Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount |

|

|---|---|

Southeast of the island of Hawaiʻi, Hawaii, U.S.

|

|

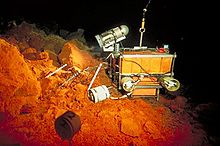

Yellow iron oxide-covered lava rock on the flank of Kamaʻehuakanaloa

|

|

| Summit depth | 3,200 ft (975 m). |

| Height | over 10,000 ft (3,000 m) above the ocean floor |

| Summit area | Volume – 160 cu mi (670 km3) |

| Translation | "glowing child of Kanaloa" (from Hawaiian) |

| Location | |

| Location | Southeast of the island of Hawaiʻi, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 18°55′N 155°16′W / 18.92°N 155.27°W |

| Country | United States |

| Geology | |

| Type | Submarine volcano |

| Volcanic arc/chain | Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain |

| Age of rock | At least 400,000 years old |

| Last eruption | February to August 1996 |

| History | |

| Discovery date | 1940 – US Coast and Geodetic Survey chart number 4115 |

| First visit | 1978 |

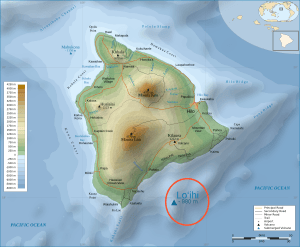

Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount (formerly called Lōʻihi) is an active submarine volcano, which means it's an underwater volcano. It's located about 35 km (22 mi) off the southeast coast of the island of Hawaii. The very top of this seamount is about 975 m (3,200 ft) below the sea level.

Kamaʻehuakanaloa sits on the side of Mauna Loa, which is the largest shield volcano on Earth. It is the newest volcano in the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain. This chain is a long line of volcanoes stretching about 6,200 km (3,900 mi) northwest from Kamaʻehuakanaloa.

Most active volcanoes in the Pacific Ocean are found where Earth's plates meet. But Kamaʻehuakanaloa and the other Hawaiian volcanoes are different. They are hotspot volcanoes, meaning they formed far away from any plate boundary. These volcanoes grow from the Hawaii hotspot, a super-hot spot deep inside Earth. As the youngest volcano in this chain, Kamaʻehuakanaloa is still in its early underwater stage of growth.

Kamaʻehuakanaloa started forming around 400,000 years ago. Scientists believe it will rise above sea level in about 10,000 to 100,000 years. Its summit is over 3,000 m (10,000 ft) above the seafloor. That makes it taller than Mount St. Helens was before its huge eruption in 1980. Many tiny living things, called microbes, live around Kamaʻehuakanaloa's hydrothermal vents.

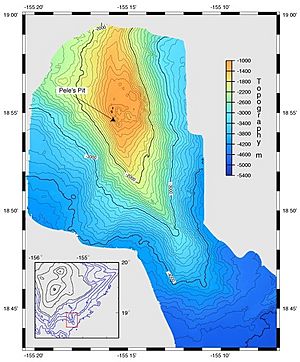

In the summer of 1996, more than 4,000 earthquakes happened at Kamaʻehuakanaloa. This was the biggest group of earthquakes ever recorded in Hawaii at that time. The quakes changed about 10 to 13 km2 (4 to 5 sq mi) of the seamount's top. One area, called Pele's Vents, completely fell in and became Pele's Pit. The volcano has been somewhat active since 1996. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) keeps an eye on it.

Contents

Naming the Volcano

The name Kamaʻehuakanaloa comes from the Hawaiian language. It means "glowing child of Kanaloa", who is the Hawaiian god of the ocean. This name was found in old Hawaiian songs and stories. The Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names officially gave it this name in 2021. The U.S. Geological Survey also adopted it.

Before 2021, from 1955, the seamount was called "Lōʻihi". This Hawaiian word means "long", which described its shape. The name was changed to Kamaʻehuakanaloa to respect native Hawaiian traditions for naming places.

About the Volcano

How Kamaʻehuakanaloa Formed

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is a seamount, which is an underwater volcano. It sits on the side of Mauna Loa, the Earth's largest shield volcano. Kamaʻehuakanaloa is the newest volcano made by the Hawaiʻi hotspot. This hotspot is a very hot spot deep in Earth that creates the Hawaiian volcanoes.

The top of Kamaʻehuakanaloa has three pit craters. These are bowl-shaped holes. There are also two long rift zones, which are cracks where lava can flow out. One rift zone goes north for about 11 km (7 mi). The other goes south-southeast for about 19 km (12 mi).

The pit craters are called West Pit, East Pit, and Pele's Pit. Pele's Pit is the newest. It formed in July 1996 when an area called Pele's Vent collapsed. This happened during a big earthquake swarm. The walls of Pele's Pit are 200 m (700 ft) high. They are also very thick, which suggests lava has filled the crater many times.

The long rift zones give Kamaʻehuakanaloa its stretched-out shape. This is why its old name, "Lōʻihi," meant "long." Scientists have seen that these rift zones don't have much dirt covering them. This means they have been active recently.

Before 1970, people thought Kamaʻehuakanaloa was an old, inactive volcano. They thought it had moved to its current spot because of sea-floor spreading. This is when new ocean floor forms and pushes older parts away. But in 1970, scientists studied some earthquakes near Hawaii. They found that Kamaʻehuakanaloa was actually an active volcano in the Hawaiian chain.

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is built on the seafloor. Its northern base is 1,900 m (2,100 yd) below sea level. Its southern base is much deeper, at 4,755 m (15,600 ft) below the surface. This means the volcano is taller when measured from its southern base.

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is growing just like all other Hawaiian volcanoes. Studies of its lava show it's changing from an early underwater stage to a shield volcano stage. In its early stage, Hawaiian volcanoes have steeper sides and are less active. They produce a certain type of lava. Scientists expect that more eruptions will eventually make Kamaʻehuakanaloa an island.

The volcano often has landslides. As it grows, its sides become unstable. Large amounts of rock and dirt slide down its steep southeastern face. These landslides are an important part of how Hawaiian volcanoes develop. Scientists predict Kamaʻehuakanaloa will rise above the ocean surface in 10,000 to 100,000 years.

How Old is Kamaʻehuakanaloa?

Scientists use Radiometric dating to find the age of rocks from Kamaʻehuakanaloa. This method looks at how certain elements in the rock have changed over time. The oldest rock found is about 300,000 years old. Based on these samples, scientists believe Kamaʻehuakanaloa is about 400,000 years old.

The volcano grows by adding new rock. It grows about 3.5 mm (0.14 in) per year near its base. Near the top, it grows faster, about 7.8 mm (0.31 in) per year. If it grows like other volcanoes, 40% of its total size formed in the last 100,000 years.

Hawaiian volcanoes slowly move northwest. Kamaʻehuakanaloa moves about 10 cm (4 in) each year. This means when it first erupted, it was about 40 km (25 mi) southeast of where it is now.

Volcano Activity

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is a young and active volcano. However, it's not as active as nearby Kīlauea. Over the past few decades, many earthquake swarms have happened at Kamaʻehuakanaloa. An earthquake swarm is a series of many earthquakes in one area over a short time.

Scientists have been recording its activity since 1959. Most earthquake swarms at Kamaʻehuakanaloa last less than two days. The two longest were in 1990-1991 and 1996. The 1996 event was shorter but much stronger.

During the 1996 event, a special device on the ocean floor recorded the earthquakes. It showed that the quakes were happening 6 km (4 mi) to 8 km (5 mi) below the summit. This is where Kamaʻehuakanaloa's magma chamber is. This proves that the earthquakes are caused by the volcano's activity.

Since 1959, Kamaʻehuakanaloa has had a low level of seismic activity. This means two to ten earthquakes are linked to its summit each month. These small quakes help scientists study how rocks carry seismic waves. They also help understand the link between earthquakes and eruptions.

Sometimes, there are large swarms of hundreds of earthquakes. Most of these earthquakes happen in the southwest part of Kamaʻehuakanaloa. The biggest swarms were in 1971, 1972, 1975, 1991–92, and 1996.

The 1996 Earthquake Swarm

| Year(s) | What Happened |

|---|---|

|

|

An eruption happened in early 1996. Then, a very large earthquake swarm occurred from July 16 to August 9. |

|

|

A device on the seamount found signs that magma might have moved away, possibly causing the ground to sink. |

|

|

A possible eruption happened on September 20. |

|

|

Nine earthquakes with a strength of 3.0 to 4.2 were recorded from November 1984 to January 1985. An eruption might have happened, but it's not certain. |

|

|

A big earthquake swarm occurred from August to November. |

|

|

A possible eruption happened from September 1971 to September 1972. It's not certain. |

|

|

An earthquake swarm in 1952 first made scientists notice the volcano. Before this, they thought it was extinct. |

|

± 1000 |

An ancient eruption was confirmed. |

|

± 1000 |

An ancient eruption was confirmed. |

|

± 1000 |

An ancient eruption was confirmed, likely on the east side. |

| This table lists only possible eruptions and major events. Kamaʻehuakanaloa also has many smaller earthquake swarms almost every six months. | |

The biggest activity recorded at Kamaʻehuakanaloa was a swarm of 4,070 earthquakes. These happened between July 16 and August 9, 1996. This was the largest and strongest series of earthquakes ever recorded for any Hawaiian volcano at that time. Most of the earthquakes were not very strong, less than 3.0 on the Moment magnitude scale. But several hundred were stronger than 3.0, and over 40 were stronger than 4.0. One even reached 5.0.

Scientists quickly sent a research team in August 1996 to study the end of the earthquake swarm. They found that an eruption had happened before the earthquakes.

Later studies showed that the southern part of Kamaʻehuakanaloa's summit had collapsed. This was due to the earthquakes and magma moving away from the volcano. A new crater formed, about 1 km (0.6 mi) wide and 300 m (330 yd) deep. About 100 million cubic meters of volcanic material moved. An area of 10 to 13 km2 (3.9 to 5.0 sq mi) on the summit changed. It became covered with huge pillow lava blocks, some as big as buses.

An area called "Pele's Vents" completely collapsed into a giant pit, which was renamed "Pele's Pit." Strong ocean currents make it dangerous for submersibles to dive in this area.

Researchers saw clouds of sulfide and sulfate in the water. The collapse of Pele's Vents released a lot of hot water and minerals. The mix of materials suggested temperatures over 250 °C (482 °F). This was a record for an underwater volcano. The materials were similar to those found in black smokers, which are hot vents along mid-ocean ridges.

These studies showed that the most active areas for volcanoes and hot vents were along the southern rift. Dives on the less active northern side showed that the ground there was more stable. New hot vents, called Naha Vents, were found in the upper-south rift zone.

Recent Activity

Kamaʻehuakanaloa has been mostly quiet since the 1996 event. No activity was recorded from 2002 to 2004. But in 2005, the seamount showed signs of life again. It had an earthquake bigger than any recorded there before. The USGS reported two earthquakes, magnitudes 5.1 and 5.4, in May and July. Both started deep, at 44 km (27 mi).

In April, a magnitude 4.3 earthquake was recorded at about 33 km (21 mi) deep. From December 2005 to January 2006, about 100 earthquakes occurred. The largest was magnitude 4. Another earthquake, magnitude 4.7, was recorded between Kamaʻehuakanaloa and Pāhala on the island of Hawaii.

Exploring the Volcano

Early Discoveries

| Date | What Was Studied (mostly on R/V Kaʻimikai-o-Kanaloa and with Pisces V) |

|---|---|

| 1940 | Kamaʻehuakanaloa first appeared on a map by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey. |

| 1978 | An expedition studied strong earthquake activity. This was the first clear sign that the volcano was active. |

| 1979 | More samples were collected, which seemed to confirm the 1978 findings. |

| 1980 | Many hot vents were found, giving more evidence. The first detailed maps of the seafloor were made. |

| 1987 | Several hot vent areas were marked and studied. |

| August 1996 | Emergency dives were made by a team led by Frederick Duennebier, reacting to the strong activity. |

| Early Sept. 1997 | Studies of hot vents were done. |

| Late August 1997 | Geological studies of recent eruptions at Kamaʻehuakanaloa were carried out. |

| October 1997 | The HUGO observatory was put in place. |

| September–October 1998 | Many dives were made by different science teams to visit New Pit, the Summit Area, and HUGO. |

| January 1998 | HUGO was visited again. |

| October 2002 | HUGO was taken out of the ocean. |

| October 2006 October 2007 October 2008 October 2009 |

FeMO (Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory) trips investigated iron-oxidizing microbes at Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Much was learned about the microbes living there. |

Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount first appeared on a map in 1940. This map showed the depths of the ocean floor near Hawaii. At that time, it was just one of many seamounts. A large earthquake swarm in 1952 first drew attention to it. That same year, a geologist named Gordon A. Macdonald thought it might be an active underwater shield volcano. He believed it was the newest volcano created by the Hawaiʻi hotspot.

Scientists suspected it was an active undersea volcano, but they needed proof. The volcano was mostly ignored after 1952. It was often wrongly labeled as an "older volcanic feature" on maps. In 1955, geologist Kenneth O. Emery named the seamount "Kamaʻehuakanaloa" because of its long and narrow shape.

In 1978, an expedition studied strong, repeated earthquake activity around Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Instead of an old, extinct seamount, they found that Kamaʻehuakanaloa was a young, possibly active volcano. They saw that it was covered with both new and old lava flows. They also found hot fluids coming out of active hydrothermal vents.

In 1978, a US Geological Survey research ship collected rock samples and took pictures of Kamaʻehuakanaloa's summit. They wanted to see if it was active. Analyzing the photos and testing the pillow lava samples showed that the material was "fresh." This gave more proof that Kamaʻehuakanaloa is still active. More samples and photos were collected from 1980 to 1981, confirming this. Studies showed that eruptions came from the southern part of the volcano's rift crater. This area is closest to the Hawaiʻi hotspot, which feeds magma to Kamaʻehuakanaloa.

After a seismic event in 1986, five special ocean bottom observatories (OBOs) were placed on Kamaʻehuakanaloa for a month. The volcano's frequent earthquakes make it a great place to study seismic activity with OBOs. In 1987, a submersible called DSV Alvin was used to explore Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Another automatic observatory was placed there in 1991 to track earthquake swarms.

From 1996 to Today

Most of what we know about Kamaʻehuakanaloa comes from dives made after the 1996 eruption. During a dive right after the earthquakes, it was hard to see. The water was full of minerals and large floating mats of bacteria. These bacteria feed on dissolved nutrients. They had already started living around the new hot vents at Pele's Pit. They were carefully collected for study.

Scientists used special mapping tools to measure the changes at the summit after the 1996 collapse. Surveys of the hot plumes confirmed changes in the energy and dissolved minerals coming from Kamaʻehuakanaloa. The Pisces V submersible from the Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL) allowed scientists to collect samples of the vent waters, tiny organisms, and mineral deposits.

Since 2006, the Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory (FeMO) has led research trips to Kamaʻehuakanaloa every October. These trips study the many iron-oxidizing bacteria that live there. Kamaʻehuakanaloa's large vent system has a lot of carbon dioxide and iron, but little sulfide. This environment is perfect for iron-oxidizing bacteria, called FeOB, to grow.

HUGO (Hawaii Undersea Geological Observatory)

In 1997, scientists from the University of Hawaiʻi placed an ocean bottom observatory on Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount's summit. This underwater observatory was called HUGO (Hawaiʻi Undersea Geological Observatory). HUGO was connected to the shore, 34 km (21 mi) away, by a fiber optic cable. It was designed to give scientists live data about the volcano. This included seismic, chemical, and visual information. Kamaʻehuakanaloa had become an international lab for studying underwater volcanoes. The cable that powered HUGO broke in April 1998, shutting it down. The observatory was brought back from the seafloor in 2002.

Life Around the Volcano

Hot Vents and Water Chemistry

| Vent Name | Depth | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pele's | 1,000 m (3,281 ft) | Summit | Destroyed in 1996 |

| Kapo's | 1,280 m (4,199 ft) | Upper South rift | No longer releasing hot water |

| Forbidden | 1,160 m (3,806 ft) | Pele's Pit | Over 200 °C (392 °F) |

| Lohiau ("slow") | 1,173 m (3,850 ft) | Pele's Pit | 77 °C (171 °F) |

| Pahaku ("rocky") | 1,196 m (3,924 ft) | South rift zone | 17 °C (63 °F) |

| Ula ("red") | 1,099 m (3,606 ft) | South summit | Spreading out hot water |

| Maximilian | 1,249 m (4,098 ft) | West summit side | Spreading out hot water |

| Naha | 1,325 m (4,347 ft) | South rift | 23 °C (73 °F) |

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Its steady system of hot vents creates a rich home for a community of tiny living things. There are many hydrothermal vents on Kamaʻehuakanaloa's crater floor, its north slope, and along its summit.

Active hot vents were first found at Kamaʻehuakanaloa in the late 1980s. These vents are very similar to those found at the mid-ocean ridges. They have similar water makeup and temperatures. The two main vent areas are at the summit: Pele's Pit (formerly Pele's Vents) and Kapo's Vents. They are named after the Hawaiian deity Pele and her sister Kapo. These were once "low temperature vents" with water around 30 °C (86 °F). But the 1996 volcanic eruption and the creation of Pele's Pit changed this. It started high-temperature venting, with water reaching 77 °C (171 °F) in 1996.

Microorganisms Living Near the Vents

The vents are 1,100 to 1,325 m (3,609 to 4,347 ft) below the surface. Their temperatures range from 10 to over 200 °C (392 °F). The water from the vents has a lot of CO2 (carbon dioxide) and Fe (Iron), but not much sulfide. Low oxygen and pH levels help support the high amounts of iron. These conditions are perfect for iron-oxidizing bacteria, called FeOB, to grow. One example is Mariprofundus ferrooxydans. The materials from the vents are similar to those from black smokers, which are home to archaea extremophiles.

Many different microbial mats surround the vents and cover Pele's Pit. The Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL) studies these hot systems and the tiny living things there. In 1999, the NSF funded a trip to collect extremophiles from Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Microbial mats surrounded the 160 °C (320 °F) vents. They even found a new jelly-like organism. Samples were collected for study. In 2001, the Pisces V submersible collected more organisms to bring to the surface.

Larger Animals Around the Volcano

The marine life around Kamaʻehuakanaloa is not as varied as in other, less active seamounts. Fish found near Kamaʻehuakanaloa include the Celebes monkfish (Sladenia remiger) and members of the Cutthroat eel family. Invertebrates (animals without backbones) found here include two species that live only near these hot vents. These are a bresiliid shrimp (Opaepele loihi) and a tube or pogonophoran worm. After the 1996 earthquake swarms, scientists couldn't find either the shrimp or the worm. It's not known if the quakes had a lasting effect on these species.

From 1982 to 1992, researchers used Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory submersibles to photograph fish at Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount and other locations. A few fish species seen at Kamaʻehuakanaloa were new sightings for Hawaii. These included the Tassled coffinfish (Chaunax fimbriatus) and the Celebes monkfish.

See also

In Spanish: Lōʻihi para niños

In Spanish: Lōʻihi para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |