Milutin Milanković facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Milutin Milanković

|

|

|---|---|

| Милутин Миланковић | |

Milutin Milanković, c. 1924

|

|

| Born | 28 May 1879 Dalj, Austria-Hungary (modern day Croatia)

|

| Died | 12 December 1958 (aged 79) Belgrade, PR Serbia, Yugoslavia

|

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Alma mater | TU Wien |

| Known for | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Thesis | Beitrag zur Theorie der Druck-kurven (1904) |

Milutin Milanković (born May 28, 1879 – died December 12, 1958) was a famous Serbian scientist. He was a mathematician, astronomer, and expert on climate. He also worked as a civil engineer. Milanković helped people understand science better.

He made two very important discoveries for global science. First, he created the "Canon of the Earth's Insolation". This describes the climates of all the planets in our Solar System. Second, he explained how Earth's long-term climate changes happen. These changes are caused by how the Earth moves around the Sun. We now call these changes Milankovitch cycles. His work helped explain the ice ages that happened long ago. It also helps us understand future climate changes.

Milanković started a new field called planetary climatology. He figured out the temperatures of the upper parts of Earth's atmosphere. He also calculated temperatures on planets like Mercury, Venus, Mars, and the Moon. He showed how the movement of planets (celestial mechanics) is linked to Earth sciences. This helped turn descriptive sciences into exact ones.

He was a respected professor at the University of Belgrade. He also directed the Belgrade Observatory. Milanković helped start a group for celestial mechanics in the International Astronomical Union. He was also a vice-president of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Before all this, he started his career as a construction engineer. He kept his interest in building throughout his life. He designed many reinforced concrete structures in Yugoslavia. He even had several patents for his inventions in this area.

Contents

Life of Milutin Milanković

Early Years and Education

Milutin Milanković was born in Dalj, a village by the Danube river. This was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. Milutin and his twin sister were the oldest of seven children. Their father was a merchant and died when Milutin was eight. His mother, grandmother, and an uncle raised him and his siblings. Sadly, three of his brothers died from tuberculosis when they were young.

Milutin was often sick as a child. He studied at home with his father, private teachers, and family friends. Some of these friends were famous thinkers and poets. He finished secondary school in Osijek in 1896.

In October 1896, at age seventeen, he moved to Vienna. He studied Civil Engineering at the TU Wien and graduated in 1902 with top grades. He later wrote about his math professor, Emanuel Czuber, saying his lectures were masterpieces of logic. After school and military service, Milanković got a loan to study more engineering. He researched concrete as a building material.

At age twenty-five, he earned his PhD. His thesis was about "Pressure Curves". This work helped in building bridges and other structures. He successfully defended his thesis on December 12, 1904. After this, he worked for an engineering company in Vienna. He used his knowledge to design buildings.

Building a Career in Engineering

In 1905, Milanković started working for a company in Vienna. He built dams, bridges, and other structures using reinforced concrete. One of his notable designs was an aqueduct for a power plant in Sebeș.

He invented a new type of reinforced concrete ceiling. He also published papers on how to build with reinforced concrete. In 1908, he showed that the best shape for a water tank with equally thick walls is like a water drop. He had six patents and was highly respected in his field. This work also brought him a lot of money.

Milanković worked as a civil engineer in Vienna until 1909. Then, he was offered a job as a professor at the University of Belgrade. He decided to focus on scientific research. Even after moving to Serbia, he continued some design work. In 1912, he designed reinforced bridges for a railway line.

Unlocking Earth's Climate Secrets

While studying climate, Milanković noticed a big puzzle: the ice ages. Scientists had wondered if changes in Earth's orbit caused climate shifts. Milanković decided to use math to figure this out. He studied spherical geometry, celestial mechanics, and theoretical physics.

He started this work in 1912. He felt that meteorology (the study of weather) needed more math. His first work described Earth's current climate. It showed how Sun's rays affect temperature after passing through the atmosphere. He published his first paper on this in 1912. His next paper, in 1913, correctly calculated the strength of insolation (sunlight reaching Earth). He created a math theory for Earth's climate zones.

His goal was a precise math theory. This theory would connect how planets heat up to how they move around the Sun. He wrote that such a theory would let them "go beyond direct observations." It would help rebuild Earth's past climate and predict its future. It would also give facts about climates on other planets. In 1914, he published a paper on the astronomical theory of ice ages. But this was a complex problem, and it took him thirty years to fully develop his theory.

World War I and Research in Captivity

In 1914, Milanković married Kristina Topuzović. They went on their honeymoon to his home village in Austro-Hungary. There, he heard that World War I had started. He was arrested because he was a citizen of Serbia.

His wife went to Vienna and spoke to Emanuel Czuber, Milanković's mentor. Professor Czuber used his connections to get Milanković released from prison. He was allowed to live in Budapest and continue his work.

In Budapest, Milanković met the director of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences library. He was allowed to work there and at the Central Meteorological Institute. Milanković spent four years in Budapest during the war. He used math to study the climates of the inner planets. In 1916, he published a paper on the climate of Mars. He calculated Mars' average temperature and found it was very cold. He also studied Venus and Mercury.

His calculations for the Moon were also important. He knew that one day on the Moon lasts 15 Earth days. He calculated that the Moon's surface temperature reaches +100.5 °C during the day. At night, it drops to −58 °C. Today, we know the actual temperatures are similar.

After the war, Milanković returned to Belgrade in 1919. He became a full professor at the University of Belgrade. From 1912 to 1917, he published seven papers on climate theories for Earth and other planets. He created a precise math model for climate. This model could reconstruct past climates and predict future ones. He established the astronomical theory of climate.

In 1920, he published a book in Paris called "Mathematical Theory of Heat Phenomena Produced by Solar Radiation." This book was quickly recognized by meteorologists.

Orbital Cycles and Ice Ages

Milanković's ideas about how Earth's orbit causes ice ages gained support. Climate expert Wladimir Köppen and geophysicist Alfred Wegener found his work useful. In 1922, Köppen asked Milanković to extend his calculations from 130,000 years to 600,000 years. They agreed that summer sunlight was key to climate.

Milanković spent 100 days calculating changes in solar radiation. He focused on latitudes in the northern hemisphere that he believed were most sensitive to climate changes. These calculations showed how sunlight variations matched the timing of ice ages. Köppen and Wegener included Milanković's solar curve in their 1924 book, "Climates of the geological past."

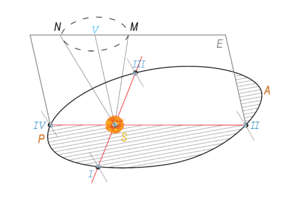

Milanković believed the Sun was the main source of heat and light. He looked at three main cycles of Earth's movement:

- Eccentricity: How elliptical Earth's orbit is (about a 100,000-year cycle).

- Axial tilt: The tilt of Earth's axis (about a 41,000-year cycle, from 22.1° to 24.5°).

- Precession: The wobble of Earth's axis (about a 23,000-year cycle).

Each cycle happens over a different time. Each affects how much solar energy Earth receives. These changes in Earth's orbit lead to changes in insolation. This is the amount of heat a place on Earth gets. These orbital variations are influenced by the gravity of the Moon, Sun, Jupiter, and Saturn. They form the basis of the Milankovitch cycles.

Milanković simplified how to calculate planetary movements. He used a new way to describe orbits with just two vectors. This made calculations much easier. He also used more accurate values for the masses of the planets.

The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts made Milanković a member in 1920. He became a full member in 1924. He also represented Yugoslavia at the International Meteorological Organization for many years.

In 1926, Köppen asked Milanković to extend his calculations to a million years. This was to help a geologist named Barthel Eberl who was studying older ice ages. Eberl published Milanković's curves in 1930.

Between 1925 and 1928, Milanković wrote a popular science book called Through Distant Worlds and Times. It was written as letters to an unknown woman. The book explored the history of astronomy and climate science. It imagined visits to different times and places. Milanković explained complex ideas in a simple way.

In 1930, Milanković wrote part of a book called Mathematical science of climate and astronomical theory of the variations of the climate. In 1934, he published Celestial Mechanics, a textbook that used vector math to solve problems.

From 1935 to 1938, Milanković calculated how ice cover depends on changes in sunlight. He found a mathematical link between summer sunlight and the height of the snow line. This helped geologists understand how ice covers changed over the last 600,000 years.

Exploring Polar Wandering

Conversations with Alfred Wegener, who developed the continental drift theory, made Milanković interested in Earth's interior and how the poles move. Wegener had found large coal reserves on the Svalbard Islands in the Arctic Ocean. These could not have formed at the islands' current location. This suggested the continents had moved.

Milanković believed that continents "float" on a somewhat fluid layer beneath them. He thought that the positions of continents affect Earth's centrifugal force. This could make the Earth's axis of rotation move.

From 1930 to 1933, Milanković worked on how the Earth's poles move over long periods. He treated Earth as a fluid body that acts like a solid for short forces, but like an elastic body for longer ones. He created a math model to explain how the poles move. He mapped the path of the poles over the past 300 million years. He found that changes happen every 5 to 30 million years. He concluded that the Earth's outer shell moves over its base.

Milanković published his paper on pole movements in 1932. He also wrote sections for a geophysics handbook by Beno Gutenberg in 1933. His ideas on pole shifts were presented at a conference in Athens in 1934.

Most scientists were unsure about Wegener's and Milanković's theories at first. However, in the 1950s and 1960s, a new field called palaeomagnetism emerged. This field studied Earth's magnetic field in rocks over time. Evidence from palaeomagnetism supported the idea of continental drift. This led to the modern theory of plate tectonics.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1939, Milanković started to gather all his scientific work on solar radiation. This big book was called "Canon of Insolation of the Earth and Its Application to the Problem of the Ice Ages." It covered almost three decades of his research. It explained universal laws that could explain cyclical climate change and the 11 ice ages. These are now known as his Milankovitch cycles.

He finished the "Canon" manuscript on April 2, 1941. This was just four days before Nazi Germany attacked Yugoslavia. During the bombing of Belgrade on April 6, 1941, the printing house was destroyed. But most of his printed pages were safe in the warehouse. After the occupation, two German officers who were geology students visited Milanković. He gave them the only complete copy of his "Canon" to send to a professor in Germany. This ensured his work would be saved.

The "Canon" was published in German in 1941 by the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. It was a large book with 626 pages. During the German occupation, Milanković stayed out of public life. He wrote his autobiography, "Recollection, Experiences and Vision," which was published in 1952.

Contributions to History of Science

After the war, Milanković became vice president of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (1948–1958). He also joined a celestial mechanics group in the International Astronomical Union in 1948. In 1954, he received a special diploma from the Technical University of Vienna. In 1955, he joined the German Academy of Naturalists "Leopoldina".

Milanković also wrote many books on the history of science. These included books on Isaac Newton, Pythagoras, Democritus, Aristotle, and Archimedes. He also wrote about the history of astronomy and chemistry.

Milutin Milanković died in Belgrade in 1958 after a stroke. He is buried in his family cemetery in Dalj.

Lasting Impact and Recognition

After Milanković's death, many scientists doubted his "astronomical theory." But ten years later, his theory was reconsidered. His book was translated into English in 1969.

Slowly, his theory was proven to be correct. A project called CLIMAP (Climate: Long Range Investigation, Mapping and Production) finally confirmed the Milankovitch cycles in 1972. Scientists studied deep-sea cores and found that climate changes over the past 500,000 years matched changes in Earth's axis tilt and precession.

Later projects like COHMAP (Cooperative Holocene Mapping Project) and SPECMAP (Spectral Mapping Project) also showed the key role of astronomical factors in climate change. In 1999, studies of oxygen isotopes in ocean sediments further supported his theory. While the general idea of orbital forcing is accepted, scientists still discuss the details of how these changes affect climate.

Other Scientific Work

On Light and Relativity

Milanković wrote two papers on relativity. In 1912, he wrote about the Michelson–Morley experiment. This experiment showed strong evidence against the idea of a "luminiferous aether." He discussed how this experiment supported the idea that the speed of light is the same for everyone, no matter how they are moving.

Revised Julian Calendar

In 1923, Milanković suggested changes to the Julian calendar. He proposed a new rule for leap years. Some Eastern Orthodox churches adopted parts of his calendar in May 1923. However, the dates for Easter are still calculated using the old Julian calendar.

Awards and Honors

To honor his work in astronomy, a crater on the far side of the Moon was named Milankovic in 1970. A crater on Mars was also named after him in 1973. Since 1993, the European Geosciences Union has given out the Milutin Milankovic Medal. This award is for important work in long-term climate studies. An asteroid discovered in 1936 is also named 1605 Milankovitch.

NASA recognized Milanković as one of the top fifteen minds in Earth sciences. He also received important awards like the Order of Saint Sava and the Order of the Yugoslav Crown.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Milutin Milanković para niños

In Spanish: Milutin Milanković para niños

- History of climate change science

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |