Native American identity in the United States facts for kids

Native American identity in the United States is about how people define what it means to be a "Native American" or "American Indian." This is a big question for people who see themselves as Native American and for those who don't. Everyone wants a clear definition for legal, social, and personal reasons. Many things help define "Indianness," like culture, society, family history (genes/biology), law, and how someone feels about themselves (self-identity).

One important question is whether this definition should change over time or stay the same. Some believe it should change as Native Americans adapt to modern society. Others think it should evolve as groups develop and renew their ethnic identity. This question of identity is common for many native groups around the world.

The future of their identity is very important to Native Americans. Activist Russell Means often talked about how the Native American way of life was changing. He worried about losing traditions, languages, and sacred places. He feared there might soon be no more true Native Americans, only "Native American Americans," like Polish Americans. Even though the number of Native Americans has grown a lot since 1890, fewer people are carrying on tribal traditions. Means said, "We might speak our language, we might look like Indians and sound like Indians, but we won’t be Indians."

Contents

What Does "Native American" Mean?

There are many ways to define what it means to be Native American. Some definitions try to apply to everyone, while others are for specific reasons, like who can join a tribe or for legal matters. People often want their personal identity to match how society and laws define them.

It used to be easier to tell who was American Indian in the early 1900s, but today it's more complex. Malcolm Margolin, who helps edit News From Native California, said, "I don’t know what an Indian is... [but] Some people are clearly Indian, and some are clearly not." Cherokee Chief Wilma Mankiller (who led from 1985–1995) agreed, saying: "An Indian is an Indian regardless of the degree of Indian blood or which little government card they do or do not possess."

It's also tricky to define Native American identity based on "race." Many people say that race is a social idea (or political) rather than a biological fact. Writer Steve Russell (2002) pointed out that American law sometimes made it easy for Native Americans to "disappear" into the white population. This was often linked to the idea of "Manifest Destiny," which was the belief that the United States was meant to expand across the continent. Russell reminds us that Native Americans are "members of communities before members of a race."

Traditional Ways of Defining Identity

Traditional ideas of "Indianness" are very important. There's a feeling of "peoplehood" that connects Native American identity to sacred traditions, special places, and a shared history as native people. This idea goes beyond legal or academic definitions. Language is also a key part of identity. Learning Native languages, especially for young people, helps tribes survive.

Some Native American artists find traditional definitions especially meaningful. Crow poet Henry Real Bird says, "An Indian is one who offers tobacco to the ground, feeds the water, and prays to the four winds in his own language." Pulitzer Prize-winning Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday has a definition that focuses on personal experience: "An Indian is someone who thinks of themselves as an Indian. But that's not so easy to do and one has to earn the entitlement somehow. You have to have a certain experience of the world in order to formulate this idea. I consider myself an Indian; I've had the experience of an Indian. I know how my father saw the world, and his father before him."

Some experts say that Native American identity is like a story that a group creates together. This means identity is shaped by how a group remembers its past, tells its stories, and understands its myths. So, cultural identity is built through shared history and culture. Identity might not be just about a person's core being, but also about their place in political and social situations.

Blood Quantum and Ancestry

One way to define if someone is Native American is by their "blood quantum" (how much Native American ancestry they have) or by documented Native American family history. About two-thirds of all federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States require a certain blood quantum to be a member. Having Native American heritage is a must for joining most American Indian Tribes.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 used three main rules: being a tribal member, having ancestors from the tribe, and having a certain blood quantum (one half). This law greatly influenced how "Indian" was defined. Some people worry that using blood quantum is a problem because Native Americans marry people from other groups more often than any other group in the United States. This could eventually lead to them blending into the larger multiracial American society.

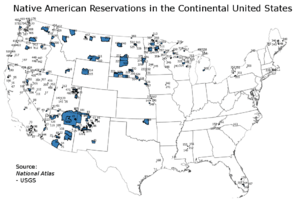

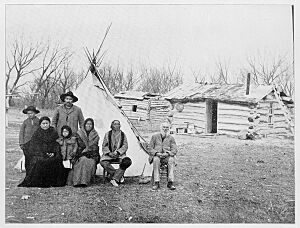

Living on Tribal Lands

Living on tribal lands and Indian reservations is also connected to keeping traditions alive. Being close to other Native Americans and tribal lands can play a role in how someone sees themselves as Native American.

How Others Define Native Americans

How Europeans saw "Indianness" has shaped how Native Americans see themselves. It also created stereotypes that can negatively affect how Native Americans are treated. The "noble savage" is a famous stereotype. Early American colonists had other ideas too. For example, some thought Native Americans lived like their own ancestors, such as the Picts or Britons, before they became "tame and civil."

In the 1800s and early 1900s, the United States government had policies that attacked Native American culture. They tried to force Native Americans to become like European Americans. These policies included banning traditional religious ceremonies, forcing hunter-gatherer people to farm unsuitable land, cutting hair, and making people convert to Christianity by holding back food. Children were forced to go to boarding schools where they couldn't speak Native American languages. Travel between reservations was restricted. In areas of the U.S. that were under Spanish control until 1810, where most people were Indigenous, Spanish officials had similar policies.

United States Government Definitions

Some experts say there's a link between how Native Americans see themselves and their legal status as tribal members. There are 561 federally recognized tribal governments in the United States. These tribes have the right to set their own rules for who can be a member. Today, laws about Native Americans often define an "Indian" as someone who is a member of a federally recognized tribe. An "Indian tribe" is any tribe, band, or community recognized by the United States.

The government and many tribes prefer this definition because it lets tribes decide who their members are. However, some people criticize this. They say the federal government has historically set conditions on membership, so its influence is still there. This means that if you belong to a federally recognized tribe, you have a stronger claim to a Native American identity. Many people who feel they are Native American don't have this recognition. Holly Reckord, an anthropologist who works for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), says that many people who seek membership have no Native American ancestry. She wonders why someone would choose that identity if they have no trace of it, rather than their Irish or Italian heritage.

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 tries to deal with the limits of definitions based on federally recognized tribal membership. This law also considers state-recognized tribes and allows someone to be recognized as an "Indian artisan" even without tribal membership. This means people who identify as Native American can legally label their products as "Indian made," even if they aren't members of a federally recognized tribe. During hearings for the law, one artist, whose father was Seneca and who grew up on a Seneca reservation, said that tribes have the right to set rules for who can enroll. But she felt they shouldn't tell people without enrollment numbers that they aren't of Native American heritage. She argued that denying her heritage and prosecuting her for it would deny her civil liberties and be racial discrimination.

Some critics believe that using federal laws to define "Indian" lets the government keep control over Native Americans. They say "Indianness" becomes a strict legal term defined by the BIA, instead of being about tradition, history, and culture. For example, some groups who say they are descendants of tribes from before European contact haven't been able to get federal recognition. On the other hand, Native American tribes have helped set policies with the BIA on how tribes should be recognized. Rennard Strickland, an expert in Indian Law, says the federal government uses the recognition process to "divide and conquer Indians." He believes that arguing over who is "more" Indian can distract people from shared goals.

Self-Identification

Sometimes, people can simply say they are Native American without outside proof. For example, you can often choose to identify as Indian on a census form or a college application. A "self-identified Indian" is someone who might not meet the legal rules of the U.S. government or a specific tribe, but who feels and expresses their own identity as Native American. Many people who don't meet tribal rules still identify as Native American because of family history, culture, or other reasons.

The U.S. Census lets people check any ethnicity without needing proof. So, the census allows individuals to self-identify as Native American just by checking the box for "Native American/Alaska Native." In 1990, about 60% of the 1.8 million people who identified as American Indian on the census were actually enrolled in a federally recognized tribe. Self-identification allows for a wider range of ideas about "Indianness." This includes nearly half a million Americans who don't receive benefits because:

- they are not enrolled members of a federally recognized tribe, or

- they are full members of tribes that have never been recognized, or

- they are members of tribes whose recognition was ended by the government in the 1950s and 1960s.

Identity is often a personal matter, based on how someone feels about themselves and their experiences. Horse (2001) describes five things that influence how someone sees themselves as Indian:

- How connected they are to their Native American language and culture.

- How true their American Indian family history is.

- How much they follow a traditional American Indian way of thinking (focusing on balance, harmony, and Indian spirituality).

- Their self-concept as an American Indian.

- Whether they are enrolled in a tribe (or not).

Sociologist Joane Nagel from the University of Kansas noted that the number of Americans reporting American Indian as their race on the U.S. Census tripled from 1960 to 1990. She links this to federal Indian policy, American ethnic politics, and Native American activism. Much of this "growth" was due to "ethnic switching," where people who identified with one group later identified with another. This is possible because we increasingly see ethnicity as a social idea. Also, since 2000, the U.S. census has allowed people to check multiple ethnic categories, which has also increased the American Indian population. However, self-identification can have problems. Sometimes, people jokingly say that the largest tribe in the United States might be the "Wantabes" (people who want to be Indian but aren't).

Garroutte points out practical problems with self-identification. She mentions struggles faced by Native American service providers who deal with many people claiming distant Native American ancestors. She quotes a social worker saying, "Hell, if all that was real, there are more Cherokees in the world than there are Chinese." She writes that if an individual's claim is valued more than a tribe's right to define its own citizens, it can threaten tribal sovereignty (a tribe's right to govern itself).

Personal Reasons for Self-Identification

Many people want broader definitions of "Indian" for personal reasons. Some people whose careers involve their Native American heritage face challenges if their appearance, behavior, or tribal membership doesn't fit legal or social definitions. Some simply long for recognition. Cynthia Hunt, who identifies as a member of the state-recognized Lumbee tribe, says: "I feel as if I'm not a real Indian until I've got that BIA stamp of approval... You're told all your life that you're Indian, but sometimes you want to be that kind of Indian that everybody else accepts as Indian."

Sometimes, looking "Indian" can seem more important than one's family history or legal status. Native American Literature professor Becca Gercken-Hawkins writes about the difficulty of being recognized if you don't look Indian. She identifies as Cherokee and Irish American. Even though she doesn't look especially Indian with her dark curly hair and light skin, she meets her tribe's blood quantum standards. Her family has worked for years to get the documents needed to enroll in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Because of her appearance and lack of enrollment, she expects questions about her identity. She was surprised when a fellow student seriously advised her to straighten her hair and get a tan before interviews. When she joked about putting a feather in her hair, the student said a feather might be too much, but she should at least wear traditional Native jewelry.

Louis Owens, an author of Choctaw and Cherokee descent who is not enrolled in a tribe, talks about his feelings of not being a "real Indian" because he's not enrolled. He says, "I am not a real Indian... Because growing up in different times, I naively thought that Indian was something we were, not something we did or had or were required to prove on demand. Listening to my mother's stories about Oklahoma, about brutally hard lives and dreams that cut across the fabric of every experience, I thought I was Indian."

Historic Struggles for Identity

Florida State anthropologist J. Anthony Paredes asks about the identity of very old native groups, like those from the "Early" and "Middle Archaic" periods or the pre-maize burial mound cultures. He wonders if a Mississippian high priest would have been any less amazed than us to see a Paleo-Indian hunter throwing a spear at a woolly mastodon. This question shows that native cultures have changed and evolved over thousands of years.

The question of "Indianness" was different in colonial times. It wasn't hard to join Native American tribes. Native Americans usually accepted people based on things they could learn, like language, proper behavior, social connections, and loyalty, not on their race. Non-Native captives were often adopted into society, like Mary Jemison. The "gauntlet" was a ceremony often misunderstood as torture. But in Native American society, it was a ritual way for captives to leave their European society and become a tribal member.

Since the mid-1800s, arguments and competition have happened both within and outside tribes as societies changed. In the early 1860s, novelist John Rollin Ridge led a group to Washington D.C. to try and get federal recognition for a "Southern Cherokee Nation." This group was against the leadership of Chief John Ross.

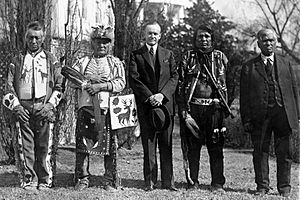

In 1911, Arthur C. Parker, Carlos Montezuma, and others started the Society of American Indians. This was the first national group founded and run mainly by Native Americans. The group worked for full citizenship for Native Americans and other changes. With different groups and people of various backgrounds involved, accusations that someone wasn't a "real Indian" were very hurtful. In 1918, Arapaho Cleaver Warden said in hearings about Native American religious ceremonies, "We only ask a fair and impartial trial by reasonable white people, not half-breeds who do not know a bit of their ancestors or kindred. A true Indian is one who helps for a race and not that secretary of the Society of American Indians."

In the 1920s, a famous court case looked into the identity of a woman called "Princess Chinquilla" and her friend Red Fox James. Chinquilla was a New York woman who claimed she was separated from her Cheyenne parents at birth. She and James created a club to be run by Native Americans, unlike other groups "founded by white people to help the red race." The club's opening was praised for being authentic, with a Council Fire, peace pipe, and speeches. In the 1920s, many clubs existed in New York, and titles like "princess" and "chief" were given to both Native and non-Native people. This allowed non-Natives to "try on" Native American identities.

Just as the fight for recognition isn't new, Native American businesses based on that recognition aren't new either. For example, the Creek Treaty of 1805 said that Creeks had the only right to run certain ferries and "houses of entertainment" along a federal road from Ocmulgee, Georgia to Mobile, Alabama. This road crossed parts of Creek Nation land.

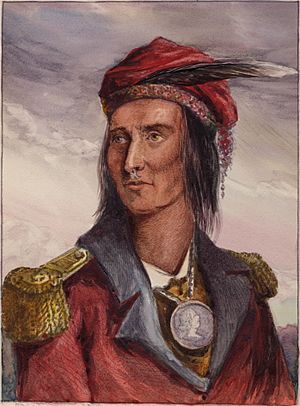

Unity and Native American Nationalism

The idea of "Indianness" grew in the 1960s with Native American nationalist movements like the American Indian Movement. This movement focused on a unified Native American identity, different from the "brotherhood of tribes" idea of groups like the National Indian Youth Council and the National Congress of American Indians. This unified identity was inspired by the teachings of 19th-century Shawnee leader Tecumseh, who wanted to unite all Native Americans against "white oppression." The movements of the 1960s greatly changed how Native Americans saw their identity: as separate from whites, as members of a tribe, and as part of a single group including all Native Americans.

Examples of Tribal Identity

Different tribes have their own unique cultures, histories, and situations that shape their identity. Tribal membership can be based on family descent, blood quantum, or living on a reservation.

Cherokee Identity

Historically, a person's race didn't decide if they were accepted into Cherokee society. The Cherokee people saw their identity as a political choice, not a racial one. For a long time, Cherokee society was like an Indian republic. Race and blood quantum are not factors for citizenship in the Cherokee Nation (like most Oklahoma tribes). To be a citizen, you need a direct Cherokee by blood or Cherokee freedmen ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls. Today, the tribe has members with African, Latino, Asian, white, and other ancestries. About 75% of tribal members have less than one-quarter Native American blood. The other two Cherokee tribes, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, do have a minimum blood quantum rule. Many Cherokee heritage groups exist in the Southeastern U.S..

Theda Perdue (2000) tells a story from before the American Revolution. A black slave named Molly was accepted as a Cherokee. She became a "replacement" for a woman killed by her white husband. In Cherokee tradition, revenge was needed for the woman's soul to find peace. The husband avoided execution by fleeing to the town of Chota (where he was safe by Cherokee law) and buying Molly as an exchange. When the wife's family accepted Molly, later known as "Chickaw," she became part of their clan (the Deer Clan) and thus Cherokee.

Inheritance was mostly through the mother's side, and clan membership was very important until about 1810. At that time, the seven Cherokee clans started to end blood vengeance by giving this sacred duty to the new Cherokee National government. Clans officially gave up their legal duties by the 1820s when the Cherokee Supreme Court was created. In 1825, the National Council gave citizenship to biracial children of Cherokee men. This broke the matrilineal (mother's side) definition of clans, and clan membership no longer defined Cherokee citizenship. These ideas were put into the 1827 Cherokee constitution. However, the constitution did say that "No person who is of negro or mulatlo [sic]parentage... shall be eligible to hold any office..." with an exception for "negroes and descendants of white and Indian men by negro women who may have been set free." Even though some Cherokee at this time thought clans were old-fashioned, this feeling might have been more common among leaders than the general population. So, even in their first constitution, the Cherokee kept the right to define who was and wasn't Cherokee as a political choice, not a racial one.

Most of the 158,633 Navajos counted in the 1980 census and the 219,198 Navajos in the 1990 census were enrolled in the Navajo Nation. The Navajo Nation has the largest number of enrolled citizens. It's interesting because only a small number of people who identify as Navajo are not registered.

Lumbee Identity

In 1952, Lumbee people, who were organized as Croatan Indians, voted to use the name "Lumbee" after the Lumber River near their homeland. The U.S. federal government recognized them as Indians in the 1956 Lumbee Act, but not as a fully federally recognized tribe. The Act did not give the tribe all the benefits of federal recognition.

Since then, the Lumbee people have tried to get Congress to pass laws for full federal recognition. Several federally recognized tribes have opposed their efforts.

When the Lumbee of North Carolina asked for recognition in 1974, many federally recognized tribes strongly opposed them. These tribes worried that recognizing the Lumbee would mean fewer services for historically recognized tribes. The Lumbee were once known by the state as the Cherokee Indians of Robeson County and applied for federal benefits under that name in the early 1900s. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians has been a main opponent of the Lumbee. It's sometimes noted that if the Lumbee gained full federal recognition, it would bring millions of dollars in federal benefits. It would also give them the chance to open a casino along Interstate 95, which would compete with a nearby Eastern Cherokee Nation casino.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |