History of virology facts for kids

The history of virology is about how scientists discovered and learned about viruses. Viruses are tiny things that can cause infections. Even though people like Edward Jenner and Louis Pasteur made the first vaccines against viruses, they didn't know viruses existed.

The first hint of viruses came from experiments with special filters. These filters had holes small enough to stop bacteria. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovsky used such a filter. He showed that juice from a sick tobacco plant could still make healthy plants sick, even after being filtered.

Martinus Beijerinck later called this filtered, infectious stuff a "virus." This discovery is seen as the start of virology, which is the study of viruses. Later, Frederick Twort and Félix d'Herelle found bacteriophages, which are viruses that infect bacteria. This really helped the field grow.

By the early 1900s, many viruses had been found. In 1926, Thomas Milton Rivers said that viruses are "obligate parasites." This means they can only live and reproduce inside other living cells. Wendell Meredith Stanley showed that viruses are tiny particles, not just a fluid. Then, in 1931, the electron microscope was invented. This amazing tool finally let scientists see the complex shapes of viruses.

Contents

Pioneers in Virus Discovery

Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) was a very successful scientist. But he couldn't find what caused rabies. He thought it might be something too small to see with a microscope. In 1884, a French microbiologist named Charles Chamberland (1851–1931) invented a special filter. This filter had holes smaller than bacteria. This meant he could remove all bacteria from a liquid.

In 1876, Adolf Mayer was the first to show that "Tobacco Mosaic Disease" was infectious. He worked at an experimental farm in Wageningen. He thought a toxin or a tiny bacterium caused the disease. Later, in 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitry Ivanovsky (1864–1920) used a Chamberland filter. He was studying what we now call the tobacco mosaic virus.

Ivanovsky's tests showed that juice from sick tobacco plants could still infect healthy ones after being filtered. He thought a bacterial toxin might be the cause, but he didn't look into it further.

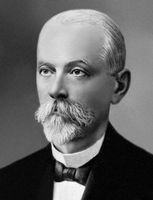

In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck (1851–1931) repeated Mayer's experiments. He taught microbiology in Wageningen. Beijerinck became sure that the filtered liquid held a new type of infectious agent. He saw that this agent only multiplied in cells that were dividing. He called it a contagium vivum fluidum (a soluble living germ) and brought back the word virus.

Beijerinck believed viruses were liquid. But later, American biochemist Wendell Meredith Stanley (1904–1971) proved they were actually particles. In the same year, 1898, Friedrich Loeffler (1852–1915) and Paul Frosch (1860–1928) found the first animal virus. They passed it through a similar filter and discovered what caused foot-and-mouth disease.

The first human virus found was the yellow fever virus. In 1881, Carlos Finlay (1833–1915), a Cuban doctor, suggested that mosquitoes carried the cause of yellow fever. This idea was proven in 1900 by a team led by Walter Reed (1851–1902). From 1901 to 1902, William Crawford Gorgas (1854–1920) organized the destruction of mosquito breeding spots in Cuba. This greatly reduced the disease. Gorgas later did the same in Panama, which helped open the Panama Canal in 1914. The virus itself was finally isolated by Max Theiler (1899–1972) in 1932. He then developed a successful vaccine.

By 1928, enough was known about viruses for Thomas Milton Rivers (1888–1962) to edit a book called Filterable Viruses. It covered all known viruses. Rivers had a great career in virology. In 1926, he famously said, "Viruses appear to be obligate parasites in the sense that their reproduction is dependent on living cells."

People thought viruses were particles, which fit well with the germ theory. Dr. J. Buist of Edinburgh might have been the first to see virus particles in 1886. He reported seeing "micrococci" in vaccine fluid. As microscopes got better, "inclusion bodies" were seen in many virus-infected cells. These were clumps of virus particles, but still too small to show much detail.

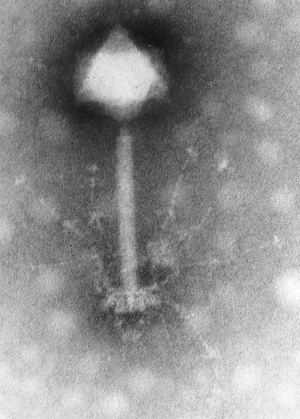

It wasn't until the electron microscope was invented in 1931 by German engineers Ernst Ruska (1906–1988) and Max Knoll (1887–1969) that virus particles could be seen clearly. They showed that bacteriophages, for example, had complex structures. The sizes of viruses seen with this new microscope matched what filtration tests had estimated. Viruses were expected to be small, but their wide range of sizes was a surprise. Some were almost as big as the smallest bacteria, while smaller ones were similar in size to complex organic molecules.

In 1935, Wendell Stanley studied the tobacco mosaic virus. He found it was mostly made of protein. In 1939, Stanley and Max Lauffer (born 1914) separated the virus into protein and nucleic acid. Stanley's colleague, Hubert S. Loring, showed this nucleic acid was specifically RNA. Finding RNA in virus particles was important. This is because in 1928, Fred Griffith (around 1879–1941) had shown that its "cousin," DNA, formed genes.

In Pasteur's time, and for many years after, "virus" meant any cause of infectious disease. Many bacteriologists soon found the causes of many infections. But some terrible infections remained, and no bacterial cause could be found. These agents were invisible and could only grow in living animals. The discovery of viruses helped us understand these mysterious infections.

Bacteriophages: Viruses that Attack Bacteria

How Bacteriophages Were Discovered

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect and multiply inside bacteria. They were found in the early 1900s by English bacteriologist Frederick Twort (1877–1950). But even before this, in 1896, bacteriologist Ernest Hanbury Hankin (1865–1939) reported something in the River Ganges water that could kill Vibrio cholerae. This bacterium causes cholera. The agent in the water could pass through filters that removed bacteria, but boiling destroyed it.

Twort discovered how bacteriophages affect staphylococci bacteria. He noticed that some colonies of these bacteria became watery when grown on agar. He collected some of these watery colonies and filtered them to remove the bacteria. He found that when this filtered liquid was added to fresh bacteria, they also became watery. He thought the agent might be "an amoeba, an ultramicroscopic virus, a living protoplasm, or an enzyme with the power of growth."

Félix d'Herelle (1873–1949) was a French-Canadian microbiologist. In 1917, he found an "invisible antagonist." When added to bacteria on agar, it created areas where bacteria died. This antagonist, now known as a bacteriophage, could pass through a Chamberland filter. He carefully diluted a sample of these viruses. He found that the most diluted samples, with the lowest virus amounts, didn't kill all bacteria. Instead, they formed distinct areas of dead organisms.

By counting these areas and multiplying by the dilution, he could figure out how many viruses were in the original sample. He realized he had found a new type of virus. He later created the term "bacteriophage." Between 1918 and 1921, d'Herelle found different types of bacteriophages. These could infect several other kinds of bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae.

Bacteriophages were once seen as a possible treatment for diseases like typhoid and cholera. But their promise was forgotten when penicillin was developed. Since the early 1970s, bacteria have become resistant to antibiotics like penicillin. This has led to new interest in using bacteriophages to treat serious infections.

Early Research on Bacteriophages (1920–1940)

D'Herelle traveled widely to promote using bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections. In 1928, he became a biology professor at Yale. He also started several research institutes. He was sure that bacteriophages were viruses. This was despite opposition from well-known bacteriologists like Nobel Prize winner Jules Bordet (1870–1961).

Bordet argued that bacteriophages were not viruses. He thought they were just enzymes released from "lysogenic" bacteria. He famously said, "the invisible world of d'Herelle does not exist." But in the 1930s, Christopher Andrewes (1896–1988) and others proved that bacteriophages were indeed viruses. They showed that these viruses differed in size and in their chemical and serological properties.

In 1940, the first electron micrograph (picture) of a bacteriophage was published. This silenced those who argued that bacteriophages were simple enzymes, not viruses. Many other types of bacteriophages were quickly found. They were shown to infect bacteria wherever they are found. Early research was stopped by World War II. D'Herelle, despite being a Canadian citizen, was held by the Vichy Government until the war ended.

Modern Era of Bacteriophage Study

Our knowledge of bacteriophages grew in the 1940s. This was thanks to the Phage Group, formed by scientists across the US. Max Delbrück (1906–1981) was a member. He started a course on bacteriophages at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Other key members included Salvador Luria (1912–1991) and Alfred Hershey (1908–1997).

In the 1950s, Hershey and Chase made important discoveries. They studied a bacteriophage called Enterobacteria phage T2. Their work helped explain how DNA replicates. Together with Delbruck, they won the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Their award was "for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses." Since then, studying bacteriophages has helped us understand how genes are turned on and off. They also provide a useful way to put foreign genes into bacteria. This has led to many basic discoveries in molecular biology.

Plant Viruses: A Threat to Crops

In 1882, Adolf Mayer (1843–1942) described a tobacco plant disease. He called it "mosaic disease." The sick plants had variegated (patchy) leaves that looked mottled. He ruled out a fungal infection and couldn't find any bacteria. He thought a "soluble, enzyme-like infectious principle" was involved. He didn't pursue this idea further.

It was the filtration experiments by Ivanovsky and Beijerinck that suggested the cause was a new infectious agent. After tobacco mosaic was recognized as a virus disease, many other plant virus infections were found.

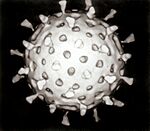

The tobacco mosaic virus is very important in virus history. It was the first virus found. It was also the first to be crystallized, and its structure was shown in detail. The first X-ray diffraction pictures of the crystallized virus were taken by Bernal and Fankuchen in 1941. Based on her pictures, Rosalind Franklin discovered the full structure of the virus in 1955.

In the same year, Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams showed something amazing. They found that purified tobacco mosaic virus RNA and its coat protein could put themselves together to form working viruses. This suggested that this simple process might be how viruses are made inside their host cells.

By 1935, many plant diseases were thought to be caused by viruses. In 1922, John Kunkel Small (1869–1938) found that insects could act as vectors. This means they could carry and transmit viruses to plants. In the next ten years, many plant diseases were shown to be caused by viruses carried by insects. In 1939, Francis Holmes, a pioneer in plant virology, described 129 viruses that caused plant diseases.

Modern farming, with its large fields of one crop, creates a good environment for many plant viruses. In 1948, in Kansas, US, 7% of the wheat crop was destroyed by wheat streak mosaic virus. Tiny mites called Aceria tulipae spread this virus.

In 1970, Russian plant virologist Joseph Atabekov found that many plant viruses only infect one type of host plant. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses now recognizes over 900 plant viruses.

20th Century: A Golden Age of Discovery

By the end of the 1800s, viruses were defined by three things: their ability to infect, their ability to pass through filters, and their need for living hosts. Until this time, viruses had only been grown in plants and animals. But in 1906, Ross Granville Harrison (1870–1959) invented a way to grow tissue in lymph.

In 1913, E Steinhardt, C Israeli, and RA Lambert used this method. They grew vaccinia virus in pieces of guinea pig eye tissue. In 1928, HB and MC Maitland grew vaccinia virus in suspensions of chopped hens' kidneys. Their method wasn't widely used until the 1950s. That's when poliovirus was grown on a large scale for vaccine production. In 1941–42, George Hirst (1909–94) developed tests. These tests used hemagglutination to measure many viruses and virus-specific antibodies in blood.

Influenza: The Flu Virus

The influenza virus that caused the terrible 1918–1919 flu pandemic wasn't found until the 1930s. But descriptions of the disease and later research proved it was to blame. This pandemic killed 40–50 million people in less than a year.

The proof that a virus caused it didn't come until 1933. Haemophilus influenzae is a bacterium that often infects people after the flu. This led the famous German bacteriologist Richard Pfeiffer (1858–1945) to wrongly think this bacterium caused influenza. A big step forward came in 1931. American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture grew influenza and other viruses in fertilized chicken eggs.

Hirst found an enzyme activity linked to the virus particle. This was later identified as neuraminidase. It was the first time an enzyme was shown to be part of a virus. Frank Macfarlane Burnet showed in the early 1950s that the virus changes very often. Hirst later figured out that it has a segmented genome, meaning its genetic material is in pieces.

Poliomyelitis: The Polio Virus

In 1949, John F. Enders (1897–1985), Thomas Weller (1915–2008), and Frederick Robbins (1916–2003) grew polio virus for the first time. They used cultured human embryo cells. This was the first virus grown without using solid animal tissue or eggs.

Infections by poliovirus usually cause very mild symptoms. This wasn't known until the virus was isolated in cultured cells. Then, it was found that many people had mild infections that didn't lead to poliomyelitis (the severe form of polio). But, unlike other viral infections, the number of polio cases increased in the 20th century. It reached its highest point around 1952. The invention of a cell culture system to grow the virus allowed Jonas Salk (1914–1995) to make an effective polio vaccine.

Epstein–Barr Virus: A Link to Cancer

Denis Parsons Burkitt (1911–1993) was an Irish doctor. He was the first to describe a type of cancer now named after him: Burkitt's lymphoma. This cancer was common in children in equatorial Africa in the early 1960s.

To find the cause, Burkitt sent tumor cells to Anthony Epstein (born 1921), a British virologist. Epstein, along with Yvonne Barr and Bert Achong (1928–1996), after many tries, found viruses in the fluid around the cells. These viruses looked like herpes viruses. The virus was later shown to be a new herpes virus, now called Epstein–Barr virus.

Surprisingly, Epstein–Barr virus is very common but usually causes a mild infection in Europeans. Why it causes such a serious illness in Africans is not fully understood. But reduced immunity due to malaria might be a reason. Epstein–Barr virus is important because it was the first virus shown to cause cancer in humans.

Late 20th and Early 21st Century Discoveries

The second half of the 20th century was a golden age for finding new viruses. Most of the 2,000 known types of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years. In 1946, bovine virus diarrhea was found. It's still probably the most common disease in cattle worldwide. In 1957, equine arterivirus was discovered.

In the 1950s, better ways to isolate and detect viruses led to finding several important human viruses. These include varicella zoster virus (chickenpox), the paramyxoviruses (like measles virus and respiratory syncytial virus), and the rhinoviruses that cause the common cold. More viruses were found in the 1960s. In 1963, the hepatitis B virus was discovered by Baruch Blumberg (born 1925).

Reverse transcriptase is a key enzyme that retroviruses use to turn their RNA into DNA. It was first described in 1970, independently by Howard Temin and David Baltimore (born 1938). This was important for developing antiviral drugs, a major turning point in the history of viral infections. In 1983, Luc Montagnier (born 1932) and his team in France first isolated the retrovirus now called HIV. In 1989, Michael Houghton's team discovered hepatitis C.

New viruses and virus strains were found in every decade of the late 20th century. These discoveries have continued into the 21st century. New viral diseases like SARS and nipah virus have appeared. Even with all the scientists' achievements over the past hundred years, viruses continue to bring new threats and challenges.

| Year | Virus | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1908 | poliovirus | |

| 1911 | Rous sarcoma virus | |

| 1915 | bacteriophage of staphylococci | |

| 1917 | bacteriophage of shigellae | |

| 1918 | bacteriophage of salmonellae | |

| 1927 | yellow fever virus | |

| 1930 | western equine encephalitis virus | |

| 1933 | eastern equine encephalitis virus | |

| 1934 | mumps virus | |

| 1935 | Japanese encephalitis virus | |

| 1943 | Dengue virus | |

| 1949 | enteroviruses | |

| 1952 | Varicella zoster virus | |

| 1953 | adenovirus | |

| 1954 | measles virus | |

| 1956 | paramyxoviruses, rhinovirus | |

| 1958 | monkeypox | |

| 1962 | rubella virus | |

| 1963 | hepatitis B virus | |

| 1964 | Epstein–Barr virus | |

| 1965 | retroviruses | |

| 1966 | Lassa fever virus | |

| 1967 | Marburg virus | |

| 1972 | norovirus | |

| 1973 | rotavirus, hepatitis A virus | |

| 1975 | parvovirus B19 | |

| 1976 | Ebola virus | |

| 1980 | human T-lymphotropic virus 1 | |

| 1982 | human T-lymphotropic virus 2 | |

| 1983 | HIV | |

| 1986 | human herpesvirus 6 | |

| 1989 | hepatitis C virus | |

| 1990 | hepatitis E virus, Human herpesvirus 7 | |

| 1993 | hantavirus | |

| 1994 | henipavirus | |

| 1997 | Anelloviridae |

See also

- List of viruses

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |