Roman roads in Britannia facts for kids

Imagine a time when Britain had no paved roads! That's how it was before the Romans arrived. Roman roads in Britannia were super important. The Roman army built them over almost 400 years (from AD 43 to 410). These roads helped the Romans control their new province.

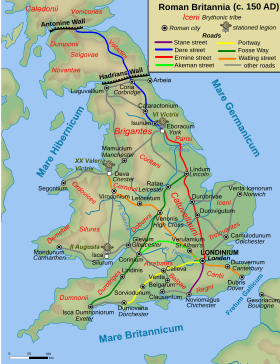

It's thought that the Romans built about 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of main roads. Most of this network was finished by AD 180. At first, these roads were for moving soldiers and supplies quickly. But soon, they became vital for trade, business, and transporting goods across the country.

Many Roman roads were still used every day for hundreds of years after the Romans left Britain in 410. Some of these old routes are even part of the UK's modern road network today. Other parts have disappeared or are only interesting to historians and archaeologists.

After the Romans, Britain didn't build new paved highways until the early 1700s. The Roman road network was the only national road system in Britain for a very long time. It wasn't until the early 1900s that a new government department took over managing roads.

Contents

Building Britain's First Highways

Before the Romans came, people in Britain mostly used dirt paths. These paths, some very old, often followed high ridges across hills. They were not paved or specially built. However, some British tribes had started to build their own roads in the 1st century BC.

Starting in AD 43, the Romans quickly began building a national road network. Roman army engineers usually planned and built these roads from scratch. They connected important places, like military bases and towns, using the most direct routes possible. Main roads were covered with gravel or paving stones. They had strong bridges made of stone or wood. Along the way, there were special stops where travelers or soldiers could rest.

The roads were designed to be waterproof. This meant people could travel on them in all seasons and weather. After the Roman soldiers left in 410, the road system slowly fell apart. Many parts were abandoned and lost. But the Anglo-Saxons kept using some sections. These became important routes in Anglo-Saxon Britain.

How the Roman Road Network Grew

The first Roman roads were built between AD 43 and 68. They linked London to the invasion ports like Chichester and Richborough. They also connected London to early army bases at Colchester, Lincoln, Wroxeter, Gloucester, and Exeter. The Fosse Way, running from Exeter to Lincoln, was also built then. It connected these bases and marked the edge of the early Roman province.

Between AD 69 and 96, roads were extended. They reached new army bases at York, Chester, and Caerleon. By AD 96, more roads were built from York to Corbridge. Others went from Chester to Carlisle and Caernarfon. This happened as Roman rule spread across Wales and northern England. The Stanegate military road, from Carlisle to Corbridge, was built under Emperor Trajan (ruled 98–117). It followed the path of what would become Hadrian's Wall, built by Emperor Hadrian in 122–132.

Scotland was mostly outside the Roman province of Britannia. The Romans never fully conquered the whole island. They did try, and they built forts in the lowlands from about AD 80 to 220. They even built the Antonine Wall in 164. This wall stretched across Scotland, from the Firth of Clyde to the Firth of Forth. It was held for about twenty years.

The main Roman routes from Hadrian's Wall to the Antonine Wall were built around AD 120. These included roads from Corbridge to Cramond (near Edinburgh) and from Carlisle to Bothwellhaugh. There was also a road beyond the Antonine Wall to Perth.

Over time, other roads were built for trade, not just for the army. For example, in Kent and Sussex, roads led from London to important iron-mining areas. In East Anglia, roads like the Peddars Way and the Fen Causeway were built. These eastern and southern roads became important for defense from the 3rd century onwards. They linked to coastal forts that protected against Saxon raiders coming by sea.

How Roman Roads Were Built

The Romans used standard road-building methods they had developed in Europe. First, they cleared a wide strip of land. This strip could be from 25.5 meters (86 feet) to 100 meters (338 feet) wide. A main road in Britain was usually 5 to 8 meters (16 to 26 feet) wide. Watling Street was 10.1 meters (33 feet) wide, while the Fosse Way was about half that.

In the middle, they built a raised path called an agger. They first removed soft topsoil. Then, they used the best local materials, often sand or gravel, to build up the agger. The areas on either side of the agger were for people walking or animals. Sometimes, these side paths were also lightly graveled. Deep ditches often ran alongside the agger to drain rainwater and keep the road dry.

The road surface had two layers. The bottom layer was made of medium to large stones. On top of this was a running surface of smaller flint and gravel, pressed down firmly. About a quarter of Roman roads had large stones at the very bottom. This was more common in the north and west where stone was easy to find. Some important roads in Italy used volcanic mortar to bind the stones. A few sites in Britain show evidence of concrete or limestone mortar. In areas where iron was produced, like the Weald, road surfaces were made from iron slag. The average depth of the road material was about 51 cm (20 inches). But it could vary a lot, from just 10 cm (4 inches) to up to 4 meters (13 feet) in some places, likely built up over many years.

The Roman army built the main roads. After construction, special imperial officials were in charge of repairs and upkeep. Local county authorities probably paid for the maintenance. Roads were sometimes completely resurfaced or even rebuilt. For example, Emperor Augustus rebuilt and widened a major road in northern Italy two centuries after it was first built.

After the Roman government and troops left Britain in 410, regular road maintenance stopped. Repairs became rare and unplanned. Even without national management, Roman roads remained key transport routes in England throughout the Middle Ages. New paved highways weren't systematically built again until the early 1700s.

Finding Roman Roads Today

Many Roman roads today are worn down or covered by later surfaces. Some well-preserved sections, like Wade's Causeway in Yorkshire, are thought to be original Roman surfaces. However, it's hard to be completely sure. In many places, new roads were built right on top of Roman roads in the 1700s. Where they weren't built over, farmers often ploughed them up. Some stones were even taken to build new roads.

You can still find many parts of Roman roads today. They often look like overgrown footpaths through woods or common land. For example, a section of Stane Street goes through Eartham Wood in the South Downs. These paths are often marked on maps. Peddars Way in Norfolk is a Roman road that is now a long-distance walking path.

The Romans had special stations along their roads, like modern motorway service areas. About every 4 miles (6.4 km), there was a mutatio. This was a place where messengers could change horses and get refreshments. Fast riders could travel about 20 mph (32 km/h). This meant an urgent message from York to London (200 miles or 320 km) could arrive in just 10 hours! It's hard to find mutationes today because they were small.

About every 12 miles (19 km), there was a mansio. This was a larger inn, like a hotel, with big stables, a tavern, rooms for travelers, and sometimes even bath-houses. Mansiones also housed soldiers who patrolled the roads. These soldiers checked people's identities, travel permits, and goods.

Mansiones might also have been where officials collected the portorium. This was a tax on goods traveling on public roads, usually 2 to 2.5 percent of their value. This tax was collected at fixed points, probably near mansiones. At least six mansiones have been found in Britain, like the one at Godmanchester.

Mutationes and mansiones were key parts of the cursus publicus. This was the Roman Empire's postal and transport system. It carried government officials, money, and official messages. Private individuals could use it too, with special permission and a fee. The Vindolanda tablets, letters found near Hadrian's Wall, show how this system worked in Britain.

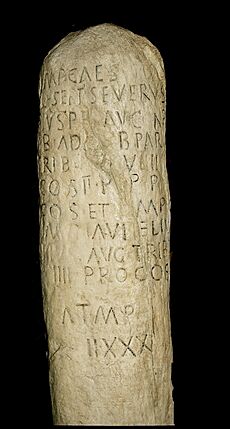

Milestones were also common. These were stone pillars, usually 2 to 4 meters (6.5 to 13 feet) tall. Most just named the current Emperor and the distance to a town. Only a few give extra details, like who paid for the road repair. One milestone records that Emperor Caracalla "restored the roads, which had fallen into ruin and disuse through old age."

Old Roman maps and travel guides also help us learn about roads in Britain. The most important is the Antonine Itinerary, from the late 3rd century. It lists 14 routes on the island.

How Roman Roads Got Their Names

We don't know the original Roman names for most roads in Britain. This is different from roads in Italy and other Roman provinces. In Britain, most major Roman routes have Welsh, early Anglo-Saxon, or later Middle English names. These names were given after the Romans left.

For example, the Anglo-Saxons called the road from Dover to Wroxeter, through London, Watlingestrate. This was one of four old Roman roads named as public rights of way in the early 11th century.

Official Roman road names often came from the Emperor who finished them. For instance, the Via Traiana in Italy was named after Emperor Trajan. The Dover to London part of Watling Street was started after the Roman invasion in AD 43. So, it might have been called the Via Claudia after Emperor Claudius.

The Fosse Way, between Exeter and Lincoln, might have a name linked to a Roman word. Fossa is Latin for "ditch." But this was probably a popular name, not an official one. Generally, Roman roads in Britain were named after Anglo-Saxon giants and gods. For example, Wade's Causeway is named after Wade from Germanic and Norse mythology.

English place names still show the influence of the Anglo-Saxons. As these people moved across Britain, they found the old Roman roads. Many towns were built on or near these roads. The word "street" in a town name often means it was on a Roman road (like Watling Street). Words like "strat-", "strait-", or "streat-" also show a town was near an old Roman highway. For example, Stretham means "homestead on a Roman road."

Key Roman Road Routes

The first Roman roads were built by the army for military communication. So, they mainly connected army bases. By AD 80, three important cross-country routes linked the main army bases:

- Exeter (Isca) – Lincoln (Lindum)

- Gloucester (Glevum) – York (Eboracum)

- Caerleon (Isca) – York, passing through Wroxeter (Viroconium) and Chester (Deva)

Later, many other routes and branches were added to this main network.

After Boudica's Revolt, London (Londinium) became very important. It had the main bridge over the River Thames. This connected the northern and western army bases to the ports in Kent that linked to Europe. Six main roads were built from London to join the existing network:

- London – Canterbury (Durovernum). At Canterbury, this road split into four major branches to important Roman ports:

- Canterbury – Richborough Castle (Rutupiae)

- Canterbury – Dover (Portus Dubris)

- Canterbury – Lympne (Portus Lemanis)

- Canterbury – Reculver (Regulbium)

- London – Chichester (Noviomagus), a port.

- London – Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum). At Silchester, this road split into three major branches:

- Silchester – Portchester (Portus Adurni), a port, via Winchester (Venta) and Southampton (Clausentum)

- Silchester – Old Sarum (Sorviodunum), connecting to Exeter and Dorchester (Durnovaria)

- Silchester – Caerleon, home of the 2nd legion, via Gloucester

- London – Chester, home of the 20th legion, via St Albans (Verulamium), Lichfield (Letocetum), and Wroxeter. It continued to Carlisle (Luguvalium) on Hadrian's Wall.

- London – York, home of the 9th and 6th legions, via Lincoln. It continued to Corbridge (Coria) on Hadrian's Wall.

- London – Colchester (Camulodunum), continuing to Caistor St Edmund (Venta).

Famous Roman Roads and Their Modern Paths

Many Roman roads are still visible today or form the basis of modern roads. Here are a few well-known examples:

- Ackling Dyke

- Route: Old Sarum to Badbury Rings

- Modern Link: Part of the A354 near Woodyates

- Akeman Street (from St Albans)

- Route: St Albans (Verulamium) to Cirencester (Corinium)

- Modern Link: Sections of the A41 from Bicester to Tring

- Dere Street

- Route: York (Eboracum) to the Antonine Wall in Scotland

- Modern Link: Parts of the A59 and A1(M)

- Fosse Way

- Route: Exeter (Isca Dumnoniorum) to Lincoln (Lindum)

- Modern Link: Parts of the A37, A429, B4455, and A46

- Peddars Way

- Route: Holme-next-the-Sea to Knettishall Heath in Norfolk

- Modern Link: Now a long-distance footpath, no modern road counterpart.

- Watling Street

- Route: The Kentish ports (like Richborough or Dover) to Wroxeter (Viroconium)

- Modern Link: Sections of the A2, A207, and A5

Some of these modern road sections lie directly on top of the old Roman roads. These are often marked on maps. It's important to remember that some names, like "Akeman Street" (from Wimpole) or "Via Devana," were invented by historians later. Also, some ancient paths, like Wade's Causeway, are still being studied to confirm if they were truly Roman roads.

See also

- Margary numbers

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |