Royal Indian Navy mutiny facts for kids

The Royal Indian Navy Uprising, also known as the 1946 Naval Uprising, was a major event where Indian sailors, soldiers, police, and regular people protested against the British government in India. It started in Bombay (now Mumbai) and quickly spread across British India, from Karachi to Calcutta (now Kolkata). More than 20,000 sailors on 78 ships and at many shore bases joined in.

The uprising ended when the sailors surrendered to British officials. The Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League convinced the sailors to give up. They worried that such a large armed protest could cause problems right before India was about to become independent. Only the Communist Party of India supported the rebellion across the country.

The uprising began on February 18, 1946, as a strike by sailors of the Royal Indian Navy (RIN). They were protesting bad living conditions and poor food. By the evening of February 19, the sailors had elected a Naval Central Strike Committee. Many Indian people supported the strike, and there was even a one-day general strike in Bombay. The protests spread to other cities and were joined by parts of the Royal Indian Air Force and local police forces.

Indian naval personnel started calling themselves the "Indian National Navy." They even saluted British officers with their left hand as a sign of disrespect. In some places, Indian non-commissioned officers in the British Indian Army ignored orders from their British superiors. Riots happened from Karachi to Calcutta. Interestingly, the protesting ships flew three flags tied together: those of the Indian National Congress, the All-India Muslim League, and the Red Flag of the Communist Party of India. This showed that the sailors were united and put aside their religious differences.

The revolt ended after a meeting between M. S. Khan, the head of the Naval Central Strike Committee, and Vallabhbhai Patel from the Congress party. They were promised that no one would be punished. However, many sailors were arrested and held in difficult conditions later on. Patel and Muhammad Ali Jinnah (from the Muslim League) both asked the strikers to surrender. Under this pressure, the sailors gave up. Many were then arrested, had military trials, and 476 sailors were kicked out of the Royal Indian Navy. None of them were allowed to join the Indian or Pakistani navies after independence.

Quick facts for kids Royal Indian Navy rebellion |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

HMIS Hindustan near the shore. |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

|

||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

No centralised command |

|

||||

Contents

Why the Sailors Were Unhappy

During World War II, the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) grew very quickly. It went from a small group of ships to a large navy. This growth happened fast as the war changed. The navy got many different types of warships and landing boats. Its bases in British India also grew with better dockyards and new training places. The RIN helped stop Japanese forces in the Indian Ocean. They protected Allied ships, defended India's coast, and supported military operations.

Because of the war, people from all over India, and from different religions and backgrounds, joined the navy. Many were from villages and had never met British people before. High prices, famines, and other money problems forced many to join the British army. In just a few years, these new recruits changed their way of thinking. They learned about events happening around the world.

By 1945, the RIN was ten times bigger than it was in 1939. Between 1942 and 1945, leaders of the Communist Party of India even helped recruit Indians, especially communist activists, into the British Indian Army and RIN to fight against Nazi Germany. But once the war ended, these new recruits turned against the British government.

After the War: Demobilisation

When the war with Japan ended, the Royal Indian Navy started sending many sailors home. Ships that were rented were returned, and some naval bases were closed. Sailors were gathered in a few main bases to be released from service. Many were sent to naval bases in Bombay, which was the main RIN base. These bases became very crowded with bored and unhappy sailors waiting to go home.

The Indian sailors were unhappy for many reasons. Their living conditions were bad, they were treated unfairly, and their pay was not enough. They also felt that their senior leaders did not care about them. Even though the navy grew during the war, most of the officers were still British. The navy was known for having very few Indian officers. All these problems, combined with tensions between different races and the strong desire for India to be free, created a very tense situation in the navy.

Indian National Army Trials

Stories about the Indian National Army (INA) trials, and about Subhas Chandra Bose ("Netaji") and the INA's fight, became very popular. These stories, heard on the radio and in the news, made the sailors even more unhappy and inspired them to protest. After World War II, three INA officers were put on trial at the Red Fort in Delhi. They were accused of "waging war against the King Emperor," which meant fighting against the British King.

The British government believed that the Indian National Congress party's support during these trials, their election campaigns, and their talk about harsh actions during the Quit India Movement made people very angry. There were many protests between November 1945 and February 1946. In September 1945, the Congress party had decided that if there were any conflicts, they should try to talk and find a peaceful solution.

The city of Calcutta, in particular, saw many protests against the trials. This led to many people supporting the idea of a revolutionary, independent India, which was promoted by the Communist Party of India.

Unrest in British Forces in India

Between 1943 and 1945, the Royal Indian Navy had nine smaller protests on different ships.

In January 1946, British airmen in India also protested. This was called the Royal Air Force mutiny of 1946. They were mainly upset about how slowly they were being sent home. Some also protested against being used to stop India's independence movement. The British leader in India, Lord Wavell, said that the British airmen's actions had influenced the protests in both the Indian Air Force and Navy. He felt that the British airmen "got away with what was really a mutiny."

In early February 1946, protests also broke out in the Indian Army Pioneer Corps in Calcutta and later at a training center in Jubbulpore. According to Francis Tucker, a British commanding officer, unhappiness against British rule was growing fast among government workers, police, and even in the armed forces.

The Start at HMIS Talwar

HMIS Talwar was a naval base in Bombay with a signals school. After the war, many sailors were sent there. About 1,000 communications operators lived at the base. Most of them were from middle-class families and had some education, unlike other sailors who were mostly farmers. In late 1945, about 20 operators and some supporters, who were angry about racial discrimination, formed a secret group called Azad Hind (Free Indians). They started planning ways to challenge their senior officers.

The first incident happened on December 1, 1945. The RIN commanders planned to open the base to the public. That morning, the secret group vandalized the area. They littered the parade ground with burnt flags and put brooms and buckets on the tower. They also painted slogans like "Quit India" and "Revolt Now!" on the walls. The senior officers cleaned up before the public arrived and did not take further action. This weak response made the group bolder, and they continued similar activities for months.

The British Commander-in-Chief, Claude Auchinleck, had told officers to be somewhat tolerant. He wanted a smooth transition if India became independent, so British interests would be protected. Since they couldn't catch the plotters and couldn't take strict action, the leaders at HMIS Talwar tried to send sailors home faster. They hoped the troublemakers would leave the navy this way. As a result, the group became smaller, but the remaining members were even more eager for nationalistic actions.

On February 2, 1946, Auchinleck himself was supposed to visit the base. Officers had guards to prevent any large protests. But the group still managed to put stickers and paint slogans like "Quit India" and "Jai Hind" on the podium where he would stand. The vandalism was seen before sunrise. Balai Chandra Dutt, a five-year war veteran, was caught escaping with stickers and glue. His locker was searched, and they found communist and nationalist writings. This material was considered rebellious. Dutt was questioned by five senior officers, including a high-ranking admiral. He said he was responsible for all the vandalism and called himself a political prisoner. He was put in solitary confinement for seventeen days, but the protests continued even while he was imprisoned.

Some sailors complained about their commanding officer's leadership. On February 17, many sailors started refusing food and orders for military parades. The commanding officer, King, had reportedly called a group of sailors "black bastards." By February 18, sailors at HMIS Sutlej, HMIS Jumna, and at the Castle and Fort Barracks in Bombay Harbour also started refusing orders. They did this to support the operators at HMIS Talwar.

At 12:30 PM on February 18, 1946, it was reported that all sailors below the rank of petty officer at HMIS Talwar were refusing orders. The sailors rebelled, took control of the base, and forced the officers out. Throughout the day, sailors moved from ship to ship in Bombay Harbour, trying to convince others to join the uprising. Meanwhile, B. C. Dutt, who had been in solitary confinement, was allowed back at the Talwar barracks before his expected dismissal. He later became known as one of the main people who started the uprising. Within a day, the uprising had spread to 22 ships in the harbour and 12 other naval bases in Bombay. On the same day, RIN wireless stations, even as far away as Aden and Bahrain, joined the uprising. The sailors at HMIS Talwar had used the wireless devices at the signals school to talk directly with them.

Taking Over Bombay Harbour

On February 19, Admiral John Henry Godfrey, the commanding officer of the Royal Indian Navy, announced on All India Radio that he would use the strongest measures to stop the uprising, even if it meant destroying the Navy. Rear Admiral Arthur Rullion Rattray, second-in-command, inspected Bombay Harbour and saw that the unrest was widespread and out of control. Rattray wanted to talk with the sailors, but Auchinleck and Godfrey were against it. The events at HMIS Talwar had inspired sailors across Bombay and the Royal Indian Navy to join. They hoped for a revolution to overthrow British rule and supported their fellow sailors' complaints.

Throughout the day, many sailors went into the city with hockey sticks and fire axes. They caused traffic problems and sometimes took over vehicles. Motor launches seized at the harbour were paraded around, and crowds cheered them on at the piers. Protests and unrest broke out in the city. Gasoline was taken from trucks, tram tracks were set on fire, and the US Information Office was raided. The American flag inside was pulled down and burned in the streets.

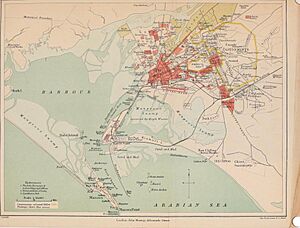

By the morning of February 20, 1946, it was reported that Bombay Harbour, including all its ships and naval bases, had been taken over by the sailors. This included 45 warships, 10-12 shore bases, 11 support vessels, and four groups of ships. About 10,000 sailors were involved. The harbour facilities included the Fort and Castle Barracks, the Central Communications Office (which handled all naval signals in Bombay), the Colaba receiving station, and the Royal Indian Navy hospital nearby. The warships included two destroyers, two older warships, one frigate, and four corvettes, among others.

The only ship in Bombay Harbour that did not join the uprising was the frigate HMIS Shamsher, which had Indian officers. The commanding officer of HMIS Shamsher, Lieutenant Krishnan, created a distraction and moved out of the harbour on February 18. Despite protests from his junior officer, Krishnan did not join the rebellion. He also managed to stop a protest from the sailors under his command with a "charismatic speech" where he used his Indian identity to keep control.

The rebellion also included naval bases near Bombay. HMIS Machlimar at Versova, an anti-submarine training school, was taken over by 300 sailors. HMIS Hamla at Marvé, which housed the landing craft wing of the RIN, was seized by 600 sailors. HMIS Kakauri, the center for sending sailors home, was taken by over 1,400 sailors living there. On Trombay Island, the Mahul wireless communications station and HMIS Cheetah, another demobilisation center, were also seized. HMIS Akbar at Kolshet, a training facility for special services sailors, was taken by 500 sailors. Two inland bases, HMIS Shivaji in Lonavala (a mechanical training base) and HMIS Feroze in the Malabar Hills (an officer's training facility), were also seized.

Strike Committee and Demands

On the afternoon of February 19, the sailors in Bombay Harbour gathered at HMIS Talwar. They elected the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC) to represent them and wrote down their "Charter of Demands." Warships and shore bases became voting areas for electing committee members. Most committee members are unknown, and many were reportedly under 25 years old. Among the known members were petty officer Madan Singh and signalman M. S. Khan, who were allowed to have informal talks. The "Charter of Demands" was sent to the authorities. It included both political and service-related requests.

On the warships and at the naval bases, the British flags were pulled down. Instead, the flags of the Indian National Congress, the All-India Muslim League, and the Communist Party of India were raised. The Communist Party of India's Bombay committee called for a general strike, which was supported by leaders from the Congress Socialist Party. However, the main leaders of the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League were against the uprising from the start. Disappointed by this opposition, the sailors pulled down the Congress and Muslim League flags, keeping only the red flags flying.

British Army Steps In

On February 20, 1946, the Naval Central Strike Committee told some sailors to go into the city to get public support. RIN trucks full of sailors entered European business areas of Bombay, shouting slogans to excite Indians. This led to fights between the sailors and Europeans, including servicemen. Police, students, and worker groups in the city went on sympathetic strikes to support the sailors. The Royal Indian Air Force units in Bombay also saw unrest. Their personnel, including pilots, refused to transport British troops into the city or fly bombers over the harbour. About 1,200 air force strikers marched in the city alongside the sailors. Striking civilian staff from Naval Accounts also joined the march.

Meanwhile, the British leaders decided to stand firm and only accept unconditional surrender. They refused any talks. Rear Admiral Rattray ordered all sailors to return to their barracks by 3:30 PM. General Rob Lockhart, the commanding officer of the Southern Command, was put in charge of stopping the uprising. The Royal Marines and the 5th Mahratta Light Infantry were sent to Bombay to push the protesting sailors back into their barracks.

The strike committee had advised the sailors not to fight with the army in the city. The sailors, hesitant to fight the police and army, retreated to the harbour by afternoon. However, the troops were not enough to push the sailors back into their barracks. Warning shots from machine guns and rifles were fired near the harbour to stop the army from moving forward. The sailors had taken positions at the harbour and were well-armed with small weapons and ammunition from the warships and naval bases. The warships in the harbour had powerful guns, which they aimed at the advancing troops and towards the land. HMIS Narbada and HMIS Jumna pointed their guns at the oil storage and other military buildings on the Bombay shoreline.

In the evening, Admiral John Henry Godfrey arrived in Bombay from New Delhi. The army had surrounded the harbour and naval areas. The sailors told The Free Press Journal that the government was trying to block them and cut off their food supply. At the same time, Godfrey offered to meet one of their demands: improving food quality. This reportedly confused the sailors. Parel Mahila Sangh, a communist-linked union, organized food relief from fishermen and mill workers in Bombay to be sent into the harbour.

On February 21, 1946, Admiral John Henry Godfrey made a statement on All India Radio, threatening the sailors to surrender immediately or face complete destruction. He had talked with the head of the British Navy, Sir Andrew Cunningham, who advised quickly stopping the uprising to prevent it from becoming a bigger conflict. A British naval fleet, including a cruiser, three frigates, and five destroyers, was called in from Singapore. Bombers from the Royal Air Force flew over the harbour to show British strength.

The Royal Marines were ordered to retake the Castle Barracks. The sailors fought with some army positions on land. The sailors tried to move into the city, but the army successfully pushed them back, stopping them from entering Bombay. Godfrey sent a message to the British Navy leaders asking for urgent help, saying the sailors could take the city. Meanwhile, sailors on ships in the harbour exchanged rifle fire with advancing British troops. The main guns of the RIN warships fired at the British troops approaching the barracks.

Around 4:00 PM, the firing from the warships stopped after instructions from the Strike Committee, and the sailors retreated from the barracks. The marines stormed the barracks in the evening, seized the ammunition storage, and secured all entrances and exits. With the marines now inside the harbour, the Central Strike Committee moved from the shore base HMIS Talwar to the advanced warship HMIS Narbada.

At the same time, Royal Indian Air Force personnel from the Andheri and Colaba camps rebelled and joined the sailors. Carrying white flags stained with blood, about 1,000 airmen occupied the Marine Drive of Bombay. They issued their own demands, similar to the "Charter of Demands," including a request for their pay to be the same as the Royal Air Force (RAF). Royal Indian Air Force personnel in the Sion area also went on strike to support the sailors.

Unrest in Bombay City

On February 22, 1946, British reinforcements arrived in Bombay from Poona. These included battalions from the Essex Regiment, the Queen's Regiment, and the Border Regiment, along with the 146th Regiment of the Royal Armoured Corps. An anti-tank battery also arrived. A curfew was put in place in the city. Fearing a wider, communist-inspired rebellion, the government decided to crack down on the protesters. During the unrest, up to 236 people were killed and thousands were injured. On February 23, 1946, the Naval Central Strike Committee asked all warships to fly black flags of surrender.

HMIS Hindustan and Karachi

News of the uprising at HMIS Talwar reached Karachi on February 19, 1946. That afternoon, sailors from the naval bases HMIS Bahadur, HMIS Himalaya, and HMIS Monze held a meeting at Manora Island beach. They decided to start a protest on February 21 with a march beginning at the Keamari jetty and moving through the city. They wanted to protest British rule and show unity between the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League.

However, on February 20, before the planned march, a dozen sailors from the old cruiser HMIS Hindustan left the ship. They refused to return unless certain officers were transferred, protesting against unfair treatment. Throughout the day, more sailors from HMIS Himalaya and other bases joined them. The group moved into the Keamari area shouting slogans like "Inquilab Zindabad" (Long live the revolution) and "Hindustan Azad" (Freedom for Hindustan). They urged businesses to start a general strike and then began marching towards the railway station, saying they planned to march on Delhi. Meanwhile, a second meeting was called, and they quickly decided to cancel the planned protest and support the sailors' actions in the city. The sailors, working through their association, organized for posters to be put up and slogans painted on walls in naval areas and the city, such as "We shall live as a free nation" and "Tyrants your days are over."

Taking Over Manora Island

On the morning of February 21, 1946, Manora Island was full of unrest. The warship HMIS Hindustan, docked at Karachi Harbour, had been seized by sailors at midnight. The officers were controlled, and the warship was moved to Manora Island. Within hours, the training bases HMIS Bahadur, HMIS Chamak (radar school), and HMIS Himalaya (gunnery school) were seized by about 1,500 sailors, all located on the island. British officers at HMIS Bahadur shot and killed one sailor during the takeover. His blood-soaked shirt became a flag for the protesting sailors. The other military ship in the harbour, HMIS Travancore, was also seized.

Local residents joined the uprising at the naval bases on Manora. By morning, the sailors were crossing to Keamari on civilian and military motor launches from the HMIS Himalaya jetty. Some sailors were caught by British patrol boats that fired at them. The patrol boats retreated when HMIS Hindustan started firing its guns in their direction. Two sailors on the launches died, and several were wounded in this small fight.

Meanwhile, troops from the 44th Indian Airborne Division, the Black Watch, and a British artillery unit were sent to Karachi for help. Unconfirmed reports said that many Indian regiments refused to fire at the sailors. The army mainly used British troops during the uprising and the unrest in the city that followed.

The authorities in Karachi were in close contact with those in Bombay. They wanted to prevent a similar situation where sailors and civilians worked together, which had caused a critical situation in Bombay. Police and British troops with Thompson submachine guns set up roadblocks at the bridges connecting Keamari with the rest of the city. These roadblocks stopped the sailors from entering the city, and hundreds of sailors were stuck in the Keamari area all day. Local dockyard workers joined the sailors and held protests, shouting slogans for revolution.

In the evening, the sailors in Keamari arranged meeting points with the workers and boatmen, and returned to the island. The sailors held several meetings that night on the island to plan for the next day. Around 11:00 PM, HMIS Chamak (the radar school) received information from HMIS Himalaya (the gunnery school and jetty) that HMIS Hindustan had been given an ultimatum to surrender by 10:00 AM the next morning. HMIS Hindustan was the only warship in the area and controlled the entrance to Karachi Harbour. On the morning of February 22, 1946, Commodore Curtis, the British commanding officer at the harbour, held talks at 8:30 AM. He came aboard the ship to persuade the sailors to surrender, offering "safe passage" to those who would do so by 9:00 AM. The surrender time was set to match low tide, which put the warship at a disadvantage compared to troops on land.

The talks did not work, and the ultimatum was ignored. The sailors were seen preparing to use the ship's weapons. Because of this, British troops advanced through Keamari and tried to board HMIS Hindustan. They started with sniper fire from a distance, aimed at those on the ship's deck. The sailors fired back with the ship's Oerlikon 20 mm cannons and heavy machine guns. Two main guns on the ship were ready, but their view was blocked by the low tide. In return, the artillery unit fired at the ship with mortars and field guns, including 75-millimeter howitzers. The warship did not fire all its weapons to avoid hitting innocent civilians in the city, given its blocked view. One of the main gun turrets exploded due to the shelling, causing a fire on board the ship as it tried to leave the harbour. At 10:55 AM, the sailors on HMIS Hindustan surrendered, and the battle ended.

In the morning, the British army had warned that any civilian coming within a mile of HMIS Hindustan would be shot. This made it harder for sailors to cross from Manora to Keamari, as fewer boatmen were willing to help. The fight with HMIS Hindustan had ended by the time some sailors made it across. They were met by British troops who had advanced into and occupied Keamari. Meanwhile, British paratroopers captured the naval bases on the island. The Black Watch was also ordered to retake Manora Island. An intelligence report said they captured the gunnery school at 9:50 AM. The report also stated that at that time, 7 RIN sailors were wounded, and 15 paratroopers were wounded on the island. The remaining sailors were trapped at the jetty on Manora, unable to cross to Keamari and facing the Black Watch behind them. In the end, 8-14 sailors were killed, 33 were wounded (including British troops), and 200 sailors were arrested.

Unrest in Karachi City

Movement and communication between Keamari and Karachi were cut off by military and police roadblocks from February 21 onwards. Civilian boats at Keamari were taken by British authorities and brought into the city. The military searched vehicles entering the city from Keamari to stop sailors from getting into Karachi. Much of the population lived near the ports, and Keamari was especially crowded with working-class people. As a result, daily life was severely disrupted by the military presence and roadblocks. Exaggerated stories of events spread through the city, and the people, who already supported the sailors, became even more angry and worried about the military. These stories were mainly spread by the boatmen and fishermen whose boats were taken, as they could still communicate with those in Keamari.

On February 22, 1946, flashes and sounds of gunfire from the conflict could be seen and heard in Karachi. The port area was filled with military vehicles, some of which were vandalized by civilians. Indian military police were shouted at by crowds, while British troops, military trucks, and messengers were attacked with stones on several roads. The sailors surrendered, but civil unrest had begun to spread through the city. The protests, which started on their own in the previous days, became more organized with the involvement of students and local leaders. In the evening, the Communist Party of India held a public meeting at Karachi Idgah park, which had about 1,000 people and was led by Sobho Gianchandani. Authorities said "dangerous and provocative anti-British speeches" were made at this meeting. A common idea expressed was that the sailors had shown how weapons could really be used, while civilians felt helpless without weapons or contact with the sailors. The meeting ended with a decision to call for a city-wide hartal (general strike) the next day.

On February 23, 1946, Karachi had a complete shutdown. Warehouses and stores were closed, tram workers were on strike, and college and school students protested in the streets. To prevent the civil unrest seen in Bombay a day earlier, authorities arrested three important communist leaders in the city. The district magistrate also put a section 144 order in Karachi, which banned gatherings of more than three people. However, the police force was not effective in enforcing the order because of low morale, absences, and some police officers working with the civilian protesters. Throughout the day, the streets filled as more and more people joined large protests and gatherings.

Many large gatherings, meetings, and protests were held. The Communist Party of India led a march of 30,000 people through the city. The captured sailors on Manora Island also went on a hunger strike in front of British troops. Many striking sailors, some identified as leaders, were arrested and sent to the military prison camp at Malir in the Thar Desert. At noon, thousands of people had gathered at Idgah park, joined by the Communist Party's march. The police were eventually sent to the park but were pushed back after several attempts to break up the crowd. Idgah became a center of resistance for the protesters. Later that day, some communist leaders asked the protesters to leave, but they could not control most of the crowd, who were energized by the previous day's radical messages and attacked nearby police.

The government called for the armed forces to be sent into the city. The crowd at the park, facing the arrival of British troops, scattered into smaller groups. The troops occupied the park in the afternoon. But the smaller groups, angered by the military presence, targeted government buildings like post offices, police stations, and the only European-owned Grindlays Bank in the city. Government buildings were vandalized, and a sub-post office was burned down. One group tried to capture the municipal building but was stopped by police, who arrested 11 young people, including a Communist Party leader. The crowds targeted Anglo-Indians, Europeans, and sometimes Indian government workers. They were stripped of their hats and ties, which were then burned. After this, British troops moved through the streets and sometimes shot to disperse the crowds. The crowds, mostly students and working-class people, left at night and returned home.

On February 24, 1946, the military forces in the city successfully enforced a curfew. The unrest calmed down over the next few days, and the military presence was removed by the end of February 26. Official figures for casualties from the shootings were 4-8 killed, 33 injured from police firing in self-defense, and 53 policemen injured.

Other Protests and Events

On February 20, 1946, it was reported that with the help of radio and telegraph messages from Bombay, the uprising had spread to all RIN sub-stations in India. These were located in Madras, Cochin, Vizagapatam, Jamnagar, Calcutta, and Delhi. The Bombay telegraphs also asked for help from the Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF) and Royal Indian Army Service Corps (RIASC). During the uprising, supplies meant for the RIASC were stolen by servicemen and sold to the sailors on the black market. HMIS India, the naval headquarters in New Delhi, saw about 80 signals operators refuse orders and barricade themselves inside their station.

On February 22, 1946, large protests by civilians began in several cities other than Bombay and Karachi, such as Madras, Calcutta, and New Delhi. Looting was widespread and targeted government buildings. Poor people looted grain stores, as well as jewelry shops and banks. Criminal groups were also reportedly involved.

Andaman Sea

The minesweeper fleet of the Royal Indian Navy, led by its command ship HMIS Kistna, was in the Andaman Sea. The fleet included six other ships. HMIS Kistna received news of the Bombay uprising during breakfast on February 20, 1946. The fleet's commanding officer spoke to the personnel, expressing sympathy for "fair goals" but stressing the importance of order and discipline. The next day, more news broadcasts increased tensions between officers and sailors, and rumors spread among the sailors. Without direct communication with the protesting sailors or access to print news, the sailors mainly learned about the uprising from their officers and could not fully understand the situation in Bombay.

On February 23, 1946, all seven ships of the minesweeper fleet stopped their duties and went on strike.

Madras

On February 19, 1946, about 150 sailors protested at the naval base HMIS Adyar in Madras. The sailors marched through the city streets, shouting slogans and attacking British officers who tried to stop them.

1,600 personnel from the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers at Avadi announced their decision to refuse orders and start a general strike.

On February 25, 1946, the city of Madras had a complete shutdown due to a general strike.

Calcutta

On February 22, 1946, the sailors of the frigate HMIS Hooghly (K330) began refusing orders. They were protesting the violent stopping of the uprising in Bombay and Karachi. The Communist Party of India called for a general strike in the city. About 100,000 workers took part in large protests and demonstrations over the next few days.

On February 25, 1946, British troops surrounded the frigate in Kolkata Harbour and imprisoned the disobedient sailors. The general strike in the city ended the next day.

Vizagapatnam

On February 22, 1946, British troops arrested 306 protesting sailors without using force.

Why There Was Not Much Support

The protesting sailors in the armed forces did not get much support from national political leaders. The sailors themselves also largely lacked a central leader.

Mahatma Gandhi spoke against the riots and the sailors' revolt. On March 3, 1946, he criticized the strikers for rebelling without being called to do so by a "prepared revolutionary party" and without the "guidance" of "political leaders of their choice." He also criticized the local Congress leader Aruna Asaf Ali, who was one of the few prominent political leaders to support the sailors. Gandhi said she would rather unite Hindus and Muslims in protest than through political talks. Gandhi's criticism also showed his awareness of the coming Partition of India. He stated, "If the union at the barricade is honest then there must be union also at the constitutional front."

The Muslim League also criticized the uprising. They argued that protesting in the streets was not the best way for sailors to express their complaints, no matter how serious they were. They believed that any movement needed to be led by recognized political leaders. They saw the spontaneous protests by the RIN strikers as something that could cause chaos and, at worst, destroy political agreement. This might have been what Gandhi and the Congress learned from the Quit India Movement in 1942. During that time, central control quickly broke down under British suppression, and local actions continued for a long time. It's possible they worried that the quick rise of strong public protests supporting the sailors would weaken central political authority when power was transferred. The Muslim League had seen quiet support for the "Quit India" campaign among its followers, even though the League itself was against it at the time. It is possible the League also realized the chance of unstable authority once power was transferred. This is certainly reflected in the opinion of the sailors who took part in the strike. Historians have concluded that the main political parties were uncomfortable because the public protests showed their weakening control over the people. This happened at a time when they could not agree with the British Indian government.

The Communist Party of India, the third largest political force at the time, fully supported the sailors. They organized workers to help, hoping to end British rule through revolution instead of talks. The two main parties, the Congress and the Muslim League, refused to support the sailors. The large scale of the uprising scared them, and they urged the sailors to surrender. Patel and Jinnah, who represented the different religious groups, agreed on this issue. Gandhi also criticized the 'Mutineers'. The Communist Party called for a general strike on February 22. There was a huge response, and over a hundred thousand students and workers came out onto the streets of Calcutta, Karachi, and Madras. The workers and students carried red flags and marched with slogans like "Accept the demands of the ratings" and "End British and Police cruelty." After surrendering, the sailors faced military trials, imprisonment, and unfair treatment. Even after 1947, the governments of independent India and Pakistan refused to let them rejoin the navy or offer them money. The only important Congress leader who supported them was Aruna Asaf Ali. Disappointed with the Congress Party's progress on many issues, Aruna Asaf Ali joined the Communist Party of India (CPI) in the early 1950s.

It has been thought that the Communist Party's support for the sailors was partly because they were trying to gain more power against the Indian National Congress.

The only major political groups that still talk about the revolt are the Communist Party of India and the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The Communist Party's writings describe the RIN Revolt as a spontaneous nationalist uprising that could have prevented the partition of India. They say it was betrayed by the leaders of the nationalist movement.

More recently, the RIN Revolt has been renamed the Naval Uprising. The sailors are now honored for their part in India's independence. Besides the statue in Mumbai, two important sailors, Madan Singh and B.C. Dutt, have had ships named after them by the Indian Navy.

What Happened After

Between February 25 and 26, 1946, the remaining sailors surrendered. They were promised by the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League that none of them would be punished. However, many sailors were arrested and imprisoned in difficult conditions in the following months. This happened despite resistance from national leaders and the surrender agreement that was supposed to protect them.

Steps were taken to prevent another rebellion. Firing parts were removed from warships, small weapons were locked away by British officers, and army troops were placed as guards on warships and at naval bases. Even after the uprising, British admirals did not want to give up control. They still believed the navy would serve British interests in the Indian Ocean.

Among the British, confidence in the Royal Indian Navy's loyalty was shattered. The uprising damaged the reputation of John Henry Godfrey. He was blamed for not preventing and controlling the rebellion, which had put British security in the Indian Ocean at risk. Although he was not officially punished by the navy and continued to serve, he was informally criticized, for example, by not receiving honors.

Investigations

Many groups were set up at naval bases across India by naval authorities to investigate why and how the uprising happened. These groups were made up of British armed forces officers. They mainly took statements from RIN officers and a small number of other ranks. The uprising was found to be caused by problems like not enough information, a lack of regular inspections, and a shortage of experienced petty officers, chiefs, and officers.

On March 8, 1946, Commander-in-Chief Claude Auchinleck suggested a special investigation to find out the causes and origin of the uprising. The members of this investigation were:

- The Hon'ble Sir Saiyid Fazl Ali, Chief Justice of Patna High Court (Chairman)

- Mr. Justice K. S. Krishnaswami Iyengar, Chief Justice, Cochin State

- Mr. Justice Mahajan, Judge, Lahore High Court

- Vice-Admiral W. R. Patterson, a high-ranking officer in the British Navy

- Major-General T. W. Rees, a high-ranking officer in the British Indian Army

The investigation became very political. It was criticized for being too focused on legal rules, unfair in its methods, and against the military. Its report was released publicly in January 1947. British naval officers remained doubtful of its findings.

Impact of the Uprising

Clement Attlee announced the Cabinet Mission to India after the uprising. This mission was sent to discuss India's independence.

Indian historians see the uprising as a revolt for independence against British rule. British scholars note that there was no similar unrest in the Army. They have concluded that the problems within the Navy itself were key to the uprising. There was poor leadership and a failure to make the sailors believe in the importance of their service. Also, there was tension between officers (mostly British), petty officers (mostly Punjabi Muslims), and junior sailors (mostly Hindu). There was also anger about how slowly sailors were being sent home after the war.

The main complaints were about how slowly sailors were being released from wartime service. British units were close to rebelling, and it was feared that Indian units might follow. An intelligence summary on March 25, 1946, admitted that Indian Army, Navy, and Air Force units could no longer be trusted. For the Army, it said, "only day to day estimates of steadiness could be made." This situation has been called the "Point of No Return."

The British authorities in 1948 called the 1946 Indian Naval Mutiny a "larger communist conspiracy" against the British Crown, stretching from the Middle East to the Far East.

However, an important question remains: what would have happened to India's internal politics if the revolt had continued? Indian nationalist leaders, especially Gandhi and the Congress leadership, seemed worried that the revolt would harm their plan for a peaceful and constitutional agreement. They wanted to negotiate with the British, not within the two main groups representing Indian nationalism—the Congress and the Muslim League.

In 1967, during a discussion marking 20 years of India's independence, the British High Commissioner at the time, John Freeman, revealed that the 1946 uprising had raised fears of another large-scale rebellion like the Indian Rebellion of 1857. This was a concern because 2.5 million Indian soldiers had fought in World War II.

Legacy

In India, the naval uprising is recognized as a major event in the Indian independence movement.

The uprising was supported by Marxist artists and cultural activists from Bengal. Salil Chaudhury wrote a revolutionary song about it in 1946. Later, Hemanga Biswas wrote a tribute. A Bengali play based on the incident, Kallol (Sound of the Wave), by playwright Utpal Dutt, became an important anti-establishment statement. When it was first performed in 1965 in Calcutta, it drew large crowds. Soon after, the government banned it, and its writer was imprisoned for several months.

The revolt is part of the background for John Masters' book Bhowani Junction, which is set at this time. Several Indian and British characters in the book discuss the revolt and what it meant.

The 2014 Malayalam movie Iyobinte Pusthakam features the main character, Aloshy, as a Royal Indian Navy sailor who took part in the uprising.

|

See also

- Communist involvement in Indian Independence movement

- Communism in India

- Anushilan Samiti

- Ghadar Movement

- India House

- Tebhaga Movement

- Quit India Movement

- Indian National Army

- Indian Independence movement

- Indian Rebellion of 1857

- Royal Air Force mutiny

Naval mutinies:

- Revolt of the Lash

- Kiel mutiny

- Kronstadt rebellion

- Chilean naval mutiny of 1931

- Invergordon Mutiny

- 1936 Naval Revolt

- Cocos Islands mutiny

- 1944 Greek naval mutiny

- 1947 Royal New Zealand Navy mutinies

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |