History of the Dunedin urban area facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dunedin City of Literature |

|

|---|---|

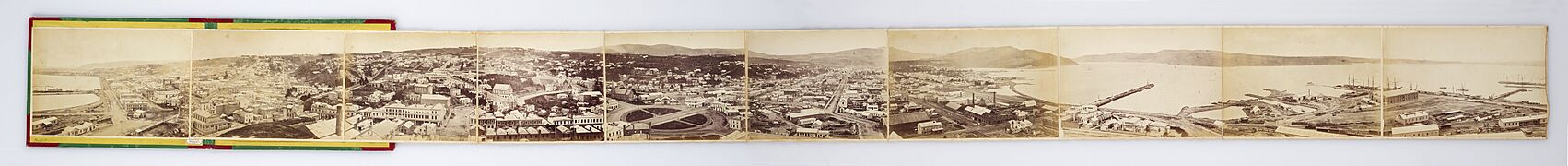

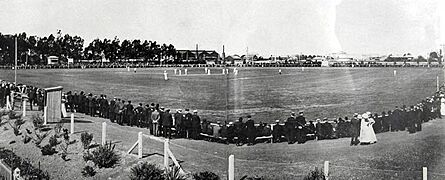

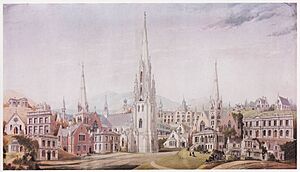

George O'Brien aspirational drawing of Dunedin from the 1860s, First Church had not yet been built and many other depicted buildings never were.

|

|

| Founder | William Cargill |

| Built | 1848 |

Dunedin, a city in New Zealand, has always been a busy place. It connects the inland area of Otago with the rest of the world. While Dunedin's official city limits are quite large, this article focuses on the history of the main urban area. We'll only mention nearby places like Mosgiel or the Otago Peninsula when they help explain Dunedin's story.

Scientists have found proof that Māori first lived in the Dunedin area around 1280 to 1320. They lived along the southern coast and mostly ate seals and moa (a large, now extinct bird). When there were fewer moa and seals, the population went down. In other parts of New Zealand, Māori culture changed to include more gardening, leading to fortified villages called pā. But this new way of life didn't fully reach the colder southern South Island. In central Dunedin, there were two Māori settlements called Ōtepoti and Puketai.

Europeans first arrived in the 1790s. They were sealers and then whalers, working mostly in the lower harbour near Otakou. By 1826, Ōtepoti and Puketai were no longer lived in. This was because many Māori died from diseases like measles. Also, the Musket Wars caused people to move, and new jobs with Europeans changed where people lived.

In 1848, the Free Church of Scotland sent two ships to start a new colony called Dunedin. This was at the top of the Otago Harbour. In 1861, gold was found inland from Dunedin. This led to a huge gold rush, and Dunedin quickly became New Zealand's main industrial and business hub. The University of Otago, New Zealand's oldest university, was started in Dunedin in 1869 because of the gold rush. Later, in the 1880s, exporting frozen meat also helped Dunedin grow. In the 1900s, more people and businesses moved to the North Island. Dunedin then focused on its culture, history, and amazing wildlife on the Otago Peninsula.

Contents

Early Life in the Upper Harbour (1300–1848)

Māori people used the upper harbour area for almost 500 years before Europeans arrived. Not much direct evidence remains from this time. Dunedin's central city is built on a ridge of land between the Toitu Stream and the Water of Leith. The mouths of these rivers were likely used for waka (boats) when people moved between the Otago Peninsula and inland Otago.

For the first 150 years after people settled in New Zealand, the population was very small. The southern South Island was a busy place because of its many seals. After 1500, the area around Dunedin became less populated compared to the North Island. This was because kumara (sweet potato) couldn't grow well in Dunedin's colder climate. Local Māori moved with the seasons to find food. Different tribes and family groups had rights to different resources across Otago at different times. Villages had wharerau (semi-permanent houses) that could be left and easily fixed when groups returned.

Māori stories tell of Rākaihautū shaping the land and of ancient peoples like Kahui Tipua and Te Rapuwai. Later came the Waitaha, then Kāti Mamoe in the late 1500s, and Kāi Tahu from the mid-1600s. These groups didn't completely replace each other. Instead, the main group changed, but people still had family connections to earlier groups. Important people like Taoka and Te Wera are linked to events at places like Huriawa and Ōtepoti. Their descendants are known today. Te Rakiihia, another important person, died and was buried in central Dunedin around 1785.

First Meetings: Māori and Europeans (Early 1800s)

Captain James Cook sailed near the Otago Peninsula in 1770. He named Cape Saunders and Saddle Hill. He drew maps of the area and reported seeing penguins and seals. This brought sealers to the area in the early 1800s. A conflict between sealers and Māori, which started in 1810, lasted until 1823. Once peace returned, Otago Harbour became a busy international whaling port. A sealer named John Boultbee wrote in the 1820s that the Māori settlements around Otago Harbour were the oldest and largest in the south.

The economy quickly changed from a community-based system to one focused on individuals and businesses. Māori quickly started using the pound as money. Europeans relied on Māori for food until the late 1840s. This led to a specialized economy. The introduction of potatoes and pigs also meant Māori on the Otago Peninsula didn't need to move seasonally for food anymore. Sealing and whaling were the main jobs in Otago Harbour until Dunedin was founded. In the mid-1830s, Māori suffered from new illnesses like measles. In the early 1840s, early sheep farmers grazed their sheep in the area that would become central Dunedin.

The Founding of Dunedin (1848)

The upper harbour didn't have a deep-water port. So, Port Chalmers and Otakou, both in the lower harbour, were first suggested for the new colony. But the Otago Peninsula didn't have much flat land and was close to Māori settlements. So, the upper harbour was chosen for Dunedin. The Free Church of Scotland, through a group called the Otago Association, founded Dunedin in 1848. It was meant to be the main town for their Scottish settlement. The best 120,000 acres of land were divided into small city plots, larger suburban plots, and even larger rural plots. There were 2400 properties in total.

The name Dunedin comes from Dùn Èideann, the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, Scotland's capital. Charles Kettle, the city's surveyor, was told to make Dunedin look like Edinburgh. He created a grand and unique design. Builders found it hard to build his bold vision on the challenging landscape, and sometimes they failed. Captain William Cargill, a war veteran, was the leader of the settlement. The Reverend Thomas Burns, a nephew of the famous poet Robbie Burns, was the spiritual leader.

When Dunedin was founded, the new colony still relied on Māori for food. Settlers began clearing land for farming. At first, harvests were unpredictable, but generally better than in Britain. Once enough food was grown, grain was sent to Australia. Some settlers also started working in the trades they knew from before they moved.

Before Europeans arrived, much of The Flat area was wet and marshy. Early settlers built homes on the hillsides at Caversham and St. Clair. In 1849, William Henry Valpy, said to be New Zealand's richest man, arrived at St Clair. He built the first permanent road in the area, connecting central Dunedin to his St. Clair farm. This road ran along the edge of what is now South Dunedin.

In 1852, when New Zealand was divided into provinces, Dunedin became the capital of the Otago Province. This province covered all of New Zealand south of the Waitaki. It was the only one of New Zealand's first six provinces to have a Māori name. There were often disagreements between the 'Old Identity' (the Scottish, Presbyterian majority) and the 'Little Enemy' (the English, Anglican minority). The Dunedin City Council and the Caversham Borough Council often argued. Caversham, now a suburb of Dunedin, was once a busy industrial town founded mostly by English settlers. The town quickly became known for its mud. From 1848 to 1850, branches were laid on the main street to make travel easier. In 1846, a law was passed to create a police force.

The Gold Rush Era (1861)

Before 1861, Dunedin was a small town with only two or three thousand people. But in 1861, gold was found at Gabriel's Gully. This caused a huge number of people to rush to Dunedin. By 1865, Dunedin had the fastest growing population in New Zealand. Many new arrivals were Irish, but also Italians, French, Germans, Jews, and Chinese. The earlier Scottish settlers called them 'the New Iniquity'. This reduced the strong influence of Scottish immigrants and Presbyterianism in Dunedin. In 1865, the Catholic church became very active, and the Jewish community built a synagogue.

During the gold rush, some people became very rich and built grand houses. However, slums also grew in the inner city. Many of Dunedin's first housing areas didn't have proper sanitation. Even the mayor, John Hyde Harris, was warned and fined in 1867 for the poor quality of his housing developments. Diseases like typhoid and cholera were common because of bad drainage and sanitation. Immigrants who received help to come to New Zealand had to have their housing guaranteed for 48 hours. Many stayed in the Caversham immigration barracks, built in 1872. The gold rushes of the 1860s made it hard for the police to keep order.

What Money Could Build

The 1860s and 1870s, during and after the Gold Rush, were a time of great wealth for Dunedin. Many important organizations and businesses were started. The Otago Daily Times, Dunedin's daily newspaper, which is still printed today, opened in 1861. It was founded by William Henry Cutten and Julius Vogel and strongly supported an independent Otago. The University of Otago opened in 1871. It first taught Classics, English, Mathematics, and Science, and Moral Philosophy. The university quickly added new subjects like mining (1872), Law (1873), and medicine (1875).

With lots of money, good building stones, and Scotland's leading architects, many grand and beautiful buildings were built. This was unusual for such a new colony far from Europe. R.A. Lawson's First Church of Otago and Knox Church are great examples. Maxwell Bury's clock tower complex for the University and F.W. Petre's St Joseph's Roman Catholic Cathedral also began during this time. In the city center, the branches used to hold back mud on the streets were replaced with limestone blocks. A sewerage system started being built in 1863 and was finished in 1908. Mornington became home to New Zealand's first golf course in 1872, showing the city's Scottish heritage. The sewage was sent into Dunedin Harbour, which was not popular. Gas lighting was put on Dunedin Streets in 1863.

In 1865, the New Zealand exhibition was held in Dunedin. It showed off the city and Otago's success. The exhibition displayed items from Western Europe and the South Pacific. It was hoped that the exhibition would help Dunedin stay important even after the gold rush slowed down. The main building of the exhibition later became Dunedin's hospital. It was taken down in 1930 to make way for new buildings.

As the city grew quickly during the Otago Gold Rush of the 1860s, settlements expanded, especially around South Dunedin. Chinese settlers were important early residents in the St Clair area. They worked hard to drain the swampy land near the beach and turn it into market gardens. Much of the young city's vegetables came from Chinese gardens near Macandrew Road, Forbury. There were also gardens in Andersons Bay and Tainui. In the late 1800s, a railway and ferry service connected this area to central Dunedin, but they are no longer used. The ferry ran only in the 1890s, and the railway from 1877 until the early 1900s. The railway was meant to go along the peninsula to Portobello, but it only reached Andersons Bay.

Changing the City's Shape

The money and people coming into Dunedin during this time led to big changes in the natural environment around the upper harbour. By the early 1870s, Dunedin looked like a modern city. The main street plan, with a central octagon and long north-south roads, was created by removing Bell Hill in the 1860s. Before 1858, the town was split in two until a path was blasted between Princes Street and the Octagon through the Nga-Moana-e-rua ridge. The dirt from this work was used to fill in the muddy areas, starting with the Queens Gardens. The 1860s also saw the opening of the Forbury quarry to provide building materials for the city. More land was reclaimed from the harbour, which cut off the Māori trading station on the waterfront.

Dunedin's first railway, the Port Chalmers Branch, opened on January 1, 1873. It was the first railway in New Zealand to use the new narrow gauge (1.067 meters). The Main South Line, connecting Dunedin with Christchurch and Invercargill, opened on January 22, 1879. All these railways needed huge earthworks along half the length of the harbour.

The Town Belt, one of the world's oldest green belts, was planned in Scotland when the Otago settlement began in 1848. Residential areas outside this belt became separate towns and joined Dunedin much later. The Botanic Garden, New Zealand's oldest, was started in 1863 near the Water of Leith. This area is now part of the University of Otago. After a big flood in 1868, the gardens moved to their current spot in 1869. The old site's name is still remembered in the name Tanna or Tani Hill, a small steep hill near the university's registry building.

Ross Creek dam was built between 1865 and 1867 to provide drinking water for the city. The lower parts of the Leith River are now in concrete channels. These, and the small dams in the Leith, were built to stop floods like the one in March 1929 from damaging Dunedin North. An earlier big flood happened in 1868. The Leith River used to wind through what is now the city center, flowing into the upper harbour where Cumberland and Stuart Streets meet. The Toitu Stream (now mostly built over) used to run from Mornington down Serpentine Avenue and Maclaggan Street, then south to the harbour. The memory of this stream is kept alive by the angle High Street crosses Princes Street and the name of the Toitū Otago Settlers Museum.

Dunedin's Growth and Challenges (1873-Early 1900s)

After ten years of gold rushes, the economy slowed down. This happened during a time called the Long Depression. However, Julius Vogel's plan to bring more immigrants and develop the country brought thousands more people, especially to Dunedin and Otago. Then, a recession hit in the 1880s. In the early 1880s, the frozen meat industry began, with the first shipment leaving from Port Chalmers. This started a major national industry. In the mid-1890s, the gold dredging boom began. By the early 1900s, Dunedin was doing very well again. Otago Girls' High School (1871) is believed to be the oldest state high school for girls in the Southern Hemisphere. The first Catholic school was established in 1863. In 1893, Bell Tea started making tea in Dunedin.

The New Zealand South Seas exhibition in 1889 was a chance for Dunedin, then New Zealand's leading city, to show off its success.

Between 1881 and 1957, Dunedin had cable trams. It was one of the first and last cities in the world to use such a system. Carisbrook became a sports ground in the 1870s and hosted its first international cricket game in 1883.

Soon after the first electric telegraph line connected Christchurch and Lyttleton in 1862, another network was built between Dunedin and Port Chalmers. The first phone call in New Zealand was made by Charles A. Henry between Dunedin and Milton using a homemade device. The first telephone office opened at Port Chalmers in 1879 to send shipping information to Dunedin. During the 1900s, influence and activity moved north to other cities in New Zealand.

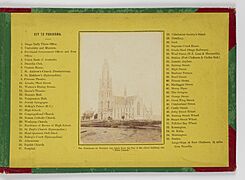

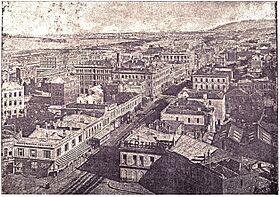

City Centre in 1874

Workers from Taranaki

When a Māori community in Parihaka in Taranaki was disrupted, many people were brought to Dunedin. This happened mainly from 1869-1872 and again from 1879-1881. During this time, these workers helped build many projects around Dunedin and on the Otago Peninsula. This work is linked to a series of tunnels in the Anderson's Bay area.

Women's Rights and Social Change

From the 1890s, Assyrians, who were religious refugees from what is now Lebanon, started to arrive. They often lived in the crowded inner-city areas, many of which were also home to Chinese immigrants. John A. Lee, who later became a well-known Labour politician, grew up in these conditions. His novels showed the country how difficult these living situations were. In 1880, half of the female workforce worked as domestic servants, and their pay was low. As new jobs became available and wages rose, fewer domestic servants were hired. The desire for social improvement and women's equality led to the suffrage movement, which fought for women's right to vote.

About one-third of Dunedin women signed the 1893 Women's Suffrage Petition, which was a higher percentage than any other city. New Zealand's first women's trade union (for Tailoresses) was created in Dunedin in 1889. From the late 1880s, middle-class reformers and worker activists looked into poor working conditions in Dunedin. In the 1880s, workers' groups demanded that Chinese immigrants be excluded because they were seen as working for low wages. In August 1890, the Maritime Council went on strike to support Australian maritime union workers. Difficult economic times led to the 'anti-sweating' movement, led by a Presbyterian Minister, Rutherford Waddell, and the Otago Daily Times newspaper. This movement helped create the New Zealand Labour Party. Henry Fish, the Member of Parliament for South Dunedin, opposed women's right to vote from 1890–1893. He paid people to collect signatures against women's suffrage, but he lost trust when some signatures were found to be fake.

Facing Challenges (Early 1900s)

Compared to the rest of New Zealand, Dunedin was growing slower. However, wealthy merchants like Edward Theomin built grand homes like Olveston. The Dunedin Railway Station, completed in 1906, was also a very fancy building. Reed Publishing was founded in Dunedin in 1907. New Zealand's first radio was built in 1902 by J.L. Passmore, a Dunedin teenager, who later managed a 10 km broadcast. Dunedin's Waipori hydroelectric plant started making electricity in 1907. In 1948, it became the first remote-controlled power station in the Southern Hemisphere. The first public restrooms in Dunedin were built in 1927. More companies and institutions were founded in these years, like the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in 1884, the Otago Settlers Museum in 1898, and the Hocken Collections in 1910. These were all the first of their kind in New Zealand. But Dunedin was no longer the biggest city.

Otago and Dunedin were determined to show their importance to the country. They sent more people to the First World War than other New Zealand areas, and they had more losses (1831 men killed). The Anglican Cathedral, St. Paul's, started in 1915 and was officially opened in 1919. It was the last great Gothic Revival building and is still not fully finished. To show its strength, Dunedin held the 1925 New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition at Logan Park. 3.3 million people visited, more than any other New Zealand exhibition before or since. The money earned from the tramways paid for a new town hall, which is still New Zealand's largest. But the city's population growth continued to slow down.

The first car owned by someone in Dunedin was a steam-powered one in 1901. A delivery van arrived in 1904. Horses were mostly replaced by cars by the 1930s. In 1913, after a public vote, the road to Portobello was opened to cars. It had been closed before due to safety worries.

In January 1907, the sewage pipe that went into the harbour was improved to release sewage at different tide levels. The Musselburgh pumping station was set up in 1908, and a pump was installed in 1911 for better suction. The sewage was then moved to Lawyers Head and later extended further off the coast at St Kilda beach.

This was a time of great creativity in art. William Mathew Hodgkins, called the 'father of art in New Zealand', led a lively art scene. From landscape painters to younger impressionistic artists, G.P. Nerli helped start the career of Frances Hodgkins, who became New Zealand's most famous artist living overseas.

During this time, people also started to notice Dunedin's charm, with its old, grand buildings. Writers like E.H. McCormick pointed out its special atmosphere. R.N. Field at the art school inspired young students to try new things. Artists like M.T. (Toss) Woollaston, Doris Lusk, Anne Hamblett, Colin McCahon, and Patrick Hayman formed the first group of modern artists in New Zealand. The Second World War caused these painters to spread out, but not before McCahon met a very young poet, James K. Baxter, in a city studio.

The First World War

Volunteers from Otago and Southland for the First World War gathered and trained at Tahuna Park in 1914. They were then sent as the Otago Infantry Regiment and Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment to Gallipoli and the Western Front. Otago University helped train medical staff as part of the Otago University Medical Corps. They provided or trained most of the New Zealand Army's doctors and dentists. After the war, returning soldiers received support, but they found women doing many jobs that had been theirs before. The Spanish flu also affected Otago around September to November in 1918.

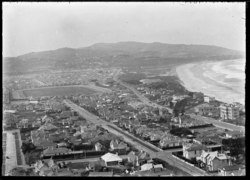

=Images for kids

The Great Flood of 1929

Central Dunedin was flooded badly twice in the 1920s, first in 1923 and again in March 1929. The 1929 flood was Dunedin's worst ever. It was caused by the 1929 New Zealand cyclone, a former tropical cyclone that had already caused damage in the Bay of Plenty. Heavy rain fell from Christchurch to Balclutha, with Dunedin getting most of the storm's impact. Several bridges along the Water of Leith were washed away. Much of the city was flooded, and over 500 houses from North East Valley to Caversham were damaged. After the storm, flood protection work was built along much of the lower Leith River, including dams and concrete channels.

The Great Depression and World War

Dunedin's population dropped slightly during the Great Depression in the 1930s, falling by 3,000 to 82,000 people. In early 1932, there were city protests, which also happened in northern cities later. Despite the city's slow growth, the university continued to expand. This was helped by its unique position in health sciences. New colleges and halls led to the creation of a student area.

Modern Dunedin (1945–Present)

After the war, Dunedin's economy and population grew again. However, Dunedin was now the fourth largest city in New Zealand. The university expanded, but the rest of the city did not grow as much.

This was a time of great cultural activity. The university offered new special positions for writers, composers, and artists. This brought people like James K Baxter, Ralph Hotere, Janet Frame, and Hone Tuwhare to the city. Some stayed, and many spent time there. Good modern buildings appeared, such as the Dental School and Ted McCoy's Otago Boys' High School and Richardson building. These showed how this Dunedin-born designer could combine modern styles with older architecture.

From 1953 to 1975, Dunedin had its first female Member of Parliament, Ethel Emma McMillan. She was also the first woman elected to the Dunedin City Council in 1950.

An urban marae (a Māori meeting place) had been suggested in Dunedin since the 1960s. But it wasn't until 1980 that the Arai Te Uru Marae opened. This made it one of the first urban marae in New Zealand. A fire, started on purpose, destroyed the buildings in 1997. They were rebuilt and reopened in 2003. The marae also provided housing and help for Bhutanese refugees who were displaced by the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes.

In 1969, four regional TV stations started. In 1980, Dunedin and Wellington became one channel, and Auckland and Christchurch became another. Later, they all joined into one system.

Between 1976 and 1981, the city's population actually decreased. This led to a proposal to build an aluminum smelter at Aramoana as part of Sir Robert Muldoon's 'think big' projects. The economic benefits were questioned by Otago Professor Paul Van Moeseke, and the government eventually backed off. But the city became strongly divided over the issue.

In 1974, Dunedin was hit by a magnitude 4.9 earthquake. It caused significant damage to old buildings and many chimneys across the city. In 1979, the Abbotsford landslip happened, destroying half of the suburb. Luckily, no one died.

In the 1980s, Dunedin became known for its lively popular music scene, called the "Dunedin sound". Local bands like The Chills, Straitjacket Fits, The Clean, and The Verlaines became popular in New Zealand and around the world.

In 1972, 1037 newborn babies were chosen for the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (also known as the Dunedin Longitudinal Study). This study has continued to follow these people into adulthood. It gives important information about Dunedin, and New Zealand culture and health in general.

Building a Modern City

The main roads through the city changed to a one-way system in 1968. The first trolley bus started running in 1950, going to Opōho. By the 1960s, Dunedin had 76 trolley buses, which replaced trams. The oil crisis of the late 1970s made them popular again. But by 1983, all electric buses were replaced by diesel ones. Communications changed slowly. Cell phones arrived in 1987, and texting was allowed in 1998. The first computer in Dunedin arrived in 1963 for the Cadbury Fry Hudson manufacturing company.

The Green Island landfill opened in 1981. Fluoride started to be added to Dunedin's drinking water in 1966, and it's now used in 85% of homes. Storm water was separated from sewage in the 1980s.

Dunedin's Reinvention

The population decline stopped, and by 1990, Dunedin had reinvented itself as the 'heritage city'. Its main streets were renovated in Victorian style, and R.A Lawson's Municipal Chambers in the Octagon were restored. The university's growth sped up. North Dunedin became New Zealand's largest and most lively student residential area. In 1989, local government changes created the much larger Dunedin city we know today. It was New Zealand's largest city by area until the creation of Auckland Council in 2010. The city continued to improve itself, moving the Dunedin Public Art Gallery to the Octagon in 1996. It also bought and restored the Railway Station, built a new stadium, and recently completed a large development of the Otago Settlers Museum. New cycle lanes are being built throughout the city and along the western side of the harbour. The Ngai Tahu treaty claim from 1849 was settled in 1998. This created a new economic power in the South Island. The Dunedin Police Station building was built in the 1990s and is used by the New Zealand Police.

In 2014, Dunedin won the "Gigatown" competition. This gave residents a 1Gbit/s internet connection at the normal price. The fiber cable rollout reached 11,615 homes and companies, saving Dunedin an estimated 15 million dollars.

In June 2015, South Dunedin experienced heavy flooding. This happened after a low-pressure weather system brought heavy rain to the coastal Otago region. The flood damage was made worse by the suburb's high water table and a breakdown at the Portobello pumping station. 1,200 homes and businesses were damaged, with total flood damage reaching $138,000,000.

Vanished Dunedin

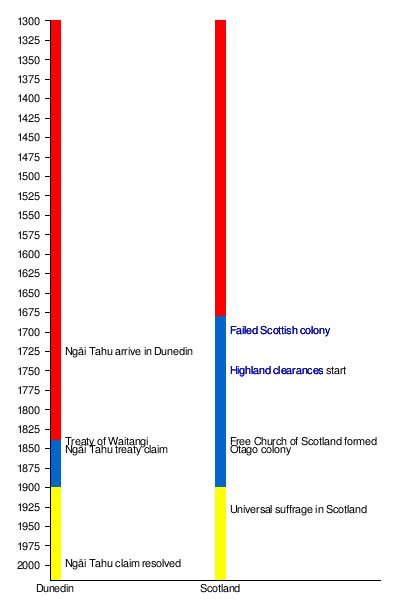

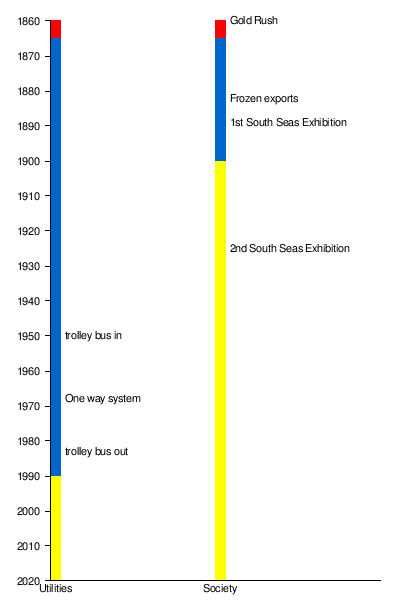

Timelines

See also