History of archaeology facts for kids

Archaeology is the study of human history through the things people left behind. This includes tools, buildings, bones, and even old landscapes. Archaeologists dig up and study these items to learn about past cultures.

People have been interested in the past for a long time. Kings wanted to show off their nation's history. In ancient times, like 550 BCE, King Nabonidus of Babylon dug up and fixed old buildings. The Greek historian Herodotus also studied old things. In China and India, scholars also looked at ancient artifacts. Later, in Europe, people called antiquarians collected old items. Over time, these collections became national museums. Archaeology then grew into a scientific way to study history in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The word "archaeology" first meant "ancient history" in general. By 1837, it started to mean the study of the past through digging and artifacts.

Contents

Early Discoveries and Explorers

Some of the earliest known "archaeologists" were kings and princes. Khaemweset, a son of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II, loved finding and fixing old Egyptian monuments. He worked on Djoser's step pyramid, which was built about 1,400 years before his time. Because of his work, some call him the "first Egyptologist".

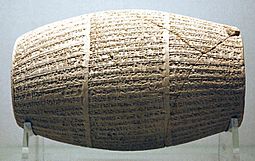

In ancient Mesopotamia, King Nabonidus of Babylon (around 550 BCE) found and studied a foundation stone from King Naram-Sin of Akkad (around 2200 BCE). Nabonidus is often called the first archaeologist. He led digs to find old temple foundations and then had them rebuilt. He was also the first to try and date an artifact, even though his guess was off by about 1,500 years.

The Greek historian Herodotus (around 484–425 BCE) was one of the first Western scholars to study the past in an organized way. He collected artifacts and checked if information was correct. He wrote nine books called Histories, describing different regions and events like the Greco-Persian Wars.

Antiquarians and Collectors

Later, archaeology was connected to the "antiquarian" movement. Antiquarians were people who studied history by looking at old artifacts, writings, and historical places. They were often wealthy and collected old items to display in their homes. These collections were sometimes called "cabinets of curiosities".

Antiquarians believed in studying real evidence from the past. Sir Richard Colt Hoare, an 18th-century antiquary, famously said, "We speak from facts not theory." This idea helped archaeology slowly become more scientific in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In Imperial China

During the Song dynasty (960–1279) in China, educated people became interested in collecting old art. Scholars wanted to use ancient items from the Shang dynasty, Zhou dynasty, and Han dynasty in state ceremonies.

However, some, like the scholar Shen Kuo (1031–1095), thought these items should be studied for how they worked. He wanted to learn about ancient manufacturing techniques. Other scholars, like Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072), made lists of ancient rubbings and bronzes. Zhao Mingcheng (1081–1129) said it was important to use old writings to fix mistakes in later history books.

Chinese antiquarian studies slowed down during the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) and Ming dynasty (1368–1644). They came back during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) but did not become a full scientific field like Western archaeology.

In Medieval India

In India, the 12th-century scholar Kalhana wrote about local traditions, old writings, coins, and buildings. His work, especially Rajatarangini (finished around 1150), is seen as one of the first history books of India and an early example of archaeological study.

In Renaissance Europe

In Europe, people became very interested in the remains of Greek and Roman civilizations during the Late Middle Ages. Flavio Biondo, an Italian historian in the early 15th century, created a guide to the ruins of ancient Rome. He is sometimes called an early founder of archaeology.

Another important figure was Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli (1391–around 1455). He traveled all over Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean. He wrote down his findings about ancient buildings and objects in a day-book called Commentaria. Historians have called him the "father of modern classical archaeology" because his records were very accurate.

English antiquarians like John Leland and William Camden in the 16th century surveyed the English countryside. They drew and described old monuments like standing stones. Many of these early researchers were clergymen who recorded local landmarks.

From Personal to National Collections

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, archaeology became a national effort. Personal collections of curiosities turned into large national museums. Countries hired people to find artifacts to make their national collections bigger. This also showed how powerful a nation was. For example, Giovanni Battista Belzoni collected ancient Egyptian items for Britain. In Mexico, the expansion of the National Museum of Anthropology helped create a grand image of Mexico's ancient past.

First Organized Digs

Some of the first places to be dug up were Stonehenge and other large stone monuments in England. Early digs at Stonehenge were done by William Harvey and Gilbert North in the early 1600s. John Aubrey was a pioneer who recorded many ancient sites in southern England. He also mapped the Avebury stone circle. He wrote Monumenta Britannica about Roman towns, hillforts, and castles. He also tried to figure out the ages of handwriting styles and medieval buildings.

William Stukeley also helped develop archaeology in the early 18th century. He studied Stonehenge and Avebury and is remembered as an important early archaeologist. He was one of the first to try and date these huge stone circles.

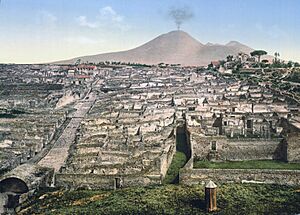

Excavations also started in the ancient towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum. These towns were buried by ash from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Digs began in Herculaneum in 1738 and in Pompeii in 1748. Finding whole towns, with tools and even human shapes, amazed people across Europe.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann was a very important figure in developing the scientific study of the past. He was called the "prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology." He was the first to use detailed study of art styles to understand ancient Greek and Roman history.

In America, Thomas Jefferson supervised the digging of a Native American burial mound on his land in Virginia in 1784. His methods were advanced for his time, but still simple compared to today's archaeology.

Napoleon's army carried out excavations during its Egyptian campaign (1798–1801). This was the first big overseas archaeological trip. Napoleon brought 500 scientists to study the ancient civilization. Jean-François Champollion later used the Rosetta stone to figure out hieroglyphics, which was key to studying Egypt.

However, early digs were often messy. People didn't understand the importance of layers of soil (stratification) or where things were found (context). For example, when Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin took the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon in Athens, people only cared about their beauty, not the information they held.

In the early 1800s, many other archaeological trips happened. People like Giovanni Battista Belzoni and Henry Salt collected Egyptian artifacts for the British Museum. Paul Émile Botta dug up an Assyrian palace. Austen Henry Layard found the ruins of Babylon and Nimrud. But the methods were still not very good. The main goal was to find cool artifacts and monuments.

Developing Modern Archaeology

William Cunnington (1754–1810) is called the father of archaeological excavation. He started digging in Wiltshire, England, around 1798. His work was paid for by Richard Colt Hoare. Cunnington carefully recorded his findings, especially from neolithic and Bronze Age burial mounds. He even used a trowel, which was a new tool for digging at the time.

One big step in the 19th century was understanding stratigraphy. This is the idea that different layers of soil represent different time periods. This idea came from geology, the study of Earth's layers. Archaeologists started using it to put artifacts in time order.

Another important idea was "deep time". Before this, many people thought the Earth was very young. James Ussher even calculated the world began on October 23, 4004 BCE. But later, Jacques Boucher de Perthes showed that the Earth and human history were much, much older.

Archaeology Becomes a Profession

Until the mid-1800s, archaeology was mostly a hobby for scholars. Britain's large empire gave many people a chance to dig up and study ancient things from other cultures.

Augustus Pitt Rivers was an army officer who helped turn archaeology into a serious science. In 1880, he started digging on his land, which had many Roman and Saxon artifacts. He dug for 17 seasons, using very careful methods. He is seen as the first scientific archaeologist. He was inspired by Charles Darwin's ideas about evolution. He organized artifacts by type and then by age. This helped show how human tools changed over time. He also insisted that all artifacts, not just pretty ones, should be collected and studied. This was a big change from just hunting for treasure.

William Flinders Petrie is another person called the Father of Archaeology. He was the first to scientifically study the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt in the 1880s. His careful study of the pyramid's structure helped disprove many wrong ideas about how it was built.

Petrie carefully recorded and studied artifacts in Egypt and later in Palestine. He believed that "the true line of research lies in the noting and comparison of the smallest details." He developed a way to date layers based on pottery, which changed how Egyptologists understood timelines. He also taught many future Egyptologists, including Howard Carter, who famously discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun.

One of the first big digs that became famous was at Hissarlik, the site of ancient Troy. Heinrich Schliemann and his team dug there in the 1870s. They found nine different cities built on top of each other. However, their methods were sometimes rough and damaged the site.

Meanwhile, Sir Arthur Evans dug at Knossos in Crete. He found an ancient advanced civilization called the Minoan civilization. Many of his finds went to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford for study. He also tried to rebuild parts of the site, which helped make archaeology more popular.

Modern Archaeology

Today, archaeology uses even more advanced methods and technology to study the past.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la Arqueología y del método arqueológico para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la Arqueología y del método arqueológico para niños

- Archaeology of Russia

- Archaeology of the Americas

- Council for British Archaeology

- History of anthropology

- Register of Professional Archaeologists

- List of Russian historians

- Outline of archaeology

- Typology (archaeology)

- Women in archaeology

- List of archaeological sites by country

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |