Percy Grainger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Percy Grainger

Australian composer |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 8 July 1882 |

| Died | 20 February 1961 (aged 78) |

| Signature | |

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; July 8, 1882 – February 20, 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger, and pianist. He moved to the United States in 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. During his long and creative career, he helped bring back interest in British folk music in the early 1900s. While he wrote many experimental pieces, he is best known for his piano version of the folk dance tune "Country Gardens".

At 13, Percy left Australia to study music in Frankfurt, Germany. From 1901 to 1914, he lived in London. There, he became a well-known pianist, composer, and collector of folk songs. He met famous musicians like Frederick Delius and Edvard Grieg, becoming good friends with them. He loved music and culture from Nordic countries.

In 1914, Grainger moved to the United States and lived there for the rest of his life. He traveled often to Europe and Australia. He served briefly in the United States Army during World War I from 1917 to 1918. After his mother passed away in 1922, he became more involved in teaching music. He also experimented with music machines, hoping they could play music better than humans. In the 1930s, he created the Grainger Museum in Melbourne, his birthplace. This museum was a tribute to his life and works, and a place for future research. As he got older, he continued to perform concerts and rework his old songs. He wrote little new music. After World War II, his health declined, and he felt his career was not a success. He gave his last concert in 1960, less than a year before he died.

Contents

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

Family and Childhood

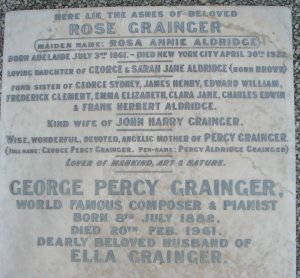

Percy Grainger was born on July 8, 1882, in Brighton, near Melbourne, Australia. His father, John Grainger, was an English architect. He designed the Princes Bridge in Melbourne. Percy's mother, Rose Annie Aldridge, was the daughter of a hotel owner.

John Grainger was a talented artist with many cultural interests. He knew many people, including David Mitchell. Mitchell's daughter, Helen, later became the famous opera singer Nellie Melba. The Graingers lived together until 1890. Then, John went to England for medical care. After he returned, they lived apart. Rose raised Percy, while John worked as an architect.

Percy was mostly taught at home, except for three months of school when he was 12. His mother, Rose, taught him music and literature. Other teachers helped him with languages, art, and drama. From a young age, Percy loved Nordic culture. He later said that the Icelandic Saga of Grettir the Strong greatly influenced his life.

He showed amazing musical talent early on. He also had a gift for art. Some of his teachers thought he might become an artist instead of a musician. At age 10, he began piano lessons with Louis Pabst, a top piano teacher in Melbourne. Percy's first known song, "A Birthday Gift to Mother," was written in 1893.

Pabst arranged Percy's first public concerts in Melbourne in July and September 1894. The young boy played pieces by Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, and Scarlatti. The Melbourne newspapers praised his performances.

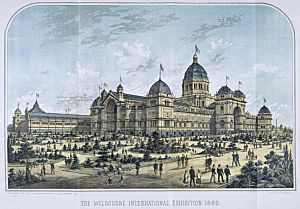

After Pabst left for Europe, Percy's new piano teacher, Adelaide Burkitt, arranged more concerts. These were in October 1894 at Melbourne's Royal Exhibition Building. The huge size of the venue scared the young pianist. Still, his performance impressed the critics. They called him "the flaxen-haired phenomenon who plays like a master."

This public success helped Rose decide that Percy should study at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, Germany. This school was recommended by William Laver, a piano teacher in Melbourne. Money for their trip was raised through a benefit concert in Melbourne and a final show in Adelaide. Mother and son left Australia for Europe on May 29, 1895. Percy never lived in Australia permanently again. However, he always felt proud of his Australian heritage.

Studying in Frankfurt

In Frankfurt, Rose taught English to earn money. John Grainger, who had moved to Perth, also sent money. The Hoch Conservatory was famous for piano teaching. Percy's piano teacher, James Kwast, quickly improved his skills. Within a year, Percy was seen as a musical genius.

Percy had trouble with his first composition teacher, Iwan Knorr. He left Knorr's classes to study privately with Karl Klimsch. Klimsch was an amateur composer and loved folk music. Percy later called him "my only composition teacher."

Percy and a group of older British students formed the Frankfurt Group. These friends included Roger Quilter, Balfour Gardiner, Cyril Scott, and Norman O'Neill. Their goal was to save British and Scandinavian music. They felt it was negatively influenced by central European music. Klimsch encouraged Percy to stop writing classical-style pieces. Instead, Percy developed his own unique style. His friends were amazed by how original and mature his music was.

During this time, Percy discovered the poems of Rudyard Kipling. He began setting them to music. According to Cyril Scott, "No poet and composer have been so suitably wedded since Heine and Schumann."

In the summer of 1900, Rose and Percy went on a long tour of Europe. Rose's health had been poor, and she had a nervous breakdown. She could no longer work. To earn money, Percy started giving piano lessons and public concerts. His first solo concert was in Frankfurt on December 6, 1900. He continued studying with Kwast and learned many new pieces. He felt confident he could support himself and his mother as a concert pianist. In May 1901, Percy decided to move to London. He left Frankfurt with Rose for the UK.

London Years and Growing Fame

Becoming a Concert Pianist

In London, Percy's charm, good looks, and talent helped him quickly find wealthy supporters. He soon performed at concerts in private homes. The Times newspaper said his playing showed "rare intelligence and a good deal of artistic insight." In 1902, he met Queen Alexandra. She often attended his London concerts after that.

In February 1902, Percy played as a piano soloist with an orchestra for the first time. He performed Tchaikovsky's first piano concerto. In October, he toured Britain with Adelina Patti, a famous opera singer. Patti was very impressed with Percy and predicted a great career for him.

The next year, he met the composer and pianist Ferruccio Busoni. They got along well at first. Busoni even offered to teach Percy for free. Percy spent part of the summer of 1903 in Berlin as Busoni's student. However, the visit did not go well. Busoni expected Percy to be a "willing slave," which Percy refused to be. Percy returned to London in July 1903. Soon after, he and Rose left for a 10-month tour of Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. He was part of a group organized by the Australian singer Ada Crossley.

A New Composer Emerges

Before London, Percy had written many Kipling songs and his first orchestral pieces. In London, he continued to compose when he had time. In July 1901, he wrote that he was working on his Marching Song of Democracy. He was also making good progress on experimental works like Train Music and Charging Irishrey. In his early London years, he also wrote Hill Song Number 1 (1902). Busoni greatly admired this instrumental piece.

In 1905, Percy was inspired by a talk from Lucy Broadwood, a folk-song historian. He began collecting original folk songs. He started in Brigg in Lincolnshire. Over the next five years, he collected and wrote down over 300 songs from all over the country. Much of this music had never been written down before. From 1906, Percy used a phonograph, one of the first collectors to do so. He made over 200 Edison cylinder recordings of folk singers. These activities happened during a time known as "the halcyon days of the 'First English Folksong Revival'."

As his fame grew, Percy met many leading musicians. These included Vaughan Williams, Elgar, Richard Strauss, and Debussy. In 1907, he met Frederick Delius. They immediately connected. Both musicians had similar ideas about music and harmony. They also disliked the traditional German masters. Both were inspired by folk music. Percy gave Delius his version of the folk song Brigg Fair. Delius turned it into his famous orchestral piece, which he dedicated to Percy. They remained close friends until Delius's death in 1934.

Percy first met Edvard Grieg in May 1906 in London. As a student, Percy had learned to appreciate Grieg's unique harmonies. By 1906, Percy played several of Grieg's pieces in his concerts, including the piano concerto. Grieg was very impressed with Percy's playing. He wrote: "I have written Norwegian Peasant Dances that no one in my country can play, and here comes this Australian who plays them as they ought to be played! He is a genius that we Scandinavians cannot do other than love."

During 1906–07, they wrote many kind letters to each other. This led to Percy's ten-day visit in July 1907 to Grieg's home, "Troldhaugen," near Bergen, Norway. They spent much time revising and practicing the piano concerto. This was for the Leeds Festival that year. Plans for a long working relationship ended with Grieg's sudden death in September 1907. Still, this short friendship greatly impacted Percy. He promoted Grieg's music for the rest of his life.

After a busy schedule of concerts in Britain and Europe, Percy went on a second tour of Australia and New Zealand in August 1908. During this trip, he added Maori and Polynesian music to his collection of recordings. He wanted to become a top pianist before promoting himself as a composer. However, he continued to write both original works and folk-song arrangements. Some of his most successful pieces, like "Mock Morris", "Handel in the Strand", "Shepherd's Hey", and "Molly on the Shore", come from this time. In 1908, he got the tune for "Country Gardens" from folk music expert Cecil Sharp. However, he didn't turn it into a full piece for another ten years.

In 1911, Percy finally felt confident enough to start publishing his compositions widely. At the same time, he began using "Percy Aldridge Grainger" as his professional name. In March 1912, five of his works were performed at London's Queen's Hall. The public loved them. A band of thirty guitars and mandolins for "Fathers and Daughters" made a special impression. On May 21, 1912, Percy gave his first concert entirely of his own music at the Aeolian Hall, London. He reported it was "a sensational success." His music received a similar warm welcome at another series of concerts the next year.

In 1905, Percy became close friends with Karen Holten, a Danish music student. She became an important confidante. Their friendship lasted eight years, mostly through letters. After she married in 1916, they continued to write and sometimes meet until her death in 1953. Percy was briefly engaged in 1913 to another student, Margot Harrison. But the relationship ended due to his mother's over-protectiveness and his own indecision.

Moving to America and Later Career

Life in the United States

In April 1914, Percy first performed Delius's piano concerto at a music festival. Thomas Beecham, a conductor at the festival, told Delius that Percy was good in loud parts but too noisy in quiet ones. Percy was getting more recognition as a composer. Leading musicians and orchestras were adding his works to their performances.

His decision to leave England for America in September 1914, after World War I began, hurt his reputation. His British friends, who were very patriotic, were upset. Percy wrote that he left "to give mother a change" because she had been unwell. However, others said he wanted to be Australia's first important composer and avoid being killed in the war. A music critic accused him of cowardice, which deeply hurt Percy.

Percy's first American tour started on February 11, 1915, with a concert in New York. He played works by Bach, Brahms, Handel, and Chopin. He also played two of his own songs: "Colonial Song" and "Mock Morris." In July 1915, Percy officially said he wanted to become a US citizen. Over the next two years, he played concerts with Nellie Melba. He also performed for President Woodrow Wilson. Besides concerts, he signed contracts to make pianola rolls and recordings.

In April 1917, Percy learned his father had died. On June 9, 1917, after America joined the war, he enlisted as a bandsman in the US Army. He joined the 15th Coast Artillery band as a saxophonist. He also learned to play the oboe. During his 18 months of service, Percy often played piano at Red Cross and Liberty bond concerts. As an encore, he started playing his piano version of "Country Gardens." This song became instantly popular. Its sheet music sales broke many records. The song became linked to Percy's name for the rest of his life, though he eventually disliked it. On June 3, 1918, he became an American citizen.

Peak of His Career

After leaving the army in January 1919, Percy turned down an offer to conduct the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. He went back to his career as a concert pianist. He soon performed about 120 concerts a year, usually to great praise. In April 1921, he reached more people by playing in a cinema, New York's Capitol Theatre. Percy said that the huge audiences at these cinema concerts often appreciated his playing more than those at famous places like Carnegie Hall. In the summer of 1919, he taught a piano course in Chicago. This was the first of many teaching jobs he would take later.

Between concerts and teaching, Percy found time to re-score many of his works. He did this throughout his life. He also wrote new pieces, like his Children's March: Over the Hills and Far Away. The orchestral version of The Power of Rome and the Christian Heart also came from this time. He began to develop elastic scoring, a way of arranging music that allowed different numbers and types of instruments to play his works. This meant small chamber groups or full orchestras could perform his music.

In April 1921, Percy moved with his mother to a large house in White Plains, New York. This house is now known as the Percy Grainger Home and Studio. It was his home for the rest of his life. From early 1922, Rose's health got much worse. She had delusions and nightmares. She feared her illness would harm her son's career. She died on April 30, 1922, while Percy was touring.

Between the World Wars

European Travels and New Ideas

After his mother's funeral, Percy found comfort in returning to work. In autumn 1922, he went on a year-long trip to Europe. He collected and recorded Danish folk songs. Then, he went on a concert tour to Norway, the Netherlands, Germany, and England. In Norway, he stayed with Delius at his summer home. Delius was almost blind by then. Percy helped him see a Norwegian sunset by carrying him (with some help) to the top of a nearby mountain. Percy returned to White Plains in August 1923.

Although he played fewer concerts each year, Percy remained a very popular performer. He had some unusual habits, often made bigger for publicity. For example, he sometimes ran into concert halls in gym clothes and leaped over the piano for a grand entrance. In 1924, Percy became a vegetarian, even though he disliked vegetables. His diet mainly included dairy, pastries, fruit, and nuts.

He continued to revise and re-score his own music. He also worked more on arranging music by other composers, especially Bach, Brahms, Fauré, and Delius. Outside of music, Percy was very interested in Nordic culture. He created a form of English that he believed showed the language's character before the Norman conquest. He replaced words of Norman or Latin origin with what he thought were Nordic forms. For example, he used "blend-band" for orchestra and "forthspeaker" for lecturer. He called this "blue-eyed" English.

Percy made more trips to Europe in 1925 and 1927. He collected more Danish folk music with the help of Evald Tang Kristensen, an old expert on cultures. This work became the basis for his Suite on Danish Folksongs (1928–30). He also visited Australia and New Zealand in 1924 and again in 1926.

Marriage and Teaching

In November 1926, while returning to America, Percy met Ella Ström. She was a Swedish artist, and they became close friends. They separated upon arriving in America but met again in England the next autumn. This was after Percy's last folk-song trip to Denmark. In October 1927, they decided to marry. Ella had a daughter, Elsie, born in 1909. Percy always treated Elsie as family and had a warm relationship with her.

The couple married on August 9, 1928, at the Hollywood Bowl. This was at the end of a concert that included the first performance of Percy's bridal song, "To a Nordic Princess," in honor of Ella.

From the late 1920s and early 1930s, Percy became more involved in teaching music. In late 1931, he accepted a year-long job as a music professor at New York University (NYU) for 1932–33. He gave a series of lectures called "A General Study of the Manifold Nature of Music." He introduced his students to many ancient and modern musical works. On October 25, 1932, Duke Ellington and his band performed to illustrate his lecture. Percy admired Ellington's music, seeing similarities with Delius.

Overall, Percy did not enjoy his time at NYU. He disliked the formal rules and found the university did not welcome his ideas. Despite many offers, he never accepted another formal teaching job. He also refused all offers of honorary degrees. His New York lectures became the basis for radio talks he gave for the Australian Broadcasting Commission in 1934–35. These were later published as Music: A Commonsense View of All Types. In 1937, Percy began working with the Interlochen National Music Camp. He taught regularly at its summer schools until 1944.

Music Innovation

Percy first thought of creating a Grainger Museum in Australia in 1932. He began collecting letters and items from friends. These included even very private things from his life. In September 1933, he and Ella went to Australia to start overseeing the building work. To pay for the museum, Percy gave many concerts and radio broadcasts. He showed his audiences a wide range of the world's music, following his "universalist" view. He controversially argued that Nordic composers were better than traditional masters like Mozart and Beethoven.

Among his new ideas, Percy introduced his "free-music" theories. He believed that following traditional rules of scales, rhythms, and harmony was like "absurd goose-stepping." He thought music should be free from these rules. He showed two experimental free music compositions. These were first played by a string quartet and later by electronic theremins. He believed that ideally, free music needed non-human performance. He spent much of his later life building machines to make this vision real.

While the museum was being built, the Graingers visited England for several months in 1936. During this time, Percy made his first BBC radio broadcast. In it, he conducted "Love Verses from The Song of Solomon." The singer was the then unknown Peter Pears. After spending 1937 in America, Percy returned to Melbourne in 1938 for the official opening of the Museum. His old piano teacher, Adelaide Burkitt, was there. The museum did not open to the public during Percy's lifetime. However, scholars could use it for research.

In the late 1930s, Percy spent much time arranging his works for wind bands. He wrote Lincolnshire Posy for a convention in 1937. In 1939, on his last visit to England before World War II, he composed "The Duke of Marlborough's Fanfare." He gave it the subtitle "British War Mood Grows."

Later Life and Legacy

World War II and After

When war broke out in Europe in September 1939, Percy's overseas travel stopped. In autumn 1940, he and Ella moved to Springfield, Missouri. They were worried the war might lead to an invasion of the US eastern coast. From 1940, Percy played regularly in charity concerts. This was especially true after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the war in December 1941. He made 274 charity appearances during the war years. Many were at Army and Air Force camps. In 1942, a collection of his Kipling songs, the Jungle Book cycle, was performed in eight cities.

Tired from his wartime concerts, Percy spent much of 1946 on holiday in Europe. He felt his career was a failure. In 1947, he refused a music professor job at Adelaide University. He wrote: "If I were 40 years younger, and not so crushed by defeat in every branch of music I have essayed, I am sure I would have welcomed such a chance." In January 1948, he conducted the first performance of his wind band version of The Power of Rome and the Christian Heart. He then criticized his own music as "commonplace."

On August 10, 1948, Percy appeared at the London Proms. He played the piano part in his Suite on Danish Folksongs. On September 18, he attended the Last Night of the Proms. He stood in the audience for Delius's Brigg Fair. Over the next few years, several friends passed away. In October 1953, Percy had surgery for abdominal cancer. He fought this disease for the rest of his life. He continued to perform concerts, often in church halls and schools rather than major venues.

In 1954, after his last Carnegie Hall appearance, Percy received the St. Olav Medal from King Haakon of Norway. This honored his long promotion of Grieg's music. But he became more bitter in his writings. He complained that "German form" music was still too popular. He said, "all my compositional life I have been a leader without followers."

After 1950, Percy almost stopped composing. His main creative work in his last ten years was with Burnett Cross. Cross was a young physics teacher. They worked on free music machines. The first was a simple device controlled by an adapted pianola. Next was the "Estey-reed tone-tool," a giant harmonica. Percy hoped it would be ready to play free music "in a few weeks." A third machine, the "Cross-Grainger Kangaroo-pouch," was finished by 1952. New transistor technology encouraged them to start a fourth, electronic machine. It was not finished when Percy died.

In September 1955, Percy made his final visit to Australia. He spent nine months organizing exhibits for the Grainger Museum. He refused a "Grainger Festival" suggested by the Australian Broadcasting Commission. He felt his homeland had rejected him and his music.

Final Years

By 1957, Percy's health had greatly declined. His ability to focus also lessened. Still, he continued to visit Britain regularly. In May of that year, he made his only television appearance. He played "Handel in the Strand" on the piano for a BBC program. Back home, after more surgery, he recovered enough for a small winter concert season. On his 1958 visit to England, he met Benjamin Britten. They had written friendly letters to each other before. Percy agreed to visit Britten's Aldeburgh Festival in 1959, but illness prevented him. Feeling that death was near, he made a new will. He wanted his skeleton preserved and possibly displayed in the Grainger Museum. This wish was not carried out.

Through the winter of 1959–60, Percy continued to perform his own music. He often traveled long distances by bus or train, as he would not fly. On April 29, 1960, he gave his last public concert at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. By then, his illness was affecting his concentration. His morning recital went well, but his conducting in the afternoon was, in his own words, "a fiasco." After this, he stayed home. He continued to revise his music and arrange others'. In August, he told Elsie he was working on an adaptation of one of Cyril Scott's early songs. His last letters, written from the hospital in December 1960 and January 1961, show him trying to work. He wrote despite failing eyesight and seeing things that weren't there: "I have been trying to write score for several days. But I have not succeeded yet."

Percy died in the White Plains hospital on February 20, 1961, at age 78. He was buried in the Aldridge family vault. His mother's ashes were also there. Ella, his wife, lived for 18 more years. In 1972, at 83, she married Stewart Manville, a young archivist. She died in White Plains on July 17, 1979.

Percy Grainger's Music

Percy Grainger's own works are in two groups: original songs and folk music arrangements. He also arranged many pieces by other composers. Even with his formal training, he went against traditional European music rules. He mostly avoided common forms like symphony, sonata, concerto, and opera. Most of his original songs are short, lasting two to eight minutes. Only a few started as piano pieces. However, he later made piano versions of almost all of them.

Conductor John Eliot Gardiner calls Percy "a true original" in how he used instruments. His short, clear style reminds some of 20th-century music and old Italian madrigals. Malcolm Gillies, a Grainger expert, says you know it's "Grainger" after hearing just one second of a piece. The most unique part of his music, Gillies says, is its texture. Percy described different textures as "smooth," "grained," and "prickly."

Percy believed in musical equality. He thought each player's role should be equally important. He created his elastic scoring technique so groups of any size and instrument mix could play his music well. He experimented in his earliest works. He used unusual rhythms with quick changes in time signature. This was in Love Verses from "The Song of Solomon" (1899) and Train Music (1901). This was long before Stravinsky did similar things.

To get specific sounds, Percy used unusual instruments and methods. These included solovoxes, theremins, marimbas, musical glasses, harmoniums, banjos, and ukuleles. In one early folk music concert, Quilter and Scott were asked to whistle parts. In "Random Round" (1912–14), Percy added an element of chance. Singers and players could choose variations randomly. This experiment in aleatoric music was decades before other composers used similar ideas.

The short "Sea Song" of 1907 was an early attempt by Percy to write "beatless" music. This piece, about 15 seconds long, was a step towards his free-music experiments of the 1930s. Percy wrote: "It seems to me absurd to live in an age of flying, and yet not be able to execute tonal glides and curves." He said the idea of tonal freedom had been in his head since he was a boy. He noticed the wave movements in the sea. He felt that music should be free like nature's sounds.

As a student, Percy learned to love Grieg's music. He saw Grieg as a perfect example of Nordic beauty. Grieg, in turn, called Percy a new direction for English music. He said Percy was "very original." After a lifetime of playing Grieg's works, Percy started adapting Grieg's E minor Piano Sonata in 1944. He called it a "Grieg-Grainger Symphony." But he stopped after writing only 16 bars. By this time, Percy felt he had not met Grieg's high expectations for him.

Percy was known for his musical experiments. He used the orchestra in new ways. One ambitious work was The Warriors (1913). This 18-minute orchestral piece was for an "Imaginary Ballet." He dedicated it to Delius. The music used parts of other Grainger works and ideas from other composers. It needed a huge orchestra and at least three pianos. In one performance, Percy used nineteen pianos with thirty pianists. Critics were unsure if the work was "magnificent" or just "a magnificent failure."

Percy Grainger's Legacy

Percy saw himself as an Australian composer. He said he wrote music "in the hopes of bringing honor and fame to my native land." However, he spent much of his career outside Australia. How much he influenced Australian music is still debated. His efforts to teach the Australian public in the mid-1930s were not well received. He didn't gain many followers there. In 2010, critic Roger Covell found only one important Australian musician, David Stanhope, working in Percy's style. In 1956, a suggestion to invite Percy to write music for the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne was rejected. A "Percy Grainger Festival" was held in London in 1970. It was organized by Australians living abroad and supported by the Australian government.

Percy was an atheist his whole life. He believed he would only live on through his body of work. To help this, he created the Grainger Museum in Melbourne. This museum received little attention before the mid-1970s. It was first seen as a sign of a huge ego or extreme oddness. Since then, the University of Melbourne has supported the museum. This has "rescued [it] permanently from academic denigration and belittlement." Its large collection of materials has been used to study Percy's life and works. It also helps study his friends like Grieg and Delius. The Grainger home in White Plains, New York, is now the Percy Grainger Library. It holds more items and historical performance materials for researchers and visitors.

In Britain, Percy's main legacy is bringing back interest in folk music. His pioneering work in recording and arranging folk songs greatly influenced the next generation of English composers. Benjamin Britten said Percy was his master in this area. After hearing some of Percy's folk song arrangements, Britten said they were better than others. In the United States, Percy left a strong educational legacy. He worked with high school, summer school, and college students for over 40 years. His new ways of using instruments have also influenced modern American band music. Timothy Reynish, a band conductor, called him "the only composer of stature to consider military bands the equal, if not the superior, in expressive potential to symphony orchestras." Percy's attempts to create "free music" using machines did not lead to further developments. New technologies quickly made his efforts outdated. However, Covell notes that Percy's determination and clever use of materials in this effort show a unique Australian side of his character. Percy would have been proud of this.

How Percy Grainger is Remembered

In 1945, Percy created his own informal rating system for composers and music styles. It was based on things like originality, complexity, and beauty. Out of forty composers and styles, he ranked himself ninth. He was behind Wagner and Delius, but well ahead of Grieg and Tchaikovsky. Still, in his later years, he often criticized his career. For example, he wrote to Scott: "I have never been a true musician or true artist."

He was frustrated that he was not recognized for his compositions beyond his popular folk-song arrangements. For years after his death, most of his music was not performed. Since the 1990s, more recordings of Percy's music have been made. This has brought new interest in his works. It has also improved his reputation as a composer. A tribute published on the Gramophone website in February 2011 said that Percy was "unorthodox, original and deserves better than to be dismissed by the more snooty arbiters of musical taste."

About Percy the pianist, The New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg wrote that his unique style was expressed with "amazing skill, personality and vigor." The early excitement for his concerts faded in later years. Reviews of his performances during his last ten years were often harsh. However, Britten thought Percy's late recording of the Grieg concerto was "one of the noblest ever committed to record." This was despite the recording being kept from release for many years due to mistakes. Brian Allison from the Grainger Museum has wondered if Percy might be remembered as a leading Australian painter and designer today. This might have happened if his father's influence had not been removed.

Recordings of Percy Grainger's Music

Between 1908 and 1957, Percy made many recordings. He usually played piano or conducted his own music and others'. His first recordings included a part of Grieg's piano concerto. He did not record a full version of this work until 1945. Much of his recording work was done between 1917 and 1931. He had a contract with Columbia. At other times, he recorded for Decca (1944–45 and 1957) and Vanguard (1957).

Of his own compositions, "Country Gardens," "Shepherd's Hey," "Molly on the Shore," and "Lincolnshire Posy" were recorded most often. For other composers, he most often recorded piano works by Bach, Brahms, Chopin, Grieg, Liszt, and Schumann. All of Percy's early solo piano recordings are now available on CD.

From 1915 to 1932, Percy worked with the Duo-Art company. He made about 80 piano rolls of his own and others' music. These rolls were played by a wooden robot on a concert grand piano. Many of these rolls have since been recorded onto compact disc. This system allowed Percy to appear posthumously (after his death) at the Royal Albert Hall in London. In 1988, during the Last Night of the Proms, he was the soloist with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in Grieg's Piano Concerto.

Since Percy's death, many artists have recorded his works. Chandos Records began to create a complete recorded edition of Percy's original compositions and folk settings in 1995. Out of 25 planned volumes, 19 were finished by 2010. These were released as a CD box set in 2011 to mark 50 years since his death. A re-release with two extra CDs came out in January 2021 for his 60th death anniversary.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |