Race (human categorization) facts for kids

Race is a way to group humans based on shared physical or social traits. These groups are usually seen as different within a certain society. The word "race" became common around the 1500s. Back then, it was used for different kinds of groups, including families. By the 1600s, it started to mean physical features. Later, it also referred to people from the same country.

Today, scientists see race as a social idea. This means it's an identity that society creates and assigns to people. Even though it's partly based on how people look, race doesn't have a true physical or biological meaning. The idea of race is a main part of racism. Racism is the belief that some human groups are better than others.

Ideas about race have changed over time. Scientists now believe that old ideas about race being a fixed biological thing are wrong. They generally don't use race to explain differences in how people look or act.

Most scientists agree that old ideas of race are not correct. However, some researchers still use the idea of race to talk about groups with similar traits. Others in the scientific community think the idea of race is too simple. Still others say that race has no real meaning for humans. This is because all living humans belong to the same subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens.

Since the mid-1900s, race has been linked to scientific racism, which has been proven wrong. The idea of race is now often seen as a false scientific way of grouping people. While still used in everyday talk, "race" is often replaced by clearer words. These include populations, people(s), ethnic groups, or communities. In 2023, the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine officially said that race should not be used in genetics.

Contents

What Is Race?

Today, experts see race as a social idea. This means race is not a natural part of humans. Instead, it's an identity created by groups, often powerful ones. They do this to make sense of society. Different cultures define racial groups in different ways. These definitions can also change over time.

- In South Africa, laws once recognized only White, Black, and Mixed-Race people.

- The government of Myanmar recognizes eight "major national ethnic races".

- Brazil's census groups people as White, Multiracial, Black, Asian, and Indigenous. But many people use other terms for themselves.

- The United States Census Bureau thought about adding a new group for Middle Eastern and North African people. But they decided not to.

Creating racial groups often led to treating some groups as less important. For example, in the 1800s United States, the "one-drop rule" said anyone with any African family history was considered "black". This was used to keep them out of the "white" group. Such racial ideas show the beliefs of powerful countries during the time of European colonization. This view means race is not defined by biology.

Some scientists, like geneticist David Reich, say that while race is a social idea, differences in family history that match racial groups are real. Other scientists disagree. They say that the meaning of these groups comes from social actions, not just genes.

Race often includes shared physical traits like skin color or hair. But this link is social, not biological. Racial groups can also share history, traditions, and language. For example, African-American English is spoken by many African Americans. This is especially true where racial separation still exists. Also, people often choose to identify with a race for political reasons.

When people define race, they create a social reality. This reality helps society group people. In this way, races are called social constructs. These ideas grow within different legal, economic, and social situations. Most experts agree that race has real effects on people's lives. This happens through set ways of favoring or discriminating against groups.

Old ideas about race, combined with money and social factors, have caused much suffering. Racial discrimination often comes with racist beliefs. This is when one group sees another group as racially different and morally worse. As a result, less powerful racial groups are often left out or treated badly. Racism has led to terrible events, like slavery and genocide.

In some countries, police use race to help find suspects. Many criticize this use of racial groups. They say it keeps old ideas about human differences alive and promotes stereotypes. Because racial groups often match patterns of social inequality, race can be an important factor for social scientists studying inequality.

Experts still debate how much racial groups are based on biology versus social ideas. For example, some focus on culture but also consider biology. Different fields of study use different ideas about race. Some focus more on biology, others more on social ideas.

In social studies, ideas like racial formation theory and critical race theory look at race as a social construct. They explore how ideas about race appear in daily life. Much research has shown how race has been used in laws and crime. This has led to certain groups being policed and jailed more often.

How Race Ideas Started

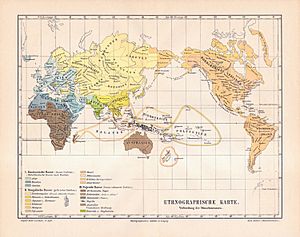

Humans have always seen themselves as different from other groups. But these differences were not always seen as natural, fixed, or worldwide. These are the key features of how we understand race today. The idea of race as we know it began during times of exploration and conquest. This brought Europeans into contact with people from other continents. It also came from the scientific idea of classifying things. The word race was often used in a general biological sense from the 1800s. It meant human populations that were genetically different based on how they looked.

The modern idea of race came from European countries exploring and taking over lands from the 1500s to 1700s. They defined race by skin color and physical differences. Some historians say ancient Greeks and Romans would have found these ideas confusing. Experts believe the modern idea of race was created and explained between 1730 and 1790.

Colonialism and Slavery

The European idea of "race" grew during the scientific revolution. This time focused on studying natural things. It also grew during the age of European imperialism and colonization. This led to new relationships between Europeans and people from other cultures. As Europeans met people from different parts of the world, they wondered about their physical and cultural differences. The rise of the Atlantic slave trade gave another reason to group humans. This helped them justify making African slaves serve them.

Europeans started to group themselves and others based on how they looked. They also linked certain behaviors and abilities to these groups. For example, the conflict between the English and Irish shaped early European ideas about differences. People began to believe that inherited physical differences were linked to inherited intelligence, behavior, and morals. Similar ideas existed in other cultures, like in China. There, a concept like "race" was linked to shared family history from the Yellow Emperor. This was used to show the unity of Chinese groups.

Early Ways to Classify People

The first published way to classify humans into races after ancient times was by François Bernier in 1684. In the 1700s, differences among human groups became a focus of science. But this scientific grouping of physical traits often came with racist ideas. These ideas always said that White Europeans had the best features. Other races were placed on a scale of less desirable traits.

In 1735, Carl Linnaeus, who created animal classification, divided humans into four types: European, Asian, American, and African. Each was linked to a different personality type. For example, Homo sapiens europaeus was called active and adventurous. Homo sapiens afer was called tricky, lazy, and careless.

In 1775, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach suggested five main groups: Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Ethiopian (later called Negroid), American Indian, and Malayan. But he did not say one race was better than another. Blumenbach also noted that appearances changed gradually from one group to the next. He said "you cannot mark out the limits between them."

From the 1600s to 1800s, common beliefs about group differences mixed with scientific ideas. This created what some call an "ideology of race." This idea said that races are original, natural, lasting, and distinct. It also said that some groups might be mixtures of older groups. But careful study could find the original races. Later classifications by Georges Buffon and others also called "Negros" less important than Europeans. In the United States, the ideas of Thomas Jefferson were important. He saw Africans as less smart than Whites. But he saw Native Americans as equal to Whites.

Different Ideas on Human Origins

In the late 1700s, the idea of polygenism became popular. This was the belief that different races evolved separately on each continent. It meant they did not share a common ancestor. This idea was supported by people like Edward Long and Charles White in England. In the US, Samuel George Morton and Louis Agassiz promoted this idea in the mid-1800s. Polygenism was very popular in the 1800s.

Modern Scientific Views

How Humans Evolved

Today, all humans are called Homo sapiens. But this is not the first human species. The first Homo species, Homo habilis, appeared in East Africa at least 2 million years ago. Members of this species quickly spread across Africa. Homo erectus evolved over 1.8 million years ago. By 1.5 million years ago, it had spread across Europe and Asia. Most physical anthropologists agree that Archaic Homo sapiens evolved from African Homo erectus. Anthropologists believe that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved in Africa. Then they moved out of Africa, mixing with and replacing other human groups in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Biological Classification

In the early 1900s, many anthropologists taught that race was fully biological. They believed it was key to a person's behavior and identity. This idea is called racial essentialism. This, along with beliefs that language, culture, and social groups were based on race, formed scientific racism. After the Nazi eugenics program and the rise of anti-colonial movements, racial essentialism lost popularity. New studies of culture and population genetics showed that racial essentialism was not scientifically sound. This led anthropologists to change their ideas about why people look different. Many modern anthropologists and biologists in the West now see race as not a real genetic or biological group.

Franz Boas was one of the first to challenge the idea of race. He showed that physical traits can change due to the environment. Ashley Montagu used evidence from genetics. E. O. Wilson also challenged the idea from the view of animal classification. He said that "races" were not the same as "subspecies."

Human genetic variation is mostly within groups, not between them. It also changes smoothly, which doesn't fit the idea of separate human races. According to anthropologist Jonathan Marks:

By the 1970s, it was clear that: (1) most human differences were cultural; (2) what wasn't cultural was mostly found in different groups at different rates; (3) what wasn't cultural or found at different rates changed gradually over geography; and (4) what was left was very small.

So, anthropologists and geneticists agreed that race, as people used to think of it (as separate, distinct groups of genes), did not exist.

Subspecies

The word race in biology is used carefully because it can be confusing. Usually, it means the same as subspecies. Subspecies are traditionally seen as groups that are separated by geography and are genetically different. Studies of human genetic variation show that human groups are not separated by geography. Their genetic differences are much smaller than those among comparable subspecies.

In 1978, Sewall Wright suggested that human groups living in separate parts of the world could be called different subspecies. This would be true if most people from these groups could be correctly identified just by looking at them. Wright said, "You don't need a trained anthropologist to classify English, West Africans, and Chinese with 100% accuracy by features, skin color, and hair type." This is true even though there is much variety within each group. While subspecies are often defined by easy-to-see physical looks, these differences don't always have an evolutionary meaning. So, this way of classifying has become less accepted by scientists who study evolution. This old-fashioned way of thinking about race is generally seen as wrong by biologists and anthropologists.

Gradual Changes (Clines)

A key idea in understanding human differences came from anthropologist C. Loring Brace. He observed that variations in genes and physical traits, caused by natural selection, slow migration, or genetic drift, are spread out along geographic gradients. These are called clines. For example, Brace wrote about skin color in Europe and Africa:

To this day, skin color changes gradually from Europe southward around the eastern Mediterranean and up the Nile into Africa. From one end to the other, there is no clear skin color boundary. Yet, the range goes from the lightest in the world in the north to the darkest possible for humans at the equator.

This shows a problem with defining races based on looks. It ignores other similarities and differences, like blood type, that don't match skin color. So, anthropologist Frank Livingstone said, "there are no races, only clines." This means differences are gradual, not in separate groups.

Theodore Dobzhansky agreed that if races have to be "separate units," then they don't exist. He also said that if "race" is used to "explain" human differences, it's wrong. He argued that the term race could be used if one separated "race differences" from "the race concept." The first means any difference in gene frequencies between groups. The second is "a matter of judgment." He noted that even with gradual changes, "Race differences are real biological things." But it doesn't mean that different groups must be given racial labels. In short, Livingstone and Dobzhansky agreed that there are genetic differences among humans. They also agreed that how race is used to classify people is a social choice. They disagreed on whether the idea of race is still useful.

In 1964, biologists Paul Ehrlich and Holm showed cases where two or more clines don't match. For example, melanin (which causes skin color) decreases as you go north or south from the equator. But the gene for sickle cell disease spreads out from specific points in Africa. As anthropologists Leonard Lieberman and Fatimah Linda Jackson noted, "Different patterns of differences prove that you can't describe a group as if it were genetically or even physically the same."

These patterns in human physical and genetic differences mean that the number and location of any described races depend on which traits are considered important. A gene change that lightens skin, thought to happen 20,000 to 50,000 years ago, partly explains light skin in people who moved out of Africa to Europe. East Asians have light skin due to different gene changes. However, the more traits or genes you look at, the more human subgroups you find. This is because traits and gene frequencies don't always match the same places. As Ossorio and Duster (2005) said:

Anthropologists found long ago that human physical traits change gradually. Groups that live close together are more similar than groups far apart. This pattern, called clinal variation, is also seen for many genes. Another finding is that traits or genes don't change at the same rate. This is called nonconcordant variation. Because physical traits vary gradually and don't match up, anthropologists in the late 1800s and early 1900s found that the more traits and groups they measured, the fewer clear differences they saw between races. They had to create more and more categories. The number of races grew until the 1930s and 1950s. Eventually, anthropologists concluded that there were no clear races. Scientists today find the same thing when looking at genes. Nature has not created four or five distinct, separate genetic groups of people.

Genetically Different Populations

Another way to look at differences is to measure genetic differences instead of physical ones. In the mid-1900s, anthropologist William C. Boyd defined race as: "A group that differs a lot from other groups in how often it has one or more of its genes." He said it was up to us which genes we chose to look at. Leonard Lieberman and Rodney Kirk pointed out that if one gene can define a race, then there are as many races as human couples. Also, anthropologist Stephen Molnar suggested that different clines mean there would be too many races, making the idea useless. The Human Genome Project says, "People who have lived in the same area for many generations may share some genes. But no gene will be found in all members of one group and in no members of any other."

Some biologists argue that racial groups match biological traits, like how people look. They say certain genetic markers are found at different rates among human groups. Some of these match traditional racial groupings.

How Genetic Variation Is Spread Out

It's hard to describe how genetic differences are spread within and among human groups. This is because it's hard to define a group, differences are gradual, and genes vary across the body. However, on average, 85% of genetic variation is within local groups. About 7% is between local groups on the same continent. About 8% is between large groups on different continents. The recent African origin theory for humans predicts that Africa has much more diversity than other places. It also predicts that diversity should decrease the further a group is from Africa. So, the 85% average figure can be misleading. Long and Kittles found that about 100% of human genetic diversity is in one African group. But only about 60% of human genetic diversity is in the least diverse group they studied. Statistical analysis confirms that "Western racial classifications have no scientific meaning."

Genetic Clusters and Gradual Changes

Recent studies of human genetic groups have debated how genetic variation is organized. The main ideas are clusters (groups) and clines (gradual changes). Some argue for smooth, gradual genetic variation in older groups. They say that any apparent gaps are just because of how samples were taken. Others disagree. They showed that there were small breaks in the smooth genetic variation where there were geographic barriers like the Sahara or the Himalayas. Still, they said their findings "should not be taken as support for any idea of biological race." They noted that genetic differences come mostly from gradual changes in gene frequencies, not from clear "diagnostic" genetic types. One study looked at 40 groups across the Earth. It found that "genetic diversity is spread in a more gradual pattern when more groups in between are sampled."

Guido Barbujani wrote that human genetic variation is generally spread continuously across much of Earth. He said there is no proof that clear genetic boundaries exist between human groups, which would be needed for human races to exist. Over time, human genetic variation has formed a layered structure. This doesn't fit the idea of races that evolved separately.

Race as a Social Idea

As anthropologists and other scientists moved away from using "race" to talk about genetic differences, historians, cultural anthropologists, and other social scientists started to see "race" as a cultural category or identity. This means it's one of many ways a society chooses to group its members.

Many social scientists now use the word "ethnicity" instead of race. Ethnicity refers to groups that identify themselves based on shared culture, family history, and past events. After Second World War, scientists became very aware of how beliefs about race had been used to justify unfair treatment, apartheid, slavery, and genocide. This questioning grew in the 1960s during the civil rights movement in the United States. It also grew as many countries around the world fought for independence. They came to believe that race itself is a social construct. This means it was believed to be real because of its social uses, not because it was an objective truth.

In 2000, Craig Venter and Francis Collins announced the mapping of the human genome. Venter realized that human genetic variation is small (1–3%). But the types of variations do not support the idea of genetically defined races. Venter said, "Race is a social idea. It's not scientific. There are no clear lines if we could compare all human genomes." He added, "When we try to use science to sort out these social differences, it all falls apart."

Anthropologist Stephan Palmié said that race "is not a thing but a social relationship." As such, the use of the word "race" itself needs to be looked at. They argue that biology won't explain why or how people use the idea of race. Only history and social relationships will.

Imani Perry said that race "is created by social arrangements and political choices." She added that "race is something that happens, rather than something that is. It changes, but it holds no objective truth." Similarly, Richard T. Ford (2005) argued that while there's no fixed link between race and culture, social practices can force people to act out "prewritten racial scripts."

Brazil

Compared to the United States in the 1800s, Brazil in the 1900s had less clear racial groups. According to anthropologist Marvin Harris, this shows a different history and different social relations.

Race in Brazil was seen as "biological," but in a way that recognized the difference between family history (genes) and physical differences (looks). In Brazil, racial identity was not set by strict rules, like the one-drop rule in the United States. A Brazilian child was not automatically given the race of one or both parents. There were also many more categories to choose from. So, even full siblings could be seen as different races.

Over a dozen racial categories could be recognized. These were based on all possible mixes of hair color, hair texture, eye color, and skin color. These types blended into each other like colors in a rainbow. No single category was clearly separate. This means race mostly referred to how someone looked, not their family history. And looks are not a good sign of family history. This is because only a few genes control skin color and traits. A person seen as white might have more African family history than a person seen as black. The opposite can also be true about European family history. The many racial groups in Brazil show how much genetic mixing happened in Brazilian society. This society is still very much grouped by color, but not strictly. These social and economic factors also affect racial lines. A small number of pardos, or brown people, might start calling themselves white or black if they move up in society. They might also be seen as "whiter" as their social status goes up.

European Union

The Council of the European Union states:

The European Union rejects ideas that try to say there are separate human races.

The European Union uses "racial origin" and "ethnic origin" to mean the same thing in its papers. It says that using "racial origin" in its rules does not mean it accepts such theories. Haney López warns that using "race" in law tends to make people believe it's real. In Europe, ethnicity and ethnic origin are perhaps more meaningful. They also don't carry the negative history linked to "race." In Europe, the history of "race" highlights its problems. In some countries, it is strongly linked to laws made by Nazi and Fascist governments in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1996, the European Parliament said that "the term should therefore be avoided in all official texts."

The idea of racial origin relies on the belief that humans can be separated into biologically distinct "races." Scientists generally reject this idea. Since all humans belong to the same species, the ECRI (European Commission against Racism and Intolerance) rejects theories based on different "races." However, the ECRI uses this term to make sure that people who are wrongly seen as belonging to "another race" are still protected by law. The law says it rejects the idea of "race," but it punishes situations where someone is treated unfairly because of it.

United States

People who came to the United States were from all over Europe, Africa, and Asia. They mixed with each other and with the native people of the continent. In the United States, most people who call themselves African American have some European family history. Many people who call themselves European American have some African or Native American family history.

Since the early history of the United States, Native Americans, African Americans, and European Americans were put into different racial groups. Efforts to track mixing led to many categories, like mulatto and octoroon. The rules for being in these races changed in the late 1800s. During the Reconstruction period, more Americans began to think that anyone with "one drop" of known "Black blood" was Black, no matter how they looked. By the early 1900s, this idea became law in many states. Amerindians continued to be defined by a certain percentage of "Indian blood" (called blood quantum). To be White, one had to have "pure" White family history. The one-drop rule meant that mixed-race people with any known African family history were called black. This rule was specific to those with African family history and to the United States.

The censuses taken every ten years since 1790 in the United States made it important to create racial categories and fit people into them.

The term "Hispanic" came about in the 1900s. This was when more workers from Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America moved to the United States. Today, "Latino" is often used to mean the same as "Hispanic." These terms are not about race. They include people who see themselves as different races (Black, White, Native American, Asian, and mixed groups). However, there's a common misunderstanding in the US that Hispanic/Latino is a race. Sometimes, people even think that national origins like Mexican or Cuban are races. In contrast, "Anglo" refers to non-Hispanic White Americans. Most of them speak English but are not necessarily of English descent.

Views on Race Over Time

Anthropology

The idea of race classification in physical anthropology lost trust around the 1960s. It is now seen as not correct. A 2019 statement by the American Association of Physical Anthropologists says:

Race does not show human biological variation accurately. It was never accurate in the past, and it's still inaccurate for today's human groups. Humans are not divided biologically into distinct continental types or racial genetic groups. Instead, the Western idea of race must be understood as a classification system that came from, and supported, European colonialism, unfair treatment, and discrimination.

A 2017 study surveyed 3,286 American anthropologists. They found that most agreed that biological races don't exist in humans. But they agreed that race does exist because social experiences of different racial groups can greatly affect health.

A 2003 study looked at how race was used in China's biological anthropology journal. It showed that Chinese anthropologists widely used the race concept. A 2007 review suggested that the difference between the US and China might be because race helps social unity in diverse China. In the US, "race" is a sensitive topic and is seen as hurting social unity.

A 2004 study looked at how anthropologists in different parts of the world accepted the idea of race. Rejection of race was highest in the United States and Canada. It was moderate in Europe, and lowest in Russia and China. This suggests that views on race are influenced by society and education.

A 2009 study surveyed European anthropologists' views on biological race. It found that those educated in Western Europe, physical anthropologists, and middle-aged people rejected race more often. This shows that views on race are influenced by society and education.

United States

Since the mid-1900s, physical anthropology in the United States has moved away from seeing human biological diversity as fixed types. Instead, it now focuses on genes and populations. Anthropologists tend to see race as a social way of classifying humans. This is based on how they look, their family history, and cultural factors. Since 1932, more and more college textbooks on physical anthropology have rejected race as a valid idea.

A 1998 "Statement on 'Race'" from the American Anthropological Association says:

In the United States, both experts and the public have been taught to see human races as natural and separate groups based on visible physical differences. But with much more scientific knowledge today, it's clear that human groups are not clear, distinct, biologically separate groups. Evidence from genetics (like DNA) shows that most physical variation, about 94%, is within so-called racial groups. Usual geographic "racial" groups differ from each other in only about 6% of their genes. This means there's more variation within "racial" groups than between them. In nearby groups, genes and their physical expressions overlap a lot. Throughout history, when different groups met, they mixed. This continued sharing of genetic material has kept all of humankind as a single species. [...]

Given what we know about how normal humans can achieve and function in any culture, we conclude that today's inequalities between so-called "racial" groups are not due to their biology. Instead, they are results of past and present social, economic, educational, and political situations.

An earlier survey in 1985 asked 1,200 American scientists if they disagreed with this idea: "There are biological races in the species Homo sapiens." Among anthropologists, 41% of physical anthropologists and 53% of cultural anthropologists disagreed. The same survey in 1999 showed that more anthropologists disagreed with the idea of biological race. The numbers were: 69% of physical anthropologists and 80% of cultural anthropologists.

Some, like forensic physical anthropologist George W. Gill, argue that race is real. He says that the idea that race is only skin deep "is simply not true, as any experienced forensic anthropologist will affirm." He adds that "Many physical features tend to follow geographic lines. This is not surprising since climate probably shaped human races. This includes not only skin color and hair, but also the bones of the nose and cheekbones." He believes that denying this evidence "seems to come from social and political reasons, not science."

In response to Gill, Professor C. Loring Brace says that experts can tell where someone's ancestors came from because biological traits are spread gradually across the planet. But this doesn't mean there are races. He states:

Well, you might ask, why can't we call those regional patterns "races"? We can and do, but it doesn't make them real biological groups. "Races" defined this way are products of what we see. ... We know that when we travel from Moscow to Nairobi, for example, there's a big but gradual change in skin color from what we call white to black. This is linked to how much sunlight there is. But we don't see the many other traits that are spread out in a way that has nothing to do with sunlight. For skin color, all northern groups in the Old World are lighter than people who have lived near the equator for a long time. Even though Europeans and Chinese are clearly different, their skin color is closer to each other than either is to people near the equator in Africa. But if we look at blood types, then Europeans and Africans are closer to each other than either is to Chinese.

The idea of "race" is still sometimes used in forensic anthropology (when studying bones), biomedical research, and race-based medicine. Brace has criticized forensic anthropologists for this. He argues they should talk about regional ancestry instead. He says that while they can tell if bones came from someone with African ancestors, calling those bones "black" is a social idea. It's only meaningful in the US and is not scientifically true.

Biology, Anatomy, and Medicine

In the same 1985 survey, 16% of biologists and 36% of developmental psychologists disagreed with the idea that "There are biological races in the species Homo sapiens."

The study's authors also looked at 77 biology and 69 physical anthropology textbooks from 1932 to 1989. Physical anthropology books said biological races existed until the 1970s. Then, they started saying races don't exist. Biology textbooks didn't change their view. Many just stopped talking about race altogether. The authors thought this was because biologists wanted to avoid the political issues of racial groups. They also wanted to avoid ongoing debates in biology about whether "subspecies" are real. The authors concluded, "The idea of race, which hides how similar all people are genetically and how differences don't match racial divisions, is not only bad for society but also biologically wrong."

In 2001, the editors of Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine asked authors not to use race and ethnicity unless there was a clear biological, scientific, or social reason. They said that using race and ethnicity had become an automatic habit. Nature Genetics now asks authors to explain why they use certain ethnic groups or populations and how they classified them.

A 2010 study of 18 common English anatomy textbooks found that they showed human biological variation in simple and old-fashioned ways. Many used the idea of race in ways that were common in the 1950s. The authors suggested that anatomy education should describe human differences in more detail. It should use newer research that shows how simple racial types are not enough.

A 2021 study looked at over 11,000 papers from 1949 to 2018 in the American Journal of Human Genetics. It found that "race" was used in only 5% of papers in the last decade. This was down from 22% in the first decade. Along with more use of "ethnicity," "ancestry," and location-based terms, it suggests that human geneticists have mostly stopped using the term "race."

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) officially said that "researchers should not use race as a stand-in for describing human genetic variation." Their report, released in March 2023, stated: "Classifying people by race is a practice linked to and based in racism."

Sociology

Lester Frank Ward (1841–1913), a founder of American sociology, rejected the idea that there were basic differences between races. But he knew that social conditions were very different by race. In the early 1900s, sociologists saw race based on the scientific racism of the 1800s and early 1900s. Many focused on African Americans, then called Negroes. They claimed they were less important than whites. For example, white sociologist Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935) used biological ideas to claim African Americans were inferior. American sociologist Charles H. Cooley (1864–1929) thought that differences among races were "natural." He believed biological differences led to differences in intelligence. Edward Alsworth Ross (1866–1951), another important figure in American sociology, believed whites were the best race. He thought there were basic differences in "temperament" among races. In 1910, a journal article called for white supremacy and separation of races to protect racial purity.

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), one of the first African-American sociologists, was the first to use sociology to study race as a social idea, not a biological one. Starting in 1899 with his book The Philadelphia Negro, Du Bois studied and wrote about race and racism throughout his career. He argued that social class, colonialism, and capitalism shaped ideas about race and racial groups. Social scientists mostly stopped using scientific racism and biological reasons for racial groups by the 1930s. Other early sociologists, especially those linked to the Chicago School, joined Du Bois in seeing race as a socially created fact. By 1978, William Julius Wilson argued that race and racial classification systems were becoming less important. He said that social class better described what sociologists once called race. By 1986, sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant successfully introduced the idea of racial formation. This describes how racial categories are created. Omi and Winant state that "there is no biological basis for telling human groups apart by race."

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, a Sociology professor, says, "I believe that racism is, more than anything else, about group power. It's about a main racial group (whites) trying to keep its advantages. And minorities fighting to change the racial situation." The types of actions under this new "color-blind racism" are subtle, built into systems, and supposedly not racial. Color-blind racism grows on the idea that race is no longer a problem in the United States. There are conflicts between the supposed color-blindness of most whites and the ongoing system of inequality based on color.

Today, sociologists generally see race and racial categories as socially created. They reject racial grouping ideas that depend on biological differences.

How Race Is Used in Practice

Medicine

In the United States, government policy encourages using racial data. This helps find and fix health differences between racial or ethnic groups. In hospitals, race has sometimes been used to help diagnose and treat medical conditions. Doctors have noticed that some conditions are more common in certain racial or ethnic groups. They are not always sure why. Recent interest in race-based medicine has grown with more human genetic data. This came after the human genome was mapped. There is a debate among medical researchers about the meaning and importance of race in their work. Those who support using racial categories say it helps apply new genetic findings and gives clues for diagnosis.

Other researchers point out that finding a difference in disease between two social groups doesn't mean genes caused the difference. They suggest that medical practices should focus on the individual, not their group. They argue that focusing too much on genes for health differences has risks. These include making stereotypes stronger, promoting racism, or ignoring other factors that affect health. International health data show that living conditions, not race, make the biggest difference in health outcomes. This is true even for diseases that have "race-specific" treatments. Some studies found that patients don't want to be racially categorized in medical care.

Law Enforcement

To help law enforcement officers find suspects, the United States FBI uses the term "race." This summarizes the general look of people they are trying to find. This includes skin color, hair type, eye shape, and other easy-to-notice features. For police, it's usually more important to have a description that quickly suggests how someone looks. It's less important to have a scientifically perfect classification by DNA. So, besides a racial category, a description will include height, weight, eye color, scars, and other unique features.

In many countries, like France, the government is legally not allowed to keep data based on race.

In the United States, racial profiling (using race to decide who to stop or question) has been ruled unconstitutional and a violation of civil rights. There is a debate about why there's a clear link between recorded crimes, punishments, and the country's populations. Many see de facto racial profiling as an example of institutional racism in law enforcement.

Mass incarceration in the United States affects African American and Latino communities much more. Michelle Alexander (2010) argues that mass incarceration is more than just crowded prisons. It's also "the larger web of laws, rules, policies, and customs that control those labeled criminals both in and out of prison." She says it's "a system that locks people not only behind actual bars in actual prisons, but also behind virtual bars and virtual walls." This shows the second-class citizenship given to many people of color, especially African Americans. She compares mass incarceration to Jim Crow laws, saying both act as racial caste systems.

Recent work using DNA to find race background has been used by some criminal investigators. This helps them narrow their search for suspects and victims. Supporters of DNA profiling say it has been useful. But the practice is still debated among medical ethicists, defense lawyers, and some in law enforcement.

The Constitution of Australia mentions 'people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws'. But there is no agreed definition of race in the document.

Forensic Anthropology

Similarly, forensic anthropologists use inherited physical features of human remains (like skull measurements). This helps them identify bodies, including their race. In a 1992 article, anthropologist Norman Sauer noted that anthropologists had generally stopped using race as a true way to describe human biological diversity. But forensic anthropologists still used it. He asked, "If races don't exist, why are forensic anthropologists so good at identifying them?" He concluded:

[T]he successful assignment of race to a skeletal specimen is not proof that the race concept is right. Instead, it's a prediction that an individual, when alive, was put into a certain socially created "racial" category. A specimen might show features that point to African family history. In this country, that person was likely called Black, whether or not such a race truly exists in nature.

Identifying someone's ancestry depends on knowing how often physical traits appear in a group. This doesn't require using a racial classification system based on unrelated traits. However, the idea of race is widely used in medical and legal settings in the United States. Some studies have reported that races can be identified very accurately using certain methods. But this method sometimes doesn't work in other times and places. For example, when the method was re-tested to identify Native Americans, the accuracy dropped from 85% to 33%. Knowing other information about the person (like census data) is also important for correctly identifying their "race."

In a different view, anthropologist C. Loring Brace said:

The simple answer is that, as members of the society that asks the question, they are taught the social rules that determine the expected answer. They should also know the biological mistakes in that "politically correct" answer. Bone analysis doesn't directly tell skin color. But it can accurately guess where someone's ancestors came from. African, East Asian, and European ancestry can be told with high accuracy. Africa, of course, means "black," but "black" doesn't always mean African.

In 2000, he wrote an essay against using the term "race."

A 2002 study found that about 13% of human skull measurement differences were between regions. 6% were between local groups within regions. And 81% were within local groups. In contrast, skin color (often used to define race) showed the opposite pattern. 88% of its variation was between regions. The study concluded that "The way genetic diversity is spread in skin color is unusual. It cannot be used for classification." Similarly, a 2009 study found that skull measurements could accurately tell what part of the world someone was from. However, this study also found no sudden boundaries that separated skull differences into distinct racial groups. Another 2009 study showed that American blacks and whites had different bone shapes. It also showed that there were significant patterns of variation in these traits within continents. This suggests that classifying humans into races based on bones would need many different "races" to be defined.

See also

In Spanish: Raza (clasificación de los seres humanos) para niños

In Spanish: Raza (clasificación de los seres humanos) para niños

- Biological anthropology

- Clan

- Cultural identity

- Environmental racism

- Interracial marriage

- Melanism

- Multiracial

- Nationalism

- Nomen dubium – a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

- Racism

- Races of Mankind for the Field Museum of Natural History exhibition by sculptor Malvina Hoffman

- All pages beginning with Racial

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |