History of Strasbourg facts for kids

Strasbourg is a city in the historic Alsace region, located on the left bank of the Rhine river. It was founded by the Romans in 12 BC. Over time, it came under the control of the Merovingian kings and then became part of the Holy Roman Empire. The city grew and thrived during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In 1681, it was taken over by Louis XIV of France. Strasbourg's nationality changed four times between 1870 and 1945. Today, it stands as a symbol of friendship between France and Germany and European integration, meaning countries working together.

Contents

Ancient Times

People have lived in the area around Strasbourg for thousands of years. Archeologists have found ancient tools and items from the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages. Around 1300 BC, early Celtic people settled here permanently. By the late third century BC, it became a Celtic town with a market, called "Argentorate."

From Romans to Renaissance

Roman Argentoratum

The Romans, led by Nero Claudius Drusus, set up a military base called Argentoratum where Strasbourg is today. This name was first mentioned in 12 BC, and the city celebrated its 2,000th birthday in 1988. The Roman camp was destroyed by fire and rebuilt six times between the first and fifth centuries AD. From the year 90 AD, a Roman army group called the Legio VIII Augusta was always stationed there.

The main part of Roman Argentoratum was on the Grande Île, which is an island in the city. You can still see the outline of the Roman camp in the way the streets are laid out on the Grande Île. Many Roman items have also been found in the Koenigshoffen area, where large burial sites and civilian homes were located. In the fourth century, Strasbourg became the seat of a bishop, a leader of the church. Archeological digs have found parts of a church from the late fourth or early fifth century, which is thought to be the oldest church in Alsace.

In 357 AD, the Alemanni people fought the Battle of Argentoratum against the Romans. The Romans, led by Julian (who later became Emperor), defeated them. In 366 AD, the Alemanni crossed the frozen Rhine river to invade the Roman Empire. By the early fifth century, they had settled in what is now Alsace and parts of Switzerland.

Imperial City of Strassburg

Quick facts for kids

Imperial City of Strassburg

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1262–1681 | |||||||||

| Status | Imperial Free City | ||||||||

| Capital | Strasbourg | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

|

• City founded

|

12 BC | ||||||||

|

• Acquired by the Empire

|

923 1262 | ||||||||

|

• Gained Reichsfreiheit

|

1262 | ||||||||

|

• Straßburger Revolution

|

1332 | ||||||||

| 1681 | |||||||||

|

• Annexation recognised by the Holy Roman Empire

|

1697 |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

In the fifth century, Strasbourg was taken over by different groups: the Alemanni, the Huns, and the Franks. In the ninth century, it was known as Strazburg in the local language. This name appeared in the Oaths of Strasbourg in 842, an important text that showed the beginnings of the French and German languages.

Strasbourg became a major trading center. In 923, it came under the control of the Holy Roman Empire. For a long time, there was a conflict between the city's bishop and its citizens. The citizens won after the Battle of Hausbergen in 1262. As a result, the city was granted the status of a free imperial city, meaning it was largely independent within the Holy Roman Empire.

Around 1200, Gottfried von Strassburg wrote the famous story Tristan, a masterpiece of German medieval literature.

In 1332, a revolution led to a new city government where different guilds (groups of skilled workers) had a say. Strasbourg declared itself a free republic. In 1348, the terrible bubonic plague hit the city. This was followed by a very sad event on February 14, 1349, when several thousand Jewish people were publicly burned to death in one of the worst pogroms (attacks on a group of people) in history. Until the late 1700s, Jewish people were not allowed to stay in the city after 10 PM.

Construction on Strasbourg Cathedral began in the twelfth century and was finished in 1439. For a time, it was the tallest building in the world. A few years later, Johannes Gutenberg created the first European moveable type printing press in Strasbourg.

Printing and New Ideas

After Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press around 1440, the first printing shops outside his hometown of Mainz were set up in Strasbourg around 1460. In 1605, the first modern newspaper was published in Strasbourg. Printing helped new ideas, like humanism (a focus on human values and reason), to spread. Thinkers like Jakob Wimpheling and Sébastien Brant criticized church problems, which helped prepare the way for Protestantism.

In July 1518, an unusual event called the dancing plague of 1518 happened. About 400 people started dancing non-stop for weeks, and many died from exhaustion. In 1519, the ideas of Martin Luther were posted on the cathedral door, and the city leaders welcomed these changes.

Protestant Reformation

In the 1520s, during the Protestant Reformation, Strasbourg, guided by political leader Jacob Sturm von Sturmeck and religious leader Martin Bucer, adopted the teachings of Martin Luther. They established a school, which later became a university. The city first followed the Tetrapolitan Confession and then the Augsburg Confession. Some Protestant groups destroyed church decorations, even though Luther himself was against it.

Strasbourg's representatives protested at the Imperial Diet of Speyer (1529), which led to a split in the Catholic Church and the growth of Protestantism.

John Calvin, another important religious reformer, lived in Strasbourg as a refugee from 1538 to 1541. During this time, he worked on his famous book Institutes and published a Psalter (a book of psalms set to music).

Other early reformers in Strasbourg included Wolfgang Capito and Katharina Zell.

Thirty Years' War

The Free City of Strasbourg stayed neutral during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), keeping its status as a Free Imperial City. However, the city was later taken by Louis XIV of France to expand his kingdom.

Louis's advisors believed that if Strasbourg remained independent, it would threaten France's newly acquired lands in Alsace. They thought a military presence in Strasbourg was needed to protect these areas. Indeed, the bridge over the Rhine at Strasbourg had been used by enemy forces multiple times. In September 1681, Louis's forces surrounded the city with a huge army. After some talks, Louis marched into the city without a fight on September 30, 1681, and declared it part of France.

This takeover directly led to a short war. The French annexation of Strasbourg was officially recognized by the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697. The French government's policy of not allowing Protestants in France after 1685 was not strictly applied in Strasbourg and Alsace, as they had a special status. However, Strasbourg Cathedral was returned to the Catholics, though some other historic churches remained Protestant. The city's language also stayed mostly German. The German Lutheran university continued until the French Revolution. Famous students there included Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottfried Herder. The world's first school for midwives opened in Strasbourg in 1728.

At that time, only about 1% of Strasbourg's population spoke French.

French Revolution and "La Marseillaise"

News of the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, spread quickly. On July 21, the city hall was attacked. Strasbourg lost some of its properties. In 1790, the church's property was taken, and the university lost most of its income.

Things were calm until 1792, when France went to war against Prussia and Austria. During a dinner in Strasbourg on April 25, 1792, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle composed "War Song for the Army of the Rhine." This song was later renamed "La Marseillaise" and became France's national anthem. The same year, François Christophe Kellermann, who was from Strasbourg, became head of the Mosel Army. He led his troops to victory at the battle of Valmy, saving the young French republic.

During this time, Jean-Baptiste Kléber, also born in Strasbourg, led the French army to several important victories. A statue of Kléber now stands in the center of the city, at Place Kléber.

The mayor of Strasbourg, Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich, was executed in December 1793. Women were not allowed to wear traditional clothes, and Christian worship was forbidden.

Strasbourg's status as a free city was taken away by the French Revolution. Many churches and monasteries were destroyed or badly damaged. The cathedral lost hundreds of its statues. In April 1794, there was talk of tearing down its spire because it was seen as going against the idea of equality. However, the tower was saved when citizens put a giant tin Phrygian cap (a symbol of freedom) on top of it.

In 1797, the French army captured many German cities, which made Strasbourg safer, but the Revolution had caused a lot of disorder in the city.

Growth under Napoleon

At the end of 1799, Napoléon Bonaparte took power. He created new government offices, a commodity market (where goods are traded), and a chamber of commerce in Strasbourg. A new bridge was built over the Rhine, and roads were repaired. All these changes helped trade and business grow quickly.

Napoleon Bonaparte and his first wife, Joséphine, stayed in Strasbourg in 1805, 1806, and 1809. In 1810, his second wife, Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, spent her first night on French soil in the palace. Another royal visitor was King Charles X of France in 1828. In 1836, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte tried to start a coup (a sudden takeover of power) in Strasbourg, but he failed.

With the growth of factories and trade, the city's population tripled in the 1800s, reaching 150,000 people.

Franco-Prussian War

During the Franco-Prussian War and the Siege of Strasbourg, the city was heavily bombed by the Prussian army. The bombing was meant to break the spirit of the people. On August 24 and 26, 1870, the Museum of Fine Arts was destroyed by fire. The Municipal Library, which held unique medieval books and historical items, was also destroyed. The gothic cathedral was damaged, as were many other buildings and homes. By the end of the siege, 10,000 people were left without homes. Over 600 people died, including 261 civilians, and 3,200 were injured.

In 1871, after the war, Strasbourg became part of the new German Empire. It was made the capital of Alsace-Lorraine. As part of Imperial Germany, Strasbourg was rebuilt and expanded on a grand scale, with new areas like the Neue Stadt (new city). The University, which had been closed during the French Revolution, reopened in 1872 under a new name.

A ring of large fortifications (defensive structures) was built around the city. Most of these still stand today and are now named after French generals. These forts were later used by the French Army and as prisoner-of-war camps in 1918 and 1945.

Two churches were also built for the German army members: the Lutheran Église Saint-Paul and the Roman Catholic Église Saint-Maurice.

Between the World Wars (1918–1939)

After Germany's defeat in World War I, some revolutionaries declared Alsace-Lorraine an independent republic. On November 11, 1918, communist rebels even declared a "soviet government" in Strasbourg. French troops entered the city on November 22. A major street in the city is now named Rue du 22 Novembre to celebrate this day.

In 1919, following the Treaty of Versailles, Strasbourg became part of France again. Germans were expelled from the city, and some German monuments were destroyed. Most people in Strasbourg spoke the Alsatian dialect (90%) and wanted to keep their local laws. This period saw the rise of new political groups.

In 1920, Strasbourg became the home of the Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine, one of Europe's oldest organizations. Thanks to river trade, the city became prosperous again, which helped it during the economic crisis of the 1930s. New housing projects were built to house the growing number of workers.

The government also worked to develop the University of Strasbourg. Two historians, Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, started an important historical journal in 1929. Many foreign students came to the university.

When the Maginot Line (a line of fortifications) was built, Strasbourg's area was included as a fortified sub-sector. Blockhouses and casemates (small forts) were built along the Grand Canal d'Alsace and the Rhine river.

Second World War

Between September 1, 1939, and September 3, 1939, when France and Britain declared war against Germany, the entire city of Strasbourg (120,000 people) was evacuated. For ten months, the city was empty except for soldiers. The Jewish people of Strasbourg were evacuated to other French cities. The university was also moved.

After France fell to Germany in June 1940, Alsace was annexed by Germany. A strict policy of Germanization was put in place. When evacuees were allowed to return in July 1940, only people of Alsatian origin were permitted. The last Jewish people were deported on July 15, 1940. The main synagogue, a huge building completed in 1898, was set on fire and then torn down.

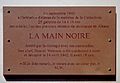

In September 1940, the first Alsatian resistance group was formed, called La main noire (the Black Hand). It was made up of 25 young men, aged 14 to 18, who attacked the German occupation. Their actions included an attack on the highest German commander of Alsace. In March 1942, Marcel Weinum, the leader, was caught by the Gestapo and sentenced to death at age 18. His last words were: "If I have to die, I shall die but with a pure heart."

From 1943, the city was bombed by Allied planes. In August 1944, several buildings in the Old Town were damaged, including the Palais Rohan and the Cathedral. On November 23, 1944, the city was officially liberated by the 2nd French Armoured Division led by General Leclerc. He had sworn that he would not stop fighting until the French flag flew over Strasbourg Cathedral.

Many people from Strasbourg were forced into the German Army against their will and sent to the Eastern Front. These young men and women were called Malgré-nous (meaning "against our will"). Many tried to escape or join the French Resistance, but it was very risky because their families could be sent to labor or concentration camps by the Germans. This threat forced most of them to stay in the German army. After the war, the few who survived were sometimes wrongly accused of being traitors because their situation was not understood in the rest of France.

Strasbourg as a Symbol of European Unity

In 1949, Strasbourg was chosen to be the home of the Council of Europe, which includes the European Court of Human Rights. Since 1952, the European Parliament has met in Strasbourg. This was officially confirmed in 1992 and made a treaty in 1997. However, only the main four-day meetings of the Parliament are held in Strasbourg each month. Other work is done in Brussels and Luxembourg. These meetings take place in the Immeuble Louise Weiss, which opened in 1999 and has the largest parliamentary assembly room in Europe. In 1992, Strasbourg also became the home of the Franco-German TV channel and movie company Arte.

In 1947, a fire broke out in the Musée des Beaux-Arts and destroyed many collections. This was an indirect result of the 1944 bombings, as humidity from the damaged buildings caused problems, and welding torches used to fix it started the fire.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city grew with new residential areas to solve housing shortages from war damage and population growth. Between 1995 and 2010, another new district was built.

In 1958, a severe hailstorm damaged the historical greenhouses of the Botanical Garden and many stained glass windows of St. Paul's Church.

In 2006, after careful restoration, the inner decoration of the Aubette building was opened to the public again. This decoration, created in the 1920s by Hans Arp, Theo van Doesburg, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, had been called "the Sistine Chapel of abstract art".

Images for kids

-

La belle Strasbourgeoise, by Nicolas de Largillière, 1703: elements of tracht and French fashions worn with aplomb, embody the independent culture of Strasbourg's high bourgeoisie

-

The Duke of Lorraine and Imperial troops crossing the Rhine at Strasbourg during the War of the Austrian Succession, 1744

-

1888 German map of Strasbourg as part of the German Empire

-

A lost, then restored, symbol of modernity in Strasbourg : a room in the Aubette building designed by Theo van Doesburg, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Estrasburgo para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Estrasburgo para niños

- Timeline of Strasbourg

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |