Simón Bolívar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Simón Bolívar

|

|

|---|---|

A portrait of Simón Bolívar from 1922

|

|

| 1st President of Colombia | |

| In office 16 February 1819 – 27 April 1830 |

|

| Preceded by | Estanislao Vergara y Sanz de Santamaría |

| Succeeded by | Domingo Caycedo |

| President of Peru | |

| In office 10 February 1824 – 27 January 1827 |

|

| Preceded by | José Bernardo de Tagle |

| Succeeded by | José de La Mar |

| 1st President of Bolivia | |

| In office 6 August 1825 – 29 December 1825 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Antonio José de Sucre |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 July 1783 Caracas, Captaincy General of Venezuela |

| Died | 17 December 1830 (aged 47) Santa Marta, Gran Colombia |

| Resting place | National Pantheon of Venezuela |

| Nationality |

|

| Spouse | |

| Domestic partner | Manuela Sáenz |

| Signature |  |

Simón Bolívar (born July 24, 1783; died December 17, 1830) was a brave military and political leader from Venezuela. He is famous for leading the fight for independence against the Spanish Empire. He helped free the countries we know today as Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia. Because of his incredible achievements, he is known as El Libertador, which means The Liberator.

Bolívar was born into a very wealthy family in Caracas, Venezuela. He grew up surrounded by new ideas about freedom and people's rights. He dreamed of a South America that was free from Spanish rule and united as one great nation. For over 20 years, he led armies across the continent, fighting many battles to achieve this dream.

In his final years, Bolívar was sad to see some of the new countries fight among themselves instead of staying united. He died of tuberculosis in 1830. Today, he is remembered as a hero and a national icon in many South American countries. The nations of Bolivia and Venezuela are even named after him.

Early Life and Education

Simón Bolívar was born on July 24, 1783, in Caracas, which was then part of the Spanish Empire. His full name was Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios. His family was one of the richest in Venezuela.

Even though he had many privileges, his childhood was also difficult. His father died when he was only two years old, and his mother died when he was nine. After his parents passed away, he was cared for by his grandfather and uncles. A woman named Hipólita, who was an enslaved African servant in his household, played a very important role in raising him. Bolívar loved her very much and saw her as a mother figure.

A Promise in Europe

As a boy, Bolívar had several teachers, including the famous educator Simón Rodríguez. Rodríguez taught him many important ideas about liberty and justice. When he was a teenager, his uncles sent him to Spain to continue his studies.

In Madrid, he met and married María Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaysa. They moved back to Venezuela, but sadly, she died from yellow fever less than a year later. Bolívar was heartbroken by her death.

After this tragedy, he traveled through Europe. In Rome, he made a famous promise on a hill called Mons Sacer. He swore that he would not rest until he had freed South America from Spanish rule. This moment became a turning point in his life.

The Wars for Independence

Bolívar's military career began in 1810 when Venezuela first declared its independence. For the next two decades, he would lead the fight against the Spanish Royalists, who were loyal to the King of Spain.

First Fights for Venezuela

The first attempt to create a Republic of Venezuela failed. In 1812, a powerful earthquake hit Venezuela, causing a lot of damage and confusion. Many people thought it was a punishment from God for rebelling against Spain. The Spanish forces, led by Juan Domingo de Monteverde, took back control of the country.

Bolívar had to flee Venezuela. He went to New Granada (modern-day Colombia), where he wrote the Cartagena Manifesto. In this document, he explained why the first republic had failed and called for all of South America to unite against Spain.

In 1813, Bolívar led a small army back into Venezuela in a surprise attack known as the Admirable Campaign. In just a few months, he freed a large part of the country and entered Caracas as a hero. It was then that he was first called El Libertador. However, the fight was far from over. Royalist forces, led by a tough leader named José Tomás Boves, fought back and defeated the second Venezuelan republic in 1814.

Help from Haiti and Return to the Fight

Forced into exile again, Bolívar traveled to Jamaica and then to Haiti. In Haiti, he met President Alexandre Pétion, who agreed to help him. Pétion gave Bolívar money, weapons, and soldiers. In return, Bolívar promised to free all the enslaved people in the lands he liberated.

With this new support, Bolívar returned to Venezuela in 1816 and started the third and final push for independence. He established a base in the city of Angostura (now Ciudad Bolívar) and began to unite the different patriot armies under his command.

Crossing the Andes

One of Bolívar's most brilliant military actions was his campaign to liberate New Granada in 1819. While the Spanish army was expecting him to attack in Venezuela, Bolívar decided to do something completely unexpected.

He led his army of about 2,000 soldiers on a difficult journey across the freezing and dangerous Andes mountains. Many soldiers died from the cold and exhaustion, but the survivors managed to surprise the Spanish army. On August 7, 1819, Bolívar won a decisive victory at the Battle of Boyacá. This victory secured the independence of New Granada.

The Dream of Gran Colombia

After freeing Venezuela and New Granada, Bolívar worked to unite them. On December 17, 1819, the Republic of Colombia, later known as Gran Colombia, was created. This new nation included the territories of modern-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. Bolívar was elected its first president.

His dream was to create a single, powerful nation in South America that could stand alongside other great nations of the world.

Liberating Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia

Bolívar's fight for freedom was not over. He next turned his attention to the south. His best general, Antonio José de Sucre, led an army into Ecuador. In 1822, Sucre won the Battle of Pichincha, which freed Ecuador and allowed it to join Gran Colombia.

The final strongholds of Spanish power were in Peru and Upper Peru. Bolívar traveled to Peru and was named its dictator so he could lead the army. In 1824, he and Sucre won two major battles:

- The Battle of Junín (August 6, 1824), where Bolívar's cavalry defeated the Spanish.

- The Battle of Ayacucho (December 9, 1824), where Sucre's army completely destroyed the remaining Spanish forces. This battle is seen as the end of the Spanish American wars of independence.

In 1825, the region of Upper Peru declared its independence. In honor of Bolívar, the new country was named Bolivia, and he was asked to write its first constitution.

Final Years and Death

In his last years, Bolívar grew sad and disappointed. His dream of a united Gran Colombia was falling apart. Different regions began to argue, and leaders like José Antonio Páez in Venezuela wanted to break away. The political fighting made it impossible to govern the large republic.

Tired and in poor health, Bolívar resigned from the presidency in 1830. He planned to travel to Europe but died of tuberculosis in Santa Marta, Colombia, on December 17, 1830. He was 47 years old.

His famous last words were, "all who have served the Revolution have plowed the sea," meaning he felt that all his hard work for unity had been for nothing.

Legacy

Simón Bolívar is remembered as one of the most important figures in South American history. He is often called the "George Washington of South America" because he helped create new nations.

- The countries of Bolivia and Venezuela (officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela) are named in his honor.

- The currencies of both countries are also named after him (the boliviano and the bolívar).

- Statues, cities, and streets all over the world are named after him, celebrating his legacy as El Libertador.

Bolívar's ideas about freedom, unity, and government continue to influence politics and culture in Latin America today.

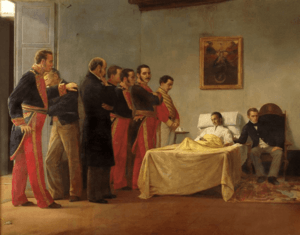

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Simón Bolívar para niños

In Spanish: Simón Bolívar para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |