Munir Ahmad Khan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Munir Ahmad Khan

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 20 May 1926 |

| Died | 22 April 1999 (aged 72) |

| Citizenship | Pakistan |

| Alma mater | Government College University University of Punjab North Carolina State University |

| Known for | Pakistan's nuclear deterrent program and nuclear fuel cycle |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Nuclear reactor physics |

| Institutions | Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission International Atomic Energy Agency Institute of Applied Sciences University of Engineering and Technology International Center for Theoretical Physics |

| Thesis | Investigations on Model Surge Generator (1953) |

| Academic advisors | Walter Zinn |

Munir Ahmad Khan (Urdu: منير احمد خان; 20 May 1926 – 22 April 1999) was a Pakistani nuclear reactor physicist. He is often called the "father of the atomic bomb program" in Pakistan. He played a very important role in developing Pakistan's nuclear weapons after the war with India in 1971.

From 1972 to 1991, Khan was the chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). He led the secret program to develop atomic weapons. This included everything from early efforts to the final nuclear tests in May 1998. Early in his career, he worked at the International Atomic Energy Agency. He used his position there to help create the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Italy. He also helped start an annual science conference in Pakistan. As the head of PAEC, Khan believed in having nuclear weapons to balance power with India. He focused on making plutonium for weapons and was involved in Pakistan's important national security projects.

After leaving the Atomic Energy Commission in 1991, Khan spoke publicly about using nuclear power generation for electricity in Pakistan. He also taught physics for a short time at the Institute of Applied Sciences in Islamabad. Even though he faced some challenges for supporting peaceful nuclear use, he was later honored with the Nishan-i-Imtiaz (Order of Excellence) in 2012. This award was given by the President of Pakistan, thirteen years after Khan's death.

Contents

Munir Ahmad Khan's Early Life and Education

Munir Ahmad Khan was born in Kasur, Punjab, in British India on May 20, 1926. His family was Pashtun and had lived in Punjab for a long time. He finished high school in 1942 in Kasur. Then, he went to Government College University in Lahore. There, he was a classmate of Abdus Salam, who later won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978.

In 1946, Khan earned a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree in mathematics. In 1949, he enrolled at the Punjab University to study engineering. He graduated in 1951 with a Bachelor of Science in Engineering (BSE) in electrical engineering. He was recognized for his excellent grades. After graduating, Khan taught engineering at the University of Engineering and Technology (UET) in Lahore. He then received a Fulbright Scholarship to study in the United States.

In the U.S., Khan attended North Carolina State University. He continued his studies in electrical engineering and earned a Master of Science (MS) degree in 1953. His master's thesis was about "Investigation on Model Surge Generator." This work focused on how impulse generators could be used.

Khan's interests shifted from electrical engineering to physics while in the United States. He began taking advanced courses in thermodynamics and the kinetic theory of gases. In 1953, he joined the Atoms for Peace program. This program offered training in nuclear engineering at North Carolina State University and Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois. In 1957, Khan completed his training and earned an MS degree in nuclear engineering. He focused heavily on nuclear reactor physics.

Starting His Career in Nuclear Science

After graduating from North Carolina State University, Khan worked for engineering companies like Allis-Chalmers and Commonwealth Edison. He helped design power generation equipment. He also worked on the Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I). This experience sparked his interest in the practical uses of physics.

In 1957, Khan became a research associate at the Argonne National Laboratory. He trained as a nuclear reactor physicist. He worked on improving the Chicago Pile-5 (CP-5) reactor. He also briefly worked as a consultant for American Machine and Foundry.

Working at the International Atomic Energy Agency

In 1958, Khan moved to Austria to work for the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). He joined the nuclear power division in a senior role. He was the first Asian from a developing country to hold such a high position there. He also advised the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) on energy matters. He represented Pakistan at many conferences about nuclear power.

At the IAEA, Khan focused on reactor technology. He studied how nuclear reactors could be used efficiently. He also oversaw technical aspects of reactors and surveyed sites for nuclear power plants. His work on neutron transport in reactors earned him the nickname "Reactor Khan" among his colleagues. He also became skilled in producing reactor-grade plutonium from nuclear reactors.

Khan organized over 20 international conferences on topics like heavy water reactors, gas-cooled reactors, and nuclear power plant efficiency. He also worked on extracting fuel from uranium and producing plutonium. In 1961, he wrote a report for the IAEA on small nuclear power reactors. He served as a scientific secretary for United Nations conferences on peaceful uses of atomic energy in 1964 and 1971. From 1986 to 1987, Khan was the Chairman of the IAEA Board of Governors. He also led Pakistan's delegations to IAEA conferences for many years.

Helping Create a Global Science Center

While studying in Lahore in the 1940s, Khan became friends with Abdus Salam. Khan supported Salam's idea to improve science education in Pakistan. While at the IAEA, Khan saw the importance of Theoretical physics. He was especially interested in how it could be used in nuclear reactors.

In 1960, Salam discussed with Khan the idea of creating a research institute for mathematical sciences under the IAEA. Khan immediately supported this idea. He worked hard to get financial support and sponsorship from the IAEA. This led to the creation of the International Center for Theoretical Physics (ICTP). Many countries supported the idea, but one influential member, Isidor Isaac Rabi from the United States, was against it. Khan convinced Sigvard Eklund, the Director of the IAEA, to help. This led to the ICTP being built in Trieste, Italy.

Khan oversaw the construction of the ICTP in 1967. He also played a key role in starting the annual summer science conference in 1976, following Salam's advice. Even after retiring from PAEC, Khan cared about physics education in Pakistan. In 1997, he joined the Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences to teach physics. He had helped set up its academic programs in 1976. In 1999, Khan was a guest speaker at the opening of the National Center for Physics. This lab works closely with the ICTP in Italy.

A Key Advisor for Pakistan's Future

After visiting India's Bhabha Atomic Research Centre in 1964 and the second war with India in 1965, Khan became very concerned about international politics. He shared his worries with the Government of Pakistan. He met with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was the Foreign Minister at the time, in Vienna. Khan discussed the need for Pakistan to have a nuclear deterrent to protect itself from nuclear threats.

On December 11, 1965, Bhutto arranged a meeting between Khan and President Ayub Khan in London. Khan tried to convince the President to develop nuclear weapons, explaining that it would not be too expensive. However, President Ayub Khan did not agree. He felt Pakistan was too poor and believed they could "buy it off the shelf" if needed. After the meeting, Khan met with Bhutto, who told him, "Don't worry. Our turn will come."

Throughout the 1970s, Khan supported Bhutto's political party. President Bhutto praised Khan's work and promised to fund nuclear programs. This happened at the opening of the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant in 1972. Khan continued to visit Bhutto in prison after the military took over the government in 1977. He kept Bhutto updated on the nuclear program's progress.

Leading Pakistan's Atomic Energy Program

In 1972, Khan resigned from the IAEA and became chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). He replaced I. H. Usmani. By March 1972, Khan presented a detailed plan to the Ministry of Energy. His plan was to connect all of Pakistan's energy systems to nuclear power. This would reduce the country's reliance on hydroelectricity.

On November 28, 1972, Khan, along with Abdus Salam, joined President Bhutto at the opening of the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (KANUPP). This was a major step towards Pakistan becoming a nuclear power. Khan was vital in keeping KANUPP running. When its chief scientist, Wazed Miah, left, Khan set up a training facility with Karachi University. This helped train new engineers. In 1976, when Canada stopped supplying uranium and parts for KANUPP, Khan worked to develop the nuclear fuel cycle without foreign help. This ensured the plant continued to produce electricity. He established a fuel cycle facility near the power plant.

From 1975 to 1976, Khan worked with France's Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA). He aimed to get a reprocessing plant to produce plutonium and a nuclear power plant in Chashma. Negotiations with France were difficult, especially when the United States worried about nuclear proliferation. Khan wanted to learn from France so PAEC could build the plants themselves. However, Bhutto's government wanted to import them directly. In 1973–77, Khan negotiated for the Chashma Nuclear Power Plant. He advised signing an IAEA safeguard agreement with France for funding. When France left the project, PAEC took over. Khan later negotiated with China for funding in 1985–86.

In 1977, Khan strongly opposed France's idea to change the reprocessing plant's design. This change would have stopped the production of military-grade plutonium. Khan advised the government to refuse the change. PAEC had already built the plant and made parts locally. This plant is now known as the Khushab Nuclear Complex.

In 1982, Khan expanded nuclear technology to help agriculture. He established the Nuclear Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIAB) in Peshawar. He also moved PAEC into medical physics research. From 1983 to 1991, he secured government funding for several cancer research hospitals in Pakistan.

Building Pakistan's Nuclear Program

On December 16, 1971, Pakistan agreed to a ceasefire, ending its third war with India. This led to East Pakistan becoming the independent country of Bangladesh. When Khan heard this news, he returned to Pakistan from Austria.

On January 20, 1972, President Bhutto held a meeting with scientists in Multan. He approved a fast-paced program to develop an atomic bomb for "national survival." President Bhutto asked Khan to lead this program. Khan dedicated himself fully to the task. He helped with complex calculations for fast neutrons. Even without a doctorate, his experience as a nuclear engineer at the IAEA allowed him to guide senior scientists on secret projects. Khan quickly impressed the military with his wide knowledge of engineering, metallurgy, and chemistry.

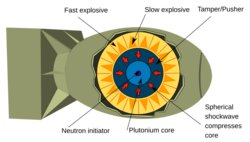

In December 1972, Abdus Salam asked two theoretical physicists, Riazuddin and Masud Ahmad, to work with Khan. They formed the "Theoretical Physics Group" (TPG) within PAEC. This group performed detailed mathematical calculations on fast neutron temperatures. Salam oversaw the TPG, with Khan assisting in calculations for the atomic bomb's binding energy. The Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, a national lab, quickly expanded. Khan brought top physicists from Quaid-e-Azam University to conduct secret research there.

In 1972, early efforts focused on a plutonium-boosted fission implosion-type device, code-named Kirana-I. In March 1974, Khan and Salam met with Muhammad Hafeez Qureshi, a mechanical engineer, and Dr. Zaman Shaikh, a chemical engineer. They discussed the need for explosive lenses and a reflective tamper. These parts were needed to make the fissile material dense enough for a nuclear reaction. This project required manufacturing special parts. Khan asked the Corps of Engineers to build the Metallurgical Laboratory (ML) near the Pakistan Ordnance Factories in Wah. The project then moved to the ML.

In March 1974, Khan took over the TPG from Salam, who left Pakistan. Khan also started a uranium enrichment program as a backup for producing fissile material. He assigned Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmood to work on gaseous diffusion and Shaukat Hameed Khan on laser isotope separation. The uranium enrichment project sped up after India's "Smiling Buddha" nuclear test in May 1974. Khan confirmed the test's radiation using data from I. H. Qureshi. Khan then called a meeting where gaseous diffusion was chosen over laser isotope separation. In 1975, Khalil Qureshi, a physical chemist, joined the uranium project. In 1976, Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, a metallurgist, joined. Due to technical issues, the program later moved to the Khan Research Laboratories in Kahuta, with A. Q. Khan as its chief scientist.

By 1976–77, the atomic bomb program shifted from civilian to military control. Khan remained the technical director of the overall bomb program.

The Nuclear Tests: Chagai-II

In 1975, Khan worked with the Corps of Engineers to choose mountain ranges in Balochistan for their isolation and security. He asked Ishfaq Ahmad and Ahsan Mubarak, a seismologist, to survey the mountains with help from the Corps of Engineers. They looked for high, rocky granite mountains that could withstand a nuclear blast of over 40 kilotons. They chose sites in Chagai, Kala-Chitta, Kharan, and Kirana in 1977–78.

On March 11, 1983, the various groups at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology successfully conducted the first "cold-test" of their atomic bomb design. This test was code-named Kirana-I. A "cold test" is a test of a nuclear weapon design without the fissile material. This prevents any nuclear reaction. Khan validated the preparations and calculations. Ishfaq Ahmad led the team of scientists. Other important people who witnessed the test included Ghulam Ishaq Khan and senior military officers.

Khan later recalled about witnessing the test:

In 1977–80, the PAEC completed the designs of the iron-steel tunnels in Chagai region. On 11 March 1983, we successfully conducted [our] (cold) test of a working design of atomic bomb. That evening, I went to President Zia with the news that Pakistan was now ready to make an atomic bomb. We conducted this cold test long before the fissile material was available for actual test. We were ahead of others.....

—Munir Ahmad Khan,Statement given to news media in 1999.

Despite challenges, Khan emphasized the importance of plutonium. He disagreed with Abdul Qadeer Khan, who preferred a uranium atomic bomb. From the start, studies focused on the "implosion-type" design, which became known as the Chagai-II in 1998. Khan and Abdul Qadeer also considered "gun-type" designs, which are simpler and use U235. However, they abandoned gun-type studies because of the risk of a "nuclear fizzle" (a failed chain reaction). Khan's support for the plutonium implosion-type design was proven correct with the test of a plutonium device, Chagai-II. This device had the largest yield of all the tested weapons.

President Zia, despite Khan's political views, respected his knowledge of national security. During a visit to the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology in November 1986, he praised Khan:

It has been a matter of great pride and satisfaction to see what all is going on in (Pakistan) Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). It was heartening to see the progress that has taken place..... I congratulate Munir and his associates for all that they have done.... The People of Pakistan are proud of their achievements and pray for their success in the future.

Promoting Peace Through Nuclear Diplomacy

Even though Pakistani politicians made public statements, the atomic bomb program was kept top secret. Khan became a national spokesperson for science in the government. He pushed for the Space Research Commission to be separate from PAEC. He also supported launching Pakistan's first satellite to compete with India in the space race. Unlike his predecessor, Khan believed in an arms race with India to maintain a balance of power. He secured funding for military "black" projects and national security programs. By 1979, Khan moved PAEC's defense production role to the KRL. He also founded the National Defence Complex (NDC) in 1991.

At international conferences, Khan criticized India's nuclear program. He believed it had military goals and threatened regional stability. He defended Pakistan's non-nuclear weapon policy and its nuclear tests. He once said:

In 1972, we (Pakistan) made a [nuclear policy] statement... that [Pakistan] wanted a nuclear-free zone in South Asia (so) that the resources in the sub-continent could be focused on solving problems of poverty and deprivation of [one] billion people in this region of the world. But India did not listen to us (Pakistan).... Now that we have responded to India's nuclear aggression, Pakistan hope that they will listen to us ...

—Munir Ahmad Khan,stating his views on Operation Shakti in 1999

In 1981, Israel's Operation Opera destroyed Iraq's Osirak Nuclear Plant. Pakistani intelligence learned of Indian plans to attack Pakistan's nuclear sites. In 1983, diplomat Abdul Sattar shared this report with Khan. While at a nuclear safety conference in Austria, Khan met Indian physicist Raja Ramanna. They discussed nuclear physics, and Khan invited Ramanna to dinner. Ramanna confirmed the intelligence report.

At this dinner, Khan reportedly warned Ramanna about a possible retaliatory nuclear strike at Trombay if India attacked. He urged Ramanna to tell this to Indira Gandhi, the Indian Prime Minister. The message reached the Indian Prime Minister's Office. In 1987, the Non-Nuclear Aggression Agreement treaty was signed. This agreement aimed to prevent nuclear accidents and accidental detonations between India and Pakistan.

Later Years: Teaching and Advocating for Science

In the 1980s, Khan became a science advisor in the government. He advised the government to sign an agreement with China to fund the Chashma Nuclear Power Plant in 1987. In 1990, Khan advised the government to negotiate with France for building another nuclear power plant in Chashma.

As chairman of PAEC in 1972, Khan helped expand the "Reactor School." This school was in a lecture room at the Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology. In 1976, Khan moved the school to Islamabad and renamed it the "Centre for Nuclear Studies (CNS)." He became an unpaid part-time professor of physics there.

After retiring from PAEC in 1991, Khan became a full-time professor at the CNS. He continued to push for the CNS to become a university. In 1997, his goal was achieved. The government granted the CNS university status and renamed it the Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (PIEAS).

Munir Ahmad Khan's Last Years and Legacy

Khan bought a home in Islamabad in 1972. He passed away on April 22, 1999, at age 72, due to complications from heart surgery. He was survived by his wife, Thera, three children, and four grandchildren.

After Abdus Salam left his position in 1974, Khan became a symbol for scientists who believed they could control how their research was used. During the atomic bomb program, Khan represented the moral responsibility of scientists. He also contributed to the rise of science in Pakistan while preventing the project from becoming too political.

In the 1990s, Khan became increasingly worried about the dangers of nuclear technology. He emphasized how difficult it was to manage scientific knowledge between scientists and lawmakers. This was especially true when political concerns limited the sharing of scientific ideas. While working on the atomic bomb program, Khan was very secretive. He avoided meeting journalists and encouraged scientists to stay away from the public due to the sensitive nature of their work.

His colleagues remember Khan as a brilliant researcher and an inspiring teacher. He is considered the founder of applied physics in Pakistan. In 2007, Farhatullah Babar described Khan as having a "tragic fate but consciously genius." Years later, many of Khan's colleagues and political friends urged the government to honor him. In 2012, President Asif Ali Zardari awarded Khan the prestigious Nishan-e-Imtiaz. This was a gesture of political recognition after his death.

One of Khan's greatest achievements was leading the atomic bomb program. It was similar to the Manhattan Project. He prevented politicians and military officials from misusing or politicizing the program. Under Khan's leadership, the project focused on developing atomic weapons for national defense. It also diversified nuclear technology for medical uses. He saw this secret atomic bomb project as "building science and technology for Pakistan."

As a military and public policy maker, Khan was a technocrat leader. He helped shift the relationship between science and the military. He also contributed to the idea of "big science" in Pakistan. During the Cold War, scientists became deeply involved in military research. This was due to threats from Afghanistan and India. Scientists volunteered their help, leading to powerful tools like laser science and operations research. Khan was an intellectual physicist who became a disciplined military organizer. He showed that scientists were not just "in the clouds." He proved that knowledge of complex subjects like the atomic nucleus had important "real-world" uses.

Throughout his life, Khan received many national awards and honors:

|

|

Quotes by Khan

- "We have to understand that nuclear weapons are not a play thing to be bandied publicly. They have to be treated with respect and responsibility. While they can destroy the enemy, they can also invite self destruction."

- "While we were building capabilities in the nuclear fuel cycle, we started in parallel the design of a nuclear device, with its trigger mechanism, physics calculations, production of metal, making precision mechanical components, high-speed electronics, diagnostics, and testing facilities. For each one of them, we established different laboratories."

- "Many sources were tapped after the decision to go nuclear. We were simultaneously working on 20 labs and projects under the administrative control of PAEC, every one the size of Khan Research Laboratories."

- "On 11 March 1983, we successfully conducted the first cold test of a working nuclear device. That evening, I went to General Zia with the news that Pakistan was now ready to make a nuclear device."

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |