James Ohio Pattie facts for kids

James Ohio Pattie (born around 1804 – died around 1850) was an American explorer and writer from Kentucky. He was known as a "frontiersman," which means he was an adventurer who explored new, wild lands.

From 1824 to 1830, Pattie went on many trips to trap furs and trade. He traveled across the American West and Southwest, even going into what is now northern and central Mexico.

In 1831, Pattie worked with a newspaper writer named Timothy Flint. They published a book called The Personal Narrative of James O. Pattie of Kentucky. This book told the story of Pattie's travels. Historians like the book because it describes the Southwest so well. However, they aren't sure if everything Pattie wrote is completely true. While the main events likely happened, Pattie probably made his own role in them sound more important.

Contents

Pattie's Amazing Journeys

1824–1826: Rivers and Trapping

In June 1824, James Pattie and his father, Sylvester, left St. Louis. They traveled along the Missouri River to trade with Native American tribes. When they reached a military camp at Council Bluffs, they learned they needed a special permit to go further.

Instead of going back to St. Louis, Pattie's father decided to join a group heading to Santa Fe. This group was led by Sylvester Pratte and had 116 men with over 300 horses and mules. Because of his military past, Pattie's father was asked to lead this large group.

They arrived in Santa Fe in November 1825. There, they asked the governor for permission to trap beaver along the Gila River. At first, the governor said no. James Pattie later claimed they got the license after saving the governor's daughter from some Mescalero Apache people. But this story was probably made up. The Patties likely started trapping along the Gila River without permission.

From Santa Fe, Sylvester, James, and three guides went south along the Rio Grande. Then they turned west towards the Santa Rita copper mines. They stopped there briefly for supplies. They spent the winter trapping beaver on the Gila River, going as far west as Phoenix, Arizona. But they didn't have much luck.

The group faced bears, small groups of Native Americans, and times of sickness and hunger. By early 1826, they were so hungry they had to eat their own horses and even a grizzly bear. Their luck changed in early 1826. By late March, they had hidden hundreds of beaver furs along the river. They hoped to come back for them later when they had animals to carry the heavy load.

In April, the Patties returned to the Santa Rita mine. The owner offered Sylvester control of the mine's operations. Pattie's father managed the mine well with two partners until 1827. This left James to trap on his own.

1826–27: Colorado River Adventures

In June 1826, Pattie said he joined a trip down the Gila River to get the hidden furs. While this trip did happen, Pattie was probably not there. He was a witness to a document signed at the mine on June 14. The group came back in early July without any furs. They found that Native Americans had taken the hidden furs, which were worth a lot of money.

The next trapping season was still months away. So, Pattie worked at the mine during the summer of 1826. He earned one dollar a day for protecting the mine from Apache attacks. Pattie learned many useful skills from the different people he met at Santa Rita. He said he learned to speak Spanish in a few months from Juan Onis. Pattie became good enough at Spanish to work as an interpreter later on. He also learned to tell the different Native American tribes apart. This was very helpful on his next trapping trip.

Even though his father wanted him to stay at the mine, Pattie left in January 1827. He planned to travel the Gila River to where it met the Colorado River. The group spent a few days in a Yuma village at the mouth of the Colorado. They gathered supplies there. Then they went several miles up the river. There, they met and traded with a group of Maricopa Native Americans.

A week later, the group met some Mohave people. Pattie and another trapper, George Yount, had heard about them and thought they might be unfriendly. The Mohave did attack Pattie's group the morning after they arrived. But the Mohave were easily forced to leave.

After the fight with the Mohave, Pattie's story about his trip becomes unclear. This is strange, especially considering how far he said they traveled. He claimed they went along the Colorado River into Navajo land. Then, he said they crossed the Continental Divide (a line of mountains that separates rivers flowing to different oceans). After that, he claimed they went north, trapping along the Platte, Bighorn, and Yellowstone rivers. Pattie even said the group went as far north as the Clark Fork of the Columbia River in Montana. Finally, he claimed they reached a Zuni village in western New Mexico. This journey would be about 2000 miles in just 85 days, which is almost certainly not true. Pattie was probably just naming rivers he had heard about from other trappers. The group likely only left the Colorado River for a short time when they reached the huge Grand Canyon.

When the group reached the Zuni village, several members had died. The survivors were very hungry. However, the trip was a huge success because they returned with furs worth almost $20,000. But when the group returned to Santa Fe in August, soldiers took their furs. The governor in Santa Fe said the group had been trapping without a license.

1827–28: More Rivers and Trouble

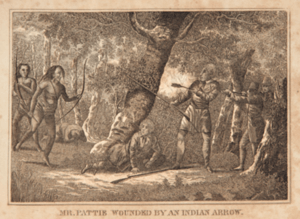

The exact dates Pattie gave for his travels in the spring and summer of 1827 are confusing. But he did lead a short hunting trip along the Pecos River after arriving in Santa Fe. He wanted to replace some of the goods he had lost. This Pecos trip included Pattie and fifteen other Americans. They were attacked by Native Americans, whom Pattie correctly identified as Mescalero Apache. Most of the group survived, but Pattie was wounded in his hip and chest by arrows. On the way back, the group met some Navajo people who were tracking the Mescalero. A Navajo medicine man treated Pattie's wounds.

The group successfully avoided the governor after returning to Santa Fe. They made a good profit from selling their furs. From there, they went back to Santa Rita. Soon after, a Spanish bookkeeper stole $30,000 from Pattie's father. This left the Patties with no money. In September 1827, Sylvester got a special travel document called a passport in Santa Fe. The Patties planned to use it to reach California.

On their way down the Gila River to California, half of the trappers left the group. Every animal they had for carrying supplies either died, got lost, or was stolen by the same Yuma Native Americans who had been kind to Pattie the year before. The remaining eight members of the trip built simple boats. They floated down the Colorado River until they reached the Gulf of California. The strong waves there forced the Patties to leave their boats a few miles upriver. They had collected hundreds of furs, worth between $25,000 and $30,000. They hid these furs near the river in February 1827.

The group then traveled west, stopping at several Spanish towns and missions. They asked to buy horses to get their hidden furs. Instead, they were taken to San Diego in late spring 1828. There, the Patties were held and questioned by the California governor, José Maria de Echeandia.

1828–29: Being Held Captive

When they arrived in San Diego, the Patties and their group had their weapons taken away. They were put in prison because the governor thought their passport might be fake. Pattie's father had been sick before they arrived, and he got worse in prison. Sylvester died on April 24 and was buried soon after. He was the first American known to be buried in California.

After his father died, James worked as a translator between Governor Echeandia and John Bradshaw. Bradshaw was the captain of an American ship called the Franklin. He had offered to buy Pattie's furs if they could be found. Echeandia agreed to let the trappers go back for the furs. But Pattie had to stay in San Diego as a hostage (someone held to make sure others keep a promise). While waiting for the group, Pattie told Bradshaw the story of his travels, being held captive, and his father's death. Pattie's short story was published a year later in a St. Louis newspaper. This was the first news his family had heard about him since 1824.

Only three members of the original group survived and returned to San Diego several weeks later. A spring flood had washed away all the hidden furs. The traps they found were sold to pay for the horses and mules they had used. Pattie claimed they were again disarmed and put in prison. But this was probably an exaggeration. However, Echeandia did make the trappers stay in San Diego. He did not let Pattie leave the city until February or March 1829, almost a year after he arrived.

1829–30: California Coast Travels

Pattie said that Governor Echeandia released him because of a sickness outbreak in the winter of 1828–29. He claimed the governor hired him to give shots to every Californian along the Pacific coast to prevent the sickness. While there had been a recent widespread sickness in California, it was measles, not smallpox. Also, the outbreak started in October 1827, before Pattie arrived in San Diego, and it had ended by June 1828.

It's more likely that Pattie heard about the sickness and made himself a hero in his story. The vaccination story makes Pattie's travels in California sound brave. But he probably spent much of that year without money. He traveled north with his three remaining friends to Los Angeles. There, everyone except Pattie quickly settled down and married into Catholic Californian families.

Pattie spent the rest of 1829 exploring the coast of California. While his claims of giving shots to people are likely false, his descriptions of the missions and towns in the area are detailed and accurate. Pattie traveled as far north as the Russian settlement of Fort Ross, which was about 90 miles north of San Francisco. Then he returned south to Monterey to find a ship to Mexico.

In November 1829, a group of people wanting change, led by Joaquin Solis, started a small uprising in Monterey. They traveled south to meet Governor Echeandia's army at Santa Barbara. Solis's group was defeated, and he was captured and sent back to Monterey. Pattie accurately wrote about these events. However, he falsely claimed that he led the group that captured Solis. In reality, Pattie was not involved in the uprising. He spent months in Monterey waiting for a passenger ship. During this time, he hunted otters nearby. He earned $300, which helped pay for part of his journey.

In March 1830, an American official named John Coffin Jones arrived in Monterey on a ship called the Volunteer. Jones allowed Pattie to join the ship. He also offered to take Solis and other leaders of the uprising to Mexico City for trial. Pattie met with Echeandia one more time to complain about his past imprisonment and get a passport for Mexico. Echeandia understood Pattie's complaints but said he was only following the law. Still, he gave Pattie his passport. The Volunteer left Monterey on May 9, 1830.

1830: Mexico and Return Home

Nine days after leaving Monterey, the Volunteer arrived in San Blas, Mexico. Pattie did not go on any more expeditions in Mexico. But he planned to stop in Mexico City to try and get money for being held captive by Echeandia. When he reached Mexico City in early June, Pattie met with the American diplomat, Anthony Butler. Butler showed Pattie a letter from the American Secretary of State, Martin Van Buren. Van Buren had asked Butler to try to free Pattie from prison.

Butler arranged a meeting with Mexican President Anastasio Bustamente. Pattie could officially share his complaints there. President Bustamente felt bad for Pattie. But he did not offer him any money. However, he did tell Pattie that Echeandia had been replaced as governor because of some bad actions.

President Bustamente gave Pattie a passport to return home through the port of Vera Cruz. Pattie had almost no money when he arrived in Vera Cruz. But the American official there, Isaac Stone, arranged for him to travel for free to the U.S.. On July 17, 1830, Pattie boarded the ship United States heading for New Orleans.

The day after Pattie arrived in New Orleans, a newspaper called the Louisiana Advertiser announced his return. Again, Pattie did not have enough money to travel the rest of the way to Kentucky. But Louisiana Senator Josiah Johnston offered to pay for his trip up the Mississippi River. Johnston had grown up near Pattie's father and knew some of Pattie's family. Pattie traveled on a steamboat called the Cora.

Pattie's Book and Later Life

While Pattie was on his way back home to Augusta, Kentucky, Senator Johnston introduced him to a newspaper writer named Timothy Flint in Cincinnati. Pattie and Flint agreed to meet later so Pattie could tell his travel stories.

Pattie returned to Augusta on August 30, 1830. The next year, Flint published The Personal Narrative of James O. Pattie of Kentucky. This was Pattie's story about his time in the Southwest. Even though Flint was a successful writer, the book didn't get much attention. A newspaper called the Cincinnati Mirror only briefly mentioned it, calling it "interesting."

We don't know much about the rest of Pattie's life. For a while, he went to Augusta College in Kentucky. The last official record of Pattie is on a tax list for Bracken County, Kentucky, in 1833. It shows he owned two horses worth $75 together. A California politician named William Waldo claimed he met Pattie in the Sierra Nevada mountains in 1849 during the Gold Rush. But no one has ever proven this claim.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |