Kwakwakaʼwakw facts for kids

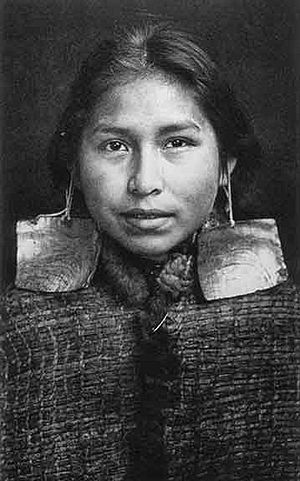

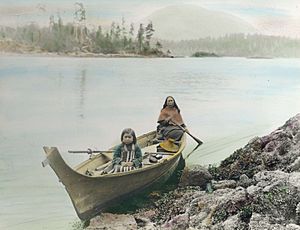

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw mask (19th century)

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,665 (2016 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (British Columbia) | |

| Languages | |

| English, Kwakʼwala | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Traditional Indigenous religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Haisla, Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv |

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw (pronounced kʷakʷəkʲəʔwakʷ) are one of the many indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. They are also sometimes called the Kwakiutl (pronounced KWAH-kyoo-tul). This name means "Kwakʼwala-speaking peoples."

In 2016, about 3,665 Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people were counted. Most of them live in their traditional lands. These lands are on northern Vancouver Island, nearby small islands like the Discovery Islands, and the coast of British Columbia. Some Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw also live in cities like Victoria and Vancouver. They are organized into 13 different groups called band governments. These bands help manage their communities.

Their language is called Kwakʼwala. Sadly, only about 3.1% of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people speak it today. The language has four main dialects: Kwak̓wala, ʼNak̓wala, G̱uc̓ala, and T̓łat̓łasik̓wala.

Contents

Understanding the Name Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw

The name Kwakiutl comes from Kwaguʼł. This is the name of just one Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw community in Fort Rupert. An expert named Franz Boas did most of his studies there. He made the name Kwakiutl popular for both this community and all the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people.

However, this name was often used incorrectly. It was used for all nations who spoke Kwakʼwala. It was also used for three other Indigenous groups whose languages are part of the Wakashan family, but are not Kwakʼwala. These groups, sometimes wrongly called the Northern Kwakiutl, are the Haisla, Wuikinuxv, and Heiltsuk.

Many people who are called "Kwakiutl" feel this name is wrong. They prefer the name Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw. This name means "Kwakʼwala-speaking-peoples." One group that is an exception is the Laich-kwil-tach in Campbell River. They are known as the Southern Kwakiutl. Their council is called the Kwakiutl District Council.

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw History and Origins

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw have many oral stories about their past. These stories say their ancestors (called ʼnaʼmima) came to their lands in animal forms. These animals arrived by land, sea, or from underground. When an animal ancestor reached a certain place, it changed its animal shape and became human.

Some of these ancestral animals include the Thunderbird, his brother Kolas, the seagull, orca, grizzly bear, or a chief ghost. Some ancestors were human and came from far-off places.

Life Before European Contact

Historically, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw mainly fished for food. Men also hunted some animals, and women gathered wild fruits and berries. They were skilled at weaving and carving wood. These crafts were very important.

Wealth was shown off and traded at special ceremonies called potlatches. Wealth included things like slaves and valuable goods. An expert named Franz Boas studied these customs a lot. Unlike many other societies, wealth and status were not about how much you owned. Instead, they were about how much you could give away. Giving away your wealth was a main part of a potlatch.

Contact with Europeans and Changes

The first recorded meeting with Europeans was with Captain George Vancouver in 1792. Sadly, diseases brought by European settlers greatly reduced the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw population. This happened in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw population dropped by 75% between 1830 and 1880. The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic alone killed more than half of the people.

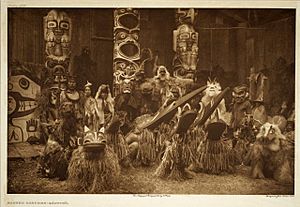

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw dancers from Vancouver Island performed at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Efforts to Revive Culture

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are working hard to bring back their customs, beliefs, and language. They want to restore their connection to their land and rights. Potlatches are happening more often as families reconnect with their traditions. The community uses language programs, classes, and social events to bring back their language. Artists like Mungo Martin, Ellen Neel, and Willie Seaweed worked in the 19th and 20th centuries to revive Kwakwakaʼwakw art and culture.

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Nations and Communities

Each Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw nation has its own clans, chiefs, history, and culture. But they are all similar to the other Kwak̓wala-speaking nations.

| Nation name | IPA | Translation | Community | Anglicized, archaic variants or adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwaguʼł | Smoke-Of-The-World | Tsax̱is / Fort Rupert | Kwagyewlth, Kwakiutl | |

| Mamaliliḵa̱la | The-People-Of-Malilikala | ʼMimkumlis / Village Island | ||

| ʼNa̱mg̱is | Those-Who-Are-One-When-They-Come-Together | Xwa̱lkw / Nimpkish River and Yalis / Alert Bay, | Nimpkish-Cheslakees | |

| Ławitsis | Angry-ones | Ḵalug̱wis / Turnour Island | Tlowitsis | |

| A̱ʼwa̱ʼetła̱la | Those-Up-The-Inlet | Dzawadi / Knight Inlet | ||

| Da̱ʼnaxdaʼx̱w | The-Sandstone-Ones | New Vancouver, Harbledown Island | Tanakteuk | |

| Maʼa̱mtagila | Itsika̱n | Etsekin, Iʼtsika̱n | ||

| Dzawa̱da̱ʼenux̱w | People-Of-The-Eulachon-Country | Gwaʼyi / Kingcome Inlet | Tsawataineuk | |

| Ḵwiḵwa̱sut̓inux̱w | People-Of-The-Other-Side | G̱waʼyasda̱ms / Gilford Island | Kwicksutaineuk | |

| Gwawa̱ʼenux̱w | Heg̱a̱mʼs / Hopetown (Watson Island) | Gwawaenuk | ||

| ʼNak̕waxdaʼx̱w | Baʼaʼs / Blunden Harbour, Seymour Inlet, & Deserters Group | Nakoaktok, Nakwoktak | ||

| Gwaʼsa̱la | T̓a̱kus / Smith Inlet, Burnett Bay | Gwasilla, Quawshelah | ||

| G̱usgimukw | People of Guseʼ | Quatsino | Koskimo | |

| Gwat̕sinux̱w | Head-Of-Inlet-People | Winter Harbour | Oyag̱a̱mʼla / Quatsino | |

| T̓łat̕ła̱siḵwa̱la | Those-Of-The-Ocean-Side | X̱wa̱mdasbeʼ / Hope Island | ||

| Wiwēqay̓i | Ceqʷəl̓utən / Cape Mudge | Weiwaikai, Yuculta, Euclataws, Laich-kwil-tach, Lekwiltok, Likʷʼala | ||

| Wiwēkam | ƛam̓atax̌ʷ / Campbell River | Weiwaikum |

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Society and Culture

Family and Community Structure

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw family structure is based on both parents' sides. It has large extended families and strong community ties. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are made up of many different communities or bands. Within these communities, they are organized into extended family units called naʼmima. This means 'of one kind'.

Each naʼmima had special roles and rights. Each community usually had about four naʼmima, but some had more or less. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people trace their family history back to their ancestors. A head chief, who inherited his role, set the roles for the rest of his family. Each family group had several sub-chiefs. They also gained their titles through family inheritance. These chiefs organized their people to use the shared lands that belonged to their family.

Social Classes

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw society had four main classes:

- Nobility: People born into noble families with strong links to ancestors.

- Aristocracy: People who gained status through wealth, resources, or spiritual powers. They showed or shared these at potlatch ceremonies.

- Commoners: Regular members of the community.

- Slaves: People who were captured or bought.

For the nobility, being born into the right family was not enough. A noble person also had to show good behavior throughout their life to keep their high status.

Property and Resources

Like other groups on the Northwest Coast, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw had a strong idea of property. Land for hunting or fishing was passed down through families. From these lands, people gathered and stored valuable goods.

Economy and Trade

The early Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw economy was based on trading and bartering goods. They traded within their own Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw nations. They also traded with nearby Indigenous nations like the Tsimshian, Tlingit, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Coast Salish peoples.

Over time, the potlatch tradition created a need for extra goods. Showing off wealth had important social meanings. When Europeans arrived, wool blankets had become a common form of money. In the potlatch tradition, hosts were expected to give many gifts to all their guests. This practice created a system of loans and interest, using wool blankets as currency.

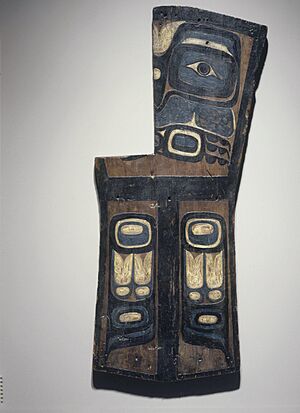

Copper was highly valued by the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, just like by other Pacific Northwest nations. They used it for decorations and valuable items. Before trading with Europeans, some experts think they got copper from natural sources. But this has not been proven. When they met European settlers, especially through the Hudson's Bay Company, more copper came into their lands.

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw also knew about silver and gold. They made detailed bracelets and jewelry from hammered coins they traded from Europeans. Copper had a special value, likely for its use in ceremonies. This copper was flattened into sheets or plates. Then, they painted mythological figures on it. These sheets were used to decorate wooden carvings or kept for their high status.

Some copper pieces even had names based on their value. The value of a piece was set by how many wool blankets it was last traded for. It was seen as a great honor for a buyer to pay more for a copper piece than it was sold for before. This was like their own art market. During a potlatch, copper pieces would be shown. Rival chiefs would offer bids for them. The highest bidder had the honor of buying the copper piece. If a host still had a lot of copper after a big potlatch, he was seen as a very wealthy and important person. High-ranking community members often had the Kwakʼwala word for "copper" in their names.

Copper's importance also led to its use in a Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw shaming ritual. This ceremony involved breaking copper plaques. This act was a challenge. If the person being challenged could not break a plaque of equal or greater value, they were shamed. This ceremony was not performed from the 1950s until 2013. Chief Beau Dick brought it back in 2013 as part of the Idle No More movement. He performed a copper cutting ritual at the British Columbia Legislature on February 10, 2013. This was to ritually shame the government at that time.

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Arts and Traditions

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are a highly organized culture from the Pacific Northwest. They are made up of many separate nations. Each nation has its own history, culture, and way of governing. Nations usually had a head chief who led the nation. Below him were many hereditary family chiefs. In some nations, there were also Eagle Chiefs. This was a separate group within the main society and only applied to potlatching.

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are one of the few cultures where family rights could pass through both the father's and mother's sides. Before colonization, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw society had three classes: nobles, commoners, and slaves. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw shared many cultural and political ties with their neighbors. These included the Nuu-chah-nulth, Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv, and some Coast Salish peoples.

Language Preservation Efforts

The Kwakʼwala language is part of the Wakashan languages group. People started writing down Kwakʼwala words in the 1700s. But a full effort to record the language didn't happen until Franz Boas worked on it in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The use of Kwakʼwala dropped a lot in the 1800s and 1900s. This was mainly because of Canadian government policies that tried to make Indigenous people adopt English ways. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw children were forced to go to residential schools. These schools made them speak English and discouraged their own languages. Even though experts studied Kwakʼwala and Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw culture, these efforts did not stop the language from being lost.

Because of these challenges, there are few Kwakʼwala speakers today. Most remaining speakers are older, which makes it hard to pass the language to children. Like many other Indigenous languages, there are big challenges to bringing it back. Another challenge is that there are four different ways to write the language. Young learners are taught Uʼmista or NAPA, while older generations often use the system developed by Franz Boas.

However, many efforts are underway to bring the language back. In 2005, a plan to build a Kwakwakaʼwakw First Nations Centre for Language Culture gained a lot of support. A review in the 1990s showed that it was still possible to fully revive Kwakʼwala, but serious challenges remained.

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Arts and Crafts

In the past, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw believed that art showed a common link shared by all living things.

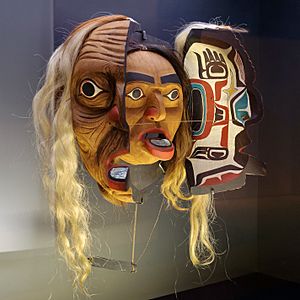

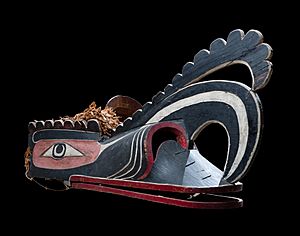

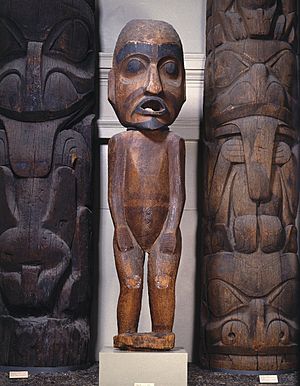

Kwakwakaʼwakw art includes many different crafts. These include totems, masks, textiles, jewelry, and carved objects. Their art ranges from transformation masks to 40 ft (12 m) tall totem poles. Cedar wood was the favorite material for sculpting and carving. This wood was easy to find in the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw lands.

Totems were carved with strong cuts, looking quite realistic, and used bold paints. Masks are a big part of Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw art. Masks are important for showing the characters in Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw dance ceremonies.

Woven textiles included the Chilkat blanket, dance aprons, and button cloaks. Each had Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw designs. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw used many materials for jewelry. These included ivory, bone, abalone shell, copper, and silver. Important people often wore these decorations on their clothes.

Music and Ceremonies

Kwakwakaʼwakw music is an ancient art form, thousands of years old. The music is mainly used for ceremonies and rituals. It uses percussion instruments like log, box, and hide drums, as well as rattles and whistles. The four-day Klasila festival is an important cultural event with songs, dances, and masks. It happens just before the tsetseka, or winter season.

The Potlatch Ceremony

The potlatch culture of the Northwest Coast is very famous and well-studied. It is still practiced among the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw today. The beautiful artwork they and their neighbors are known for is also still made. The book Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch explains the potlatch. It shows the amazing artwork and stories that go with it. It also gives a look into the high-level politics and great wealth of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw chiefs.

When the Canadian government wanted to make First Nations people more like Europeans, they tried to stop the potlatch. A missionary named William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was "the most difficult obstacle" to Indigenous people becoming Christians or "civilized."

In 1885, the Indian Act was changed to make the potlatch illegal. The law said:

Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the "Potlatch" or the Indian dance known as the "Tamanawas" is guilty of a misdemeanour, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in a jail or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.

Oʼwax̱a̱laga̱lis, Chief of the Kwaguʼł "Fort Rupert Tribes," spoke to expert Franz Boas on October 7, 1886. Boas had come to study their culture. The Chief said:

We want to know whether you have come to stop our dances and feasts, as the missionaries and agents who live among our neighbors try to do. We do not want to have anyone here who will interfere with our customs. We were told that a man-of-war would come if we should continue to do as our grandfathers and great-grandfathers have done. But we do not mind such words. Is this the white man's land? We are told it is the Queen's land, but no! It is mine.

Where was the Queen when our God gave this land to my grandfather and told him, "This will be thine"? My father owned the land and was a mighty Chief; now it is mine. And when your man-of-war comes, let him destroy our houses. Do you see yon trees? Do you see yon woods? We shall cut them down and build new houses and live as our fathers did.

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, "Do as the Indian does"? It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us.

Later, the law was changed again. It also stopped guests from taking part in the potlatch. But the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw were too many for the government to control. The government could not enforce the law. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to make the offense less serious. This meant that agents, acting as judges, could try a case and give a sentence.

Today, in the 21st century, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw openly hold potlatches. They are committed to bringing back their ancestors' ways. Potlatches happen more and more often as families reclaim their traditions.

Homes and Shelter

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw built their homes from cedar planks. Cedar wood is very good at resisting water. Their houses were very large, from 50 to 100 ft (15 to 30 m) long. A house could hold about 50 people, usually families from the same clan. At the entrance, there was often a totem pole. It was carved with different animals, mythical figures, and family symbols.

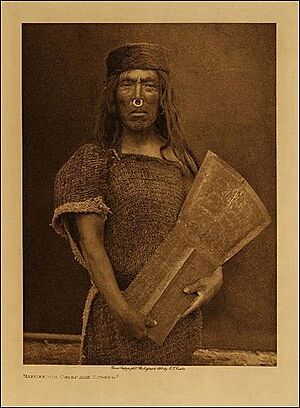

Clothing and Special Dress

In summer, men wore no clothing except jewelry. In winter, they often rubbed fat on themselves to stay warm. In battle, men wore armor and helmets made from red cedar. They also wore breech clouts made from cedar. During ceremonies, they wore cedar bark circles on their ankles and cedar breech clouts. Women wore skirts made of softened cedar. In winter, they added a cedar or wool blanket on top.

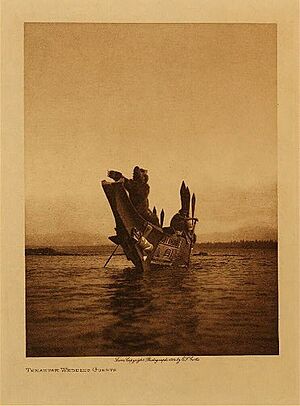

Travel and Transportation

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw travel was similar to other coastal people. Since they lived by the ocean, they mainly traveled by canoe. They carved dugout canoes from single cedar logs. These canoes were used by individuals, families, and communities. Sizes varied from large ocean-going canoes for long trade trips to smaller canoes for travel between villages. Some boats had buffalo fur inside to help keep people warm in the cold winters.

Notable Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw People

- Alfred Scow (1927-2013), first Aboriginal person to graduate from a BC law school, first Aboriginal lawyer in BC, and first Aboriginal judge in BC.

- Sonny Assu (b. 1975), an artist who works in many different art forms.

- Joe Peters Jr., artist and woodcarver.

- Beau Dick, artist and woodcarver.

- Gord Hill, artist, author, and Indigenous rights activist.

- Calvin Hunt (b. 1956), artist.

- Henry Hunt (1923-1985), artist.

- Richard Hunt (b. 1951), artist.

- Tony Hunt Sr. (1942-2017), artist.

- Charles Joseph, carver from the Maʼamtaglia-Tlowitsis tribe.

- Mungo Martin, woodcarver.

- David Neel, artist and writer.

- Ellen Neel, woodcarver.

- Marianne Nicolson (b. 1969), artist and academic.

- Spencer O'Brien (b. 1988), snowboarder.

- Joe Peters Jr. artist, woodcarver (b.1960-1994).

- Quesalid, medicine man and writer.

- Willie Seaweed, woodcarver.

- James Sewid, writer.

- Jody Wilson-Raybould, a politician.

See also

In Spanish: Kwakiutl para niños

In Spanish: Kwakiutl para niños

- Kwakiutl (statue)

- In the Land of the Head Hunters

- Sisiutl

- Dances of the Kwakiutl

- I Heard the Owl Call My Name

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |