History of the Otago Region facts for kids

Otago is a special region in New Zealand. It's quite far away from other big cities and countries. This has shaped its history a lot.

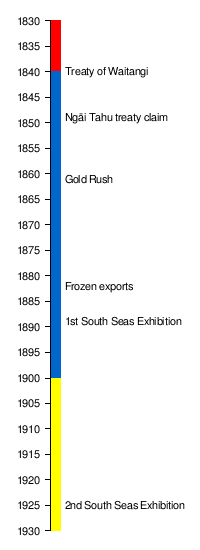

People first came to Otago around the year 1300. These were the Māori, who arrived in New Zealand from Polynesia. They learned to live in this new environment over 500 years. Then, around 1800, the first European seal hunters and whalers arrived. The city of Dunedin was founded in 1848.

New Zealand's nature developed almost alone for 85 million years. When people first arrived, there were almost no land mammals. This meant the animals were very easily hurt by new predators. Humans burned forests, hunted animals, and brought in new plants and animals. This happened in two main waves, around 1300 and 1800. The effects lasted for centuries. Later, people started intensive farming and changed rivers and lakes for water and electricity.

Until the late 1800s, most settlements in Otago were on the eastern coast. This area had many resources and a milder climate. Inland Otago was mostly used for seasonal activities and for its minerals. First, Māori dug for pounamu (greenstone). Then, European settlers looked for gold. When railways and refrigerated trade with Britain started, inland Otago became more productive. Cities grew fast on the flatter eastern coast and in the high inland plains. This also brought big social changes to Otago's people.

Otago's borders have changed over time. The Waitaki River in the north has often been a natural boundary. Ngāi Tahu is the main Māori tribe in the region. They have three sub-tribes in Otago today, and their traditional lands are larger than the current region. Today, Otago is divided into several districts: Central Otago, Clutha, Queenstown-Lakes, and Waitaki (partly in Canterbury). The city of Dunedin has half of Otago's population. The historical Otago Province and the older Murihiku region sometimes included Southland plains, Stewart Island, and Fiordland.

Contents

Early Settlements & Māori Life (1300–1840)

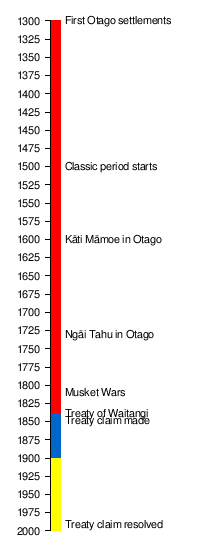

First Māori Arrivals (1300–1500)

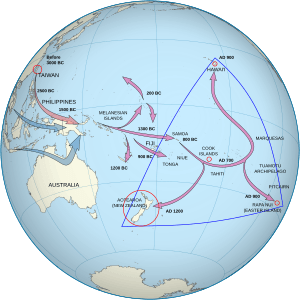

We don't know the exact date when the first people arrived in Otago. Māori are from Polynesian seafarers. They traveled from Asia to the Pacific islands. Stories say they sailed to New Zealand from a place called Hawaiki. They left their home because of too many people and not enough food.

Māori settled New Zealand between 1280 and 1320. They quickly learned to hunt moa birds and seals. They settled across both the North and South Islands very fast. Around 1400, changes in plant life in Otago suggest Māori might have started fires.

The first areas settled were the northern North Island and the east coast of the South Island. Later, less food led to fewer people in the South Island. In the North Island, growing kumara (sweet potato) helped the population grow. This led to different ways of life. More people in the North Island eventually moved to the South Island from the late 1500s.

Māori stories name the Kahui Tipua as the first people in the South Island. They were seen as supernatural beings. After them came the Te Rapuwai tribe. They left few traces, but their names mark many places in Otago. They lived near Kaitangata Lake and the mouth of the Clutha River.

We know little about the next tribe, the Waitaha. Some believe another tribe, the Katikura, lived in Otago before them. The Waitaha are said to have arrived in the Takitimu canoe. This canoe landed in the Bay of Plenty and sailed down both islands. Settlers were left in good areas.

This voyage was so important that people said, "That happened in the time of Tamatea." The Waitaha lived in the South Island for about 100 years. The southern areas had lots of food like fish, seals, and birds. Forests were full of wekas, tūīs, and pigeons. Lakes had many eels. They also found pounamu (greenstone). So, the South Island became known as Te Wahipounamu. Southern Māori moved with the seasons to find food.

The Waitaha were known for their knowledge of chants (karakia) and navigation. They painted designs in caves. They also named many places in Otago. The Waitaha period was peaceful and had plenty of food. Some say they grew so fast they "covered the land like ants." This might mean they found a land with lots of food and their numbers grew quickly.

However, this good time didn't last. By the late 1300s, New Zealand's climate became cooler. Forests shrank, and the moa population went down. People had to find new ways to catch birds and fish. Large early settlements became less important. Some people moved north where they could grow kūmara.

The Waitaha of Otago are sometimes linked to the moa-hunters. This is because many traces of moa-hunters remain. The Waitaha likely hunted moa until they were gone. Moa remains are often found in inland Otago. This suggests the birds lived there longer or the dry air preserved them. Moa may have retreated to Central Otago, especially near Lake Wakatipu and the Lammerlaw Range.

Māori Changes & Migrations (1500–1788)

In the 1800s, Europeans thought the Waitaha lost their land because they were too generous. They sent food to their friends, the Kāti Māmoe. The Kāti Māmoe then wanted the land for themselves. The Waitaha, not used to war, were defeated. But many inter-marriages happened. This "invasion" supposedly began around 1477 AD. However, there are few records of fighting in Otago during this time. Māori stories don't always agree with this idea. It was more likely a migration with some fighting, not a full invasion.

In the early 1600s, a group of the Ngāti Kahungunu tribe moved into Kāti Māmoe land. But they didn't get past Kaikōura. A Kāti Māmoe chief killed their leader, Manawa.

The arrival of the Ngāi Tahu (or Kāi Tahu) tribe in the late 1600s brought more conflict. Some say they wanted the precious pounamu (greenstone) found only in the South Island. But this reason is questioned. The fighting wasn't always just between Kāti Māmoe and Kāi Tahu. The reasons for the fights didn't always mention greenstone. The Kāti Māmoe were never fully "defeated." People of Kāti Māmoe descent still lived in the region when Europeans arrived. Kāi Tahu were just another Māori group living in the south.

Much of this time's history involves two chiefs, Te Wera of Kāi Tahu and his enemy, Taoka. They were cousins and involved in many bloody events.

Another battle happened in 1750 at Balclutha. The Kāti Māmoe won this one. About 15 years later, at Kaitangata, the Kāi Tahu got their revenge and defeated the Kāti Māmoe. Eventually, the two groups agreed to set up a marker on Popoutunoa hill near Clinton. This marked the border between their lands. The Kāti Māmoe were left alone in the southern part of the island. This agreement also involved marriages between Kāti Māmoe and Kāi Tahu families.

This peace ended in 1775. Te Wera's sons built a fort (pa) between Colac Bay and Orepuki. The Kāti Māmoe destroyed it. But their victory was short. As they went to the Otago Peninsula, the Kāti Māmoe group was ambushed at Hillend. Their enemies killed them. Before the end of the century, more fighting broke out at the Otago Heads, Port Molyneux, and Preservation Inlet. One of the last big battles was near Lake Te Anau. Many Kāti Māmoe were killed. The remaining few "disappeared into the gloomy forests."

Traditionally, Europeans believed the Kāti Māmoe were defeated and scattered. However, modern research shows that Kāti Māmoe family lines continued. They were still present in Otago's main families when Europeans arrived.

European Explorers & Traders (1788–1820)

In the late 1700s, European ships visited southern New Zealand. Captain James Cook sailed by but didn't land in Otago. However, in 1770, Joseph Banks saw a fire on the Otago Peninsula. This was the first indirect contact between Māori and Europeans in Otago. After Sydney Cove was settled in 1788, more ships came. These ships brought the first European women to New Zealand. Some people even lived there for years. The first European house and ship in New Zealand were built then.

These visits were often for hunting seals. The first big sealing boom happened. The Europeans met few Māori in these areas. They gave iron tools as gifts. The sealing business picked up again in 1803. This led to detailed exploration of the southwest coast. Ships also explored the east coast and the subantarctic islands. American ships charted Foveaux Strait in 1804. From 1805 to 1807, there was a sealing boom at the Antipodes Islands. Sydney sealers were working on the Dunedin coast by 1809. They had already traded for pigs and potatoes at Otago Harbour by 1810. This was the year the Sealers' War began, a 13-year conflict between Māori and Europeans.

By 1809, Māori in the Foveaux Strait area were growing potatoes. When Captain Fowler arrived at Otago Harbour, locals already had potatoes. They wanted to trade them for iron. Māori settlements may have changed to trade with the "Tongata Bulla" (people of the boats). In 1810, the Sydney Gazette said Māori in Foveaux Strait were "friendly." They wanted to trade potatoes for iron tools. The Ngāi Tahu around Otago also wanted to trade.

In 1810, an incident at Otago Harbour angered Māori. A group of Māori attacked and killed Robert Brown's party near Moeraki. This was in revenge for an earlier event. These early contacts left some Pākehā (non-Māori) living in the south. James Caddell, an English boy, was captured in 1810. Three Indian sailors also survived. In 1815, William Tucker settled at Whareakeake. He had goats and sheep and a Māori wife. He also traded greenstone hei-tiki.

In 1817, James Kelly's ship, the Sophia, was at Otago Harbour. Local chief Korako didn't take Māori from Whareakeake to get gifts from Tucker. Later, Kelly, Tucker, and others went to Whareakeake. Māori attacked them, killing Tucker and two others. This was due to the earlier slight and bad feelings since 1810. Kelly and the others went back to the Sophia. They found Māori on board, who they thought were going to attack. The Europeans fought them off. Then they destroyed Māori boats and burned "the beautiful city of Otago."

Relations between Māori and Pākehā became worse after 1810. A chief named Te Wahia stole items from a ship. A sealer killed him. This started the Sealers' War. Both sides attacked each other. Māori killed men from the schooner The Brothers and the brig Matilda. The fighting lasted until 1823. Captain Edwardson helped end it. This started a new sealing boom, which both Māori and Pākehā wanted.

Edwardson realized Māori wanted to trade. With help from Caddell, he arranged a truce. The peace brought a short return of trade. Even the "unpredictably ferocious" Otago Harbour Māori changed their behavior for trade. About 15 to 20 Europeans lived on Codfish Island. Many had Māori wives. They followed Māori customs.

The safety of these Europeans depended on the main chief in Murihiku, Te Whakataupuka. He was the son of Honegai, who had fought Europeans. Te Whakataupuka was less aggressive. He was good at dealing with the new arrivals. He moved to Ruapuke Island because it was important for trade. John Boultbee described Te Whakataupuka as very strong and elegant. He protected the Europeans. He would joke with them. But there were limits. Once, a European accidentally hit his head with a potato. The chief's head was sacred (tapu). Te Whakataupuka got angry and threw a log. He then told them to stop before he hurt them. When Te Whakataupuka's son died, Europeans feared the chief would blame them. But he didn't let his warriors seek revenge.

From the 1820s to the 1850s, the chiefs at Otago were Tahatu, Karetai, and Taiaroa. Unlike Te Whakataupuka, they were not known for fighting. There were tensions between them. Karetai was the local chief. But Taiaroa had land on the western side of the harbor. He moved his village closer to Karetai's to join the trade. Trade grew fast. In 1823, there were three villages in the harbor. In 1826, there were five. The Otago Harbour Māori became wealthy. They traded pigs and potatoes for muskets and tools.

The Musket Wars

Ngāti Toa Attacks

In 1829, Te Whakataupuka sold land at Preservation Inlet to Peter Williams. He received 60 muskets, gunpowder, musket balls, cannons, and other goods. This gave southern Māori more weapons. It also helped set up the South Island's first whaling station. The Weller brothers set up another station at Otago Harbour in 1831.

By 1830, the threat of northern tribes invading the South Island grew. Te Rauparaha, chief of the Ngāti Toa, attacked the South Island. He stormed the village (kāinga) of Takapūneke at Akaroa Harbour. He took the chief, Tama-i-hara-nui, hostage. A year later, he attacked Kaiapoi, the main Kāi Tahu center in Canterbury. Taiaroa led a strong force of Otago warriors. They slipped past Te Rauparaha and entered the fort at night. After a long defense, Taiaroa and his men escaped to Otago Harbour. This was now the Kāi Tahu stronghold. They planned a counter-attack.

After Te Rauparaha's first attack, 350 armed warriors from Otago marched north. They were led by Te Whakataupuka and Taiaroa. They caught the Ngāti Toa warriors at Te Koko-o-Kupe / Cloudy Bay. Taiaroa and Tūhawaiki grabbed Te Rauparaha. But he slipped out of his cloak and swam to his canoes. Kāi Tahu claimed victory. Ngāti Toa said they escaped the ambush. The sea fight was not clear, but Te Rauparaha got away. In 1835, Taiaroa and Tūhawaiki led another large group of 400 men. Tūhawaiki became the main chief of Murihiku after Te Whakataupuka died that year. They caused heavy losses to Ngāti Toa. Te Rauparaha's reputation suffered.

Māori fighting made Europeans nervous. Trade became risky. In August 1834, a ship captain reported that Māori at the Weller brothers' whaling station were treating Europeans badly. They talked of killing all Pākehā. They took whatever they wanted. Four whaling captains complained. They said a "powerful tribe" under Taiaroa was at war. This tribe had destroyed whaling property. Their own Māori protectors could not help them.

Then, disease changed everything. In September 1835, measles and influenza spread among the southern Kāi Tahu. Te Whakataupuka died. Many Māori died. One European said a village had nine canoes but only enough men for one. Whalers often blamed disease for the drop in Māori numbers.

But the last tribal war had not happened yet. In 1836, Te Puoho, a relative of Te Rauparaha, tried to get Te Rauparaha to attack Otago. Te Rauparaha refused. Te Puoho then led about 70 warriors down the West Coast. They crossed the mountains through Haast Pass. They were starving. They captured a village at Wānaka. They went through the Cardrona Valley and Crown Range. They crossed the Kawarau River and entered Murihiku. After resting, they followed an old Māori track. They crossed the Mataura River and sacked the village of Tuturau.

However, the south soon knew about the invasion. Te Puoho didn't know that news had reached Tūhawaiki at Ruapuke. Taiaroa was also visiting the island. The two chiefs quickly gathered 70 to 100 men. Whalers took the warriors to the mainland. Local Europeans were scared and ready to flee. The Ngāti Toa slept at Tuturau. The Kāi Tahu surrounded the village. In the morning, Kāi Tahu quickly defeated the invaders. Te Pūoho was killed. Taiaroa saved some of his relatives who had helped him escape Te Rauparaha earlier. At Ruapuke, Bluff, and Otago, Europeans and Kāi Tahu celebrated their victory.

This was the last major Māori war in the South Island. In January 1838, Tūhawaiki and Taiaroa marched to Queen Charlotte Sound. In December 1839, they led another war-party. But Te Rauparaha never faced the southern warriors again. These trips showed that the southerners were no longer afraid of the northerners.

European Settlement & Growth (1840–1900)

The Treaty of Waitangi didn't seem very important in Otago at first. The Crown even said the area was empty. But land sales and European immigration plans made the treaty a key moment in Otago's history.

Land Sales & the Treaty of Waitangi

In the 1830s and 1840s, Māori in Otago and Murihiku sold much of their land. They might have wanted a strong European presence. In 1833, Joseph Weller bought all of Stewart Island and two nearby islands from Te Whakataupuka for £100.

In 1838, Tuhawaiki and four chiefs visited Sydney. They sold huge areas of land. People in Sydney were very excited about buying land in New Zealand. On January 14, 1840, Governor George Gipps said no more land could be sold unless to the Crown. He also said that all past land sales would be checked. A month later, on February 15, 1840, Tuhawaiki and other chiefs signed an agreement. They "sold" the South Island and Stewart Island. This included all seas, harbors, rivers, lakes, and minerals. They only kept parts already sold. They received cash and yearly payments. Tuhawaiki signed for £100 and £50 a year for life. By February 1840, it seemed all land in Otago and the South Island had been sold to hopeful buyers.

These sales were very questionable. Captain William Hobson arrived in New Zealand in January 1840 to get Māori to agree to British rule. He said the Queen would not accept land titles not approved by the Crown. After northern chiefs signed the Treaty, HMS Herald sailed south. On June 9, 1840, Major Thomas Bunbury collected signatures for the Treaty of Waitangi at Ruapuke. Tuhawaiki, dressed in a British army uniform, signed the Treaty without hesitation. Kakoura and Taiaroa also signed. Tuhawaiki even had 20 men in British uniforms as bodyguards.

Scottish Settlement & Growth

The New Zealand Company bought the Otago block from Ngāi Tahu leaders on July 31, 1844. They paid £2,400. This opened the way for many European settlers in Otago. The settlement was planned to be called New Edinburgh. But they used the local name Otago instead. George Rennie and William Cargill, both from Scotland, supported the settlement. The Free Church of Scotland also backed it.

The first settlers arrived on two ships from Scotland in 1848. The John Wickliffe came first. The Philip Laing arrived three weeks later with twice as many passengers. Early immigrants were mostly from Scotland's lowlands. Land in Dunedin was already divided. Settlers drew lots in Scotland to choose their land. About half of the new arrivals were from the Free Church. Of the 12,000 immigrants who came in the 1850s, about 75% were Scottish.

William Cargill (first leader 1853–1860) and Thomas Burns were the leaders. Both were Scottish. But some Englishmen also held important positions. John Turnbull Thomson, an English surveyor, named many places in Otago. Otago's other coastal port, Oamaru, was planned in 1858. Its streets were named after British rivers. Some settlers came as assisted immigrants. A ferry service across the Clutha River was set up at Balclutha in 1857.

The settlement had a mix of strict Free Church values and new colony ways. For example, the Sabbath Ordinance meant no games or work on Sunday. Free primary education was also introduced.

Most farm products were sold to southeast Australia during their gold rush. Sheep farming started, with half a million sheep by 1861. Land was often leased to farmers. Wages were higher than in Scotland. Some farmers moved inland to create large stations near Lake Wakatipu and Wanaka. But Central Otago wasn't fully settled until after the Otago gold rush.

By 1849, Ngāi Tahu felt the Crown had not kept its promises from the Treaty of Waitangi. This included those in Otago. They made a claim against the Crown. The claim said the Crown failed in three main areas: building schools and hospitals, setting aside 10% of the land as reserves, and providing access to food gathering places. Ngāi Tahu took the case to court in 1868. But no decision was made. This was partly because the Crown didn't want to act. The claim remained unsolved for over 100 years. By the end of the century, fewer than 2,000 Ngāi Tahu lived on tribal land.

The Gold Rush Era (1861–1870)

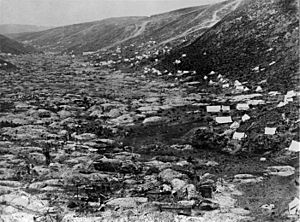

Gold was very valuable to Europeans for trade and jewelry. When it was found in Otago in 1861, near Lawrence, it greatly boosted the economy and immigration. Dunedin quickly became New Zealand's largest city. Transport and towns grew into the inland areas.

In 1862, the gold rush spread across inland Otago to Cromwell and Arrowtown. Queenstown, once a sheep station with a hotel, became a busy town. In 1863, new gold finds were made closer to the coast. 1863 was the peak of the gold rush. About 22,000 people lived in the gold fields. In the 1860s, Otago earned £10 million from gold. It earned only £3.57 million from sheep. Water sluicing extended the life of the diggings. But it also damaged the land. After 1864, no more big gold discoveries attracted people from overseas. In 1865, Dunedin's wealth and the wars in the North Island led Otago to support becoming independent from the North Island. This effort failed.

In 1866, Chinese immigrants came to Otago. Local businesses supported them. They worked in the gold mines. They faced unfair laws and treatment from other immigrants.

When New Zealand provinces were formed in 1853, southern New Zealand was part of Otago Province. Settlers in Murihiku wanted to separate from Otago. They started asking the government in 1857. The province of Southland was created in 1861. But Southland got into debt by the late 1860s. So, it became part of Otago Province again in 1870.

Refrigerated Exports & Inland Development (1870–1900)

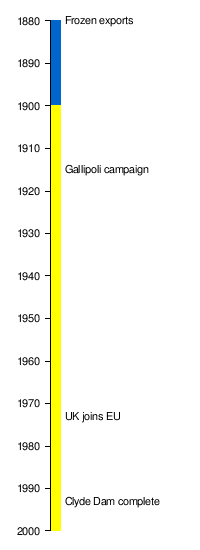

By 1870, one-quarter of New Zealanders lived in Otago because of the gold rush. One-third of New Zealand's exports came from Otago. In 1881, Dunedin was New Zealand's largest city. Many new Irish and English immigrants arrived. This changed the province from being mostly Scottish. The Long Depression was a worldwide economic downturn. It started in 1873 and lasted until 1879 or 1896. In Otago, this came after the gold rush. But by 1882, sheep farming and the frozen-meat industry helped. They could send refrigerated meat to Britain. This helped Otago's economy keep growing.

Wool and lamb were the main exports. But in the 1880s, erosion, rabbits, and sheep diseases caused problems for farmers. The first refrigerated shipment to Britain was in 1882. It left Port Chalmers on the SS Elderslie. This led to meat-freezing factories being built near Dunedin (Burnside) and in Oamaru and Balclutha (Finegand). Large land holdings in North Otago were divided into smaller farms between 1895 and 1909. Hot summers and cold winters were good for growing fruit. Orchards developed in Central Otago from the late 1800s.

To support farming, a railway network was built. It started in Dunedin in 1889. It reached Hyde by 1894, Clyde in 1907, and Cromwell in 1921. Gold mining became less labor-intensive. From the 1880s, quartz mining became possible. Huge dredges continued to work old gold deposits. These dredges inspired the first hydroelectric power station at Bullendale in 1886. This gold boom peaked between 1890 and 1900. But it put many individual gold prospectors out of business.

The 1893 Women's Suffrage Petition was a big effort to get women the right to vote. About one-third of Dunedin women signed it. This was a higher percentage than any other city.

Workers' Rights & Social Change

From the late 1880s, people started looking into bad working conditions in Dunedin and Otago. In 1889, New Zealand's first women's trade union, the Tailoresses, was formed in Dunedin. This happened after a report showed that women in clothing factories were being "sweated" (paid very little for hard work).

Worker groups in the 1880s wanted to stop Chinese workers from coming. They believed Chinese workers accepted very low wages. In August 1890, the Maritime Council went on strike to support Australian workers. Many immigrants liked the environment around Dunedin. But the city didn't have enough services for many workers. Workers protested low wages and high rents. Samuel Shaw, a painter from England, helped the workers. After a meeting and a petition, an eight-hour workday was agreed upon.

Workers who came to Otago expected to leave class differences behind. But by the 1880s, worker disputes created a common identity for them. Unskilled workers had not been organized before. Their problems were usually solved informally. Skilled workers had more freedom and security. They were important in Otago towns in the 1860s and 1870s. By the 1880s, Dunedin was becoming an industrial city. Both skilled and unskilled workers formed unions. The Trades and Labour Council worked to improve working conditions.

In 1887, Samuel Lister started the Otago Workman newspaper. He said it would "fearlessly take up the cause of the industrial classes." Historian Erik Olssen said the paper "played a major role in shaping a sense of working-class identity." On October 28, 1990, many workers in Dunedin supported unions during the Maritime Strike. Even though the strike failed, it showed how quickly an industrial working class had grown.

Between 1900 and 1910, Dunedin faced changes from industrialisation. A rich business group still controlled Otago's economy. Unions and businesses protested what they saw as the government ignoring the region. People felt proud of what they had achieved as Scottish pioneers. Another problem was how local politics affected basic services like drainage and water. There was some unity in solving this. The Trades Council and a socialist group, the Fabian Society, successfully pushed for changes. Engineers and urban planners helped improve fire services, public transport, and local government.

In 1894, Clutha banned alcohol sales. Oamaru followed in 1905, and Bruce in 1922. In 1917, pubs had to close at 6 pm. Otago sent men to fight in the Boer War in South Africa. This was the first of many overseas wars for men from Otago.

The Clutha River had several big floods. The "Hundred year floods" in 1878 and 1978 were the most notable. The 1878 flood was New Zealand's biggest known flood. A bridge at Clydevale was washed away. It hit the Balclutha Road Bridge, destroying it.

Bendix Hallenstein started his retail business in Queenstown in the 1860s. He moved to Dunedin in the early 1880s. By the 1900s, his business was all over New Zealand. The first New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition in 1889–90 was a highlight for Dunedin's economy and culture. Otago's tourism potential was known since the 1870s. The railway from Dunedin to Kingston in the late 1870s helped tourism grow. By the early 1900s, summer tourism around Lake Wakatipu was well established.

Modern Otago: Challenges & Changes (1900-Today)

In the early 1900s, New Zealand began to become more independent. In 1901, New Zealand chose not to join Australia. In 1907, the United Kingdom gave New Zealand "Dominion" status. This meant it was still part of the British Empire but had more control. The high number of deaths in the First World War also played a role. In 1920, New Zealand joined the League of Nations as a sovereign state. Other regions, especially in the North Island, started to grow more important than Otago in population and economy.

Wars & Economic Hardship (1900–1945)

Otago had a slow start to the new century. Then came two world wars and a depression. In 1920, the number of sheep in Otago was the same as in 1880. Rabbits, erosion, and distance from world markets were still problems. Farming quickly expanded into forested areas. But many farms, especially in the Catlins, were not profitable. They returned to forest or scrub.

When the First World War started, the Otago Infantry Regiment was formed. They served at Gallipoli in 1915. Then they moved to the Western Front from 1916 until the war ended. Eight hundred women formed the Otago and Southland's Women's Patriotic Association in 1914. They supported the troops overseas. Four thousand men from Otago died during the war. When the war ended, the Spanish flu struck in late 1918.

By 1923, Dunedin was New Zealand's fourth largest city. The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 changed global trade routes. This led to economic slowdown in Dunedin. To respond, Dunedin held the second New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition in 1925. Dunedin grew slowly during this time. Its population dropped slightly during the Great Depression. It fell by 3,000 to 82,000.

The labor movement in Otago was slower to organize than in other regions. During the Depression of the 1930s, unemployed workers were sent to gold workings in Otago. They got 30 shillings a week and could keep some gold they found. In the 1932 depression, there were riots in Dunedin. Stores and cars were damaged. Food packages were then given to the unemployed.

Post-War Prosperity & Social Change (1945–1973)

After the war, Britain needed food. Better farming methods led to more prosperity in Otago. This caused cities and towns to grow. Oamaru's population grew by 75%. Balclutha's doubled. Alexandra's and Mosgiel's tripled. Dunedin's population quickly returned to its pre-depression level. By 1946, there were 100 rabbit boards. Their job was to control rabbits on farmland.

Large electric power stations were built on the Waitaki (Aviemore 1968) and Clutha (1956–62) rivers. A container terminal was built at Port Chalmers in 1971. However, more recent projects faced protests due to environmental concerns. The save Manapouri campaign from 1959 to 1972 and cost overruns on the Clyde Dam made future large projects harder. These projects did lead to population growth in nearby towns.

In 1960, commercial jet boat rides started in the Queenstown area. A rope tow on Coronet Peak (1947) and hiking huts were built. This made Queenstown and the lakes district a year-round tourism center. In 1967, pubs were allowed to stay open until 10 pm again.

A New Global Role (1973-Today)

Otago sent most of its products to the United Kingdom until the 1970s. This changed when the United Kingdom joined the European Community in 1973. They ended their special trade deals with New Zealand. This, along with oil crises and a new government, caused economic problems in Otago. The Labour government then decided to open up New Zealand's markets. This was to make New Zealand more competitive globally. This led to a shift away from farming. Woolen mills in Kaikorai Valley, Milton, and Mosgiel closed between 1957 and 2000.

Several counties joined together in 1989 to form the Otago Region. This new region was smaller than the 19th-century Otago Province. That older province had included Fiordland and Stewart Island.

Queenstown's main industry became tourism. This includes wine tasting, golf, and adventure sports. Skiing, jet boating, rafting, and bungee jumping became popular. Farming shifted from sheep to dairy. Dairy farming uses more water and power. The old railway was turned into a bike trail for tourists in 2000.

Ngāi Tahu's land claim from the 1840s was recognized in 1991. Talks between the Crown and Ngāi Tahu began that same year. The Waitangi Tribunal said that the Crown bought 34.5 million acres (more than half of New Zealand) from Ngāi Tahu for only £14,750. They left Ngāi Tahu with only 35,757 acres. The Tribunal concluded that the Crown acted unfairly and broke the Treaty of Waitangi many times.

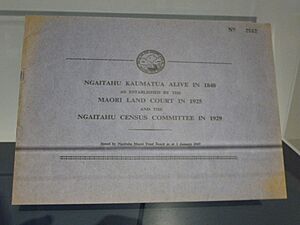

Court battles continued. But the Prime Minister, Jim Bolger, helped. A non-binding agreement was signed in 1996. This was followed by the Deed of Settlement in 1997. The Ngāi Tahu Claim Settlement Act passed in 1998. The Crown agreed to several things. They allowed Ngāi Tahu to express their traditional connection to the environment. They issued an apology. They gave Ngāi Tahu $170 million. They also returned ownership of pounamu. To be a beneficiary of the Ngāi Tahu claim, people must prove they are descended from members alive in 1848. The list of 1848 members (the 'Blue Book') was made in the late 1800s.

Plans for hydro power plants on the Clutha and Waitaki rivers were stopped. However, several wind farms have been built in Otago. The Mahinerangi Wind Farm was built in 2011. A project in the Lammermoor Range was canceled in 2012 due to environmental and legal issues.

See also

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |