Economics of English towns and trade in the Middle Ages facts for kids

The economics of English towns and trade in the Middle Ages covers the money and business side of English towns and trade from the Norman invasion in 1066 until 1509. Even though England was mostly about farming back then, buying and selling goods was already important. After the Norman invasion, new rules were put in place, but towns and international trade continued to thrive.

Over the next five centuries, England's economy first grew a lot, then faced a big crisis. This led to major changes in how money worked and how people lived. Despite some tough times in towns, their economic activity grew stronger. By the end of this period, England had a growing economy with many English merchants and trading groups.

Contents

Norman Invasion and Early Years (1066–1100)

William the Conqueror took over England in 1066 after winning the Battle of Hastings. This brought England under Norman rule. William's government was based on a system where land was given in exchange for service to the king. However, the invasion didn't change the English economy much at first. Most of the damage was in the north and west. Many parts of England's trading and money system stayed the same.

Trade, Factories, and Towns

Even though England was mostly rural, it had important towns in 1066. A lot of trade happened through Eastern towns like London, York, Winchester, Lincoln, and Norwich. They traded with France, the Low Countries, and Germany. Some trade from the North-East even reached Sweden. Cloth was already being brought into England before the invasion.

Some towns, like York, were damaged by the Normans. Other towns, like Lincoln, had houses pulled down to build new castles. The Norman invasion also brought the first Jews to English cities. William I brought wealthy Jews from Normandy to London to help with money matters for the king. In the years after the invasion, a lot of wealth went from England to Normandy, making William very rich.

Making coins was spread out in the Saxon period. Every main town had a mint, which was a place for trading metal. But the king had strict control over these coin makers. William kept this system and made sure the coins were of high quality. This is why Norman silver coins were called sterling.

Government and Taxes

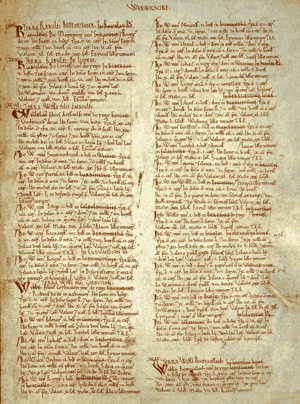

William I continued the Anglo-Saxon system of collecting money. The king got income from customs duties, profits from making new coins, fines, and his own lands. He also used the English land tax called the geld. William made sure this system worked, using his new sheriffs to collect the geld and increasing taxes on trade. William also ordered the creation of the Domesday Book in 1086. This huge document recorded the economic state of his new kingdom.

Growth in the Middle Ages (1100–1290)

The 12th and 13th centuries were a time of huge economic growth in England. The population grew from about 1.5 million in 1086 to around 4 or 5 million by 1300. This led to more farming and more raw materials being sent to Europe. England was also safer from invasions during this time. Most wars had only small or temporary economic effects.

Trade, Manufacturing, and Towns

How English Towns Grew

After a period of unrest, the number of small towns in England grew quickly. By 1297, 120 new towns had been started. By 1350, there were about 500 towns in England. Many of these new towns were carefully planned. For example, Richard I started Portsmouth, and John founded Liverpool. These new towns were usually built near trade routes, not just for defense. Their streets were designed to make it easy to reach the town's market. More and more people lived in towns, rising from about 5.5% in 1086 to 10% in 1377.

London was very important to England's economy. Rich people bought many fancy goods and services there. By the 1170s, London markets offered exotic items like spices, silks, and furs. London was also a center for making things. It had many blacksmiths making various goods, including early clocks. Pewter-working, using English tin and lead, was also common in London. Other towns also had many different jobs. A large town like Coventry had over 300 different specialist jobs. The growing wealth of the rich and the church led to many cathedrals and other grand buildings being built in larger towns. These used lead from English mines for roofs.

Moving goods by land was much more expensive than by river or sea. Many towns, like York and Exeter, were connected to the sea by rivers. They could act as seaports. Bristol's port became very important for trading wine with Gascony by the 13th century. Groups of carriers ran carting businesses, and brokers in London connected traders with carters. They used four main land routes across England. Many bridges were built in the 12th century to improve trade.

In the 13th century, England mainly sent raw materials to Europe, not finished goods. There were a few exceptions, like high-quality cloths from Stamford and Lincoln. Despite royal efforts, very little English cloth was exported by 1347.

More Money in Circulation

Fewer places were allowed to make coins over time. By Edward I's reign, there were only nine mints outside London. The king created a new official called the Master of the Mint to oversee them. The amount of money in circulation grew hugely. Before the Norman invasion, there was about £50,000 in coins. By 1311, this was over £1 million. This meant many coins had to be made and moved in barrels and sacks. Prices generally increased a lot during this century. As a result, the real value of wages went down.

The Rise of Guilds

The first English guilds appeared in the early 12th century. These were groups of craftsmen who managed their local businesses. They set prices, checked quality, and looked after their workers. Some early guilds were "guilds merchants," who ran town markets. Others were "craft guilds," for specific trades like weavers or fullers. More guilds were created over time. By the 14th century, conditions changed. In London, the old guild system started to break down. More trade was happening across the country, and there were bigger differences in wealth among craftsmen. So, under Edward III, many guilds became "companies" or livery companies. These focused on trade and money, while the guild structures looked after smaller manufacturers.

Merchants and Charter Fairs

This period also saw the growth of charter fairs in England, which were most popular in the 13th century. From the 12th century, many English towns got permission from the king to hold an annual fair. These usually served local customers and lasted a few days. Between 1200 and 1270, over 2,200 charters were given for markets and fairs. Fairs became more popular as the international wool trade grew. They allowed English wool producers to meet foreign merchants directly, avoiding middlemen in London. Rich people also used fairs to buy goods like spices and foreign cloth in bulk.

Some fairs became major international events. For example, the St Ives' Great Fair attracted merchants from Flanders, Norway, and Germany for four weeks each year. By 1273, only one-third of the English wool trade was controlled by English merchants. Italian merchants dominated between 1280 and 1320, but German merchants became strong competitors. The Germans formed a group in London called the "Hanse of the Steelyard". In response, the Company of the Staple was created in Calais in 1314. This group had a monopoly on wool sales to Europe.

Jewish People's Role in the Economy

The Jewish community in England provided important money lending and banking services. These services were otherwise banned by laws against charging interest (called usury). The Jewish community grew in the 12th century and spread to major English cities, especially trading hubs with mints. These cities also had castles for protection, as Jewish people were often treated badly. By the time of Stephen, these communities were doing well and lending money to the king.

Under Henry II, the Jewish financial community became even richer. Henry II used them to collect money for the Crown and protected them. The Jewish community in York lent a lot of money to help the Cistercian order buy land. Some Jewish merchants became extremely wealthy.

By the end of Henry's reign, the king stopped borrowing from the Jewish community. Instead, he started taxing them heavily. Violence against Jewish people grew under Richard I. After a terrible event in York where many financial records were destroyed, special places were set up to store Jewish financial documents. This led to the Exchequer of the Jews. John also took money from the Jewish community. During the First Barons' War (1215–1217), Jewish people faced more attacks. Henry III brought some order back, and Jewish money-lending became successful enough for new taxes. However, the Jewish community became poorer towards the end of the century. Finally, Edward I expelled them from England in 1290. Foreign merchants largely took their place.

Government and Taxes

In the 12th century, Norman kings tried to make the feudal system more formal. The king got money from his own lands, the old geld tax, and fines. But kings needed more money, especially for soldiers. They started using the French feudal aid model, which was a money payment from feudal lords when needed. Another method was scutage, where military service could be paid for with cash. Taxes were also an option, but the old geld tax was not working well. Kings created new land taxes, like the tallage and carucage taxes. These were not popular and, along with feudal charges, were limited by the Magna Carta in 1215. To make royal finances more organized, Henry I created the Chancellor of the Exchequer. This led to the keeping of the Pipe rolls, important records for historians.

Royal money was still not enough. From the mid-13th century, taxes shifted from land to a mix of indirect and direct taxes. Henry III of England also started asking leading nobles for advice on tax issues. This led to the English parliament agreeing on new taxes. In 1275, the "Great and Ancient Custom" began taxing wool and hides. In 1303, extra taxes were put on foreign merchants. The poundage tax was introduced in 1347. In 1340, the unpopular tallage tax was finally stopped by Edward III.

In English towns, people paid cash rents for their properties instead of working for them. Towns could also raise taxes for things like building walls (murage), paving streets (pavage), or repairing bridges (pontage). These rules, along with trading laws, helped manage the towns' economies.

The 12th century also saw efforts to limit the rights of unfree peasant workers. Their labor payments were made clearer in English Common Law. The Magna Carta allowed landowners to handle legal cases about feudal labor and fines in their own local courts, not royal courts.

Big Economic Crisis: Famine and Black Death (1290–1350)

The Great Famine

The Great Famine began a series of big problems for England's farming economy. It was caused by bad harvests in 1315, 1316, and 1321. There was also a sickness among sheep and oxen, and a fungus on wheat. Many people died during the famine. People were said to have eaten horses, dogs, and cats, though some reports might be exaggerated. Poaching in royal forests increased a lot. Sheep and cattle numbers fell by half, meaning less wool and meat. Food prices almost doubled, especially grain. Prices stayed high for the next ten years. Salt prices also went up due to wet weather.

Several things made the crisis worse. Economic growth had already slowed before the famine. Many peasants didn't have enough land to live securely. Bad weather, like heavy rains and cold winters, badly affected harvests. Disease was also common. The start of the Hundred Years War with France in 1337 added to the problems. The Great Famine stopped the population growth of the 12th and 13th centuries. It left the economy "deeply shaken, but not destroyed."

The Black Death

The Black Death epidemic first arrived in England in 1348. It came back in waves in 1360–1362, 1368–1369, 1375, and less often after that. The biggest impact was the huge loss of life. About 27% of rich people died, and 40–70% of peasants died. Few towns were completely abandoned, but many were badly affected. The authorities tried to respond, but the economy was greatly disrupted. Building work stopped, and many mines paused. At first, authorities tried to control wages and keep working conditions the same as before the epidemic. But coming after years of famine, the long-term effects were huge. England's population would not recover for over a century. This crisis greatly affected farming, wages, and prices for the rest of the Middle Ages.

Late Medieval Economic Recovery (1350–1509)

The crises between 1290 and 1348, and the later epidemics, created many challenges for England's economy. After the Black Death, economic and social problems, combined with the costs of the Hundred Years War, led to the Peasants Revolt of 1381. Even though the revolt was put down, it weakened the old feudal system. The countryside became dominated by farms, often owned or rented by the new class of rich landowners called the gentry. England's farming economy remained slow throughout the 15th century. Growth came from the greatly increased English cloth trade and manufacturing. The effects of this varied by region. Generally, London, the South, and the West became richer, while the East and older cities declined. The role of merchants and trade became more important to the country. Charging interest on loans became more accepted.

Government and Taxes

Even before the Black Death ended, authorities tried to stop wages and prices from rising. Parliament passed emergency laws like the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349 and the Statute of Labourers in 1351. Efforts to control the economy continued as wages and prices went up, putting pressure on landowners. In 1363, parliament tried to control craft production and trade, but it didn't work. More and more of the royal courts' time was spent trying to enforce these failing labor laws. Many landowners tried to force peasants to pay rents with farm work instead of money. This led to many villages trying to challenge feudal practices using the Domesday Book as proof. Since wages for lower classes were still rising, the government also tried to control what people bought and wore. They brought back sumptuary laws in 1363. These laws stopped lower classes from buying certain products or wearing fancy clothes. This showed how important high-quality food, drink, and fabrics were for showing social class.

In the 1370s, the government also struggled to pay for the war with France. The impact of the Hundred Years War on England's economy is debated. Some think high taxes "shrunk and depleted" the economy, while others say it had a smaller or neutral effect. The English government found it hard to pay its army. From 1377, they started using new poll taxes, which aimed to spread the cost of taxes across all of English society.

The Peasants' Revolt of 1381

One result of the economic and political tensions was the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. This involved widespread anger in the countryside, followed by thousands of rebels invading London. The rebels had many demands. These included ending the feudal system of serfdom and putting a limit on rural rents. The violence surprised the ruling class. The revolt was not fully stopped until the autumn, and up to 7,000 rebels were executed. Because of the revolt, parliament stopped the poll tax. Instead, they focused on indirect taxes, mostly on foreign trade. About 80% of tax money came from wool exports. Parliament continued to collect high direct taxes until 1422, but they decreased later. As a result, kings found their tax money uncertain. Henry VI had less than half the annual tax money of the late 14th century. England's kings became more dependent on borrowing money. They even faced later rebellions over taxes, like the Yorkshire rebellion of 1489 and the Cornish rebellion of 1497 during Henry VII's reign.

Trade, Manufacturing, and Towns

Shrinking Towns

The percentage of England's population living in towns continued to grow. But in actual numbers, English towns shrunk a lot because of the Black Death. This was especially true in the East, which used to be rich. The importance of England's Eastern ports declined. Trade from London and the South-West became more important. More detailed road networks were built across England, some with many bridges. However, it was still cheaper to move goods by water. Timber was brought to London from as far as the Baltic Sea, and stone from France came across the Channel to the South of England. Shipbuilding, especially in the South-West, became a major industry for the first time. Investing in trading ships like cogs was probably the biggest type of investment in late medieval England.

The Rise of the Cloth Trade

Cloth made in England became very popular in European markets during the 15th and early 16th centuries. England exported almost no cloth in 1347. But by 1400, about 40,000 cloths were exported each year. This reached a peak of 60,000 in 1447. Trade fell during a tough period in the mid-15th century. But it picked up again, reaching 130,000 cloths a year by the 1540s. The main areas for weaving in England shifted westwards, away from older centers like York and Norwich.

The wool and cloth trade was now mostly run by English merchants, not foreigners. More and more, trade went through London and the South-West ports. By the 1360s, English merchants controlled 66 to 75% of the export trade. By the 15th century, this was 80%. London handled about 50% of these exports in 1400, and up to 83% by 1540. The number of trading companies in London, like the Worshipful Company of Drapers, continued to grow. English producers started giving credit to European buyers. Charging interest on loans became more common, with few cases being punished.

There were some setbacks. English merchants' attempts to trade directly with the Baltic region failed during the Wars of the Roses in the 1460s and 1470s. The wine trade with Gascony fell by half during the war with France. The loss of Gascony ended English control of that business. This temporarily hurt Bristol's wealth until Spanish wines started coming through the city. The problems with Baltic and Gascon trade led to less consumption of furs and wine by English rich people in the 15th century.

Manufacturing improved, especially in the South and West. Despite some French attacks, the war created wealth along the coast due to huge spending on shipbuilding. The South-West also became a center for English piracy against foreign ships. Metalworking continued to grow. Pewter working, in particular, generated exports second only to cloth. By the 15th century, pewter working was a big industry in London, with a hundred pewter workers there. It had also spread to eleven other major cities. London goldsmithing remained important but didn't grow much. Iron-working continued to expand. In 1509, the first cast iron cannon was made in England. This was seen in the fast growth of iron-working guilds, from three in 1300 to fourteen by 1422.

This led to a lot of money coming into England. This money encouraged the import of fancy manufactured goods. By 1391, shipments from abroad regularly included "ivory, mirrors, armor, paper, painted clothes, spectacles, tin images, razors, calamine, treacle, sugar-candy, marking irons, and quantities of wainscot". Imported spices were now part of almost all noble and gentry diets. The English government also imported large amounts of raw materials, like copper, for making weapons. Many rich landowners focused on maintaining one main castle or house, rather than dozens as before. But these were usually decorated much more luxuriously. Major merchants' homes were also more lavish.

Decline of the Fair System

Towards the end of the 14th century, fairs started to decline. Larger merchants, especially in London, began to deal directly with big landowners like nobles and the church. Instead of buying from a chartered fair, landowners would buy directly from the merchant. Also, the growth of English merchants in major cities, especially London, gradually pushed out the foreign merchants that the great chartered fairs depended on. The king's control over trade in towns became weaker. This was especially true for newer towns in the late 15th century that lacked strong local governments. This made chartered status less important as more trade happened from private properties all year round. Still, the great fairs remained important well into the 15th century for exchanging money, regional trade, and offering choices to individual buyers.

See also

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |