Stane Street (Chichester) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

[[File:|175x70px|alt= shield]] Stane Street |

|

|---|---|

| Roman Road | |

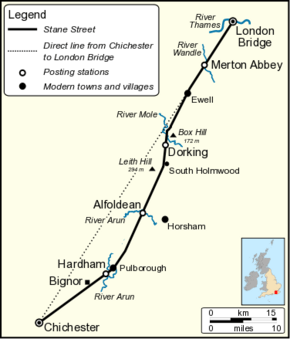

Map of Stane Street showing the direct line from London Bridge to Chichester and the actual course of the road. The positions of Bignor Villa and the four posting stations (the northern two supposed) are shown. The modern courses of the three major rivers crossed by the road are also displayed.

|

|

| Route information | |

| Length | 91 km (57 mi) |

| History | Constructed in 1st century AD, several sections remain in use today |

| Time period | Roman Britain |

| Major junctions | |

| From | Londinium (London) |

| To | Noviomagus Reginorum (Chichester) |

| Location | |

| Counties: | Greater London, Surrey, West Sussex |

| Road network | |

|

|

Stane Street is the modern name for an ancient Roman road in southern England. It was about 91 kilometers (56 miles) long. This road connected Londinium (which is now London) to Noviomagus Reginorum (which is now Chichester).

We are not sure exactly when Stane Street was built. But old pottery and coins found along its path show it was used by 70 AD. It might have been built very early in the Roman occupation of Britain, possibly between 43 and 53 AD.

Stane Street is a great example of how the Romans built their roads. A straight road from London Bridge to Chichester would have gone over very steep hills. These include the North Downs, Greensand Ridge, and South Downs. So, the Romans planned the road to use a natural gap in the North Downs, made by the River Mole. It also went around the high ground of Leith Hill. Then, it followed flatter land in the River Arun valley to Pulborough.

The road was only perfectly straight for the first 20 kilometers (12 miles) from London to Ewell. Even so, the road never went more than 10 kilometers (6 miles) away from a direct line between London Bridge and Chichester.

Today, you can still easily find the Roman road on modern maps. Parts of it are now followed by major roads like the A3, A24, A29, and A285. However, much of the road in Surrey has either disappeared or is now just bridlepaths. You can see old earthworks (raised ground) from the road in many places where modern roads don't cover it. Some parts of Stane Street are even protected as scheduled monuments. This includes a well-preserved section near Ashtead.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Stane" is an old way of spelling "stone." This name was often used to tell paved Roman roads apart from muddy local tracks. The road's name was first written down as Stanstret in the 1270s. Some old books call it 'Stone Street.' We don't know what the Romans originally called this road.

How Do We Know Its Age?

Archaeologists have found many pieces of pottery from the first century along the road. This includes special pottery called samian ware from the time of Emperor Claudius (41–54 AD). The oldest coins found are from the reigns of Claudius, Nero (54–68 AD), and Vespasian (69-79 AD). This tells us the road was definitely in use by 60 to 70 AD. It might have been built even earlier, between 43 and 53 AD.

Later coins found show the road was used for a long time. These include coins from Titus (79–81 AD), Domitian (81–96 AD), Hadrian (117–138 AD), and even Constantine the Great (306–337 AD).

How Was the Road Planned?

A straight line from London Bridge to Chichester would have gone over Ranmore Common (200 meters or 656 feet high) and Holmbury St Mary (260 meters or 853 feet high). Such steep slopes would have been very hard for carts and wagons. So, the Romans designed the road to cross the North Downs through a natural gap made by the River Mole. It also went around the high ground of Leith Hill.

The builders also thought about the type of ground. The road leaves the straight line at Ewell to go onto the well-drained chalk of the North Downs. This was better than staying on the London Clay, which can get very muddy. The chosen path also made it easier to climb the South Downs at Bignor. It avoided crossing the steep River Lavant valley.

We don't have any records that tell us exactly how the Romans surveyed or planned the road's path.

How Was It Built?

For most of its length, Stane Street had a raised central part called an agger. This was like a high bank where the road surface was laid. There were ditches on both sides. The Romans used local materials to build the road. Sometimes, they brought in stone from other places.

The agger was often made of layers of sand and gravel. On top, they put large flint stones or sandstone. The very top layer was smaller flint, sand, or gravel. This top layer was usually about 30 centimeters (1 foot) thick in the middle. It was also shaped with a camber, meaning it was higher in the middle to let water drain off.

In some places, like near Merton Priory, the road surface was made of rounded flints and gravel mixed with sand and mud. Near Mickleham Downs, Stane Street was built with water-worn pebbles directly on the chalk. This section was even called 'Pebble Lane.' Near the Alfoldean station, the road was made of iron slag topped with sandstone slabs.

The paved part of the road was usually about 7.4 meters (24 feet) wide. This is wider than the average Roman road in Britain, which was about 6.51 meters (21 feet) wide. The distance between the outer ditches also changed. It was 12-16 meters (39-52 feet) at Merton Priory and 27 meters (89 feet) at Westhampnett.

Rest Stops Along the Way

The Romans had special rest stops called mansiones along their roads. These were usually every 15 to 20 kilometers (9 to 12 miles). Messengers could change horses here, and travelers could rest. These stops were typically square-shaped, fortified sites about 1 hectare (2.5 acres) in size.

Two mansiones have been found on Stane Street: at Alfoldean and Hardham. Both were near places where the road crossed the River Arun.

The Alfoldean mansio was explored in 2006 by a TV show called Time Team. They found the remains of a two-story building with a courtyard, and other buildings too. The site was surrounded by huge ramparts and ditches that were 4 meters (13 feet) wide and deep. These were built around 90 AD. The ditches were filled in by the mid-third century. The team thought this site was a center for managing and taxing the local iron industry.

A special survey in 1997 looked at the Hardham mansio. It showed the station was roughly square, covering about 1.4 hectares (3.5 acres). Part of it was destroyed when a railway was built. But we can still see where the north and south gates were, and parts of the outer ditches. Old burials from the Iron Age and Roman times were found there. The Hardham station was probably no longer used by the end of the second century AD.

Because Stane Street was so long, there should have been two more mansiones. Places like Merton Priory and Dorking are thought to be likely spots. However, any remains would now be hidden under modern buildings. Other possible locations for these rest stops include Ewell, Burford Bridge (where the road crossed the River Mole), and Pixham.

The Road's Path

London Bridge to Ewell

The northern part of Stane Street, from London Bridge to Ewell, is the only section that follows a direct line to Chichester. Even here, the builders made small changes to avoid difficult ground. From the south bank of the River Thames, the A3 follows the route to Clapham Common. Then, the A24 follows it to Ewell.

The Roman London Bridge was about 60 meters (197 feet) east of the modern bridge. From there, the road went southwest. But between the Borough and Elephant and Castle tube stations, it moved slightly east. This was probably to avoid marshy ground. It then continued southwest as Kennington Park Road and Clapham Road. The exact path around Clapham Common is not clear.

Stane Street crossed the River Wandle near Merton Priory. The river has changed course since Roman times. The original crossing point was likely a ford near Colliers Wood tube station. Digs in the late 1990s showed the road was about 14 meters (46 feet) wide. Its surface was mainly pebbles pressed into mud and gravel. Two metal brooches, likely worn by important people, were found there.

A rare Roman burial mound, called a barrow, still exists in Morden Park. It's a circular mound about 32 meters (105 feet) wide and 3.4 meters (11 feet) high. It is about 350 meters (383 yards) west of the road. From Morden, Stane Street goes through Sutton Common and forms the northern border of Sutton. The name 'Sutton' comes from Old English words meaning "the south enclosure," which might refer to its location near the road. Stane Street runs along the western edge of Nonsuch Park as it enters Surrey, northeast of Ewell.

Ewell to Burford Bridge

From the first to the fourth centuries AD, Ewell was a large Roman-British town. Stane Street comes from the northeast, leaving muddy ground and briefly moving onto better-draining sandy soil. Near Church Street, the road turns 23 degrees south. This helped it reach the Upper Chalk of the North Downs faster. Some think the turn was sharper than needed, possibly to avoid the Hogsmill Spring, which might have been a special place for local tribes. Another turn happens where the Epsom to Sutton railway line crosses the road.

The section from Thirty Acres Barn, Ashtead, to Mickleham Downs is very well preserved. It is a scheduled monument. A survey in 2020 showed that Stane Street was built over an older field system. It's not clear if these fields were still used when the road was built. There's a lot of evidence of Bronze Age and Iron Age activity on Mickleham Downs. This suggests the Romans might have used and straightened an existing old trackway to create this part of Stane Street.

The confirmed route reaches the southwest corner of Mickleham Downs near Juniper Hall Field Centre. But south of there, the path is less certain. Stane Street is thought to have followed the same route as the modern B2209. This road's surface has been worn down over centuries, creating the sunken lane you see today. The footpath on the west side of the modern road might show how much the original Roman road surface has worn away.

Stane Street crossed the River Mole using a ford near the modern Burford Bridge. Digs in 1937 found a "flint-surfaced approach to [a] ford at low level having all the signs of Roman workmanship."

The Route Through Dorking

We haven't found clear proof of the road's path in the 5-kilometer (3-mile) 'gap' between the Mole crossing and North Holmwood. But Stane Street is thought to have gone through Dorking, which was a Roman-British settlement. In the 1960s, historian Ivan Margary suggested the road went straight to the town center from Burford Bridge. This path would be under the current Ashcombe School buildings. However, digs in the mid-2000s at Westhumble and Denbies Wine Estate found no trace of the road there. Most experts now think this part of Stane Street is likely under the A24 dual carriageway.

Digs in the 1970s and 1980s found parts of a road in Dorking. But they couldn't say for sure if it was Stane Street. It seems likely that the A2003 follows the general route as it left the town to the south. The confirmed path reappears in the south of North Holmwood.

Based on the distance from Alfoldean (about 18.3 kilometers or 11.4 miles to the town center), there should have been a mansio in the Dorking area. Many digs and accidental finds along High Street have turned up Roman coins, pottery sherds, and other items. These show that Romans were present there. There was also a Roman villa nearby at Abinger Hammer.

Both Margary and writer Hilaire Belloc thought the mansio was at the western end of High Street. But digs in 2013, during the rebuilding of a supermarket, didn't find any major Roman items to support a mansio or Stane Street in that area. Other places suggested for the mansio include Burford Bridge (where the name 'bur' might mean a fortified site) and Pixham (where there might have been a Roman villa).

North Holmwood to Pulborough

As Stane Street leaves Dorking, the ground changes from sandy soil to Weald Clay, which doesn't drain well. From North Holmwood to Ockley (about 5.5 kilometers or 3.4 miles), the exact route has been confirmed by digs. Much of this section is still in good condition, though it's buried. The top surface seems to have been removed, probably to get stone for local buildings. A lot of flints were found in the remaining road core. These flints don't naturally occur in Weald Clay. This suggests they were brought from north of Dorking, meaning this part of the road was built from north to south.

The old Saxon and medieval road from Dorking to the south avoids this section. It climbs the eastern slopes of Leith Hill to Coldharbour, then goes down to Ockley. This later route is longer and steeper, climbing to 225 meters (738 feet). But it stays on better-draining ground. It's possible that once the Roman road's top surface was taken, the section on Weald Clay became unusable in wet weather.

The road changes direction west of South Holmwood. It then follows a line aimed from London Bridge to Pulborough. The only big change is at Okewood Hill. Here, the road loops west for about 200 meters (219 yards) to cross a small stream at a good ford. The A29, which follows the route through Ockley, also leaves the direct line here but turns east instead. This part of Stane Street is mostly flat, except for a hill at Rowhook, which is 86 meters (282 feet) high. The A29 avoids this hill.

Just south of the steep slope from Rowhook through Roman Woods, the road crossed the River Arun. Some of the wooden piles that supported the bridge are still in the riverbed. Roman tiles and cut stone in the riverbed show that stone bridge piers were built on top of the piles. The Alfoldean mansio is about 30 meters (33 yards) south of the bridge site. A small settlement grew up along the 300-meter (328-yard) stretch of road just south of the rest stop.

The 16-kilometer (10-mile) section south from Alfoldean to Pulborough is covered by the A29. The general path is a straight line. But the modern road sometimes moves away from the original Stane Street, especially around Slinfold. The modern roads also curve through Billingshurst. However, the Roman road is thought to have done the same to fit the local landscape and ground conditions.

Pulborough to Chichester

Stane Street crossed the River Arun a second time at Pulborough Bridge. The original Roman crossing is gone. But a medieval-style bridge was built in 1777 on the same spot. The road was built on a 580-meter (634-yard) raised path to cross marshy ground south of the river. The modern A29 runs over this path.

The Sussex Greensand Way Roman road to Lewes joined Stane Street at the Hardham mansio, southwest of Pulborough. From here, Stane Street turns to go straight towards the east gate of Chichester. It passes the famous Roman villa at Bignor. It makes a small detour from the direct line to climb the South Downs at Bignortail Wood. You can see the road as a terrace (a flat, raised strip) cut into the steep hillside as it climbs towards Bignor Hill.

As the road crosses Gumber Down, the agger becomes very narrow, only about 1 meter (3 feet) wide. But it is often more than 1.5 meters (5 feet) high. This unique shape is thought to be from later repairs after the Roman times. These repairs turned Stane Street into a clear boundary bank. A dig in 1913 showed that the road was much wider before. The distance between the outer ditches was 28 meters (92 feet).

Through Eartham Woods, where the Monarch's Way walking path follows the route, the flint surface of the well-preserved road is visible. The trees are mostly cut back to the old boundary ditches. The A285 joins the route on the west side of Eartham Woods. But it leaves the path almost right away to avoid climbing Halnaker Hill. It then rejoins the Roman road for the last 7 kilometers (4 miles) into Chichester.

Some people think the section of road between Chichester and Hardham was the first part of Stane Street to be built. Based on archaeological finds, the Romans might have straightened and improved an existing Iron Age trackway here.

Other Roman Roads Connected to Stane Street

At least five other Roman roads connected to Stane Street:

- The London to Brighton Way road split off at Kennington Park. It went through Croydon, Godstone, Haywards Heath, and Burgess Hill to cross the South Downs at Clayton.

- From Rowhook, a road went northwest to Farley Heath. This road passed through a Roman temple site.

- North of Pulborough, another road branched off southeast. It met the Greensand Way at Wiggonholt. It's not clear if it continued beyond this point towards Storrington.

- The Sussex Greensand Way splits from Stane Street at the Hardham mansio. It follows a well-drained sandstone ridge east to Lewes.

- At Westhampnett, near the Rolls-Royce factory, the Roman coastal road branched off. This road went through Broadwater, Sompting, Lancing (along a road still called The Street), and part of the Old Shoreham Road (the A270) to Novus Portus (near modern Portslade).

Why the Road Was Used Less

Stane Street's importance for the Roman army seemed to decrease in the second half of the Roman occupation of Britain. The mansio at Hardham was probably no longer used by the end of the second century AD. Also, Stane Street is not mentioned in the third-century Antonine Itinerary. This suggests that the preferred route from Chichester to London was then through Winchester.

However, Stane Street continued to be an important trade route until at least the early fourth century. Goods like pottery were moved along the road.

After the end of Roman rule in Britain, how much the Anglo-Saxons used and kept up the road changed. Londinium was no longer a city by the fifth century. But its new version, Lundenwick, was big enough to keep the road between Ewell and Southwark in use. When Sussex became a political area, the north-south roads across the Weald to the old Roman capital became less important. So, much of the rest of Stane Street was abandoned.

The section between Alfoldean and Pulborough, which connects Billingshurst with two river crossings, was likely kept up as a local road. The A29 follows this part today. Similarly, the 8-kilometer (5-mile) stretch east of Chichester was useful for climbing onto the South Downs. The A285 follows this part today.

In other places, the road was used very little. It was probably dug up in the years after Roman rule ended to get stone for local buildings. Especially where the road was on Weald Clay, removing the top surface likely made it unusable in wet months. Later, farming or city growth completely removed any traces of it.

Daniel Defoe, who wrote Robinson Crusoe, described the disappearance of Stane Street in his travel book A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain (1724–1727). He wrote about how the roads in Sussex, including Stane Street, had disappeared. He said the country was in "utmost distress" because of bad roads.

How We Learned About Stane Street

People knew about Stane Street from Anglo-Saxon times until much later. For example, William Camden mentioned it in his book Britannia in 1586. But no one really studied the road in detail until the early 1900s.

The writer Hilaire Belloc published a book called The Stane Street: A monograph in 1913. He tried to map out the entire road. Belloc was not a trained surveyor, so his work on the northern part of the road had some mistakes. W. A. Grant, a former captain in the Royal Engineers, tried to fix these mistakes in his review in 1922.

Digs by amateur archaeologist S. E. Winbolt, described in his book With a spade on Stane Street (1936), greatly helped us understand the road. His work was the basis for the chapter on Stane Street in Ivan Margary's book Roman Ways in the Weald (1948). Stane Street is given the Margary number 15.

Protecting Stane Street

Several parts of Stane Street, including the mansiones at Alfoldean and Hardham, are protected as scheduled monuments.

A 32-meter (105-foot) section of Stane Street near South Holmwood was restored by archaeologist S. E. Winbolt in 1935. This section was covered with grass to protect it for the future.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |