Piscataway people facts for kids

| Kinwaw Paskestikweya | |

|---|---|

The three Piscataway tribal leaders representing the Piscataway Indian Nation and Tayac Territory, Piscataway-Conoy Tribe of Maryland, and Cedarville Band of Piscataway received official recognition as tribes from the State of Maryland in 2012. Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley is 2nd from right.

|

|

| Total population | |

| est. 4,103 Piscataway Indian Nation 500 |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Nanticoke/Kinwaw Algic | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, big house religion. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mattawoman, Patuxent, Doeg, Nanticoke, Yaocomico |

The Piscataway are a group of Native American people. They once spoke the Piscataway language, which was part of the larger Algonquian language family. This language was a dialect of Nanticoke. Over time, after many years of contact with European settlers, their population greatly decreased. They eventually joined with a neighboring tribe called the Conoy.

Today, two main groups of Piscataway descendants are officially recognized as Native American tribes by the state of Maryland. These groups are the Piscataway Indian Nation and Tayac Territory and the Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland. The Piscataway Conoy Tribe includes the Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Sub-Tribes, and the Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians. All these groups live in Southern Maryland. However, they are not recognized by the United States federal government.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Piscataway people were known by many names to the English settlers. These names included Pascatowies, Paschatoway, and Pazaticans. They were also sometimes called by the names of their villages. Some of these villages were Moyaonce, Accokeek, and Potapaco.

Other tribes who spoke similar Algonquian languages were their neighbors. These included the Anacostan, Mattawoman, and Pamunkey. Tribes like the Nanticoke and Patuxent were also related, but a bit more distantly.

Piscataway Language and Communication

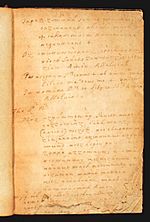

The Piscataway language belonged to the large Algonquian language family. In 1640, a Jesuit missionary named Father Andrew White translated the Catholic catechism into Piscataway. Other English missionaries also created materials in the Piscataway language. This helped people learn about their language.

Where the Piscataway Lived

Around the year 1600, the Piscataway lived mainly on the north side of the Potomac River. This area is now Charles, southern Prince George's, and parts of western St. Mary's counties in southern Maryland. This information comes from John Smith's map from 1608. Their land was covered in woods and had many waterways.

Some settlements along the Patuxent River were also under Piscataway influence. Piscataway settlements appeared in this same area on maps until the 1700s. Today, descendants of the Piscataway still live in parts of their traditional homeland. None of the three state-recognized tribes have a special land area called a reservation. This lack of land has made it harder for them to prove their history and gain federal recognition.

Piscataway Daily Life and Culture

The Piscataway people relied more on farming than many of their neighbors. This allowed them to live in permanent villages. They built their homes near waterways where they could use canoes.

Their main crops included corn, several types of beans, melons, pumpkins, and squash. Women were responsible for growing and harvesting these crops. Men hunted animals like bear, elk, deer, and wolves. They also hunted smaller animals such as beaver, squirrels, and wild turkeys. Fishing and gathering oysters and clams were also important food sources. Women also collected berries, nuts, and roots when they were in season.

Piscataway villages often had several houses. These houses were protected by a strong fence made of logs called a palisade. Traditional houses were rectangular, about 10 feet high and 20 feet long. They were a type of longhouse with rounded roofs. These roofs were covered with bark or woven mats. A fireplace was in the center of the house, with a smoke hole above it.

Piscataway History

Early Times: Before European Contact

Many different groups of indigenous peoples lived in the Chesapeake and Tidewater regions. Archeologists believe people arrived here between 3,000 and 10,000 years ago. The Algonquian people who would become the Piscataway nation lived in the Potomac River area since at least 1300 AD. Around 800 AD, people living along the Potomac started growing maize (corn). This corn added to their diet of fish, game, and wild plants.

Some clues suggest the Piscataway might have moved from the Eastern Shore of Maryland or from the upper Potomac River. However, by the 1500s, the Piscataway were a clear group with their own society and culture. They lived in permanent villages all year round.

After 1300, a "Little Ice Age" made the climate colder. This caused Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples to move south to the warmer Potomac basin. The growing seasons there were long enough for them to grow corn. As more tribes moved into the area, they competed for resources. This led to more conflicts.

By 1400, the Piscataway and their Algonquian neighbors grew in number. This was because of their advanced farming methods. They grew calorie-rich corn, beans, and squash. These crops created extra food, which helped support larger populations. Women grew and prepared many types of corn and other plants. The Piscataway and related groups could feed their growing communities. They also continued to gather wild plants from nearby marshes. The men cleared new fields, hunted, and fished.

The 1600s and English Settlers

By 1600, attacks by the Susquehannock and other Iroquoian peoples from the north had destroyed many Piscataway villages. These villages were located above present-day Great Falls, Virginia on the Potomac River. The villages below the falls survived by working together for defense. They slowly united under strong leaders called hereditary chiefs. These chiefs collected payments, sent men to war, and organized resistance against northern attacks. A system of villages and rulers developed. By the late 1500s, every chief on the north bank of the Potomac reported to the main chief. This main chief of the Piscataway was known as the Tayac.

The English explorer Captain John Smith first visited the upper Potomac River in 1608. He wrote about the Piscataway, calling them Moyaons. This was the name of their main village, where the Tayac lived. The Nacotchtank people, who lived near what is now Washington, DC, were closely connected to them. The Taux (Doeg) lived on the Virginia side of the river. Some rivals of the Tayac hoped the English newcomers would change the power balance in the region.

The Virginia Company and later the Virginia Colony often sided with enemies of the Piscataway. They wanted to trade for furs. Their arrival began to shift the power in the area. By the early 1630s, the Tayac's control over some of his smaller chiefs had weakened a lot.

However, when the English started to settle in what is now Maryland in 1634, the Tayac Kittamaquund made the newcomers his allies. He became Tayac that year after killing his brother, Wannas. He gave the English a former Indian settlement. The English renamed it St. Mary's City, Maryland after Queen Henrietta Marie.

The Tayac wanted this new English settlement to protect them from Susquehannock attacks from the north. Kittamaquund and his wife became Christians in 1640. This happened through their friendship with the English Jesuit missionary Father Andrew White. Their only daughter, Mary Kittamaquund, was cared for by the English governor and his sister-in-law, Margaret Brent. They made sure Mary learned English and received an education.

Mary Kittamaquund married the much older English colonist Giles Brent when she was young. After her father died, the couple tried to claim Piscataway land. They then moved south across the Potomac to set up a trading post. They lived at Aquia Creek in what is now Stafford County, Virginia. They are believed to have had three or four children. Giles Brent married again in 1654, so Mary may have died young.

The benefits of having the English as allies did not last long for the Piscataway. The Maryland Colony was too weak at first to be a big threat. But once the English colony grew stronger, they turned against the Piscataway. By 1668, the Algonquian people on the western shore were forced onto two reservations. One was on the Wicomico River, and the other was on part of the Piscataway homeland. People from other Algonquian nations who had lost their land joined the Piscataway.

Colonial leaders made the Piscataway allow the Susquehannock people to settle in their territory. The Susquehannock were an Iroquoian-speaking group. They had been defeated in 1675 by the Iroquois Confederacy from New York. These old enemies eventually fought openly in Maryland. With the tribes at war, the Maryland Colony forced the Susquehannock out after the Piscataway attacked them. The Susquehannock suffered a big defeat.

The surviving Susquehannock moved north and joined their former enemies, the Iroquois Confederacy. Together, these Iroquoian tribes repeatedly attacked the Piscataway. The English offered little help to their Piscataway allies. Instead of sending soldiers to help, the Maryland Colony continued to try and take control of Piscataway land.

The Piscataway's situation worsened as the English Maryland colony grew. They were especially affected by diseases, which greatly reduced their population. They also suffered from wars between tribes and with the colonists. After the English tried to remove tribes from their lands in 1680, the Piscataway fled. They moved away from the English settlers to Zekiah Swamp in Charles County, Maryland. There, they were attacked by the Iroquois, but peace was eventually made.

In 1697, the Piscataway moved across the Potomac River. They camped near what is now The Plains, Virginia. Settlers in Virginia were worried and tried to convince the Piscataway to return to Maryland, but they refused. Finally, in 1699, the Piscataway moved north. They settled on what is now called Conoy Island in the Potomac, near Point of Rocks, Maryland. They stayed there until after 1722.

The 1700s: Moving North

In the 1700s, the Maryland Colony canceled all Native American claims to their lands. They also closed the reservations. By the 1720s, some Piscataway and other Algonquian groups had moved to Pennsylvania. They settled just north of the Susquehanna River. These people from Maryland were called the Conoy and the Nanticoke. They spread along the western edge of the Pennsylvania Colony. Other groups like the Lenape, Tutelo, Shawnee, and some Iroquois also lived there. At that time, the Piscataway were said to number only about 150 people. They sought protection from the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. However, the Pennsylvania Colony also proved to be unsafe.

Most of the remaining tribe moved north in the late 1700s. They were last mentioned in historical records in 1793 in Detroit. This was after the American Revolutionary War, when the United States became independent. In 1793, a meeting in Detroit reported that these people had settled in Upper Canada. They joined other Native Americans who had supported the British during the war. Today, descendants of these northern migrants live on the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation reserve in Ontario, Canada.

Some Piscataway may have moved south towards the Virginia Colony. It is believed they joined with the Meherrin tribe.

The 1800s: Surviving in Their Homeland

Many historians and archaeologists have shown that a small group of Piscataway families continued to live in their homeland. Even though the larger tribe lost its independence, descendants of the Piscataway survived. They formed families with other people in the area, including European servants and free or enslaved Africans. They became rural farmers and were often listed as "free people of color". However, some kept their Native American cultural traditions. For many years, the United States census did not have separate categories for Native Americans. Especially in states where slavery existed, all free people of color were grouped together as black. This was due to the racial system of slavery.

In the late 1800s, archaeologists, journalists, and anthropologists interviewed many Maryland residents. These residents said they were descendants of tribes connected to the old Piscataway chiefdom. The Catholic Church was unique because it continued to identify Indian families in its records. These church records became very helpful for researchers. Anthropologists and sociologists called these self-identified Indians a "tri-racial" community. They were sometimes called "Wesorts", a name some found offensive.

In the 1800s, census takers often listed most Piscataway individuals as "free people of color" or "mulatto". This was because they had married people of African and European descent. The huge drop in Native American populations from disease and war, plus racial segregation due to slavery, led to a simple "black or white" view of race. However, Catholic church records in Maryland and some studies accepted that Piscataway people were still Indians, even with mixed ancestry. This strict division of society in the South grew after the American Civil War and the end of slavery. White Southerners tried to regain control and assert white supremacy.

Piscataway Revitalization: The 1900s and 2000s

By the early 1900s, only a few families identified as Piscataway. Strict racial attitudes and "Jim Crow" policies often classified minority groups as black. In the 1900s, states like Virginia passed laws that said anyone with any African ancestry was "black." For example, in Virginia, a man named Walter Plecker ordered records to be changed. This meant Indian families lost their official ethnic identity.

Phillip Sheridan Proctor, later known as Turkey Tayac, was born in 1895. He brought back the use of the title tayac, which he claimed was passed down to him. Turkey Tayac played a key role in bringing back American Indian culture. He helped Piscataway and other Indian descendants across the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast. He worked with the American Indian Movement to help with this revival.

Chief Turkey Tayac was an important leader in the cultural revival movements of the early and mid-1900s. His leadership inspired tribes beyond the Piscataway. Revival also happened among other Southeastern American Indian communities. These included the Lumbee, Nanticoke, and Powhatan tribes. Chief Turkey Tayac took on the traditional leadership title "tayac" when American Indian identity was being controlled by rules like "blood quantum". He organized a movement that focused on how American Indian peoples identified themselves.

There are still Indian people in southern Maryland. They live without a reservation near US 301 between La Plata and Brandywine. They are officially organized into several groups, all using the Piscataway name.

After Chief Turkey Tayac died in 1978, the Piscataway split into three groups:

- The Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes (PCCS)

- The Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians

- The Piscataway Indian Nation

These three groups have had disagreements. They have argued about seeking state and federal tribal recognition. They have also disagreed about building casinos if they gained recognition. And they have debated which groups were truly Piscataway.

Two organized Piscataway groups exist today:

- Piscataway Indian Nation and Tayac Territory, led by Billy Redwing Tayac, who is the son of the late Chief Turkey Tayac.

- Piscataway Conoy Tribe, which includes two parts:

- Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Sub-Tribes

- Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians, led by Natalie Proctor.

In the late 1990s, a Maryland state committee looked at many old records. This committee included a genealogist from the Maryland State Archives. They confirmed that some modern Piscataway families were indeed descendants of the historic Piscataway. New studies are now looking at how people identified themselves in the past. Unlike during the time of racial segregation, when anyone with African descent was called black, these studies focus on the history of different ethnic cultures and racial groups.

The State of Maryland created a group of experts to review old records about Piscataway family history. This group concluded that some people who identify as Piscataway today are descendants of the historic Piscataway.

In 1996, the Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs (MCIA) suggested giving state recognition to the Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes. Some people were concerned about businesses that supported the Piscataway Conoy. They worried about gambling interests. (Since the late 1900s, many recognized tribes have opened casinos to earn money.) Governor Parris Glendening, who was against gambling, denied the tribe's request.

In 2004, Governor Bob Ehrlich also denied the Piscataway Conoy's request for state recognition. He said they did not prove they were descendants of the historical Piscataway Indians, as required by state law. Throughout this effort, the Piscataway-Conoy stated they had no plans to build casinos.

In December 2011, the Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs said the Piscataway had provided enough historical documents. They recommended recognition. On January 9, 2012, Governor Martin O'Malley issued orders recognizing all three Piscataway groups as Native American tribes. As part of this agreement, the tribes promised not to start gambling businesses. The orders also state that the tribes do not have any special "gambling privileges."

Notable Piscataway People

- Mary Kittamaquund (born around 1634 – died around 1654/1700), she was the daughter of the tribal leader, Kittamaquund.

- Turkey Tayac (Phillip Sheridan Proctor) (1895–1978), a tribal leader and traditional herbal doctor.

- Gladys Proctor (Carrier of the Pipe) (1919-2018), she was the Clan Mother of the Wild Turkey Clan, Cedarville Band. She was a noted scholar of Piscataway history and culture. Her research helped gain tribal recognition in 2012.

- Delonte West, a retired NBA basketball player.

Images for kids

-

The three Piscataway tribal leaders representing the Piscataway Indian Nation and Tayac Territory, Piscataway-Conoy Tribe of Maryland, and Cedarville Band of Piscataway received official recognition as tribes from the State of Maryland in 2012. Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley is 2nd from right.

-

Catholic Catechism prayers written in Piscataway, Latin, and English by Andrew White, a Catholic missionary, around 1634–1640. This document is kept at Lauinger Library, Georgetown University.

See also

In Spanish: Piscataway para niños

In Spanish: Piscataway para niños