Kīlauea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kīlauea |

|

|---|---|

Kīlauea erupting at Halemaʻumaʻu, a pit crater within its summit caldera, on January 16, 2025.

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,247 m (4,091 ft) |

| Prominence | 15.3 m (50 ft) |

| Geography | |

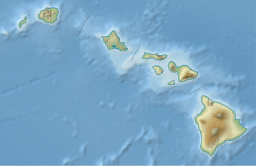

| Location | Hawaiʻi, United States |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 210,000 to 280,000 years old |

| Mountain type | Shield volcano, hotspot volcano |

| Last eruption | Since December 23, 2024 (ongoing) |

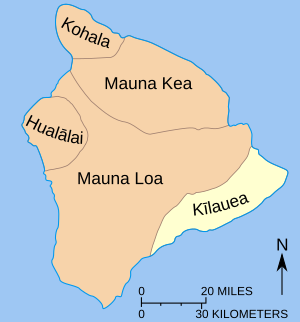

Kīlauea (pronounced KIL-uh-WAY-uh) is a very active volcano in the Hawaiian Islands. It sits on the southeastern coast of Hawaii Island. This volcano is quite old, between 210,000 and 280,000 years old. It rose above the ocean about 100,000 years ago. Kīlauea is the most active of the five volcanoes that make up Hawaii Island. It is also one of the most active volcanoes on Earth! Its most recent eruption started in December 2024. This eruption has continued into 2025, with lava fountains and flows.

Kīlauea is the second youngest volcano formed by the Hawaiian hotspot. This is a special place deep in the Earth where hot rock rises. It is part of a long chain of underwater mountains called the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain. For a long time, people thought Kīlauea was just a part of its bigger neighbor, Mauna Loa. This was because Kīlauea doesn't stand out much on its own. Also, their eruptions often happened at different times. Kīlauea has a big bowl-shaped crater at its top, called a caldera. It also has two active areas where lava often breaks through, called rift zones. One rift zone stretches 125 kilometers (78 miles) to the east. The other goes 35 kilometers (22 miles) to the west. There's also a moving crack in the ground, called a fault, that shifts a little each year.

From 2008 to 2018, a crater called Halemaʻumaʻu at Kīlauea's summit had a bubbling lake of lava. Kīlauea also erupted almost non-stop from 1983 to 2018 from its eastern rift zone. This long eruption caused a lot of damage. It destroyed towns like Kalapana and Kaimū in 1990. It also covered a famous black sand beach.

In May 2018, the eruption moved to the lower Puna area. Lava burst from many cracks in the ground. It flowed like rivers into the ocean in three spots. This eruption destroyed Hawaii's biggest natural freshwater lake, Green Lake. It also covered parts of Leilani Estates and Lanipuna Gardens. Towns like Kapoho were also destroyed. Over 700 homes were lost. At the same time, the lava lake at Halemaʻumaʻu disappeared. The volcano's summit began to collapse with loud explosions. One blast sent ash 9,100 meters (30,000 feet) into the sky. This led to the closure of parts of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. The eruption finished in September 2018. Since 2020, Kīlauea has erupted several times. These eruptions happened in the larger Halemaʻumaʻu crater and along the volcano's rift zones.

Contents

- Understanding Kīlauea's History

- How Kīlauea Was Formed

- Kīlauea's Eruptions Over Time

- Volcano Hazards and Safety

- Kīlauea's Natural Environment

- People and Kīlauea

- Research and Discoveries

- Visiting Kīlauea

- See also

Understanding Kīlauea's History

Kīlauea means "spewing" or "much spreading" in the Hawaiian language. This name describes how often it pours out lava. The oldest lava from Kīlauea formed when the volcano was still underwater. Scientists have found these ancient lava samples using special underwater robots. Most of the volcano's surface is covered by lava less than 1,000 years old. The very oldest lava we can see is about 2,800 years old.

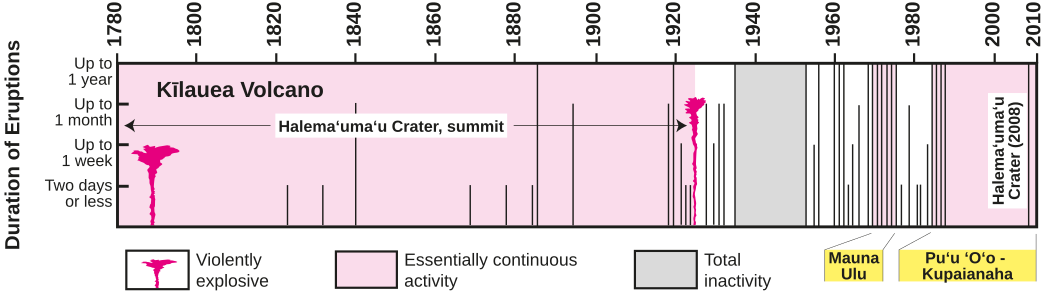

Scientists use special methods to figure out when eruptions happened. They found a big eruption around 1410. This was the first one mentioned in the stories passed down by Native Hawaiians. Written records about Kīlauea started in 1778. The first eruption recorded by Westerners was in 1823. After that, Kīlauea erupted many times. Most eruptions happened at the top of the volcano or along its eastern rift zone. These eruptions often lasted a long time and involved lava flowing out smoothly. Before written history, powerful explosive eruptions were common. In 1790, one such eruption killed over 400 people. This makes it the deadliest volcanic eruption in what is now the United States.

The eruption from 1983 to 2018 was Kīlauea's longest in modern times. It was also one of the longest eruptions ever recorded on Earth. This eruption produced a huge amount of lava, about 3.5 cubic kilometers (0.84 cubic miles). It covered 123.2 square kilometers (47.6 square miles) of land. Centuries before this, a much larger eruption, the ʻAilāʻau eruption, lasted about 60 years. It ended around 1470.

Kīlauea's activity greatly affects the plants and animals on its slopes. Lava flows and ash can destroy forests. Volcanic gases like sulfur dioxide create acid rain. This makes some areas, like the Kaʻū Desert, barren. However, many unique animals and plants thrive in other parts of the volcano. This is because Hawaii Island is very isolated. In Hawaiian mythology, the volcanoes were sacred. Halemaʻumaʻu was believed to be the home of Pele, the goddess of fire and volcanoes.

An English missionary named William Ellis gave the first modern description of Kīlauea in 1823. He spent two weeks exploring the volcano. The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory was founded in 1912 by Thomas Jaggar. It is the main place for studying Kīlauea and other volcanoes on the island. In 1916, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park was created. It is a World Heritage Site and a popular place for tourists.

How Kīlauea Was Formed

Volcano's Location and Origin

Like all Hawaiian volcanoes, Kīlauea formed as the Pacific tectonic plate moved over the Hawaiian hotspot. This hotspot is a very hot spot in the Earth's deep mantle. This process has created a chain of mountains and volcanoes over 70 million years. This chain is 6,000 kilometers (3,700 miles) long. Scientists believe the hotspot has stayed in mostly the same place for a very long time.

Kīlauea is one of five volcanoes on Hawaii Island that rose from under the sea. The oldest volcano on the island, Kohala, is over a million years old. Kīlauea is the youngest, between 300,000 and 600,000 years old. Another younger volcano, Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount, is still underwater. Kīlauea is the second youngest volcano in the long Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain.

Kīlauea began as an underwater volcano. It grew bigger and taller through eruptions of lava under the sea. It finally broke the ocean surface with explosive eruptions about 50,000 to 100,000 years ago. Since then, the volcano has had many eruptions. These eruptions have been both smooth lava flows and explosive blasts.

Kīlauea's Structure and Features

Kīlauea has been active throughout its history. You can see many features from its past eruptions. These include small cone-shaped hills, lava tubes, and other structures. Kīlauea had its longest quiet period between 1934 and 1952, lasting 18 years. Most of Kīlauea is made of hardened lava flows. It also has layers of ash from smaller explosive eruptions. About 90 percent of its surface is covered by lava from the last 1,100 years. Much of the volcano is still underwater. The part above water is a gently sloping shield shape. It covers about 1,500 square kilometers (580 square miles). This is about 13.7 percent of Hawaii Island's total area.

Kīlauea doesn't look like a tall, pointy mountain. It appears as a bulge on the side of Mauna Loa. Early Hawaiians and geologists thought it was just a part of Mauna Loa. However, studies of the lava show they have separate underground magma chambers. But when one volcano is very active, the other tends to be quiet. For example, when Kīlauea was quiet from 1934 to 1952, Mauna Loa was active. This isn't always true, though. Sometimes both volcanoes erupt at the same time. This suggests they might be connected deep underground.

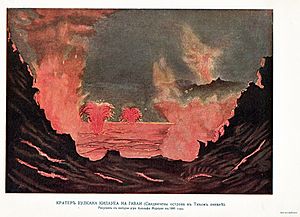

Kaluapele: The Summit Crater

Kīlauea has a large crater at its summit called Kaluapele. This name means "the pit of Pele." It is about 4 by 3.2 kilometers (2.5 by 2 miles) wide. Its walls are up to 120 meters (390 feet) high. Lava flows have broken through its southwestern side. We don't know exactly how old Kaluapele is. It might have formed and disappeared many times. Its current shape likely formed around 1470–1510 after a very powerful eruption. A key feature inside Kaluapele is Halemaʻumaʻu. This is a large pit crater and a very active eruption spot. It is about 920 meters (3,000 feet) wide and 85 meters (280 feet) deep. Its shape has changed a lot over time.

Rift Zones: Where Lava Breaks Through

Kīlauea has two rift zones that spread out from its summit. These are areas where the volcano's surface is cracking. One rift zone goes 125 kilometers (78 miles) to the east. The other is 35 kilometers (22 miles) long and goes southwest. These rift zones are connected by a series of cracks called the Koaʻe Fault Zone. The volcano is slowly sliding towards the sea along these zones. This happens at a rate of about 6 to 10 centimeters (2 to 4 inches) per year.

The eastern rift zone is a very important part of the volcano. Almost all of it is covered in lava from the last 400 years. Its upper part is 2 to 4 kilometers (1 to 2 miles) wide. This area has many large pit craters. It extends deep underwater, more than 5,000 meters (16,400 feet). The southwestern rift zone is much smaller and less active. Its last major eruption was in 1974. It doesn't have as many clear ridges or pit craters.

Hilina Fault System: A Moving Crack

On Kīlauea's southern side, there's a big crack in the ground called the Hilina fault system. This fault is active and moves vertically. It shifts about 2 to 20 millimeters (0.08 to 0.8 inches) each year. This area is 500 meters (1,600 feet) deep. Scientists are still studying how deep this fault goes into the Earth.

Kīlauea's Eruptions Over Time

All of Kīlauea's recorded eruptions have happened at Kaluapele (the summit crater), the eastern rift zone, or the southwestern rift zone. About half of its eruptions have been at or near Kaluapele. Activity there was almost constant for much of the 1800s. It ended around 1934 after a big explosive eruption in 1924. Later, most activity moved to the eastern rift zone. This area has had 24 recorded eruptions. The southwestern rift zone has been much quieter, with only five events.

Ancient Eruptions and Stories

Geologists have studied and recorded many major eruptions throughout Kīlauea's long history. The oldest lava flows, from 275,000 to 225,000 years ago, were found deep underwater. These lavas show how the volcano erupted when it was still a rising mountain under the sea. Scientists also drill into the ground to get core samples of older lava. The oldest reliably dated rock is 43,000 years old. It was found under a layer of ash.

The oldest well-studied ash from Kīlauea is called the Uwēkahuna Ash Member. It came from explosive eruptions between 800 and 100 BC. This ash spread over 20 kilometers (12 miles) from Kaluapele. This shows how powerful those eruptions were. Around 1,200 years ago, lava from an older crater filled and solidified its structure. After that, lava flowed smoothly from the summit through underground tubes.

The ʻAilāʻau Eruption and Pele's Legend

The longest major eruption seen by Native Hawaiians happened from about 1410 to 1470. This eruption, called the ʻAilāʻau eruption, lasted about 60 years. Its lava flows covered most of Kīlauea's northern side in the Puna District. Because of this long eruption, the summit of the volcano collapsed around 1470–1510. This created the Kaluapele crater we see today.

These events are also told in the ancient Hawaiian stories about the goddess Pele. According to the myths, Pele made Kīlauea her home. She sent her sister Hiʻiaka to find a man named Lohiʻau. Pele promised to protect the Puna forests if Hiʻiaka returned in 40 days. But Hiʻiaka took longer, and Pele burned the forest. When Hiʻiaka returned, she was angry. Pele then killed Lohiʻau and threw him into a pit at Kīlauea's summit. Hiʻiaka dug furiously to get his body back, sending rocks flying everywhere. Scientists believe these stories describe the ʻAilāʻau lava flow and the collapse of Kaluapele.

After this, Kīlauea had 300 years of explosive eruptions. This was from about 1510 to 1790. These eruptions created the Keanakākoʻi Tephra. Lava shot hundreds of meters into the sky, spreading ash across the land.

Eruptions from 1790 to 1934

The first reliable written records of Kīlauea are from around 1820. The first eruption well-documented by Westerners was in 1823. A powerful eruption in 1790 killed over 400 warriors. Their footprints are still preserved in Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park. Kīlauea has erupted 61 times between 1823 and 2024. This makes it one of the most active volcanoes on Earth.

The amount of lava Kīlauea released varied greatly. Kaluapele slowly filled up with lava from 1823 to 1840. About 3 cubic kilometers (0.7 cubic miles) of lava were released. From 1840 to 1920, about half that amount of lava came out. The volcano was unusually quiet from 1920 to 1950. After that, Kīlauea's eruptions became more frequent again.

Eruptions lasted from days to years and happened in different places. Activity at Kaluapele was almost continuous for much of the 1800s. It continued until 1924, after a break from 1894 to 1907. Before Europeans arrived, Kīlauea often had explosive eruptions. This is known from tribal chants.

A major eruption happened in 1840. Lava flowed smoothly for 35 kilometers (22 miles) along the eastern rift zone. This was a very long flow for a rift eruption. It lasted 26 days and produced a huge amount of lava. The light from the eruption was so bright that people could read newspapers 30 kilometers (19 miles) away in Hilo at night.

The volcano was active again in 1868, 1877, 1884, 1885, 1894, and 1918. Its next big eruption was in 1918–1919. Halemaʻumaʻu, which was a small pool of lava then, had a lava lake that drained and refilled. This lake almost reached the top of Kaluapele. This activity eventually led to the creation of Mauna Iki. This lava shield formed on the volcano's southwest rift zone over eight months. This eruption included lava fountains and activity along the rift zone.

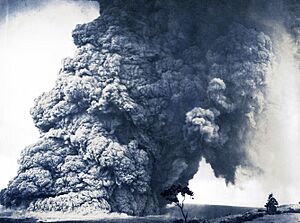

More activity followed from 1921–1923. The next major eruption was in 1924. Halemaʻumaʻu first drained, then quickly sank. It became nearly 210 meters (690 feet) deep under a thick cloud of ash. Explosive activity began on May 10. It blew out rocks weighing up to 45 kilograms (99 pounds) as far as 60 meters (200 feet). Smaller pieces weighing about 9 kilograms (20 pounds) flew 270 meters (890 feet). The eruption became more intense on May 18. A huge explosion caused the only death of that eruption. The eruption continued, forming ash columns over 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) high. It ended by May 28. Volcanic activity then stayed at the summit and stopped after 1934. From 1823 to 1924, the volcano erupted 15 times. There were also 11 times when the summit sank.

Eruptions from 1952 to 1982

After the Halemaʻumaʻu event, Kīlauea was relatively quiet. For a while, all activity was at the summit. The volcano became active again in 1952. A lava fountain shot 245 meters (800 feet) high at Halemaʻumaʻu. Several lava fountains, 15 to 30 meters (49 to 98 feet) high, continued. This eruption lasted 136 days. Eruptions also happened in 1954, 1955, and 1959. A big event in 1960 involved steam explosions and earthquakes. This led to a massive lava flow that covered towns and resorts. The summit then collapsed even further.

After 1960, eruptions happened often until August 2018. From 1967–1968, a very large eruption lasted 251 days. It produced 80 million cubic meters of lava from Halemaʻumaʻu. In 1969, the long Mauna Ulu eruption began. It lasted from May 24, 1969, to July 24, 1974. This eruption added 230 acres (93 hectares) of land to the island. A strong earthquake then caused a partial summit collapse. Activity paused until 1977. Mauna Ulu was the longest flank eruption ever recorded for a Hawaiian volcano at that time. It created a new vent and covered a large area with lava. Lava fountains shot as high as 540 meters (1,772 feet) into the air.

The Long Eruption: 1983–2018

Another eruption occurred from January 1983 to September 2018. This was the longest eruption ever observed at Kīlauea. It was also the twelfth-longest volcanic eruption on Earth since 1750. The eruption began on January 3, 1983, along the eastern rift zone. Lava fountains quickly built up a cone called Puʻu ʻŌʻō. Lava flows then moved down the slopes.

In 1986, the activity moved to a new vent called Kūpaʻianahā. Here, the lava flowed out more smoothly. Kūpaʻianahā built a wide, low shield volcano. Lava tubes carried flows 11 to 12 kilometers (7 to 7.5 miles) to the sea. From 1986 to 1991, several towns and communities were destroyed by lava. These included Kalapana and Kaimū, and a black sand beach was covered. In 1992, the eruption moved back to Puʻu ʻŌʻō. It continued in the same way, covering old lava flows and large parts of the coastline.

By the end of 2016, this eastern rift zone eruption had produced 4.4 cubic kilometers (1.1 cubic miles) of lava. It covered 144 square kilometers (56 square miles) of land. It also added 179 hectares (440 acres) of new land to the island. This eruption destroyed 215 buildings. It buried 14.3 kilometers (8.9 miles) of highway under lava up to 35 meters (110 feet) thick.

Besides the constant activity at Puʻu ʻŌʻō, a separate eruption began at Kīlauea's summit in March 2008. On March 19, 2008, a new vent opened at Halemaʻumaʻu. This followed months of increased sulfur dioxide gas and earthquakes. A new crater formed, informally called the "Overlook Crater." It released a thick gas plume. Explosive events happened at this vent throughout 2008.

On September 5, 2008, scientists saw a lava pond deep inside the Overlook Crater for the first time. From February 2010 to May 2018, a lava pond was almost always visible. Lava briefly overflowed the vent onto the floor of Halemaʻumaʻu several times. This happened in April and May 2015, October 2016, and April 2018.

The 2018 Eruptions

In March 2018, scientists noticed that Puʻu ʻŌʻō was rapidly swelling. They warned that this increased pressure could create a new vent. On April 30, 2018, the crater floor of Puʻu ʻŌʻō collapsed. Magma moved underground into the lower Puna region. Over the next few days, hundreds of small earthquakes happened. Officials issued evacuation warnings. On May 3, 2018, new cracks opened, and lava began erupting in lower Puna. This happened after a magnitude 5.0 earthquake earlier that day. People in Leilani Estates and Lanipuna Gardens had to evacuate.

A related magnitude 6.9 earthquake happened on May 4. By May 9, 27 houses in Leilani Estates were destroyed.

By May 21, two lava flows had reached the Pacific Ocean. They created thick clouds of "laze." Laze is a toxic mix of lava and haze. It contains hydrochloric acid and tiny glass particles.

By May 31, lava had destroyed 87 houses in Leilani Estates. More evacuation orders were given, including for the town of Kapoho. By June 4, lava had flowed through Kapoho and into the ocean. The number of lost houses reached 159, then 533, and finally 657.

The lava lake at Halemaʻumaʻu began to drop on May 2. Scientists warned that this could lead to steam explosions. These explosions happen when magma interacts with underground water. Similar explosions happened in 1924. These concerns led to the closure of Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park. On May 17, an explosive eruption happened at Halemaʻumaʻu. It created an ash plume 9,100 meters (30,000 feet) high. This started a series of strong explosions. They produced large ash plumes from Halemaʻumaʻu. These explosions, along with big earthquakes and collapses, continued until early August.

Water Lake and Recent Eruptions (2019-2025)

In late July 2019, a water lake appeared at the bottom of Halemaʻumaʻu. This was the first time in over 200 years. Water from the rising water table began to fill the crater. The lake slowly grew in size. By December 1, 2020, it was about 49 meters (160 feet) deep. The water's surface temperature was usually between 70–85 degrees Celsius (158–185 degrees Fahrenheit). Within a month, a new eruption replaced the water lake with a lava lake.

On December 20, 2020, an eruption began inside Halemaʻumaʻu. Three vents fed lava into the crater. This boiled away the water lake and replaced it with lava. The eruption sent a plume 9,100 meters (30,000 feet) into the air. Earthquakes had happened before the eruption. By the next morning, the eruption was stable. Two vents remained active, filling the crater floor with lava. By December 25, 2020, the lava lake was 176 meters (577 feet) deep. By February 24, 2021, it was 216 meters (709 feet) deep. A cone of hardened lava had formed around the western vent.

The eruption continued for a few more months, but with less activity. By May 26, 2021, it had stopped erupting. The lava supply seemed to have ended between May 11 and May 13. The lake's surface had hardened by May 20. The last surface activity was seen on May 23. When the eruption stopped, the lava lake was 229 meters (751 feet) deep.

On August 23, 2021, scientists raised Kīlauea's alert status. This was due to many earthquakes and ground changes at the summit. They lowered the alert status two days later.

September 2021 Summit Eruption

Scientists noticed more earthquakes and ground changes at Kīlauea's summit on September 29, 2021. An eruption began at 3:20 p.m. local time. Several cracks opened within Halemaʻumaʻu crater. At first, lava fountains shot over 60 meters (200 feet) high. As the lava level in the crater rose, the fountains became shorter.

Lava continued to erupt at Halemaʻumaʻu throughout the fall. By October 5, 2022, about 111 million cubic meters (29 billion gallons) of lava had flowed out. The floor of Halemaʻumaʻu had risen 143 meters (469 feet). The eruption paused on December 9, 2022. The alert level was lowered, but earthquake activity was still present.

2023 Summit Eruptions

Eruptions inside Halemaʻumaʻu started again on January 5, 2023. This eruption lasted 61 days, ending on March 7, 2023.

On June 7, 2023, web cameras showed a glow at Kīlauea's summit. This meant a new eruption had begun in the Halemaʻumaʻu crater. This eruption ended after twelve days on June 19, 2023.

The third Halemaʻumaʻu eruption of 2023 happened from September 10 to September 16, 2023. Multiple vents opened during this time.

2024–2025 Rift and Summit Eruptions

Shortly after midnight on June 3, 2024, an eruption happened. It came from several cracks on Kīlauea's upper southwest rift zone. This eruption lasted about 8.5 hours.

A second eruption took place from September 15 to September 20, 2024. It was near and inside Nāpau Crater. This is a remote and uninhabited part of the volcano's middle east rift. The eruption had four phases. The last activity from a small vent ended on September 20.

On December 23, 2024, an eruption began within Halemaʻumaʻu. This eruption has continued into 2025. Lava fountains have reached as high as 180 meters (600 feet) in March. In May, they reached 350 meters (1,150 feet). Also in May, the National Park Service reopened the public viewing area at Uēkahuna. This was the former site of the Hawaii Volcano Observatory and the Jaggar Museum.

Volcano Hazards and Safety

In 2018, the USGS National Volcanic Threat Assessment rated Kīlauea as having a high threat score. It was ranked as the most likely volcano in the United States to threaten people and buildings.

Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI)

The Global Volcanism Program uses a scale called the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI). This scale measures how explosive an eruption is. A higher number means a more explosive eruption. Kīlauea has had 96 known eruptions in the last 11,700 years. A VEI was given to 90 of them. The 1790 eruption received a VEI of 4, which is very powerful. The 1983–2018 eruption was a 3. The eruptions of 1820, 1924, 1959, and 1960 were rated 2. Other eruptions received a 1 or 0.

| VEI | Number of Holocene eruptions for which a VEI has been assigned (total=91) |

|---|---|

| VEI 0 |

75

|

| VEI 1 |

10

|

| VEI 2 |

4

|

| VEI 3 |

1

|

| VEI 4 |

1

|

Ancient Stories as Guides

Native Hawaiians have passed down stories about the volcanoes for generations. These ancient stories offer important cultural and geological knowledge. In volcanology, using oral history has become a valuable way to understand a region's eruption past. These stories can help confirm scientific data. They can also help assess dangers during an eruption. They even guide communities in recovering after an event.

By studying the oral history of the ʻAilāʻau eruption, scientists learned that Kīlauea was much more explosive than they first thought. Based on its past, these traditions suggest that Kīlauea could have long periods of explosive eruptions. Hawaiian chants also hinted that surface water was once found at the summit. The story of Pele and Hiʻiaka describes large lava flows and the collapse of Kaluapele around 1500.

Kīlauea's Natural Environment

Ecology and Unique Wildlife

Hawaii Island is over 3,000 kilometers (1,900 miles) from the nearest land. This makes it one of the most isolated places on Earth. This isolation has greatly shaped its ecology. Most of the plants and animals on the island are endemic. This means they are found nowhere else in the world. However, this unique ecosystem is easily harmed by invasive species and human development. About one-third of the island's native plants and animals are now extinct.

Kīlauea's natural community is also threatened by the volcano itself. Lava flows often burn and cover forests. Ash can smother local plant life. Layers of burnt plant material under ash show this destruction. Some parts of the volcano's slopes show a clear difference. You can see untouched mountain forests next to volcanic "deserts" that have not yet regrown plants.

Kīlauea's size also affects the local climate. Winds from the northeast are pushed upwards by the volcano. This creates a wet side (windward) and a dry side (leeward). The volcano's environment changes with its height and the types of volcanic soil. The northern part of Kīlauea is mostly below 1,000 meters (3,300 feet). It gets a lot of rain, over 190 centimeters (75 inches) each year. This area is mostly a wet lowland forest. Farther south, with less rain, it is a drier lowland area.

Diverse Ecosystems and Animal Life

Much of Kīlauea's southern part is inside the national park. Here, you can find aʻe ferns, ʻōhiʻa trees (Metrosideros polymorpha), and hapuʻu ferns (Cibotium). The park is home to many bird species. These include the ʻapapane (Himatione sanguinea), ʻamakihi (Hemignathus virens), and iʻiwi (Vestiaria coccinea). Some endangered birds also live here, like the ʻakepa (Loxops coccineus) and nēnē (Branta sandvicensis). The coast has three of the island's nine known nesting sites for the critically endangered hawksbill sea turtle.

Some areas along the southwestern rift zone are called the Kaʻū Desert. It's not a true desert, as it gets over 1,000 millimeters (39 inches) of rain a year. But the rain mixes with volcanic sulfur dioxide. This creates acid rain with a very low pH, sometimes as low as 3.4. This acid rain greatly stops plants from growing. The volcanic ash also makes the soil very porous. Because of this, plant life is almost nonexistent there.

Kīlauea's northern wet forest is partly protected by the Puna Forest Reserve. This reserve is 27,785 acres (11,244 hectares). It is Hawaii's largest lowland wet forest. It is home to rare plants like hāpuʻu ferns and ʻieʻie vines. These plants help control invasive species. Animals like the ʻōpeʻapeʻa (Hawaiian hoary bat) and ʻio (Hawaiian hawk) live in the trees. Many more unknown species are thought to live in this forest. The main tree in Wao Kele is the ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha).

People and Kīlauea

Ancient Hawaiian Life and Beliefs

The first Ancient Hawaiians settled along the shores of Hawaii Island. Food and water were easy to find there. Birds that had no natural enemies became a main food source. Early settlements greatly changed the local environment. Many species, especially birds, became extinct. New plants and animals were brought in, and erosion increased. The lowland forests turned into grasslands. This was partly due to fires, but mostly because of the Polynesian rat.

The tops of the island's volcanoes are considered sacred. In Hawaiian mythology, the sky father Wākea and earth mother Papa gave birth to the islands. Kīlauea itself is believed to be the body of the goddess Pele. She is the goddess of fire, lightning, wind, and volcanoes. The story of Pele and the rain god Kamapuaʻa is centered here. Halemaʻumaʻu, meaning "House of the ʻamaʻumaʻu fern," gets its name from their struggle. Kamapuaʻa, bothered by Pele's lava, covered her favorite home with fern fronds. Pele, choked by smoke, emerged. The gods then decided to divide the island. Kamapuaʻa got the wet northeast side, and Pele got the drier Kona side. The reddish look of young ʻamaʻumaʻu fern fronds is said to come from this legendary fight.

Modern Exploration and Study

The first foreigner to arrive in Hawaii was James Cook in 1778. The first non-native to study Kīlauea closely was William Ellis. He was an English missionary who explored the volcano for over two weeks in 1823. He wrote the first detailed account of the volcano.

Another missionary, C. S. Stewart, also wrote about Kīlauea in his journal. His writings were even quoted in a poem about the volcano.

James Dwight Dana was one of the earliest and most important geologists to study Kīlauea. He visited the summit in 1840. He studied and wrote about the island's volcanoes for decades. At first, he thought Kīlauea was just part of Mauna Loa. But later research by geologist C. E. Dutton helped show that Kīlauea is its own separate volcano.

Hawaiian Volcano Observatory: Watching the Volcano

The next important time in Kīlauea's history began with the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) in 1912. This was the first permanent volcano observatory in the United States. It was the idea of Thomas Jaggar, a geology professor. After seeing a terrible earthquake in Italy, he believed that volcanoes and earthquakes needed to be studied carefully. He chose Kīlauea as the first place to do this.

Jaggar led the observatory from 1912 to 1940. He started new ways of studying the volcano using seismographs and observations. The HVO was funded by different groups over the years. The USGS took over funding after 1946. The main building of the observatory moved twice. The facility on the rim of Kaluapele was damaged by volcanic activity in 2018. The buildings were taken down in 2024.

NASA used the area around Kīlauea to train Apollo Astronauts. They learned to recognize volcanic features, plan routes, collect samples, and take photos. This training helped astronauts from Apollo 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17 on the Moon.

Research and Discoveries

In 2019 and 2020, volcanologists used drones to study gases inside the water lake at the summit. It was too dangerous for people to get close. After the lake boiled away, they used drones to study the gas plumes.

In 2022, researchers found that Kīlauea's seismic waves could help predict future eruptions. These waves can last for many seconds. Scientists studied thousands of events from sensors and GPS stations. They looked at things like temperature and gas bubbles. They found that magma temperature was linked to how long seismic signals lasted and the amount of bubbles.

Visiting Kīlauea

Kīlauea became a popular place for tourists in the 1840s. Businessmen built hotels on the rim of the volcano. One of these, Volcano House, is the only hotel inside Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park.

In 1891, Lorrin A. Thurston, who invested in hotels, started a campaign for a national park. This idea was first suggested in 1903. Thurston used his newspaper to support the idea. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed a bill to create "Hawaii National Park." It was the country's 11th National Park.

The park was later renamed Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park. It is now a major place for conservation and tourism. Since 1987, it has been a World Heritage Site. Tourism to Hawaii grew rapidly after jet airplanes became common around 1959. Kīlauea, as one of the few volcanoes that erupts often, became a big draw. About 2.6 million people visit Kīlauea every year.

The Thomas A. Jaggar Museum was a popular tourist spot. It was located at the edge of Kaluapele. Its observation deck offered the best view of Halemaʻumaʻu. However, the museum closed permanently after the 2018 earthquakes damaged the building.

Volcano House offers places to stay inside the park. More lodging options are available in the nearby Volcano Village. The Kilauea Military Camp provides housing for military visitors. The park has hiking trails, interesting sights, and guided ranger programs. The Crater Rim Trail around the volcano is a special National Recreation Trail.

See also

In Spanish: Kīlauea para niños

In Spanish: Kīlauea para niños