Gristmill facts for kids

A grist mill is a special building or machine that grinds grain (like wheat or corn) into flour or meal. Imagine a big blender for grains! Most old grist mills used the power of water to work. They had a large waterwheel and two big stones for grinding. The water pushed the wheel, making it spin. This spinning motion turned an axle (a rod) inside the mill. The axle was connected to gears, which made the grinding stones spin. Grain would slowly fall from a chute into these spinning stones, getting crushed into flour. Some old grist mills also used windmills instead of water.

Contents

History of Grist Mills

Early Mills

People have been grinding grain for thousands of years. The first water-powered grist mills in Europe were built around 200 BC. One of the earliest descriptions of a mill was in 63 BC, found in a place called Cabira. These very first mills had wheels that spun flat (horizontally).

Later, by the end of 100 BC, the Roman Empire started using mills with wheels that spun upright (vertically). A famous Roman writer named Vitruvius described these. A great example of Roman mill technology was the Barbegal mill in France. It used water falling 19 meters to power sixteen water wheels! This mill could grind about 2.4 to 3.2 tons of grain every hour.

Water mills continued to be used after the Roman Empire. By 1000 AD, mills in Europe were very common, often just a few miles apart. In England, a survey from 1086 called the Domesday Book counted 5,624 water-powered flour mills. That's about one mill for every 300 people! This shows how important mills were for daily life. Over time, water wheels started to be used for other jobs too, not just grinding grain. By 1300, the number of mills in England grew to about 17,000.

Some old grist mills from the High Middle Ages can still be seen today. For example, there's a well-preserved waterwheel and grist mill on the Ebro River in Spain. It was built by Cistercian monks in 1202. These monks were well-known for using this technology in Western Europe between 1100 and 1350.

How Traditional Mills Worked

Most traditional grist mills were powered by water, but some used wind or even livestock. To start a water mill, a sluice gate would be opened. This allowed water to flow into a channel and turn the water wheel. Most water wheels were mounted vertically (upright), but some spun horizontally. Later, some mills were updated with horizontal steel or cast iron turbines.

In most mills with a vertical water wheel, a large gear called the pit wheel was attached to the same axle as the water wheel. This pit wheel turned a smaller gear called the wallower. The wallower was on a main driveshaft that went straight up through the building. This system made the main shaft spin much faster than the water wheel, which usually turned at about 10 rpm.

The millstones themselves spun much faster, around 120 rpm. There were two stones: the bottom one, called the bed, was fixed to the floor. The top stone, called the runner, was mounted on a separate spindle, which was turned by the main shaft. A wheel called the stone nut connected the runner's spindle to the main shaft. This stone nut could be moved to stop the runner stone from turning, allowing the main shaft to power other machines. These other machines might include a mechanical sieve to make the flour finer, or a wooden drum to hoist sacks of grain to the top of the mill.

Here's how the grain moved through the mill:

- Grain was lifted in sacks to the sack floor at the very top of the mill.

- The sacks were emptied into bins.

- From the bins, the grain fell down through a hopper to the grinding stones on the stone floor below.

- The amount of grain flowing was controlled by shaking it along a gently sloping trough (called the slipper).

- The grain then fell into a hole in the center of the runner stone.

- As the stones ground the grain, the milled flour came out through grooves on the outer edge of the stones.

- The flour then went down a chute and was collected in sacks on the ground or meal floor.

This process was used for grains like wheat and kamut to make flour, and for maize to make corn meal.

To stop the mill's vibrations from shaking the building apart, grist mills often had at least two separate foundations.

An American inventor named Oliver Evans changed this process a lot. In the late 1700s, he created and patented a fully automated mill design. This meant less human labor was needed.

The Boykin Mill in Boykin, South Carolina, is still working today. It has been grinding meal and grits using water power for over 150 years!

Modern Mills

In the past, grist mills used spinning stones powered by water or wind. Later, some mills started using steam engines for power. Today, most modern mills use electricity or fossil fuels to spin heavy steel rollers. These newer methods create flour that looks a bit different, but it can be just as healthy and useful.

Grist mills only grind clean grains. This means the stalks and chaff (the outer husks) have already been removed. However, some mills also had machines to thresh (separate the grain), sort, and clean the grain before grinding. Grist mills also grind corn into corn meal.

Most modern mills are "merchant mills." This means they are owned by companies that buy unmilled grain and then sell the flour they produce. In the past, mills were often built and supported by farming communities. Farmers would bring their own grain, and the miller would take a small percentage of it, called a "miller's toll," instead of being paid wages. While "gristmill" can mean any mill that grinds grain, the term historically referred to these local mills where farmers brought their own grain and received their flour back, minus the miller's toll.

Modern mills use special serrated and flat cast iron rollers. These rollers separate the bran and germ from the endosperm. The endosperm is then ground to make white flour. Sometimes, the bran and germ are added back in to create whole wheat or graham flour.

Images for kids

-

Modern mills are highly automated. This is the inside of Tartu Mill, the biggest grain milling company in the Baltic states.

-

Phelps Mill in Otter Tail County.

-

Allied Mills flour mill on the banks of the Manchester Ship Canal.

-

Senenu Grinding Grain, around 1352–1336 B.C. This old sculpture shows the royal scribe Senenu grinding grain. It might be a type of shabti, a small statue placed in a tomb to do work for the person who died. From the Brooklyn Museum.

-

Stretton Watermill, a working mill from the 1600s in Cheshire, England.

-

The Pilgrim's Pride feed mill in Pittsburg, Texas, in August 2015.

-

A gristmill hopper on Skyline Drive, VA, 1938. Grain was funneled through this hopper to a grinding stone below.

-

The machinery that drives the gristmill in the basement of Thomas Mill, Chester County, PA.

-

A wheat mill powered by pedals, from Shediac Cape, New Brunswick.

-

What's left of some of the many flour mills built in Minneapolis between 1850 and 1900. Notice the underground Mill race that powered mills on the west side of the Mississippi River at St. Anthony Falls.

-

The wheel of the 1840s-era Grist Mill at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA.

-

The "slipper" feeding corn into the grindstones at George Washington's Gristmill.

-

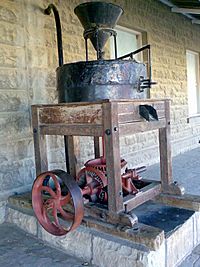

An old turbine wheel at the old grist mill in Thorp, Washington.

-

The grist mill at the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts.

-

A grist mill at Jarrell Plantation, acquired in 1899.

See also

In Spanish: Molino de grano para niños

In Spanish: Molino de grano para niños