Challenger expedition facts for kids

The Challenger expedition was a huge scientific journey that happened from 1872 to 1876. It helped start the study of oceanography, which is the science of oceans. The trip was named after the ship, HMS Challenger.

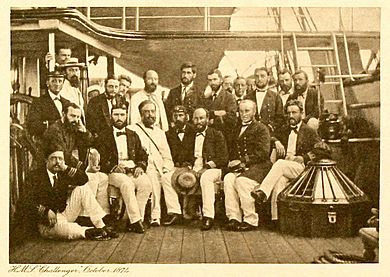

William Benjamin Carpenter started the idea for this expedition. Sir Charles Wyville Thomson, a scientist from the University of Edinburgh, led the scientific team. He had five other scientists, including Sir John Murray, plus an artist and a photographer. The Royal Society of London got the ship Challenger from the Royal Navy. In 1872, they changed the ship to be a floating lab, adding special rooms for studying natural history and chemistry.

Captain George Nares led the expedition. The ship sailed from Portsmouth, England, on December 21, 1872.

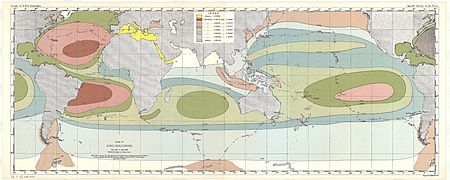

Under Thomson's scientific guidance, the ship traveled about 127,580 kilometers (79,280 miles) around the world. They explored and mapped the oceans. The expedition's findings were published in a huge report. It was called Report of the Scientific Results of the Exploring Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76. This report described over 4,000 new species that had never been seen before!

John Murray, who helped publish the report, said it was the biggest step forward in knowing about our planet since the great discoveries of the 1400s and 1500s. You can find the report online here. The Challenger sailed close to Antarctica. Even though they didn't see the land, it was the first scientific trip to take pictures of icebergs.

Contents

Preparing for the Ocean Journey

To get ready for exploring the deep sea, 15 of the Challenger's 17 guns were taken off. They also reduced its masts and sails to make more room. Special laboratories, extra cabins, and a platform for dredging (scooping up things from the seafloor) were added.

The Challenger mostly used its sails during the trip. The steam engine was only used for pulling the dredge, staying still while measuring depth, and entering or leaving ports. The ship was packed with many tools:

- Jars filled with alcohol to keep samples safe

- Microscopes and chemistry tools

- Nets and dredges for collecting sea creatures

- Thermometers and barometers

- Bottles for collecting water samples

- Heavy leads for measuring ocean depth

- Long ropes to lower equipment deep into the ocean

Because this was a new kind of expedition, some of the equipment was invented or changed just for this trip. For example, they carried 291 kilometers (181 miles) of Italian hemp rope for measuring depths!

The Amazing Expedition

During its famous journey around the world, the crew did a lot of scientific work:

- They took 492 deep sea soundings (depth measurements).

- They did 133 bottom dredges (scooping up samples from the seafloor).

- They performed 151 open water trawls (dragging nets through the water).

- They made 263 measurements of water temperature at different depths.

About 4,700 new species of marine life were discovered!

The main scientists on board were Wyville Thomson, John Murray, John Young Buchanan, Henry Nottidge Moseley, and Rudolf von Willemoes-Suhm. John James Wild was the official artist.

The ship started with 21 officers and about 216 crew members. By the end of the trip, this number was smaller due to some deaths, people leaving, or getting sick.

The Challenger arrived in Hong Kong in December 1874. At this point, Captain Nares left to join another expedition. Frank Tourle Thomson became the new captain. Commander John Maclear was the most senior officer who stayed for the whole journey. Sadly, Willemoes-Suhm died during the trip to Tahiti and was buried at sea.

The first part of the expedition took the ship from Portsmouth (December 1872) to Lisbon (January 1873), then to Gibraltar. Next, they stopped at Madeira and the Canary Islands (February 1873). From February to July 1873, they crossed the Atlantic Ocean. They went from the Canary Islands to the Virgin Islands, then north to Bermuda, east to the Azores, back to Madeira, and then south to the Cape Verde Islands.

After leaving the Cape Verde Islands in August 1873, they sailed southeast and then west to St Paul's Rocks. From there, they went south across the equator to Fernando de Noronha and then to Bahia in Brazil. From September to October 1873, they crossed the Atlantic from Bahia to the Cape of Good Hope, stopping at Tristan da Cunha.

From December 1873 to February 1874, they sailed southeast from the Cape of Good Hope towards 60 degrees south latitude. They visited islands like the Prince Edward Islands, Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Islands, and Heard Island. In February 1874, they traveled south and then east near the Antarctic Circle, seeing icebergs and whales. The ship then headed northeast, away from the ice, reaching Melbourne, Australia, in March 1874. They sailed along the coast from Melbourne to Sydney in April 1874.

The voyage continued in June 1874, heading east from Sydney to Wellington, New Zealand. Then they made a big loop north into the Pacific, stopping at Tonga and Fiji. By the end of August, they were back in Australia at Cape York.

For the next three months, from September to November 1874, the expedition visited several islands. They sailed from Cape York to China and Hong Kong. They explored islands like the Aru Islands, Kai Islands, Banda Islands, Ambon Island, and Ternate Island. These islands are now part of Indonesia.

From Ternate, they sailed northwest towards the Philippines. They stopped at Zamboanga on Mindanao and Iloilo on Panay. Then they sailed to Manila on Luzon. The journey from Manila to Hong Kong happened in November 1874.

After spending weeks in Hong Kong, the expedition left in January 1875. They sailed southeast back towards New Guinea, stopping again in Manila and Zamboanga.

Challenger then headed east into the open sea, turning southeast to land at Humboldt Bay (now Yos Sudarso Bay) on the north coast of New Guinea. By March 1875, they reached the Admiralty Islands northeast of New Guinea. The final part of this Pacific journey was a long trip north, passing west of the Caroline Islands and Mariana Islands. They reached Yokohama, Japan, in April 1875.

The Challenger left Japan in mid-June 1875. They sailed east across the Pacific, then turned south to reach Honolulu on the Hawaiian island of Oahu in late July. A few weeks later, they sailed southeast to Hilo Bay off Hawaii's Big Island. Then they continued south, reaching Tahiti in mid-September.

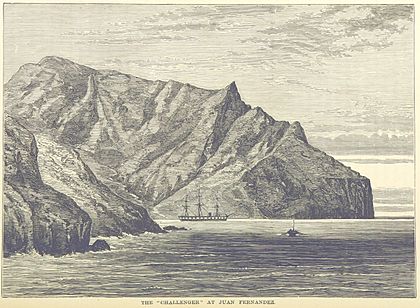

The expedition left Tahiti in early October, heading west and south of the Tubuai Islands. Then they turned southeast before heading east towards South America. They stopped at the Juan Fernández Islands in mid-November 1875, reaching Valparaiso in Chile a few days later. The next part of the journey started the following month. They sailed southwest back into the Pacific, past the Juan Fernández Islands, then southeast back towards South America. They reached Port Otway in the Gulf of Penas on December 31, 1875.

Most of January 1876 was spent sailing around the southern tip of South America. They explored many bays and islands in the Patagonian area, the Strait of Magellan, and Tierra del Fuego.

The final stops before heading into the Atlantic were Port Famine, Sandy Point, and Elizabeth Island. The Challenger reached the Falkland Islands in late January, stopping at Port Stanley. Then they continued north, reaching Montevideo in Uruguay in mid-February 1876. The ship left Montevideo at the end of February, sailing east and then north. They arrived at Ascension Island at the end of March 1876.

From early to mid-April, they sailed from Ascension Island to the Cape Verde Islands. From there, in late April and early May 1876, they made a loop west into the mid-Atlantic. Finally, they turned east towards Europe, reaching Vigo in Spain in late May. The last part of the journey took the ship northeast from Vigo, around the Bay of Biscay, to England. The Challenger returned to Spithead, Hampshire, on May 24, 1876. The ship had spent 713 days at sea out of the 1,250 days it was away.

What the Scientists Wanted to Learn

The Royal Society set out the main goals for the voyage:

- To study the deep sea in the big ocean basins, even near the Great Southern Ice Barrier. They wanted to know about depth, temperature, water movement, how dense the water was, and how far light reached.

- To find out what chemicals were in seawater at different depths, from the surface to the bottom. They also looked for tiny bits of living matter.

- To understand what the deep-sea floor was made of and where these materials came from.

- To learn about how living things were spread out at different depths and on the deep seafloor.

One important goal was to test a theory by Carpenter. He thought that ocean temperature and global ocean currents were linked. This study continued earlier missions by ships like HMS Lightning (1823) and HMS Porcupine (1844). The results were important for Carpenter because his ideas were different from another famous oceanographer, Matthew Fontaine Maury.

Another key reason for collecting data about the ocean floor was for laying underwater telegraph cables. Many cables were being laid in the 1860s and 1870s. Knowing about the seafloor helped lay them correctly and keep them working.

At each of the 360 stops, the crew measured the depth of the ocean floor. They also took temperatures at different depths, watched the weather, and collected samples of the seafloor, water, and living things. The Challenger crew used methods developed on earlier, smaller trips. To measure depth, they lowered a line with a weight until it hit the bottom. The line had marks every 46 meters (25 fathoms). So, their depth measurements were accurate to about 46 meters. The weight often had a small container to collect samples of the bottom sediment.

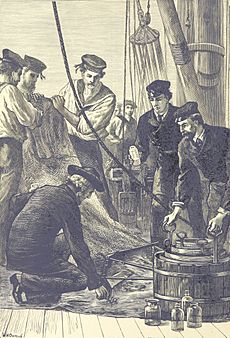

The crew used different types of dredges and trawls to collect living samples. Dredges were metal nets dragged along the seafloor. Mop heads on the dredge would stir up organisms for the nets to catch. Trawls were large metal nets pulled behind the ship to collect organisms at different water depths. After pulling up a dredge or trawl, the crew would sort, clean, and store the specimens. They often kept them in salty water or alcohol to preserve them.

The main thermometer used was the Miller–Casella thermometer. It had two markers to record the highest and lowest temperatures. Several of these were lowered at different depths. However, this thermometer assumed that surface water was always warmer than deep water. During the voyage, the crew tested the reversing thermometer, which could measure temperature at specific depths. This type of thermometer was used widely for many years after the expedition.

Scientists like William Dittmar studied the makeup of seawater. Murray and Alphonse François Renard mapped the sediments on the ocean floor.

Some scientists, like Thomson, believed that the deep sea would be home to "living fossils." These were thought to be creatures that had died out in shallower waters but survived in the stable, cold, dark deep ocean. However, they didn't find many such creatures. While some organisms thought to be extinct were found, the discoveries were similar to what you might find exploring any new area.

Discovering the Challenger Deep

On March 23, 1875, at a spot in the southwest Pacific Ocean between Guam and Palau, the crew measured a depth of 8,184 meters (4,475 fathoms). This was confirmed by another measurement. Later expeditions with modern equipment showed this area is the southern end of the Mariana Trench. It is one of the deepest known places on the ocean floor.

Today, modern measurements have found depths of up to 10,994 meters (36,070 feet) near where the Challenger made its discovery. The Challenger's finding of this extreme depth was a key discovery. It greatly increased our knowledge about the ocean's depth. This deepest part of the ocean is now named the Challenger Deep after the ship.

The expedition also confirmed that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a huge underwater mountain range, stretches from the southern to the northern hemisphere.

The Expedition's Lasting Impact

The findings from the Challenger expedition were published for many years, until 1895. This was 19 years after the journey ended! The report filled 50 volumes and was over 29,500 pages long. The specimens brought back by Challenger were sent to top experts around the world for study. This made the report take a long time and cost a lot.

The report and specimens were shown at the British Natural History Museum in 2023. Some of these specimens were the first of their kind ever discovered. Scientists still study them today.

Many scientists worked on sorting and naming the materials from the expedition. A species of lizard, Saproscincus challengeri, was named after the Challenger by George Albert Boulenger.

Before the Challenger expedition, people mostly guessed about oceanography. The Challenger expedition was the first real oceanographic trip. It created the foundation for an entire field of science and research. The name "Challenger" has been used for many things since, like the Challenger Society for Marine Science, the research ship Glomar Challenger, and even the Space Shuttle Challenger.

|

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |