also grow well as far north as Revelstoke, British Columbia.

Right now, it's very hard for C. dentata to survive for more than ten years in its native range. The blight fungus can live on different oak trees without harming them. But if an American chestnut is nearby, it will likely get sick and die in about a year. Also, the many old chestnut stumps and roots in eastern forests might still carry the active fungus.

The loss of American chestnuts also affected many insects. About 60 insect species relied on the American chestnut for food. Seven of these species depended only on the American chestnut. Some, like the American chestnut moth, are now extinct.

Trying to Bring Them Back

Many groups are trying to breed chestnut trees that can resist the blight. The American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation breeds American chestnuts that naturally show some resistance. The Canadian Chestnut Council is also trying to bring the trees back to Canada.

Genetically Modified Blight-Resistant American Chestnut

Scientists at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF) have created American chestnuts that can partly resist the blight. They did this by adding a special gene from wheat into the American chestnut's genome (its genetic code). This gene makes a substance called oxalate oxidase. This substance is a common way plants fight fungi. It's found in strawberries, bananas, oats, and other grains. Oxalate oxidase breaks down a harmful acid that the fungus uses to kill tree tissues.

Chestnut trees with this gene can still get infected by the blight. But the tree can heal around the infected area and doesn't die. This allows the fungus to live without killing the tree. The gene for resistance can also be passed down to the tree's babies. In 2020, scientists asked the government for permission to make these trees available to the public. These could be the first genetically modified forest trees released into the wild in the United States.

Japanese chestnut trees (Castanea crenata) can resist ink disease. Scientists are studying how they do this. They hope to use this knowledge to make American chestnuts resistant to ink disease too. If they can combine resistance to both blight and ink disease, it would be a big step forward.

Breeding Surviving American Chestnuts Together

The American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation (ACCF) is trying a different method. Instead of using Asian chestnuts, they are breeding American chestnuts that have survived the blight. They believe there might be several different traits that help trees resist the disease. By breeding resistant American chestnuts from many places, they hope to create a truly strong American chestnut.

Scientists measure how well a tree resists the blight by infecting young trees with the fungus. They then watch how the cankers (sores) grow. Trees with no resistance get large, deep cankers that kill the wood. Resistant trees get smaller, swollen cankers that stay on the surface. This method helps them choose the best trees for breeding.

Backcrossing Method

The The American Chestnut Foundation uses a method called backcrossing. This idea was first suggested in the 1970s. Early attempts to cross-breed American chestnuts with European and Asian chestnuts failed because scientists thought many genes were involved in resistance. It is now believed that only a few genes are responsible.

The backcrossing method involves breeding a blight-resistant Chinese chestnut with an American chestnut. Then, the new hybrid tree is bred with another American chestnut. This process is repeated over several generations. Each time, the new trees get more American chestnut genes, but they keep the blight resistance from the Chinese chestnut. The goal is to create a tree that is almost entirely American chestnut but can still fight off the blight.

The first backcrossed American chestnut tree, named "Clapper," survived the blight for 25 years. Since 1983, parts of this tree have been used by The American Chestnut Foundation. The Pennsylvania chapter of the foundation has planted over 22,000 trees.

Some American chestnut trees have been planted in old coal mines. In 2005, a hybrid tree with mostly American genes was planted on the lawn of the White House. Another tree planted in 2005 near the USDA building was still healthy seven years later. This tree has 98% American chestnut DNA and 2% Chinese chestnut DNA. This small amount of Chinese DNA gives it the resistance it needs.

Hypovirulence (Helping the Tree Fight Back)

A special kind of virus can infect the blight fungus itself. This virus makes the fungus weaker, so it can't harm the chestnut tree as much. This is called hypovirulence. In Europe, this fungal virus spread naturally among European chestnuts. It allowed the trees to recover from the blight and grow large again.

Hypovirulence has also been found in North America, but it hasn't spread as well. The "Arner Tree" in Southern Ontario is a great example. It's a mature American chestnut that recovered from serious blight infections. The cankers healed, and the tree continues to grow strong. Scientists found that the blight on this tree is weak because of the virus. When trees are infected with this weaker blight, the cankers stay on the outside of the tree and don't spread deep inside, helping the tree survive.

Where Are Surviving American Chestnuts Found?

- About 2,500 chestnut trees grow on 60 acres near West Salem, Wisconsin. This is the world's largest group of American chestnuts still alive. These trees are descendants of those planted by an early settler in the late 1800s. Since they were planted outside the chestnut's natural range, they avoided the first wave of blight. But in 1987, blight was found there. Scientists are working to save them.

- Two of the largest surviving American chestnut trees are in Jackson County, Tennessee. One is the state champion, about 61 cm (24 in) wide and 23 meters (75 ft) tall.

- In May 2006, a biologist found a group of trees near Warm Springs, Georgia. One of them is about 20–30 years old and 13 meters (43 ft) tall. It's the southernmost American chestnut known to be flowering and making nuts.

- Another large tree was found in Talladega National Forest, Alabama, in June 2005.

- In the summer of 2007, a group of trees was found near Braceville, Ohio. It includes four large flowering trees, the tallest about 23 meters (75 ft) tall. Many smaller trees are also there. They might have survived because they are somewhat resistant, or because the blight fungus is weaker there, or because they are in a good location, possibly at a higher altitude where spores don't travel as easily.

- In March 2008, officials in Ohio announced they found a rare adult American chestnut tree near Lake Erie. They had kept it a secret for seven years to protect it.

- Members of the Kentucky chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation are pollinating a tree in Adair County and another in Elliott County. The Adair County tree is over 100 years old.

- In June 2007, a mature American chestnut was found in Farmington, New Hampshire.

- In rural Missaukee County, Michigan, a blight-free group of American chestnut trees was found. The largest tree is about 128 cm (50 in) around.

- American chestnuts have also been found on Beaver Island in northern Lake Michigan.

- Hundreds of healthy American chestnuts have been found in the proposed Chestnut Ridge Wilderness Area in the Allegheny National Forest in Pennsylvania. Many are over 60 feet tall.

- The Montreal Botanical Garden has American chestnuts in its collection.

- At least two American chestnuts grow by the Skitchewaug Trail in Springfield, Vermont.

- Around 300 to 500 trees were seen in the George Washington National Forest in Augusta County, Virginia, in 2014.

- Two trees planted in 1985 at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia are doing well. They came from young trees grown in Europe, away from the blight.

- A single mature American chestnut can be found in Sault Ste Marie, Ontario. It was planted in the 1920s and has avoided the blight because it's far north of the chestnut's natural home.

- There is one strong, nut-producing American chestnut in South Centre, Pennsylvania, that has been producing nuts for almost 30 years.

- A single American chestnut tree grows in Wawayanda, New York. It was planted in the early 1990s and has been producing fruit since 2005.

- A perfect American Chestnut tree grows on the Oakdale Campus in Coralville, Iowa.

- Many chestnut trees in the U.S. today come from Dunstan chestnuts, developed in Greensboro, N.C., in the 1960s.

- Multiple chestnut trees are still alive and bearing nuts in Wind River Arboretum, Washington State.

How People Used the American Chestnut

Food and Medicine

The nuts were once a very important food source in North America. They were sold on city streets, especially around Christmas. Chestnuts can be eaten raw or roasted, but most people prefer them roasted. Today, nuts from the European sweet chestnut are often sold in stores instead. You need to peel the brown skin to get to the yellowish-white part inside. The seeds of the unrelated horse-chestnut are poisonous if not prepared carefully.

Native Americans used different parts of the American chestnut to treat illnesses. They used it for things like whooping cough, heart problems, and skin rashes. The nuts were also a common food for many types of wildlife. Farmers even let their livestock, like pigs, roam in the forests to eat the abundant chestnut nuts. The American chestnut tree was important to Native Americans as a food source for both people and animals.

Furniture and Other Wood Products

In 1888, a magazine called Orchard and Garden said the American chestnut wood was "better than any found in Europe." The wood was straight, strong, and easy to cut and split. It was also very valuable because it grew faster than oak trees.

The wood had a lot of tannins, which made it very resistant to rot. Because of this, it was used for many things. These included furniture, split-rail fences, shingles, house building, flooring, and even telephone poles. Tannins were also taken from the bark to tan leather. Even though large trees are no longer available for cutting, a lot of chestnut wood has been reused from old barns to make new furniture and other items.

"Wormy" chestnut refers to wood that has insect damage. This came from trees that died from the blight and were left standing for a long time. This "wormy" wood is now popular because of its unique, rustic look.

The American chestnut is not usually chosen as a good shade tree for patios. This is because it drops a lot of things. In spring, it drops catkins. In fall, it drops spiny nut pods. In early winter, it drops leaves. These things can be a nuisance, especially the spiny seed pods if they are scattered where people walk.

See also

In Spanish: Castaño estadounidense para niños

In Spanish: Castaño estadounidense para niños