History of Paraná facts for kids

The history of Paraná, a state in Brazil, started long before Brazil was "discovered" by Europeans. The first people to live here were three main groups of Native Brazilians: the Tupi-Guaranís, the Kaingangs, and the Xoklengs. Over time, some of the first cities founded in the state were Paranaguá, Curitiba, Castro, Ponta Grossa, Palmeira, Lapa, Guarapuava, and Palmas.

Contents

- Early Explorers and Settlements

- Becoming a Province

- The Era of Cattle Drivers

- Expanding Farming and Ranching

- Province of Paraná is Created

- Changes in Society and Economy

- New Settlements and Immigrants

- Paraná in the Republic

- Farming and Land Issues

- The 1930 Revolution and Changes

- Progress and Challenges

- Stability and Development

- Political Changes

- 21st Century

- See also

Early Explorers and Settlements

Before the Portuguese arrived, in the 1500s, the Paraná region was mostly ignored by Portugal. Other countries, especially Spain, explored it, looking for valuable wood. Spanish explorers brought Jesuit priests who started settlements in western Paraná.

Between 1521 and 1525, an explorer named Aleixo Garcia led a group called a bandeira. They traveled through Paraná, exploring rivers like the Paraná, Paranapanema, Tibagi, and Iguazu. They even reached the Andes mountains. In January 1542, another Spanish explorer, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, followed an old Native American trail called Peabiru. He reached the amazing Iguazu Falls, becoming the first European to describe them in his writings.

Other explorers, like the Germans Hans Staden (in 1549) and Ulrich Schmidl (in 1552), also passed through what is now Paraná. In 1554, a Spanish governor named Domingo Martínez de Irala founded a town called Ontiveros near the Salto das Sete Quedas. Later, another town, Ciudad Real del Guayrá, was founded nearby. In 1576, the Spanish started Vila Rica do Espírito Santo. This area, with its towns and Jesuit "reductions" (settlements for Native Americans), was known as Provincia Real del Guaíra.

In the early 1600s, after gold was found in Paraná, Portuguese-Brazilians from São Vicente began to move into the region. These groups, also called bandeirantes, destroyed most of the Jesuit settlements in 1629. By 1632, Antônio Raposo Tavares destroyed Vila Rica, the last Spanish stronghold.

Settlers made homes on the coast and in the highlands of Paraná. Paranaguá was a popular spot and one of the southernmost Portuguese settlements in America. In 1693, Curitiba became a town and grew into an important center for expanding the territory. Finding gold was hard because they didn't have advanced tools and there weren't enough workers. Gold was found in Paraná before Minas Gerais, but when more gold was discovered in Minas Gerais, people mostly stopped looking for it in Paraná.

In 1820, the western part of Paraná became part of the Portuguese crown and was linked to the Province of São Paulo. It was called Comarca de Curitiba. People then focused on farming and raising cattle. Curitiba grew because it needed to feed and transport miners from Minas Gerais. A new road, the Viamão-Sorocaba road, connected Rio Grande do Sul to São Paulo through Curitiba. This started a new period in Paraná's history: the tropeirismo, or the era of cattle drivers, which lasted through the 1700s and 1800s. Cattle ranches spread, and the cattle rancher became a very important person.

Becoming a Province

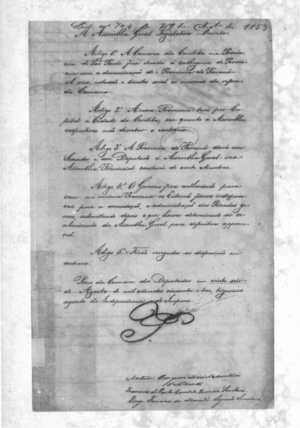

The areas of Paranaguá and Curitiba, which were part of the Captaincy of São Paulo, were officially created on November 19, 1811. Even after Brazil became independent, the region remained under São Paulo's control. On February 6, 1842, Curitiba was made a city. Finally, on August 29, 1853, Emperor Pedro II signed a law creating the Province of Paraná.

There were several reasons for this. One was to punish São Paulo for its part in the Liberal Revolt of 1842. Another was to reward Paraná for supporting the Ragamuffin War. Also, growing yerba mate was becoming very profitable. Curitiba was chosen as the capital, and Zacarias de Góis became the first president of the province.

Because Paraná had a small population, an official program to bring European immigrants started. People from Poland, Germany, and Italy came, helping the state grow and start new businesses. After Brazil became a republic in 1889, more people settled in Paraná, especially in the northern part of the state, which had very fertile "terra roxa" soil. Here, coffee farms and new cities began to appear along the Paranapanema, Cinzas, and Jataí rivers.

The Era of Cattle Drivers

When gold was discovered in Minas Gerais, there was a big demand for horses and cattle. These animals, especially mules, came from the southern missions region. They were transported along the Viamão-Sorocaba road, which opened in 1731. This road was very important for Paraná's history. It connected Curitiba to the cattle trade, moving it away from the coastal trade of Paranaguá. This allowed Curitiba to grow and become the main city of the future province.

This period, known as the "troop cycle," lasted until the 1870s, when railroads started to take over. Many people made money by buying mules in the south and selling them at fairs in Sorocaba. The land was settled by spreading cattle ranches. Wealthy families gained power by owning pastures and using the labor of enslaved Black people and Native Americans. Towns like Lapa, Ponta Grossa, and Castro grew thanks to these cattle routes.

Expanding Farming and Ranching

In the early 1800s, with wars happening in the south, Portugal wanted to settle the lands that belonged to them by the Treaty of Madrid. These lands had been empty since the Jesuit missions were destroyed by the bandeirantes.

To settle the land, control the Native Americans, and open routes to the missions, a military operation reached the fields of Guarapuava in June 1810. These lands were soon given out for farming. Captured Native Americans were given to "wealthy residents," and the region was settled over the next thirty years. Then, the fields of Palmas were taken from the Native Americans in 1839 by two competing private groups. They settled their dispute without fighting. By the mid-1800s, thanks to ranching, the countryside was also settled.

Province of Paraná is Created

On February 19, 1811, the areas of Paranaguá and Curitiba were officially created as part of the Captaincy of São Paulo. Later that year, the city council of Paranaguá asked the prince regent to make their area a new captaincy. Ten years later, a group called the Separatist Conjuration openly asked for independence, but they were not successful.

Even after Brazil became independent, the people of Paraná were still controlled by local military leaders. The provincial government was far away and didn't pay much attention to the region. However, Paraná's political and strategic importance grew over the years. Events like the Ragamuffin War and the liberal rebellions of 1842 showed its importance on a national level.

On May 29, 1843, a proposal to make the Curitiba region a province caused big debates. Deputies from Minas Gerais and São Paulo argued about it. São Paulo's deputies believed the real reason for creating the new province was to punish São Paulo for its role in the 1842 rebellions. At the same time, Paraná's economy was booming. Besides cattle trade, it was exporting native yerba mate to markets in the Plata region and Chile. Promises of independence were made, and the fight in parliament continued. Finally, on August 28, 1853, the project for the province of Paraná was approved, with Curitiba as its temporary capital.

On December 19, 1853, Zacarias de Góis e Vasconcelos, the first president of the province, arrived in Curitiba. He immediately started working to boost the local economy and get money for necessary government actions. He tried to move some workers and money from yerba mate production and trade to other activities, especially farming. However, the most profitable business in the province continued to be selling mules to São Paulo. This business was at its peak in the 1860s and only declined at the end of the century.

During the provincial period, Paraná's government often changed leaders. The president of the province was chosen by the central government, and there were 55 presidents in 36 years. Local political groups, like the liberals led by Jesuíno Marcondes, and conservatives led by Manuel Antônio Guimarães, competed for power.

Changes in Society and Economy

The decline of the mule trade caused problems for Paraná's ranching society. Large family properties could no longer support everyone. Children of farmers moved to cities, São Paulo, and Rio Grande do Sul. Since the early 1800s, Paraná had been receiving immigrants, like people from the Azores, Germany, Switzerland, and France, but in small numbers.

By the mid-1800s, even with about sixty thousand people, Paraná still had huge empty areas. There were only nineteen small settled places, far apart. These included the two main cities, Curitiba and Paranaguá; seven towns like Guaratuba and Lapa; six parishes like Campo Largo and Ponta Grossa; and four chapels. Most of the territory was empty, covered by vast fields, forests, and the Serra do Mar mountains.

At the end of the 1800s, Paraná's economy grew again when railroads were built. This helped the wood industry, connecting the Araucaria forests to ports like Paranaguá and São Paulo. However, this also meant the end of mule transport, causing problems for the old ranching society.

New Settlements and Immigrants

In the second half of the 1800s, the government encouraged new settlements to boost farming and feed the growing population. The imperial and provincial governments worked together to create new farming communities near cities, especially around Curitiba. These communities were made up of people from Poland, Germany, Italy, and smaller groups from Switzerland, France, and England. These immigrants greatly shaped the diverse population of Paraná. In some places, like Castro, people still speak Dutch, and in other areas, you can hear German, Italian, Ukrainian, Polish, and Japanese.

The number of enslaved people in Paraná decreased a lot from the mid-1800s, mainly because they were sold or leased to other provinces. A report from 1867 noted that the tax collected on enslaved people going to São Paulo was almost as much as the tax on animals.

So, bringing in settlers helped solve the problem of not having enough farm workers and food, especially as enslaved labor decreased. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, more than forty new settlements were created in Paraná. Immigrants also helped build railroads and telegraph lines.

Paraná in the Republic

After Brazil became a republic in 1889, Paraná faced several political challenges. The state's constitution was finally approved in April 1892. The state also had a complicated border dispute with Santa Catarina that lasted until the early 1900s. Both states claimed the same lands.

Santa Catarina won its case in the Supreme Court three times, but Paraná blocked the decisions. This disputed area was where the Contestado War was fought. Finally, in 1916, the president of Brazil decided to divide the disputed region, ending the conflict.

Farming and Land Issues

In 1920, Paraná was the 13th most populated state in Brazil. By 1960, it had jumped to fifth place, with over 4.2 million people! This huge growth was due to more births and many people moving from other states to previously empty areas in Paraná. Since the 1920s, people from Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina, often descendants of Germans and Italians, had been settling the land on their own.

Since the late 1800s, farmers from São Paulo and Minas Gerais started growing coffee in the northern part of Paraná, which had rich, fertile "terra roxa" soil. New waves of immigrants also arrived. In 1924, a British lord named Lord Lovat visited Paraná. Three years later, he got permission from the government for a huge amount of land in the north. He then founded Paraná Plantation Ltd., which, along with other companies, planned to settle the area. In the region of the Iguazu and Paraná rivers, companies had long been cutting wood and collecting mate. The city of Londrina became the center of this growth and expanded very quickly.

After the 1930 revolution, many land deals were canceled. The state government and private groups then started organized settlements, focusing on diverse farming and raising small animals.

The 1930 Revolution and Changes

The revolution began in October 1930. Its supporters, with military help, took control of Paraná's government and replaced local officials. The revolutionaries, who put Getúlio Vargas in power as president of Brazil, didn't face much resistance in Paraná. At this time, the state's finances were in trouble, and the economy was struggling.

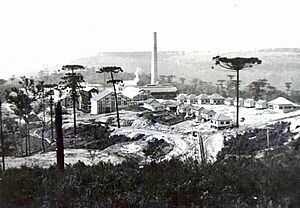

General Mário Tourinho was the first temporary governor, followed by Manuel Ribas. Ribas was elected in 1935 and stayed in office until 1945. During Vargas's time in power, Manuel Ribas was a strong supporter. He did important work like improving the Port of Paranaguá, setting up the Klabin paper mill, and building roads to connect cities. He also improved education and health. Ribas also allowed the creation of the Federal Territory of Iguaçu, which took land from western and southwestern Paraná. In 1943, Vargas visited the Klabin paper mill construction site, and the mill started working in 1946. In 1953, Vargas returned to Paraná to open the Presidente Vargas Hydroelectric Plant, built by Klabin.

In the late 1950s, the Colonos Revolt happened. This was a conflict where settlers protested problems with land ownership in the southwestern region. There were fights between settlers and land companies. People called "posseiros" (squatters) would settle on land they believed belonged to the state or had no owner. There were also many illegal land sales. By the 1960s, all the land in Paraná was occupied. These land conflicts continued throughout the second half of the 1900s, even as the economy and society grew.

Progress and Challenges

As the state government tried to make Paraná a major farming and wood-producing state, land conflicts continued and grew. Hundreds of thousands of small landowners and landless workers left the countryside, causing many towns to lose people. These people moved mainly to the Midwest and the Amazon regions, taking their skills with them.

In the early 1960s, Paraná suffered from drought, dry weather, and frosts. At this time, the state produced about half of Brazil's coffee. In 1963, Paraná was hit by one of the biggest wildfires in Brazil in the 1900s. The fire burned about 10% of the state, affecting 8,000 properties in 128 towns and killing over 100 people. After this, Paraná started a fire prevention plan with a special monitoring system. The state also began to grow different crops, especially after 1975, and started using more machines in farming.

Also in the 1960s, the Figueira Thermal Power Station began operating. It was the only power plant in the state that used only coal. This was meant to provide energy to the region and use the coal mines in Paraná.

The year 1975 was a tragic one for Paraná. During the winter, a strong cold air mass hit the state. Temperatures were extremely low, and there was heavy snowfall in Curitiba. In the early morning of July 18, 1975, a "black frost" occurred. This is when the sap inside plants freezes, killing them. The effects on farming were terrible, destroying crops, especially all the coffee production. This caused huge losses and an economic recession in Paraná.

In the 1960s and 1970s, soybean farming grew by thirty percent, replacing other crops like coffee. Industry also made big progress, with a bus and truck factory opening in Curitiba in 1976 and a refinery starting in 1977. Curitiba also began to make major improvements, becoming a model for new city planning. The first bike lanes were opened, and the express bus system appeared.

However, land disputes increased, even in Native American reserves. There were also complaints about serious environmental damage caused by the growing number of dams built for hydroelectric power plants on the Iguazu, Paranapanema, Capivari, and Paraná rivers. In 1980, the soybean harvest reached a record high, and Paraná became the top wheat producer in Brazil.

In 1982, the famous Guaíra falls disappeared because of the huge reservoir needed for the Itaipu dam. This caused strong protests. Land issues also worsened, with protests and actions by landless workers.

Stability and Development

Paraná is a state that attracts investments, partly because of its connection to Mercosur, a trade group. With its population growth now stable, the economy has become more modern and diverse in both farming and industry. The Itaipu Dam provides enough energy, and the Port of Paranaguá is an efficient place for exports.

Despite attracting investments, the state ended 1997 with a large financial deficit. This led to public works being stopped, and the government struggled to pay its bills. High interest rates and lower tax collection were some of the main reasons. In November 1999, the Palmas wind farm opened, which was the first of its kind in southern Brazil.

Political Changes

Before 1961, Moisés Lupion controlled Paraná's politics and was governor twice. He was followed by Ney Braga, who was also governor twice. José Richa was governor from 1982 to 1986. Then came elected governors Álvaro Dias (1987-1991) and Roberto Requião (1991-1994). In 1994, Jaime Lerner was elected and took office in January 1995. He was re-elected in 1998.

In 2000, Jaime Lerner privatized the Paraná State Bank (Banestado), following a national trend. In 2001, he tried to privatize the Paraná Electric Company (Copel), but people protested, and the plan was rejected. He also gave control of the Paraná Sanitation Company (Sanepar) to a private group.

21st Century

Roberto Requião won the elections in 2002 and became governor in 2003. To meet demands from the European market, Paraná created a law in 2003 that banned the planting, selling, and transporting of genetically modified seeds. However, the Supreme Federal Court later ruled this law unconstitutional. Still, the government prevented genetically modified crops from being shipped through the port of Paranaguá.

In 2005, a new law was passed that created a national commission to regulate the use of genetically modified organisms. In 2006, a court order allowed genetically modified soy to be shipped through Paranaguá. By 2008/2009, about 44% of the soy seeds in the state were modified. In October 2008, a Swiss company donated its farm in western Paraná to the state government. This farm, which had been occupied by the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), was to be used by the government as an experimental center for agroecology (ecological farming).

Requião remained governor until September 2006, when he left to run for re-election. He returned to office in 2007 after winning the election. In 2008, Beto Richa, José Richa's son, was re-elected mayor of Curitiba with a large majority.

Richa left the mayorship of Curitiba in early 2010 to run for state governor. Requião also resigned to run for the Federal Senate. In October 2010, Richa was elected governor. Also in 2010, a large embezzlement scheme was uncovered in the state's Legislative Assembly, involving "ghost employees" over 16 years.

Curitiba hosted some games of the 2014 FIFA World Cup at the Arena da Baixada stadium, which was renovated for the event.

In 2014, Klabin started the largest private investment ever in Paraná, a huge project that would last over ten years. In the same year, Beto Richa was re-elected governor. He stayed in office until April 2018, when Cida Borghetti took over and finished his term. She became the first woman to be governor of Paraná. She governed from April 6, 2018, to January 1, 2019. The current governor of Paraná is Ratinho Júnior, who was elected in 2018 and took office on January 1, 2019.

See also

- History of Brazil

- List of governors of Paraná