Van Cortlandt House facts for kids

|

Van Cortlandt House

|

|

The mansion in 2008

|

|

| Location | Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx, New York City |

|---|---|

| Area | 192 acres (78 ha) |

| Built | 1748 |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 67000010 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | December 24, 1967 |

| Designated NHL | December 24, 1976 |

The Van Cortlandt House, also called the Van Cortlandt Mansion, is the oldest house still standing in the Bronx, New York City. It's located in the southwest part of Van Cortlandt Park. Today, it's a historic house museum known as the Van Cortlandt House Museum.

A man named Frederick Van Cortlandt started building the house in 1748, and it was finished in 1749. It's a two-and-a-half-story building designed in the Georgian style. It has stone walls and fancy Georgian-style rooms inside. The Van Cortlandt family lived here for 140 years. Then, in 1897, it opened as a museum for everyone to visit.

The land for the house was bought by Jacobus Van Cortlandt in the 1690s. Frederick, Jacobus's son, began building the house but passed away before it was done. His son, James, inherited it. During the American Revolutionary War, both British and American soldiers used the house at different times. The house stayed in the Van Cortlandt family until the late 1800s. In 1888, New York City bought the house to create Van Cortlandt Park. At first, it was used as a police station. But in 1896, a group called the Society of Colonial Dames of the State of New York took over. They opened it as a museum on May 28, 1897. The house has been updated and cared for over the years, with big renovations in the 1960s and 1980s.

The house has an L-shape, with parts extending to the south and east. A caretaker's house was added later to the north. The outside of the mansion looks simple, but it has special brick decorations above the windows. These decorations show faces that look like members of the Van Cortlandt family. Inside, there's a kitchen in the basement, living rooms, an entry hall, and a dining room on the first floor. Bedrooms are on the second and third floors. The museum often hosts events, tours, and educational programs. People have praised both the museum's exhibits and the house's beautiful design. The house's outside and inside are protected as New York City designated landmarks, and it's also a National Historic Landmark.

Contents

Where is the Van Cortlandt House?

The Van Cortlandt House is in the southwest part of Van Cortlandt Park. This is near the Riverdale neighborhood in the Bronx, New York City. It's surrounded by different parts of the park. To the north is the Parade Ground, to the west is the Memorial Grove, and to the south are a swimming pool and stadium. To the east, you'll find a burial ground and Van Cortlandt Lake. The closest main road is Broadway to the west. You can easily get there by subway, as the New York City Subway's Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street station is right outside the park on Broadway.

The area where the house stands used to be a marshy wetland next to Tibbetts Brook. In the 1690s, Van Cortlandt Lake was created along the brook. When the house was built in 1748, it was on a hillside. This hill was on the east bank of the Hudson River. The house and the land around it are now part of Van Cortlandt Park. The open fields around the mansion were created later, in the late 1800s. From the house, you could see the Spuyten Duyvil valley to the south. You could also see the Palisades to the west and Tibbetts Brook to the east.

Originally, there was a stone driveway leading to the house. This allowed people inside to hear visitors arriving. The entrance had gateposts that once had wooden bird sculptures on top. These sculptures were later moved inside the house. There were also horse chestnut trees on both sides of the gateposts. The gardens around the house were designed in a "Dutch manner." This included man-made terraces, large box trees, and water features like fountains. Big, old trees also surrounded the mansion. In the early 1900s, a Dutch garden was built south of the mansion. It had a canal, a fountain, and four square sections. This garden has since been replaced with trees and a herb garden.

History of the Mansion

Before Europeans arrived, the Lenape Native Americans lived on the land where the Van Cortlandt Mansion now stands. There was a Native American village nearby called Keskeskick. Adriaen van der Donck, a Dutch settler, was the first European to own this land. He bought it from the Dutch West India Company in 1646. After the British took over New Netherland in 1664, the land went to Elias Doughty. He sold a large part of it, including the house's site, to Frederick Philipse, Thomas Delavall, and Thomas Lewis. Philipse eventually bought out the others, making the land part of his large estate, Philipsburg Manor. Philipse's daughter, Eva, later married Jacobus Van Cortlandt. Jacobus was the son of Oloff Stevense Van Cortlandt, a Dutch brewer.

Jacobus Van Cortlandt bought more land from Philipse until 1699. He also built a dam on Tibbetts Brook to create Van Cortlandt Lake. Jacobus and his wife mostly lived in Manhattan. But they used the estate as a large farm, or plantation, in the early 1700s. It was easy to ship grain and timber from the property by water. This was because Tibbetts Brook connected to the Harlem River and Spuyten Duyvil Creek. In 1732, Jacobus bought even more land. In 1739, the estate went to Jacobus's son, Frederick Van Cortlandt. At that time, the land was considered part of lower Yonkers in Westchester County. The farm had many animals like horses, cattle, and sheep. They also grew crops like flax and various fruits. Several enslaved people worked on the plantation.

The House as a Home

The Van Cortlandt House is the oldest house still standing in what is now the Bronx. It's also one of only two old manor houses left in the Bronx, along with the Bartow–Pell Mansion.

Building the House (1740s-1770s)

Frederick Van Cortlandt started building the Van Cortlandt House in 1748. The Van Cortlandt House Museum says Frederick probably didn't build it himself. His family lived in another house nearby while the new one was being built. The mansion was built in a valley about a mile north of Kings Bridge, near what is now Broadway. Some believe it was built on or near the site of an even older farmhouse. East of the mansion were a mill, a small mill, and the Van Cortlandts' previous home. Woodlands were to the northeast. In his will, signed in October 1749, Frederick said the house was almost finished.

Frederick died before the house was completed. He left the estate to his son, Jacobus (James) Van Cortlandt. He also left 11 or 12 enslaved people who worked on the farm. The Van Cortlandt family burial ground, Vault Hill, was created in 1749. Frederick was buried there. After it was finished, the house was often called the "manor house." However, the true "manor" was the Van Cortlandt Manor in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. The mansion was also called "Lower Cortlandt's" to avoid confusion with another family farm.

The family used the grist mill and saw mill near the lake. Inside the house, they prepared and stored food like pork, beef, and fruits from the farm. The Van Cortlandts didn't live in this house all the time. They spent most of their time in Manhattan. The family often invited important people to the mansion. They served food like lobsters from the Long Island Sound and hams from their farm. Enslaved people did much of the work around the house, including laundry, cleaning, and cooking.

The Revolutionary War (1775-1783)

The Van Cortlandt family's land became a neutral zone during the American Revolutionary War. Both the British Loyalists and the American Patriots used it. In May 1775, James Van Cortlandt was asked to help decide if a fort should be built near his house. James tried to stay neutral, not fully supporting either side. Augustus Van Cortlandt, another family member, hid important city records under Vault Hill during the war. He returned them to the new American government later. Some family members stayed at the mansion for most of the war.

American Patriot leaders like Comte de Rochambeau, Marquis de Lafayette, and George Washington used the grounds. The house itself was one of Washington's headquarters. He stayed there after his troops lost the 1776 Battle of Long Island. Washington also stayed at the house before the Battle of White Plains. After that battle, British General William Howe made the house his headquarters in November 1776. Hessian troops had already looted the mansion before Howe arrived. British Admiral Robert Digby sometimes brought the future British King William IV to the mansion. Digby gave Augustus Van Cortlandt wooden bird sculptures taken from a Spanish ship. American troops tried to take back the house in 1777 but failed. A British captain named Rowe died in the house in 1780 after being wounded nearby. This led to stories that his ghost haunted the house.

James Van Cortlandt moved away during the war due to poor health and died in 1781. Since he had no children, his younger brother, Augustus Van Cortlandt, took over the property. Washington returned to the house in 1781 to plan with Rochambeau. Their troops waited outside on what is now the Parade Ground. Washington wanted to scout British forts in Upper Manhattan. But his troops instead went south to Virginia, where they defeated the British. Washington lit campfires outside the house to trick the British into thinking his troops were still there. Washington used the house one last time in 1783 after the Treaty of Paris. The British had just left Manhattan. Washington and George Clinton stopped at the house before entering the island.

After the War (Late 1700s-1800s)

Augustus Van Cortlandt's family moved into the house after the Revolution. Records from 1790 show that Augustus Van Cortlandt had 17 enslaved people on the property. By 1800, Augustus, his wife, another woman, and 10 enslaved people lived there. The 1810 census showed six free people and 15 enslaved people. The farm may have still been run as a plantation. Augustus Van Cortlandt owned the house until he died in 1823. He had no sons, so his son-in-law, Henry White, received the right to live there. Henry's son, Augustus White, could have the house if he changed his last name to Van Cortlandt.

Augustus White Van Cortlandt moved the mill on the estate to the lake shore in 1823. The enslaved people on the estate were freed in 1827. This was when slavery in New York became illegal. The younger Augustus owned the house until he died in 1839. He left the house to his brother, Henry White Van Cortlandt. Henry had no children and died later that year. Since neither brother had sons, the house went to their sister's son, Augustus Bibby Van Cortlandt. Augustus Bibby owned the house for 45 years. He updated the mansion and farmed much of the land. Fireplaces were changed to make room for stoves. In the late 1840s, the house had a front garden with box trees and fountains. The old mill and the Van Cortlandts' first house were still on the estate. The house's inside was decorated with many portraits.

New York City took over the southern part of Westchester County in 1874. The Van Cortlandt estate then became part of the Bronx. The Van Cortlandts wanted to sell their land by the 1870s. This was because the area was becoming more urban. In 1884, New York governor Grover Cleveland signed a law to create parks in the Bronx. This included what would become Van Cortlandt Park. The law allowed the city to buy 700 acres from Augustus Bibby. There were legal arguments about this for years. The Van Cortlandt family didn't fully leave the house until 1888. The mill next to Van Cortlandt Lake was used until 1889. The family held events in the house as late as 1890. The New York Herald Tribune said the house and land had "symbolized the vast wealth" of the Van Cortlandt family for generations.

The House as a Museum

New York City bought part of the Van Cortlandt estate in December 1888. This land became Van Cortlandt Park. Other parts of the estate were sold later. Most of the grain fields became a large lawn called the "Parade Ground." The Van Cortlandt House was saved. Parts of the mansion were fixed and repainted in 1889. For several years, only the caretaker's family lived there. Military officers used the house once a year for park activities. Until 1896, the mansion was also a barracks for the New York State Police. They guarded the bison that lived in Van Cortlandt Park. The New York City Police Department and the New York National Guard also used the house. The bison stayed there until they moved to the Bronx Zoo.

Becoming a Museum (Late 1800s-Early 1900s)

In March 1893, a park commissioner suggested turning the mansion into a museum. It would display items from the Revolutionary War. The park commissioners spent money on painting and repairs. In 1894, the city's Park Board voted to add a sign honoring Washington to the mansion. In 1896, the Society of Colonial Dames of the State of New York asked to fix the mansion. They wanted to run it as a historic house museum. The New York State Legislature gave the society control of the mansion by May. The Park Board agreed to lease the mansion to the society in December 1896. The first lease was for 25 years. The society then started fixing up the house. The project cost between $4,000 and $5,000. They wanted to make the house look like it did originally.

The Colonial Dames took over the mansion on May 27, 1897. They opened it to the public that day. At the time, the Van Cortlandt Mansion was one of the few old homes saved on public land in New York City. It was also one of the first historic house museums in the city. The Van Cortlandt Mansion was one of the few mid-1700s buildings in New York City that still had its original wood details. The museum was open every day and was usually free. On Saturdays, they charged 25 cents to help pay for the house's upkeep.

A colonial garden around the house was approved in May 1897. Samuel Parsons Jr., the park superintendent, started building it in August. The city also gave $15,000 for the garden. The Colonial Dames put up a tablet outside the mansion in late 1900. It told the house's history. By then, over 50,000 people had visited the museum. The next year, the old mill used by the Van Cortlandt family was destroyed by lightning. A statue of Major-General Josiah Porter was put up behind the house in 1902. The colonial garden next to the mansion was finished in 1903. A window from the old Rhinelander Sugar House was brought to the Bronx in 1903. It was put next to the mansion. By 1908, the mansion was easy to reach by subway.

Mid-1900s to Today

In the early 1910s, the Colonial Dames started raising money for more museum items. They also planned to build an addition to the house. But the Park Board's architect stopped these plans in 1912. The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks) asked for bids to build the addition in 1913. They first rejected all of them. After a new contract was approved, the addition was finished in 1916 or 1917. This addition was a caretaker's apartment next to the main house. NYC Parks also approved a contract for house repairs in late 1914. Architect Norman Isham was hired to renovate the mansion. This included fixing fireplaces, adding wood panels, and installing window shutters. By the late 1910s, the museum charged admission on Thursdays. It was free on Sundays but had shorter hours.

By the early 1930s, the Van Cortlandt House had 50,000 to 60,000 visitors each year. Many were from other countries. A walnut tree was planted in front of the mansion in 1938. It replaced an older tree where Washington had once stood. The guns outside the house were removed in 1942. Parks Commissioner Robert Moses said they were not historically important. The New York Herald Tribune reported in the mid-1940s that 100,000 people visited the Van Cortlandt House each year. In 1953, NYC Parks planned to put an iron fence around the mansion. This fence came from Delancey Street in Manhattan. In the late 1950s, a group found the building was still in good shape.

The Colonial Dames closed the Van Cortlandt House in December 1960 for renovations. They wanted to make it look more like an 18th-century home. The house was supposed to reopen in four months but was delayed until June 1961. This renovation fixed the walls and original floors. It also updated the caretaker's apartment and building systems. The house was open seven days a week in the 1960s, charging admission four days a week. By the 1970s, it was only open on weekends. It had several caretakers during this time. By the mid-1970s, the Bronx County Historical Society also helped maintain the house. But the Colonial Dames still ran it and provided decorations.

The house's grounds were landscaped in 1980. The house itself closed in 1986 for another renovation. This work included a new 150-seat auditorium under the house. It also expanded the cellar, added new bathrooms, and improved safety systems. The living rooms were repainted in their original colors. The renovation cost $571,900. It reopened in December 1988 to celebrate Van Cortlandt Park's 100th anniversary. The Van Cortlandt Mansion was one of the first members of the Historic House Trust, started in 1989. At that time, the house's roof needed to be replaced. By the early 1990s, the house was open five days a week and always charged admission. Students from Brooklyn College dug around the house between 1990 and 1992. Later, tennis courts were planned east of the mansion. Some worried this would block views and destroy old items. The courts were approved anyway.

By the mid-1990s, some rooms had peeling paint or water damage. There were also concerns about bugs in the furniture. The museum's director wanted to renovate the house for $1 million. The roof was to be fixed with $250,000 from the city. But there wasn't enough money for other repairs. The museum only had a $100,000 yearly budget. The director also lived in the house as its caretaker. The Colonial Dames still run the Van Cortlandt House Museum today.

Students from Brooklyn College did more digging at the site in 2003. The house was open six days a week in the 2000s. The house's dining room was restored in 2015. This work fixed the wood panels, wallpaper, and fireplace tiles. The mansion closed in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. It reopened in 2021 for self-guided tours. The house's communication systems were updated in 2022. The fence around the house is planned to be rebuilt soon.

How the House Looks (Architecture)

The house was designed by someone whose name we don't know. It's built in the Georgian style and is two and a half stories tall. People say it was based on Philipse Manor in Westchester County. The house has an L-shape, with parts extending to the south and east. The southern part was probably built first, then the eastern part. A lean-to was added in the 1800s. A caretaker's apartment, next to the main house, was added before World War I.

Outside the House

The house is made of carefully cut fieldstone. Older descriptions from the late 1800s say it has a rubblestone front. One corner of the house has a special stone with the year 1748 carved into it. The first floor is raised, so there are several entrances with wooden porches. Each porch has a small set of steps with railings. The original doors were later replaced with Dutch-style doors. The outside of the house doesn't have many fancy decorations. But one family member said the design showed the "substantial comfort" of the time. Next to the L-shaped main house is the caretaker's apartment. It also has stone walls and brick window frames. The caretaker's apartment is on the north side, making the whole building look like a C-shape.

The windows have brick frames and sash windows with many small glass panes. The original windows were clear. But by the late 1800s, they looked like ground glass. The windowsills are part of the outer walls. The sills on the second floor are a bit different from those on the first floor. Above the windows are special brick keystones. These keystones have carvings of funny or strange faces, called grotesque masks. Each mask has a different face, representing a different Van Cortlandt. A local historian said the best bricks were placed facing outward. The National Park Service says the Van Cortlandt House was the only building in the area with these grotesque masks.

At the top of the house is a cornice that supports a sticking-out soffit. The underside of the soffit has decorative blocks called modillions. The main house has a mansard roof made of slate. There are no railings or decks on the roof. Seven dormer windows stick out from the roof: three facing east, one west, and three south. Each dormer has a window and a triangular shape above it. The house had several brick chimneys, like other large homes in the Hudson Valley. Not many houses had multiple chimneys back then. But this design allowed heat to reach most rooms.

Inside the House

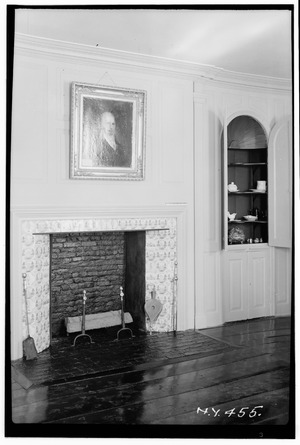

The inside of the house generally follows a Georgian style. Most rooms had fireplaces on their north walls and windows on at least one other wall. There's lots of detailed wood carving throughout the house. Several fireplaces have Dutch tiles.

Unlike city mansions, but common for country estates, the main entertaining rooms were on the first floor. The back of the house had a service area. Servants could move around without guests seeing them. The first floor's southern part had an entrance hall with two living rooms on either side. The eastern part had a side hall and dining room. The second floor is simpler than the first. It's also L-shaped. The caretaker's apartment has seven rooms, including a kitchen and two bathrooms.

Basement

The kitchen is in the raised basement. The basement walls are 3 feet thick, which was a way to protect the house. They are made of plaster over stone. There are two small windows high on the western wall. These might have been for defense. The basement ceiling has low wooden beams. These beams are 11 by 13 inches and were hand-carved from cypress and cedar. Water for the kitchen originally came from Vault Hill. There's a Dutch brick oven built into the kitchen wall. One wall has a wide, short fireplace with an arched opening. A dresser and a closet for dishes were in the kitchen. There's also a newer basement area with a classroom and an auditorium. The museum's restrooms are also in the basement.

First Floor

You enter the front hall from the main entrance on the south side. Doorways with fancy frames lead to living rooms on the west and east. The front hall floor is made of yellow pine boards covered with a painted canvas cloth. The western wall of the front hall has a U-shaped staircase. This staircase goes up to the second and third floors. The inside of the staircase has a railing with turned posts. There's a round post at the bottom and square posts on each landing. The outer wall of the staircase has wood panels. At the first landing, there's a special spot with a large window. The staircase's high ceiling showed how wealthy the family was when the house was built. Behind the front hall is the rear hall. It has a simple staircase and leads to the dining room and a servants' entrance. The rear hall was added after Frederick Van Cortlandt died. It gave his widow a private entrance.

To the left (west) of the front hall is the western living room. This room was used by Washington in 1783. On the northern wall is a fireplace with blue-and-white tiles. These tiles show scenes from the Bible. Columns separate the fireplace from an arched cupboard on each side. Each cupboard has two doors and shelves for dishes. The rest of the north wall is painted blue and has wood panels. The other three walls are white plaster with a baseboard, a dado rail, and a decorative molding at the ceiling. The south wall has three windows. There were seats next to the window on the south wall.

To the right (east) of the front hall is the eastern living room. This room was meant for formal gatherings, like tea parties or card games. Each wall is covered in wood panels with a cornice at the top. This room has a fireplace that was probably added after the house was finished. The fireplace has a marble hearth and a carved marble mantel. It has a shelf and a carved design underneath. Above the fireplace is an overmantel with more carvings. It shows Adam and Eve, a serpent, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

The dining room is in the eastern part of the house. It's separated from the eastern living room by the rear hall. It's designed in a late 1700s style. It probably wasn't used for meals originally. Americans usually didn't have special dining rooms before the American Revolution. The dining room had a fireplace with a mantel from around 1800. It had decorations like columns and fan shapes. A small closet was built into the side of the fireplace mantel. It was used to keep items warm in winter. One corner of the room also had a large white cupboard for dishes. The walls are light plaster above dark buff wood panels. A chimney is on the north wall. The ceiling molding and fireplace mantel were restored later.

Upper Floors

On the second floor, there's a hallway in the middle of the southern part. It connects to the house's main staircase. At the south end of the hallway is a window with shutters and a seating area.

Next to the hallway are two rooms, one to the west and one to the east. These are bedrooms. Both have white walls, doorways with molded frames, and fireplaces with wood panels and white tiles. They also have windows with inside shutters and decorative moldings. The western room was called the Washington bedroom. It had furniture used by Washington. The north wall of this bedroom has a fireplace with closets on either side. Behind the eastern bedroom was a spinning room. A third bedroom to the northeast has a fireplace with Dutch tiles showing stories. One bedroom was named the Monroe room because a family maid married a man named Monroe.

A narrow U-shaped staircase in the second-floor hall goes up to the third floor. On the third floor were two smaller rooms for servants. One of these rooms was not finished. The attic has been turned into an exhibit. It tells the story of the enslaved people who worked on the Van Cortlandt plantation.

How the Museum Works

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation owns the Van Cortlandt House. The National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York still runs the mansion as a museum.

What's in the Collection?

When the house first opened as a museum, the western living room was a special museum area. The other rooms showed items from the Colonial Dames and their friends. In the early years, one room had items from the colonial and Revolutionary War times. Old cooking tools were shown in the kitchen. The western living room had Benjamin Franklin's fireplace tools and maps from as early as 1642. In the eastern living room, there was furniture like chairs, a writing desk, and candle stands. The dining room displayed dishes and a dinner table. The western bedroom on the second floor had furniture from Washington's time, like his bed and a clock. The eastern bedroom had a chest and a printing press. The spinning room had tools for needlework. Other items included wooden bird sculptures and two cannons outside.

In the 1900s, more items were added to the collection. These included handmade liquor bottles found in 1902. In the 1910s and 1920s, the house had many colonial and Dutch furniture pieces. One living room had a fancy mirror and a secretarial desk. The upstairs rooms kept their old four-poster beds with tapestries. The house displayed items of all sizes, plus china and furniture. On the third floor, there was a nursery with children's items like a bed and tea dishes.

By the 1970s, the western living room had a snuff box from Peter Stuyvesant and pistols from Aaron Burr. The eastern living room had a cello and a spinet. The dining room had plates set for a meal. The kitchen had various tools, a powder horn, and a rifle. The house also had a Dutch storage chest, several poster beds, and a dollhouse. The mansion still has much of its old furniture today. This includes cupboards, cradles, and built-in cabinets. The museum also shows colorful rugs, bedspreads, and utensils. In the modern dining room, there's a set of drawers, six chairs, and a table.

Events and Programs

After the museum opened, it started having monthly "antique exhibits" in 1903. Early exhibits included old pewter, small portraits, and needlework pictures. In the 1920s, the museum showed colonial documents, paintings, and books. In the 1950s, it displayed glass, silverware, china, and pottery from the 1600s and 1700s. The Colonial Dames have also put on live performances to raise money for the house. For example, they staged a play in 1960. By the 1970s, the house hosted St. Nicholas Day shows, concerts, and Revolutionary-era military demonstrations. In the late 1900s, the house continued to have concerts, carols, children's programs, and history talks.

Today, the museum hosts events like historical reenactments. The museum offers tours all year, both self-guided and led by guides. The house also hosts special events.

What People Think of the House

Reviews and Media

In 1889, a reporter called the building "solid, substantial, massive." They said it was kept "in splendid condition." After it became a museum, The New York Times said it was "one of the most interesting relics of the Colonial period." The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote that "The house alone...is worth a visit." A writer for Town and Country said in 1901 that the house kept "all the glory of that interesting era." Another Times article in 1911 said the house was a reason to visit Van Cortlandt Park. A writer for The Christian Science Monitor wrote in 1915 that "this house helps us to picture their days of generous means and dignified living." However, a writer for The American Architect said in 1919 that the house showed too many items that weren't related to its history.

One critic in 1927 said the Van Cortlandt House was one of the few old houses in New York City that still looked grand. Another writer in 1964 said the house had "interior paneling and furnishings of the first rank." A reporter in 1984 called it the Bronx's "most prestigious house." Bronx historian Lloyd Ultan said in 1995 that the house was "highly significant to the history of the nation." This was because of its use during the American Revolutionary War. Times critic Mimi Sheraton wrote in 2001 that the house's "almost rustic Georgian simplicity" was different from the grander Bartow–Pell Mansion.

The house has appeared in various media. Its historical importance was recognized early on. In 1914, the New York City Art Commission took pictures of the mansion. The Van Cortlandt House was also shown in a mural painted in the Bronx County Courthouse in 1934. A picture of the house was displayed at the City Gallery in 1981. The mansion was even used as a stand-in for an Irish house in an episode of the TV series Boardwalk Empire.

Protected Status

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) named the Van Cortlandt House a city landmark in March 1966. The city's Board of Estimate approved this in August. This made the mansion one of the first homes in the Bronx to be a city landmark. The mansion was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1967. It became a National Historic Landmark in 1976. The LPC also named the inside of the Van Cortlandt Mansion a city landmark in July 1975. This protected several Georgian-style rooms.

See also