Sidney Reilly facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sidney Reilly |

|

|---|---|

| "Ace of Spies"; Dr. T. W. Andrew; Mr. Constantine; George Bergmann | |

Reilly's 1918 German passport

(issued to "George Bergmann") |

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Operation(s) | Lockhart Plot D'Arcy Concession Zinoviev letter |

| Codename(s) | S.T.I. |

|

|

|

| Born | c. 1873 Possibly Odessa, Russian Empire |

| Died | 5 November 1925 (aged 51) Possibly Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1917–1921 |

| Rank | Second Lieutenant |

| Awards | Military Cross |

Sidney George Reilly (born around 1873 – died 5 November 1925), was known as the "Ace of Spies". He was a secret agent born in Russia who worked for the British Secret Service. People say he spied for at least four different powerful countries. Records show he was involved in spying in London in the 1890s, in Manchuria before the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), and in a failed attempt in 1918 to overthrow Vladimir Lenin's government in Moscow.

Reilly disappeared in Soviet Russia in the mid-1920s. He was tricked by a Soviet spy operation called Operation Trust. A British diplomat, R. H. Bruce Lockhart, wrote a book in 1932 called Memoirs of a British Agent. This book told about his and Reilly's efforts to overthrow the Soviet government. The book became very popular and made Reilly famous around the world.

Newspapers called Reilly "the greatest spy in history" and "the Scarlet Pimpernel of Red Russia". The London Evening Standard newspaper published a story about his adventures in 1931 called "Master Spy". Ian Fleming, the author of the James Bond novels, used Reilly as an idea for his famous character. Reilly is seen as a very important figure in the stories of modern British spying.

Contents

Early Life and Identity

The real details about Sidney Reilly's birth and early life are still a mystery. Reilly himself told many different stories about his past to confuse people. He claimed to be the son of an Irish sailor, an Irish priest, or a rich landowner.

According to Soviet secret police files from 1925, he might have been born Zigmund Markovich Rozenblum on March 24, 1874, in Odessa. This city was a port on the Black Sea in the Russian Empire. These files say his father, Markus, was a doctor and shipping agent, and his mother came from a poor noble family.

Other sources say he was born Georgy Rosenblum in Odessa on March 24, 1873. Another story says his birth name was Salomon Rosenblum in Kherson Gubernia. He was supposedly the son of Polina (or "Perla") and Dr. Mikhail Abramovich Rosenblum, who was a cousin of Reilly's father. Some also think he was the son of a merchant ship captain and Polina.

One more source states he was born Sigmund Georgievich Rosenblum on March 24, 1874. He was the only son of Pauline and Gregory Rosenblum, a wealthy Polish-Jewish family. They had an estate in Bielsk in the Grodno Province of Imperial Russia. His father was known as George, which is why Sigmund's middle name was Georgievich. His family seemed to have connections with Polish nationalist groups. This was because Pauline was close friends with Ignacy Jan Paderewski, who later became the Prime Minister of Poland.

Journeys Abroad

Reports from the Russian secret police, the Okhrana, say that Rosenblum was arrested in 1892. This was for his political activities and for carrying messages for a revolutionary group. He avoided serious punishment. Later, he became friends with Okhrana agents. This might mean he was a police informant even when he was young.

After Rosenblum was released, his father told him that his mother had died. He also said that his biological father was her Jewish doctor, Mikhail A. Rosenblum. Upset by this news, he pretended to die in Odessa harbor. He then secretly boarded a British ship going to South America. In Brazil, he used the name Pedro. He worked different jobs like a dock worker, a road builder, and a cook for a British intelligence group in 1895.

He supposedly saved the group and a Major Charles Fothergill when local people attacked them. Rosenblum took a British officer's pistol and killed the attackers. Fothergill rewarded him with money, a British passport, and a trip to Britain. There, Pedro became Sidney Rosenblum.

However, other records tell a different story about his time in Brazil. Evidence suggests Rosenblum arrived in London from France in December 1895. This was after he got a lot of money in a dishonest way and quickly left Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, a suburb of Paris. According to this story, Rosenblum and his Polish helper, Yan Voitek, robbed two Italian anarchists on December 25, 1895. They took a large amount of money meant for revolutionary activities. One anarchist died from knife wounds.

The French newspaper L'Union Républicaine de Saône-et-Loire reported the event. Police found that one of the attackers matched Rosenblum's description. But he was already on his way to Britain. His helper, Voitek, later told British intelligence about this event and other dealings with Rosenblum.

Before this, Rosenblum had met Ethel Lilian Boole. She was a young English writer involved with Russian groups living outside Russia. They became close, and he told her about his past. After their relationship ended, they kept writing to each other. In 1897, Boole published The Gadfly, a popular novel. Its main character was supposedly based on Reilly's life as Rosenblum.

For many years, some writers doubted the relationship between Reilly and Boole. But in 2016, new evidence was found in old letters. These letters confirmed that Reilly and Boole had a relationship around 1895 in Florence. Some wonder if he truly cared for Boole. He might have been a paid police informant, reporting on her and other radical friends.

Life in London: 1890s

In early 1896, Reilly continued to use the name Rosenblum. He lived in an apartment building in London. He started a company that sold special medicines. He also became a paid informant for William Melville. Melville was a superintendent of Scotland Yard's Special Branch, which dealt with political crimes. Melville later led a special section of the British Secret Service Bureau, which started in 1909.

In 1897, Rosenblum started a relationship with Margaret Thomas. She was the young wife of Reverend Hugh Thomas. Rosenblum met Rev. Thomas through his medicine company, as Thomas had a kidney problem and was interested in the "miracle cures" Rosenblum sold. Rev. Thomas introduced Rosenblum to his wife at his home. On March 4, 1898, Hugh Thomas changed his will, making Margaret a manager of his estate. He was found dead in his room on March 12, 1898, just a week after the new will was made.

A mysterious Dr. T. W. Andrew, who looked like Rosenblum, said Thomas died from the flu and that no investigation was needed. Records show there was no Dr. T. W. Andrew in Great Britain at that time. Margaret Thomas wanted her husband's body buried quickly. She inherited a large sum of money. The police did not investigate Dr. T. W. Andrew or the nurse Margaret hired, who had been linked to another suspicious death.

Four months later, on August 22, 1898, Rosenblum married Margaret Thomas in London. This marriage gave Rosenblum the wealth he wanted. It also gave him a reason to change his identity from Sigmund Rosenblum. With Melville's help, he created a new identity: "Sidney George Reilly." This new identity was important for his plan to return to the Russian Empire and travel to the Far East. Reilly got his new identity and nationality without official paperwork. This suggests that someone in power helped him. This help was likely to prepare him for his upcoming work for British intelligence in Russia.

Russia and the Far East

[Sidney Reilly's role] is one of the unsolved riddles about the Russo-Japanese War.

—Ian H. Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War

In June 1899, Reilly and his wife Margaret traveled to Emperor Nicholas II's Russian Empire. They used Reilly's British passport, which was likely fake and created by William Melville. In St. Petersburg, Japanese General Akashi Motojiro asked Reilly to work for the Japanese Secret Intelligence Services. Motojiro believed that spies who worked for money were more reliable. He thought Reilly was such a person.

Tensions between Russia and Japan were growing, leading to war. Motojiro had a large budget to get information on Russian troops and navy. Motojiro told Reilly to offer money to Russian revolutionaries. In return, Reilly was to get information about Russian intelligence and, more importantly, the strength of the Russian armed forces, especially in the Far East. Reilly agreed to work for Motojiro. This meant he was now a spy for both the British War Office and the Japanese Empire. While his wife Margaret stayed in St. Petersburg, Reilly explored the Caucasus region for its oil. He reported his findings to the British Government, which paid him for this job.

Just before the Russo-Japanese War, Reilly appeared in Port Arthur, Manchuria. He pretended to be a timber company owner. He stayed there for four years, learning about the politics of the Far East. He also gained some influence in the spying activities in the area. At this time, he was still a double agent, working for both the British and Japanese governments. Port Arthur, controlled by Russia, was under threat of a Japanese invasion. Reilly and his business partner, Moisei Akimovich Ginsburg, used this situation to their advantage. They bought and resold huge amounts of food, raw materials, medicine, and coal. They made a lot of money as people who profit from war.

Reilly had an even bigger success in January 1904. He and a Chinese engineer, Ho Liang Shung, supposedly stole the Port Arthur harbor defense plans for the Japanese Navy. Using these stolen plans, the Japanese Navy sailed at night through the Russian minefield protecting the harbor. They launched a surprise attack on Port Arthur on the night of February 8–9, 1904. However, the stolen plans did not help the Japanese much. Despite good conditions for a surprise attack, their results were not very good. Although many Russians died defending Port Arthur, Japanese losses were much higher. These losses almost ruined their war effort.

According to writer Winfried Lüdecke, Reilly quickly became a suspect to Russian authorities in Port Arthur. He then found out one of his business helpers was a Russian spy. So, he decided to leave the region. After leaving Port Arthur, Reilly traveled to Imperial Japan with an unknown woman. The Japanese government paid him well for his spying work. If he went to Japan, it was likely for payment. He could not have stayed long, because by February 1905, he was in Paris. By the time he returned to Europe from the Far East, Reilly had become a confident international adventurer. He spoke several languages, and his spying skills were wanted by many powerful countries. At the same time, he was described as someone who took unnecessary risks. This trait later earned him the nickname "reckless" from other British agents.

European Adventures

Oil Deal in Persia

While Reilly was briefly in Paris, he met William Melville again. Melville had left his job at Scotland Yard's Special Branch. He was now in charge of a new intelligence section in the War Office. Melville used his foreign contacts to run spy operations. Reilly's meeting with Melville was important. Within weeks, Melville used Reilly's skills in what became known as the D'Arcy Affair.

In 1904, the British Navy thought oil would replace coal as their main fuel. Since Britain did not have much oil, they needed to find and secure supplies overseas. The British Navy learned that an Australian mining engineer, William Knox D'Arcy, had a valuable agreement for oil rights in southern Persia. D'Arcy was also trying to get a similar agreement from the Ottoman Empire for oil rights in Mesopotamia. The British Navy wanted D'Arcy to sell his oil rights to the British Government, not to the French de Rothschilds.

The British Navy asked Reilly to find William D'Arcy in Cannes, France. Reilly approached him in disguise. Dressed as a Catholic priest, Reilly went to a private meeting on the Rothschild yacht. He pretended to collect donations for a charity. He then secretly told D'Arcy that the British could offer him a better deal. D'Arcy quickly stopped talking with the Rothschilds. He returned to London to meet with the British Navy.

However, some writers like Andrew Cook question if Reilly was really involved in this event. In February 1904, Reilly might still have been in Port Arthur. Cook thinks it was Reilly's boss, William Melville, and another British intelligence officer who did the job. Another idea, from the book The Prize, says the British Navy created a group of "patriots" to keep D'Arcy's oil rights for Britain. D'Arcy himself was happy to help.

Even though Reilly's exact role is unclear, it is confirmed that he stayed in the French Riviera after the event. This area is very close to where the Rothschild yacht was. After the D'Arcy Affair, Reilly traveled to Brussels. In January 1905, he returned to St. Petersburg, Russia.

First World War Activities

Some early stories about Reilly say he lived as a spy in Germany from 1917 to 1918. They claim he worked behind German lines and even attended a German War meeting with Kaiser Wilhelm II. However, most later biographies agree that Reilly was in the United States between 1915 and 1918. This means he could not have been in Germany.

Later writers believe Reilly was making money in the weapons business in New York City. At the same time, he secretly worked for British intelligence. He might have been involved in acts of "German sabotage." These acts were meant to make the United States join the war against Germany.

Historian Christopher Andrew notes that Reilly spent most of the first two and a half years of the war in the United States. Author Richard B. Spence also states that Reilly lived in New York City for at least a year, from 1914 to 1915. There, he arranged to sell weapons to both the German and Russian armies. However, when the United States entered the war in April 1917, Reilly's business became less profitable. His company was not allowed to sell weapons to the Germans anymore. After the Russian revolution in October 1917, the Russians also stopped buying weapons.

Facing money problems, Reilly wanted to restart his paid spy work for the British government in New York City. This is confirmed by papers from Norman Thwaites, the head of British intelligence (MI1(c)) in New York. These papers show that Reilly asked Thwaites for spying work in 1917–1918. Thwaites was interested in getting information about radical groups in the United States, especially any links between American socialists and Soviet Russia.

So, under Thwaites's guidance, Reilly likely worked with other British spies in New York City. Their main job was to work with the U.S. government on information about Germany and Soviet Russia. But the British agents also secretly tried to get trade secrets from American companies for their British rivals.

Thwaites was impressed with Reilly's work in New York. He wrote a letter of recommendation to Mansfield Cumming, the head of MI1(c). Thwaites also suggested Reilly go to Toronto to get a military rank. That is why Reilly joined the Royal Flying Corps Canada. On October 19, 1917, Reilly became a temporary second lieutenant. After this, Reilly traveled to London in 1918. There, Cumming officially made Lieutenant Reilly a staff officer in the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). He then sent Reilly to Russia to work against the Bolsheviks. According to Reilly's wife, Pepita Bobadilla, Reilly was sent to Russia to "stop the work being done there by German agents" who supported radical groups. He was also to "find out about the general feeling" in Russia.

Reilly arrived in Russia through Murmansk before April 5, 1918. He contacted Alexander Grammatikov, a former Okhrana agent. Grammatikov believed the Soviet government was controlled by criminals and people who had been released from mental hospitals. Grammatikov arranged for Reilly to meet with either General Mikhail Bonch-Bruyevich or Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich, a secretary for the Soviet government. With their secret help, Reilly pretended to support the Bolsheviks. Grammatikov also told his niece, Dagmara Karozus, a dancer, to let Reilly use her apartment as a safe place. Through Vladimir Orlov, a former Okhrana contact who was now a Cheka official, Reilly got travel permits as a Cheka agent.

The Ambassadors' Plot

In 1918, behind-the-scenes helpers such as ... Sidney Reilly, the erstwhile Russian double agent who was operating on Britain's behalf, were involved in the formulation and execution of various attempts to snatch both Russia and the [Romanov family] from the Bolsheviks.

The plan to remove the Bolshevik government and possibly harm Vladimir Lenin is considered Reilly's boldest adventure. This plot, later called the Lockhart-Reilly Plot, has caused much debate. Did the Allies try to overthrow the Bolsheviks in the summer of 1918? And did Felix Dzerzhinsky's Cheka (Soviet secret police) discover the plot at the last minute, or did they know about it all along? At the time, the American Consul-General DeWitt Clinton Poole publicly said the Cheka planned the whole thing and that Reilly was a Bolshevik agent trying to trick people. Later, Robert Bruce Lockhart said he was "not to this day sure of the extent of Reilly's responsibility."

In January 1918, the young Lockhart, a junior British diplomat, was chosen by Prime Minister David Lloyd George for a secret mission to Soviet Russia. Lockhart's goals were to talk with Soviet leaders, weaken Soviet-German relations, encourage Soviets to fight Germany, and push them to restart the war on the Eastern Front. By April, Lockhart had failed. He started asking for a full Allied military attack on Russia. At the same time, Lockhart told Reilly to find anti-Bolshevik groups to start an uprising in Moscow.

In May 1918, Lockhart, Reilly, and other Allied agents met many times with Boris Savinkov. Savinkov led a group against the revolution. He had been a minister in the previous Russian government and was a key opponent of the Bolsheviks. Savinkov's group had thousands of fighters, and he was open to Allied ideas to remove the Soviet government. Lockhart, Reilly, and others then contacted anti-Bolshevik groups connected to Savinkov. Lockhart and Reilly supported these groups with money from the British Secret Intelligence Service. They also worked with American and French officials in Moscow.

Planning the Uprising

In June, some soldiers from Colonel Eduard Berzin's Latvian Riflemen started appearing in anti-Bolshevik groups. They were directed to a British naval officer, Francis Cromie, and his assistant, Mr. Constantine, who was actually Reilly. Unlike his past spy missions, Reilly worked closely with Cromie in Petrograd. They tried to recruit Berzin's Latvians and arm anti-Bolshevik forces. At the time, Cromie supposedly worked for British Naval Intelligence and led its operations in northern Russia.

Berzin's Latvians were considered the special guards of the Bolsheviks. They were trusted with the safety of both Lenin and the Kremlin. The Allied plotters believed their help was very important for the planned uprising. With the help of the Latvian Riflemen, the Allied agents hoped to "capture both Lenin and Trotsky at a meeting in the first week of September."

Reilly arranged a meeting between Lockhart and the Latvians at the British office in Moscow. He supposedly spent "over a million rubles" to bribe the Red Army troops guarding the Kremlin. At this point, Cromie, Reilly, Lockhart, and other Allied agents planned a full uprising against the Bolshevik government. They made a list of Soviet military leaders who would take over after the government fell. Their goal was to capture or kill Lenin and Trotsky, set up a temporary government, and end Bolshevism. They believed that Lenin and Trotsky "were Bolshevism," and without them, the Soviet movement would fall apart.

Since Lockhart's diplomatic role prevented him from openly spying, he chose to oversee the activities from a distance. He gave Reilly the job of leading the uprising. To help with this, Reilly supposedly got a job in the criminal branch of the Petrograd Cheka. During this time of plots, Reilly and Lockhart became better acquainted. Lockhart later described Reilly as "a man of great energy and personal charm, very attractive to women and very ambitious." He also said Reilly's "courage and indifference to danger were superb." Lockhart never openly questioned Reilly's loyalty to the Allies. But he privately wondered if Reilly had made a secret deal with Colonel Berzin and his Latvian Riflemen to take power for themselves later.

Lockhart thought Reilly was a very ambitious man. He believed that if their uprising had succeeded, Reilly might have tried to become the head of the new government using Berzin's Latvian Riflemen. However, the Allied plotters did not know that Berzin was a loyal commander who supported the Soviet government. Although he was not a Cheka agent, he told Dzerzhinsky's Cheka that Reilly had approached him. He said Allied agents had tried to get him to join a possible uprising. This information did not surprise Dzerzhinsky. The Cheka had already gotten access to British diplomatic codes in May. They were closely watching the anti-Bolshevik activities. Dzerzhinsky told Berzin and other Latvian officers to pretend to agree with the Allied plotters. He told them to report every detail of their planned operation.

The Plot Fails

While Allied agents worked against the Soviet government, rumors spread about an upcoming Allied military attack in Russia. This attack was supposed to overthrow the new Soviet government. It would replace it with a new government willing to rejoin the war against Germany. On August 4, 1918, an Allied force landed in Arkhangelsk, Russia. This started a military operation called Operation Archangel. Its stated goal was to stop Germany from getting Allied military supplies stored in the region. In response, the Bolsheviks raided the British diplomatic mission on August 5. This disrupted a meeting Reilly had set up between the anti-Bolshevik Latvians, other officials, and Lockhart.

Reilly was not bothered by these raids. On August 17, 1918, he held meetings between Latvian military leaders. He also worked with Captain George Alexander Hill, a British agent who spoke many languages and worked in Russia.

Hill later described Reilly as "a dark, well-groomed, very foreign-looking man." He said Reilly had "an amazing understanding of the situation" and was "a man of action." They agreed the uprising would happen in the first week of September. It would take place during a meeting of the Soviet government at the Bolshoi Theatre. On August 25, another meeting of Allied plotters supposedly happened at the American Consulate in Moscow. By this time, the Allied plotters had many agents and saboteurs across Soviet Russia. Their main goal was to disrupt the country's food supplies. They believed that combined with the planned military uprising in Moscow, a severe food shortage would cause public unrest. This would further weaken the Soviet authorities. In turn, the Soviets would be overthrown by a new government friendly to the Allied Powers. This new government would then restart fighting against Kaiser Wilhelm II's Germany.

On August 28, Reilly told Hill that he was immediately leaving Moscow for Petrograd. There, he would discuss the final details of the uprising with Commander Francis Cromie at the British consulate. That night, Reilly traveled easily between Moscow and Petrograd. This was because he had identification as a member of the Petrograd Cheka and Cheka travel permits.

On August 30, Boris Savinkov ordered a military student named Leonid Kannegisser to shoot and kill Moisei Uritsky. Uritsky was the head of the Petrograd Cheka. He was the second most powerful man in the city after Grigory Zinoviev. His murder was seen as a big blow to the Cheka and the Bolshevik leaders. After killing Uritsky, a panicked Kannegisser sought safety at the British mission where Cromie lived. Savinkov and other plotters might have been hiding there temporarily. Kannegisser was forced to leave the building. He put on a long coat and fled into the city streets. He was caught by Red Guards after a violent fight.

On the same day, Fanya Kaplan, a former anarchist, shot and wounded Lenin. This happened as he left a factory in Moscow. As Lenin exited the building, Kaplan called out to him. When Lenin turned, she fired three shots. One bullet just missed Lenin's heart and went into his lung. Another bullet lodged in his neck. Because of these serious wounds, Lenin was not expected to live. The attack was widely reported in Russian newspapers. It created much sympathy for Lenin and made him more popular. However, because of this assassination attempt, the meeting between Lenin and Trotsky was postponed. This was the meeting where the bribed soldiers were supposed to capture them for the Allies. At this point, Reilly was told by his fellow plotter, Alexander Grammatikov, that "the [Socialist Revolutionary Party] fools have struck too early."

Cheka's Response

It is not known if Kaplan was part of the Ambassadors' Plot or truly responsible for the attack on Lenin. However, the murder of Uritsky and the failed attack on Lenin were used by Dzerzhinsky's Cheka. They used these events to blame anyone who was unhappy or foreign in a big conspiracy. This led to a large-scale response called the "Red Terror". Thousands of political opponents were arrested. Many people were executed across the city. The Cheka's strong response likely ruined most of the plans by Cromie, Lockhart, Reilly, and other plotters.

Using lists from secret agents, the Cheka began to clear out the "nests of conspirators" in foreign embassies. In doing so, they arrested key people important to the planned uprising. On August 31, 1918, the Cheka believed Savinkov and other plotters were hiding in the British consulate. A Cheka group raided the British consulate in Petrograd and killed Cromie, who fought back. Before his death, Cromie might have been trying to tell other plotters to speed up their planned uprising. Before the Cheka group stormed the consulate, Cromie burned important papers about the plot.

Newspapers reported that he bravely fought on the first floor of the consulate with only a revolver. In close combat, he killed three Cheka soldiers before he was killed. Witnesses said Cromie was shot by the Cheka while going down the consulate's main staircase. The Cheka group searched the building. They used their rifle butts to keep diplomatic staff away from Cromie's body. The Cheka then arrested over forty people who had sought safety inside the British consulate. They also seized hidden weapons and documents. They claimed these documents showed the consulate staff were involved in the upcoming uprising. Cromie's death was publicly described as self-defense by the Bolshevik agents, who said they were forced to shoot back.

Meanwhile, Lockhart was arrested by Dzerzhinsky's Cheka. He was taken to Lubyanka Prison. During a tense interview with a Cheka officer holding a pistol, he was asked, "Do you know the Kaplan woman?" and "Where is Reilly?" When asked about the uprising, Lockhart and other British people said it was nonsense. Afterward, Lockhart was put in the same cell as Fanya Kaplan. The Cheka guards hoped she might show some sign of knowing Lockhart or other British agents. However, Kaplan showed no sign of recognizing Lockhart or anyone else. When it became clear that Kaplan would not name any helpers, she was executed in the Kremlin's Alexander Garden on September 3, 1918. Lockhart was later released and sent out of the country. This was in exchange for Maxim Litvinov, a Soviet official in London who had been arrested by the British government. Unlike Lockhart's good luck, many others involved in the planned uprising faced "imprisonment, harsh questioning to force confessions, and death." Yelizaveta Otten, Reilly's main messenger, was arrested. His other mistress, Olga Starzheskaya, was also arrested. After questioning, Starzheskaya was imprisoned for five years. Another messenger, Mariya Fride, was also arrested at Otten's apartment with a message she was carrying for Reilly.

Escape from Russia

On September 3, 1918, the Pravda and Izvestiya newspapers made the failed uprising a big story on their front pages. Headlines angrily called the Allied representatives and other foreigners in Moscow "Anglo-French Bandits." The papers gave Reilly credit for the uprising. When he was identified as a key suspect, a widespread search began. Reilly "was hunted through days and nights as he had never been hunted before." His photograph with a full description and a reward was posted everywhere. The Cheka raided his supposed hiding place, but Reilly escaped capture. He met Captain Hill while in hiding. Hill later wrote that Reilly, despite narrowly escaping his pursuers, "was absolutely cool, calm and collected." He was "not in the least downhearted" and only wanted to "gather together the broken threads and starting afresh."

Hill suggested that Reilly escape from Russia through Ukraine to Baku. They would use their network of British agents for safe houses and help. However, Reilly chose a shorter, more dangerous route north. This route went through Petrograd and the Baltic Provinces to Finland. He wanted to get their reports to London as early as possible. With the Cheka closing in, Reilly, carrying a Baltic German passport given by Hill, pretended to be a secretary from an embassy. He left the region in a train car reserved for the German Embassy. In Kronstadt, Reilly sailed by ship to Helsinki. He reached Stockholm with the help of local smugglers. He arrived safely in London on November 8.

While safe in England, Reilly, Lockhart, and other agents were tried in absentia (meaning they were not present) before the Supreme Revolutionary Tribunal. This trial began on November 25, 1918. About twenty people faced charges in the trial. Most of them had worked for the Americans or the British in Moscow. The case was led by Nikolai Krylenko. He believed that political reasons, not criminal guilt, should decide a case's outcome.

Krylenko's case ended on December 3, 1918. Two people were sentenced to be shot. Others were sentenced to prison or forced labor for up to five years. So, the day before Reilly met Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming ("C") in London for a report, the Russian Izvestia newspaper reported that both Reilly and Lockhart had been sentenced to death in absentia. This was for their roles in the attempted uprising against the Bolshevik government. The sentence was to be carried out immediately if either of them were caught in Soviet territory. This sentence would later be carried out on Reilly when he was caught by Dzerzhinsky's OGPU in 1925.

Activities from 1919 to 1924

Russian Civil War

Within a week of their return and debriefing, the British Secret Intelligence Service and the Foreign Office sent Reilly and Hill back to South Russia. They went under the cover of being British trade delegates. Their job was to find information about the Black Sea coast. This information was needed for the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. At that time, the region had many groups against the Bolsheviks. They traveled pretending to be British merchants. They had official papers from the Department of Overseas Trade. Over the next six weeks, Reilly wrote twelve reports. These reports covered different aspects of the situation in South Russia. Hill personally delivered them to the Foreign Office in London.

Reilly identified four main factors in South Russia at this time: the Volunteer Army, the local governments in Kuban, Don, and Crimea, the Petlyura movement in Ukraine, and the economic situation. He believed that what happened next in this region would depend on how these factors interacted. But most importantly, it would depend on how the Allies acted towards them. Reilly suggested that the Allies help organize South Russia. This would make it a good base for a strong attack against the Petlyura movement and Bolshevism. He thought that "The military Allied assistance required for this would be comparatively small."

Reilly's mention of Odessa referred to the successful landing there on December 18, 1918. French troops, helped by a small group of Volunteers, took control of the city from the Petlyurists.

Reilly believed that Allied military help for the Volunteer Army was urgent. But he thought economic help for South Russia was "even more pressing." Manufactured goods were so scarce in this region that even a small contribution from the Allies would have a very good effect. Reilly also supported their request for the Allies to print "500 Million roubles of Nicholas money." He said that even though this was not a long-term solution, it was the only immediate fix. Lack of money was one reason Reilly gave for the White forces' lack of activity in spreading their message. They also lacked paper and printing presses for propaganda. Reilly claimed that the White forces now fully understood the benefits of propaganda.

Final Marriage

While visiting Berlin after the war in December 1922, Reilly met a young actress named Pepita Bobadilla. This happened at the Hotel Adlon. Bobadilla was a charming blonde who falsely claimed to be from South America. Her real name was Nelly Burton. She was the widow of Charles Haddon Chambers, a well-known British playwright. For several years, Bobadilla had become known both as Chambers' wife and for her stage career as a dancer. On May 18, 1923, after a quick romance, Bobadilla married Reilly at a civil office in London. Captain Hill was a witness. Since Reilly was already married at the time, this marriage was not legal.

Bobadilla later described Reilly as a serious person. She found it strange that he never had guests at their home. Except for two or three acquaintances, hardly anyone could say they were his friend. Still, their marriage was reportedly happy. Bobadilla believed Reilly was "romantic," "a good companion," "a man of infinite courage," and "the ideal husband." Their marriage lasted only 30 months before Reilly disappeared in Russia and was executed by the Soviet OGPU.

Career with British Intelligence

[Mansfield] Cumming's most remarkable, though not his most reliable, agent was Sidney Reilly, the dominating figure in the mythology of modern British espionage. Reilly, it has been claimed, 'wielded more power, authority and influence than any other spy,' was an expert assassin, and possessed eleven passports and a wife to go with each.

Throughout his life, Reilly had a close but sometimes difficult relationship with British intelligence. In 1896, William Melville recruited him for the spy network of Scotland Yard's Special Branch. Through his close connection with Melville, Reilly worked as a secret agent for the Secret Service Bureau. This bureau was created by the Foreign Office in October 1909. In 1918, Reilly started working for MI1(c), an early name for the British Secret Intelligence Service, under Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming. He was supposedly trained by this organization and sent to Moscow in March 1918. His mission was to remove Vladimir Ilyich Lenin or try to overthrow the Bolsheviks. He had to escape after the Cheka uncovered the so-called Lockhart Plot against the Bolshevik government. Later stories about his life include many tales about his spying deeds. It has been claimed that:

- In the Second Boer War, he pretended to be a Russian weapons merchant to spy on Dutch weapon shipments.

- He got information about Russian military defenses in Manchuria for the Kempeitai, the Japanese secret police.

- He helped Britain get oil agreements in Persia during the D'Arcy Concession events.

- He secretly entered a Krupp weapons factory in Germany before the war and stole weapon plans.

- He took part in missions of "German sabotage" meant to make the United States join World War I.

- He tried to overthrow the Russian Bolshevik government and save the imprisoned Romanov family.

- Before he died, he supposedly carried the fake Zinoviev letter into the United Kingdom.

British intelligence kept its policy of saying nothing publicly about anything. Yet Reilly's spying successes did get indirect recognition. After a formal recommendation by Sir Mansfield "C" Smith-Cumming, Reilly received the Military Cross on January 22, 1919. This was "for distinguished services rendered in connection with military operations in the field." This vague wording led some writers to wrongly believe Reilly got the medal for brave military actions during World War I. However, most later writers agree the medal was given for Reilly's work against the Bolsheviks in southern Russia.

Andrew Cook, Reilly's most doubtful biographer, says that Reilly's career with the British Secret Intelligence Service has been greatly exaggerated. He claims Reilly was not accepted as an agent until March 15, 1918. He was then let go in 1921 because he tended to act on his own. Nevertheless, Cook admits that Reilly had been a well-known agent for Scotland Yard's Special Branch and the Secret Service Bureau. These were early versions of the British intelligence community. Historian Christopher Andrew, a professor who studies intelligence services, described Reilly's secret service career as "remarkable, though largely ineffective."

Execution

According to Reilly's wife, Pepita Bobadilla, Reilly always wanted to "return to Russia to see if he could not find and help some of his friends whom he believed to be still alive." She said, "This he did in 1925—and never came back." In September 1925 in Paris, Reilly met with Alexander Grammatikov, a White Russian General, a spy expert, and Commander Ernest Boyce from British Intelligence. They discussed how to contact a supposedly anti-Bolshevik group in Moscow called "The Trust." The group agreed that Reilly should go to Finland to see if another uprising in Russia was possible using The Trust. However, The Trust was actually a clever trick created by the OGPU, the Soviet secret police that followed the Cheka.

So, secret agents of the OGPU tricked Reilly into entering Bolshevik Russia. They pretended he would meet with anti-Communist revolutionaries. At the Soviet-Finnish border, Reilly met undercover OGPU agents. They posed as important representatives of The Trust from Moscow. One of these agents, Alexander Alexandrovich Yakushev, later remembered the meeting:

The first impression of [Sidney Reilly] is unpleasant. His dark eyes expressed something biting and cruel; his lower lip drooped deeply and was too slick—the neat black hair, the demonstratively elegant suit. ... Everything in his manner expressed something haughtily indifferent to his surroundings.

Reilly was brought across the border by Toivo Vähä. Vähä was a former Finnish Red Guard fighter who now worked for the OGPU. Vähä took Reilly across the Sestra River to the Soviet side. He then handed him over to the OGPU officers. (In the 1973 book The Gulag Archipelago, Russian writer Alexandr Solzhenitsyn states that Richard Ohola, a Finnish Red Guard, was "a participant in the capture of British agent Sidney Reilly." In the book's glossary, Solzhenitsyn incorrectly guesses that Reilly was "killed while crossing the Soviet-Finnish border.")

After Reilly crossed the Finnish border, the Soviets captured him. They took him to Lubyanka Prison for questioning. When he arrived, Reilly was taken to the office of Roman Pilar. Pilar was a Soviet official who had arrested and ordered the execution of Reilly's close friend, Boris Savinkov, the year before. Reilly was reminded of his own death sentence from a 1918 Soviet court. This sentence was for his part in a plot against the Bolshevik government. While Reilly was being questioned, the Soviets publicly claimed he had been shot trying to cross the Finnish border. Historians debate whether Reilly was harmed while in OGPU custody. Some say he was only psychologically affected, through fake executions meant to break prisoners' spirits.

During OGPU questioning, Reilly lied about his background. He kept pretending to be a British citizen born in Clonmel, Ireland. He did not give up his loyalty to the United Kingdom. He also did not reveal any secret intelligence information. While facing daily questioning, Reilly kept a diary in his cell. He wrote tiny notes on cigarette papers and hid them in the plaster of a cell wall. While his Soviet captors questioned him, he was also studying and writing down their methods. The diary was a detailed record of OGPU questioning techniques. Reilly was confident that such unique information would be useful to the British SIS if he escaped. After Reilly's death, Soviet guards found the diary in his cell. OGPU technicians made photographic enlargements of the notes.

Reilly was executed in a forest near Moscow on Thursday, November 5, 1925. Witness Boris Gudz claimed the execution was watched by an OGPU officer, Grigory Feduleev. Another OGPU officer, Grigory Syroezhkin, fired the final shot into Reilly's chest. Gudz also confirmed that the order to kill Reilly came directly from Stalin. Within months after his execution, British and American newspapers published an obituary notice: "REILLY—On the 28th of September, killed near the village of Allekul, Russia, by S. R. U. Troops. Captain Sidney George Reilly, M. C., beloved husband of Pepita Reilly." Two months later, on January 17, 1926, The New York Times reprinted this notice. Citing unnamed sources in the intelligence community, the paper said Reilly had been involved in the ongoing scandal of the Zinoviev letter. This was a fake document published by a British newspaper during the general election in 1924.

After Reilly's death, there were rumors that he was still alive. Reilly's wife, Pepita Bobadilla, claimed to have proof that Reilly was alive as late as 1932. Others thought that Reilly had switched sides and become an adviser to Soviet intelligence. Despite these rumors, the international press quickly made Reilly a household name. They praised him as a master spy and told many exaggerated stories about his adventures. Newspapers called him "the greatest spy in history" and "the Scarlet Pimpernel of Red Russia." In May 1931, The London Evening Standard published an illustrated series called "Master Spy." It made his many adventures sound exciting and even invented some new ones.

Fictional Portrayals

Soviet Cinema

As a main suspect in the Ambassadors' Plot and a key figure against the Soviet government, Reilly often appeared as a villain in Soviet cinema. In the second half of the 20th century, he was frequently shown as a historical character in films and TV shows made by the Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries. Many different actors played him, including: Vadim Medvedev in The Conspiracy of Ambassadors (1966); Vsevolod Yakut in Operation Trust (1968); Aleksandr Shirvindt in Crash (1969); Vladimir Tatosov in Trust (1976); Sergei Yursky in Coasts in the Mist (1986); and Harijs Liepins in Syndicate II (1981).

Reilly: Ace of Spies

In 1983, a TV show called Reilly, Ace of Spies told the dramatic story of Reilly's adventures. The series was based on Robin Bruce Lockhart's book, Ace of Spies. It won a TV award in 1984. Reilly was played by actor Sam Neill, who was nominated for an award for his performance. Leo McKern played Sir Basil Zaharoff.

A review of the show noted that it was hard to truly show Reilly in 12 hours of television. This was because he was such a mystery. He was supposedly a radical, but he also helped bring down Britain's first Labour government in 1924. This was done using a fake letter, supposedly from a Bolshevik leader, telling British Communists to form secret groups in the armed forces. He was also a charmer who married twice without ending his first marriage. Yet, none of the women he was involved with ever betrayed him. He loved collecting things related to Napoleon and wanted to be a secret power behind the scenes, rather than rule himself.

James Bond

In Ian Fleming, The Man Behind James Bond by Andrew Lycett, Reilly is listed as an inspiration for James Bond. Reilly's friend, Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart, knew Ian Fleming well for many years. Lockhart told Fleming many of Reilly's spy adventures. Lockhart had worked with Reilly in Russia in 1918. There, they were involved in a British Secret Intelligence Service-backed plot to overthrow Lenin's Bolshevik government.

Within five years of his disappearance in Soviet Russia in 1925, the newspapers had made Reilly famous. They praised him as a master spy and told many exaggerated stories about his adventures. Fleming had known about Reilly's legendary reputation for a long time and had listened to Lockhart's stories. Like Fleming's fictional character, Reilly spoke many languages, was interested in the Far East, enjoyed a luxurious life, and was a compulsive gambler. When asked if Reilly's exciting life had directly inspired Bond, Ian Fleming replied: "James Bond is just a piece of nonsense I dreamed up. He's not a Sidney Reilly, you know."

The Gadfly

Voynich published The Gadfly in 1897. It was a popular historical novel set in Italy in the 1840s, when Austria ruled it. The main character is supposedly based on Reilly's early life. Another idea is that Reilly himself tried to be like the revolutionary hero in Voynich's novel. However, historian Mark Mazower noted that "separating fact from fantasy in the case of Reilly is difficult." The theme music for the 1983 TV show is based on the “Romance” part of The Gadfly Suite, which was music by Dmitri Shostakovich for the 1955 Soviet film based on the novel.

See also

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously: 1910–1990

- Xenophon Kalamatiano

Images for kids

-

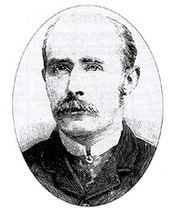

Ethel Voynich, a writer who knew Reilly.

-

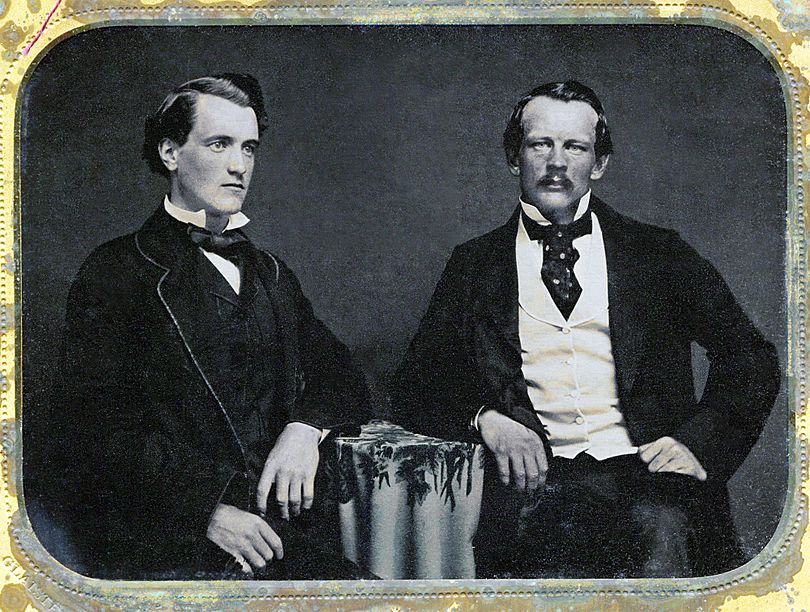

William Melville reportedly helped Reilly create his new identity.

-

A young William Knox D'Arcy in the 1890s

-

Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming, known as "C", recruited Reilly into the British Secret Intelligence Service.

-

Artist Vladimir Pchelin's painting of the August 30, 1918, attempt to kill Vladimir Lenin by Fanya Kaplan.

-

During the Russian Civil War, Reilly worked for British intelligence with General Anton Denikin's White Russian Army.

-

Sam Neill playing Reilly in the TV miniseries Reilly, Ace of Spies (1983).

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |