History of Belfast facts for kids

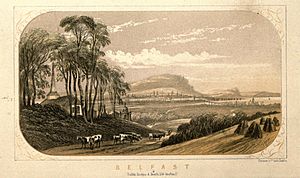

The history of Belfast as a city began a very long time ago, during the Iron Age. However, it really grew into a big city in the 1700s. Today, Belfast is the capital of Northern Ireland. For a long time, it was a major center for business and industry, especially shipbuilding. In recent years, some of its older industries have become smaller.

Belfast's history has also seen a lot of conflict between Catholic and Protestant communities. This led to many areas of the city becoming separated into Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. Luckily, the city has been much more peaceful recently, and many parts of the city, especially the center and the dock areas, have been rebuilt and improved.

Contents

Early Settlements and Castles

The area around Belfast has been lived in for a very long time, even since the Bronze Age. For example, the Giant's Ring, a huge stone circle built 5,000 years ago, is located near the city. People have also found signs of Bronze and Iron Age settlements in the hills nearby, like McArt's Fort, an Iron Age hill fort on top of Cavehill.

The first settlement in Belfast was quite small, like a village. It was built around a marshy crossing point where the River Lagan met the River Farset. Today, this area is where High Street meets Victoria Street. This crossing, known as the Ford of Belfast, was important as early as 665 AD, when a battle was fought there. The Church of Ireland church called St. George's now stands where an old chapel used to be, which was used by travelers crossing the water.

To protect this important crossing, the English built a castle. It was located where Castle Place is now, a busy spot where several roads meet. This castle was attacked, captured, destroyed, and rebuilt many times. For example, it was destroyed in 1315 by Edward le Bruce and again in 1503 by Gerald Mór FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare. The old Belfast Castle was finally destroyed by fire in 1708.

In 1612, King James gave the town of Belfast and its castle, along with large areas of land, to Sir Arthur Chichester. This made Belfast more important. In 1613, Belfast became a corporation, which meant it could govern itself more and send two people to parliament.

Even with this new importance, Belfast was still a small place. Nearby Carrickfergus was a much bigger and more important trading center. However, in 1640, Belfast gained special trading rights that had belonged to Carrickfergus. This helped Belfast grow quickly, while Carrickfergus became less important.

Throughout the 1600s, many English and Scottish settlers moved to Belfast as part of the Plantation of Ulster. After the 1641 Rebellion, many Scottish soldiers who came to put down the unrest also settled in Belfast.

During the Williamite War in Ireland, Belfast changed hands a couple of times. It was first taken by Protestants who were against the rule of the Catholic King James II. Then, it was captured by the mainly Catholic Irish Army. Later that same year, a large army led by Williamite forces arrived and took Belfast without a fight. Belfast remained under Williamite control until the end of the war.

Belfast: A City of Trade and Industry

In the 1700s, Belfast grew into a busy trading town. It imported goods from Great Britain and exported linen, which was made by many small producers in the countryside. Belfast also became a center for new political ideas. Many of its people were Presbyterian, and they faced unfair rules, which made them want change. Ideas from the Scottish Enlightenment also influenced the city.

Belfast saw the start of groups like the Irish Volunteers in 1778 and the Society of United Irishmen in 1791. Both groups wanted democratic changes, an end to religious unfairness, and more independence for Ireland. However, due to strong government control, people from Belfast didn't play a big role in the Irish rebellion of 1798.

Two big changes happened in Belfast's city center around this time. In 1784, plans were made for the White Linen Hall (where Belfast City Hall is now) and new modern streets like Donegall Square. Also, in 1786, the River Farset was covered over to create High Street.

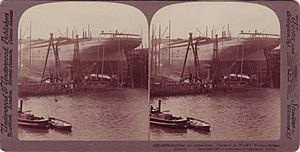

In the 1800s, Belfast became Ireland's most important industrial city. Industries like linen, heavy engineering, tobacco, and shipbuilding were very strong. Belfast was a perfect place for shipbuilding because it was located at the end of Belfast Lough and at the mouth of the River Lagan. The Harland and Wolff company was a huge shipbuilding company that employed up to 35,000 workers and was one of the largest in the world. The famous RMS Titanic was built there in 1911.

Many people moved to Belfast from all over Ireland, Scotland, and England, especially from rural areas of Ulster. This led to more tensions between different groups. During this time, the first serious outbreaks of violence between Catholic and Protestant communities happened, and these unfortunately continued for many years.

For example, in 1829, parades by the Orange Institution were banned, leading to riots and deaths. In 1857, fights between Catholic and Protestant crowds turned into ten days of rioting. In 1886, celebrations after a political vote led to more riots and deaths.

In the second half of the 1800s, Belfast changed a lot. It grew much larger than Carrickfergus, and even Carrickfergus Lough was renamed Belfast Lough. Many industries moved to Belfast, causing a lot of people to move into the city. Many of these new residents were Roman Catholics from western Ulster, who mostly settled in west Belfast. Before this, Belfast had been mostly Protestant.

In 1784, the first Roman Catholic church in Belfast, St. Mary's, was built with money collected from both Presbyterian and Church of Ireland groups, and Protestant businessmen. At its opening, the mostly Presbyterian 1st Belfast Volunteer Company even gave the parish priest a guard of honour. At that time, there were only about 400 Roman Catholics in Belfast. By 1866, this number had grown to about 45,000.

In 1862, George Hamilton Chichester, 3rd Marquess of Donegall built a new castle, Belfast Castle, on the slopes of Cavehill. It was finished in 1870.

Belfast officially became a city in 1888, given its status by Queen Victoria. By 1901, Belfast was the largest city in Ireland. To show its importance, the grand Belfast City Hall was built and finished in 1906. Many Catholics had moved to the city since 1840, settling in areas like the "Pound Loney" in west Belfast. West Belfast is still the main area for the city's Catholic population, while east Belfast is mostly Protestant. Other Catholic areas include parts of north Belfast and the Markets area.

Living conditions for many working-class people were often very poor, with crowded and unhealthy homes. The city suffered from several cholera outbreaks in the mid-1800s. Conditions improved after a big program to clear slums in the early 1900s.

In 1907, Belfast saw a difficult strike by dock workers, organized by Jim Larkin. About 10,000 workers went on strike, and even some police officers refused to break up the protests. The British Army had to be called in to restore order. This strike was unusual because it brought together workers from different religious backgrounds.

Partition and Conflict (1912–1922)

In 1912, a new law called the Third Home Rule Bill was proposed. It would have given Ireland some self-government. However, Unionists, who wanted to stay part of the United Kingdom, formed a group called the Ulster Volunteers to resist this, even with force if needed. This political crisis increased tensions in Belfast, and riots broke out in July 1912.

Later, it was suggested that Ireland should be divided, or "partitioned." Unionists wanted the six northeastern counties of Ireland (where Protestants were the majority in four of them) to remain part of the UK. Home Rule and partition were agreed to in principle by 1914 but were put on hold until after World War I.

After World War I and the Easter Rising of 1916, the questions of Irish independence and partition became very important again. The Sinn Féin party, which wanted full independence, won most seats in Ireland, but not in Ulster. In Belfast, people continued to vote for the Irish Parliamentary Party (Nationalists) and the Unionist Party. A guerrilla war then started between the security forces and the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, Ireland was divided. Northern Ireland, with its six mostly Protestant counties, became part of the United Kingdom, and the rest of the country became the Catholic-dominated Irish Free State. James Craig became Northern Ireland's first Prime Minister.

The time just before and after partition saw a lot of conflict in Belfast. Some areas became much more dominated by one religious group. While this happened at the same time as the Irish War of Independence, the conflict in Belfast was different. In the rest of Ireland, the war was mainly between the IRA and British forces. But in Belfast, about 90% of the 465 deaths were civilians, as the violence often involved attacks between Catholic and Protestant groups.

The conflict in Belfast started in July 1920. Rioting broke out in the shipyards and spread to neighborhoods. This violence was partly a reaction to the IRA killing a police officer in Cork and partly due to competition for jobs because of high unemployment. Loyalists marched on the Harland and Wolff shipyards and forced over 7,000 Catholic and some left-wing Protestant workers out of their jobs. About 20 people died in three days of rioting. Both Catholics and Protestants were also forced from their homes. The killing of a police detective in nearby Lisburn in August caused another round of clashes, killing 33 people in 10 days. This violence led to the return of the Ulster Volunteer Force, a unionist group first formed in 1912. Cycles of violence continued until the summer of 1922.

In response to this violence, people in the south of Ireland stopped buying goods made in Belfast. In Northern Ireland, a new police force, the Ulster Special Constabulary, was created to help control the unrest.

The year 1921 saw three major outbreaks of violence in Belfast. Just before a ceasefire in the Irish War of Independence on July 11, Belfast experienced a day of violence known as 'Belfast's Bloody Sunday'. An IRA attack on a police truck led to fierce fighting in west Belfast, where 16 civilians died and many houses were destroyed. Gun battles happened all day along the dividing line between the Falls and Shankill Road areas. More violence followed in August and November, with many more deaths.

The violence was worst in the first half of 1922, after the Anglo-Irish Treaty confirmed the partition of Ireland. Michael Collins, the leader of the Irish Free State, sent weapons to the northern IRA to help defend the Catholic population and try to make Northern Ireland unstable. Many people were killed in Belfast in February, March, and April 1922. IRA actions, like killing policemen, led to attacks on the Roman Catholic population by loyalists, sometimes secretly helped by state forces.

In May 1922, the IRA killed a unionist politician, William J. Twaddell. After this, 350 IRA members were arrested in Belfast, weakening their group. However, attacks on civilians continued into June 1922. Seventy-five people were killed in May, and another 30 in June. Thousands of Catholics fled the violence and sought safety in Glasgow and Dublin. After this crisis, the violence quickly decreased. Only a few people died in July and August, and the last conflict-related killing happened in October 1922.

Two main reasons led to the quick end of the conflict. First, the IRA became much weaker because the Northern government started holding people without trial. Second, the Irish Civil War broke out in the south, which made the IRA focus its attention away from the North.

Historian Robert Lynch estimates that 465 people died in Belfast during the 1920–22 conflict. Another 1,091 were injured. Of those who died, 159 were Protestant civilians, 258 were Catholic civilians, 35 were from the Crown forces, and 12 were IRA members.

The Great Depression and World War II

As the largest city in Ulster, Belfast became the capital of Northern Ireland. A large parliament building was built at Stormont in 1932. The government of Northern Ireland was mostly led by upper and middle-class unionists. Because of this, conditions in the poorer parts of Belfast remained difficult. Many houses were damp, overcrowded, and lacked basic things like hot water and indoor toilets until the 1970s.

Like many cities around the world, Belfast suffered greatly during the Great Depression in the 1930s. These economic problems partly led to more sectarian rioting in the city. However, the most significant unrest of that time, the Outdoor Relief Riots of 1932, was special because it brought people from different religious backgrounds together to protest.

During World War II, Belfast was one of the major cities in the United Kingdom that was bombed by German forces. The British government thought Northern Ireland would be safe from German bombs because it was far away. So, very little was done to prepare Belfast for air raids. Few bomb shelters were built, and the city's anti-aircraft guns were sent to England.

The Belfast Blitz happened on Easter Tuesday, April 15, 1941. Two hundred German Luftwaffe bombers attacked the city, hitting working-class areas around the shipyards and north Belfast. About one thousand people died, and many more were injured. More than half of Belfast's homes (52%) were destroyed. Outside London, this was the greatest loss of life in a single raid during the war. About 100,000 of the 415,000 people living in Belfast became homeless. Belfast was targeted because it had many important shipbuilding and aerospace industries. Ironically, during this same period, the local economy got better because the war created a huge demand for the products from these industries.

The Troubles

The years after World War II were fairly calm in Belfast. However, tensions between different communities and anger among the Catholic population about widespread unfairness grew beneath the surface. The city exploded into violence in August 1969 when sectarian rioting broke out. Many people felt the police were unfair, and the IRA did not protect Catholic neighborhoods. This was one of the main reasons for the formation of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), which then started an armed campaign against Northern Ireland.

The violence got worse in the early 1970s, with different armed groups forming on both sides. Bombings, killings, and street violence were a constant part of life throughout The Troubles. In 1972, the PIRA set off twenty-two bombs in a small area of the city center on a day known as "Bloody Friday", killing nine people. Loyalist groups, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA), responded by killing Catholics at random from around August 1972 onwards. A particularly well-known group, based on the Shankill Road in the mid-1970s, was called the Shankill Butchers.

The British Army, first sent in 1969 to restore order, became a common sight in Belfast. Large fortified army bases were built, mostly in nationalist west Belfast. At first, the Army was welcomed by the nationalist community, but this changed after incidents like the Falls Curfew in July 1970, when the Army fought a three-day gun battle with the Official IRA in the Falls Road area, resulting in four deaths. Major confrontations continued between the Army and Republican groups throughout the 1970s.

In the early 1970s, many people were forced to move from their homes. Families, mostly Catholic but also some Protestant, living in areas dominated by the other community were scared away. The general decline in manufacturing industries in Europe in the early 1980s, made worse by the political violence, severely damaged Belfast's economy. As recently as 1971, the city and surrounding area had a large Protestant majority, but by 2011, the population was almost evenly balanced. This change is due to higher Catholic birth rates and increasing prosperity, along with Protestants moving away.

In 1981, Bobby Sands, from Greater Belfast, was the first of ten Republican prisoners to die on hunger strike to gain political status. This event caused major riots in nationalist areas of the city. In the 1980s, some of the most famous incidents happened within a week in 1988. First, a Republican funeral was attacked by loyalist Michael Stone (see Milltown Cemetery attack). Then, the following week, at the funerals of Stone's victims, two off-duty soldiers were killed in what became known as the "corporals killings".

In the early 1990s, loyalist and republican armed groups in the city increased their killings of each other and of civilians they considered "enemies." This cycle of violence continued right up to the PIRA ceasefire in August 1994 and the Combined Loyalist Military Command ceasefire six weeks later. The most terrible single attack of this period happened in October 1993, when the PIRA bombed a fish shop on the Shankill Road, trying to kill the UDA leadership. Instead, the Shankill Road bombing killed nine Protestant shoppers as well as one of the bombers.

Even though the armed groups stopped fighting in 1994, the city still shows the effects of the conflict between the two communities. In total, almost 1,500 people have been killed in political violence in Belfast from 1969 until today.

In 1997, unionists lost control of Belfast City Council for the first time ever. The Alliance Party of Northern Ireland gained the power to decide between nationalists and unionists. This continued in the council elections of 2001 and 2005. Since then, Belfast has had two Catholic mayors, one from the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and one from Sinn Féin.

Recent History and Redevelopment

The city has seen a lot of rebuilding and investment since the Good Friday Agreement. The creation of the Laganside Corporation in 1989 marked the beginning of the renewal of the River Lagan and its surrounding areas. Other areas that have been transformed include the Cathedral Quarter and the Victoria Square area. However, communities still remain separated, with occasional small-scale street violence in certain areas and the building of new Peace Lines.

Belfast experienced the worst of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. However, since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, there has been major redevelopment in the city. This includes projects like Victoria Square, the Titanic Quarter, and Laganside, as well as the Odyssey complex and the famous Waterfront Hall.

Images for kids

-

A portrait of Wolfe Tone.