William Walker (filibuster) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Walker

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| President of Nicaragua (Unrecognized) |

|

| In office July 12, 1856 – May 1, 1857 |

|

| Preceded by | Patricio Rivas |

| Succeeded by | Máximo Jerez and Tomás Martínez |

| President of Sonora (Unrecognized) |

|

| In office January 21, 1854 – May 8, 1854 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| President of Baja California (Unrecognized) |

|

| In office November 3, 1853 – January 21, 1854 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 8, 1824 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | September 12, 1860 (aged 36) Trujillo, Colón, Honduras |

| Cause of death | Firing squad |

| Resting place | Old Trujillo Cemetery, Trujillo, Colón, Honduras |

| Political party | Democratic (Nicaragua) |

| Alma mater |

|

| Signature | |

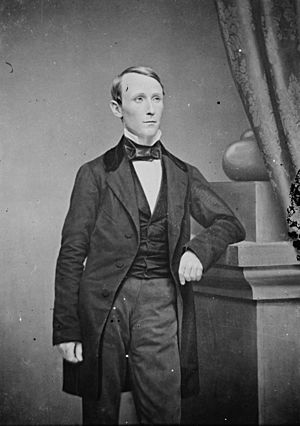

William Walker (May 8, 1824 – September 12, 1860) was an American doctor, lawyer, journalist, and mercenary. During a time when the United States was growing, Walker led private military trips. He wanted to create his own colonies in Mexico and Central America. These types of adventures were known as "filibustering".

After moving to California, Walker tried to take over Baja California and Sonora in 1853–1854. He announced these areas were an independent "Republic of Sonora". However, Mexican forces quickly pushed him back to California.

Later, in 1855, Walker went to Nicaragua. He led a group of paid soldiers for the Democratic Party during their civil war. He gained control of the Nicaraguan government and, in July 1856, made himself the country's president.

The U.S. President Franklin Pierce recognized Walker's government in Nicaragua. At first, some people in Nicaragua supported him. But Walker upset a powerful businessman named Cornelius Vanderbilt. Walker took control of Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company, which was important for travel between New York City and San Francisco. The British Empire also saw Walker as a threat to their plans for a Nicaragua Canal. As ruler, Walker brought back slavery and threatened nearby Central American countries. A group of armies, led by Costa Rica, defeated Walker. He was forced to leave the presidency of Nicaragua on May 1, 1857.

Walker tried to restart his plans. In 1860, he wrote a book called The War in Nicaragua. In it, he linked his efforts to conquer Central America with the idea of spreading slavery. He hoped to get support from people in the Southern United States before the American Civil War. That same year, Walker went back to Central America. But the Royal Navy arrested him and gave him to the Honduran government. They executed him.

Contents

William Walker's Life Story

William Walker was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824. His father was an English settler, and his mother's father was an officer in the American Revolutionary War. One of his uncles was John Norvell, a U.S. Senator. Walker was engaged to Ellen Martin, but she passed away from yellow fever before they could marry. He never had children.

Walker was very smart. He graduated from the University of Nashville at age 14. By 19, he earned a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He continued his medical studies in Edinburgh and Heidelberg. He worked briefly as a doctor in Philadelphia.

He then moved to New Orleans and studied law. After a short time as a lawyer, he became an editor for a newspaper. In 1849, he moved to San Francisco and worked for the San Francisco Herald. He was involved in three duels there.

Walker then started thinking about taking over large parts of Central America. He wanted to create new slave states that could join the U.S. These military campaigns were called filibustering. They were supported by a secret group called the Knights of the Golden Circle.

A Duel in California

Walker became well-known after a duel on January 12, 1851. He had criticized a man named William Hicks Graham in his newspaper. Graham challenged Walker to a duel. They met at Mission Dolores. Each man had a Colt Dragoon pistol with five shots. They stood ten paces apart. Graham fired two shots, hitting Walker in his leg. Walker tried to shoot but missed. The duel ended when Walker gave up. Graham was arrested but soon released. This event was reported in The Daily Alta California.

His Time in Mexico

In 1853, Walker went to Guaymas, Mexico. He wanted the Mexican government to let him start a colony there. He said his colony would protect the U.S. from Indian raids. Mexico said no.

Walker returned to San Francisco, determined to get his colony anyway. He began to gather American supporters of slavery and the idea of Manifest Destiny. Most of these supporters were from Tennessee and Kentucky. Walker's plans grew. He no longer just wanted a colony; he wanted to create an independent Republic of Sonora. He hoped it would eventually join the U.S., like the Republic of Texas had. He raised money by selling promises of land in Sonora.

On October 15, 1853, Walker set off with 45 men to conquer the Mexican territories of Baja California Territory and Sonora State. He captured La Paz, the capital of Baja California. On November 3, 1853, he declared it the capital of a new "Republic of Lower California" and made himself president. He then made slavery legal in the region, using laws from the U.S. state of Louisiana.

Walker moved his headquarters twice to stay safe from Mexican attacks. He moved to Cabo San Lucas and then to Ensenada. Although he never fully controlled Sonora, he declared Baja California part of a larger Republic of Sonora. But he lacked supplies, and the Mexican government fought back strongly. Walker was soon forced to leave.

Back in California, Walker was accused of starting an illegal war. However, many people in the southern and western U.S. supported his filibustering ideas because of Manifest Destiny. Walker was tried in court but was found not guilty by a jury after only eight minutes.

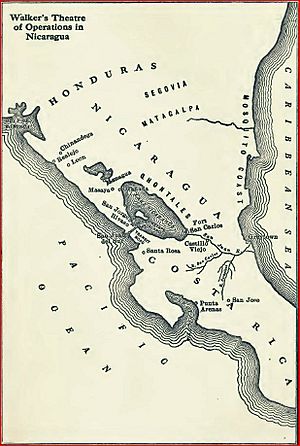

Taking Over Nicaragua

At this time, there was no easy way to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The transcontinental railway in the U.S. did not exist yet. So, a major trade route between New York City and San Francisco went through southern Nicaragua. Ships from New York sailed up the San Juan River and across Lake Nicaragua. Then, people and goods traveled by stagecoach across a small piece of land near Rivas to reach the Pacific Ocean and ships to San Francisco. A company owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt, the Accessory Transit Company, managed this route.

In 1854, a civil war started in Nicaragua. The Legitimist Party (Conservatives) fought against the Democratic Party (Liberals). The Democratic Party asked Walker for military help. To get around U.S. laws about staying neutral, Walker signed a contract with the Democratic president, Francisco Castellón. The contract allowed Walker to bring up to 300 "colonists" to Nicaragua. These "colonists" were actually mercenaries who could carry weapons and fight for the Democratic government.

Walker left San Francisco on May 3, 1855, with about 60 men. Once they landed, 110 local people joined them. Famous explorer and journalist Charles Wilkins Webber was with Walker's group. So was Charles Frederick Henningsen, a Belgian adventurer who had fought in many wars.

With President Castellón's permission, Walker attacked the Legitimists in Rivas. He was pushed back but caused many losses for the enemy. In this battle, a school teacher named Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio bravely burned down the Filibuster headquarters. On September 3, Walker defeated the Legitimist army in the Battle of La Virgen. On October 13, he captured Granada, taking control of the country.

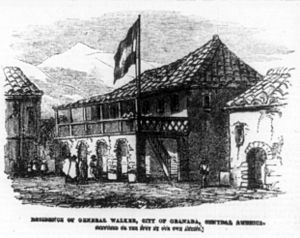

At first, Walker ruled Nicaragua through a temporary president, Patricio Rivas. U.S. President Franklin Pierce recognized Walker's government on May 20, 1856. On September 22, Walker brought back laws that allowed slavery in Nicaragua. He hoped this would gain him support from the Southern U.S. states.

Facing Challenges in Nicaragua

Walker's actions worried neighboring countries and investors. They feared he would try to conquer more of Central America. Two of Vanderbilt's employees, C. K. Garrison and Charles Morgan, helped Walker financially. In return, Walker, as ruler of Nicaragua, took control of Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company. Vanderbilt was furious and sent agents to the Costa Rican government to help them fight Walker.

The President of Costa Rica, Juan Rafael Mora Porras, was concerned about Walker. He began preparing his country's army. Walker sent a group of 240 men to invade Costa Rica. But this force was defeated at the Battle of Santa Rosa on March 20, 1856.

A major defeat for Walker happened during the Campaign of 1856–57. The Costa Rican army, led by President Porras and his generals, defeated Walker's forces in Rivas on April 11, 1856. This was the Second Battle of Rivas. In this battle, a soldier and drummer named Juan Santamaría became a hero. He sacrificed himself by setting the Filibuster stronghold on fire. Walker then deliberately poisoned the water wells in Rivas with dead bodies. This caused a cholera epidemic that killed nearly 10,000 civilians in Costa Rica.

From the north, Honduran and Salvadoran troops joined the fight against Walker. Florencio Xatruch led these troops. Later, José Joaquín Mora Porras became the leader of all the Central American armies.

After Walker surrendered, Xatruch made a grand entrance into Comayagua, the capital of Honduras. Hondurans today are sometimes called "Catracho" because of Xatruch and his successful campaign. This nickname came from Nicaraguans trying to pronounce Xatruch's name.

The Costa Rican Army played a key role in uniting the Central American armies. They fought battles along the San Juan River. By controlling this river, Costa Rica stopped more soldiers from reaching Walker by sea. Costa Rica also used the conflict between Vanderbilt and Walker to get the U.S. to stop supporting Walker.

Walker lived in Granada and made himself President of Nicaragua after an election that was not fair. He started his rule on July 12, 1856. He began an "Americanization" program. He brought back slavery, made English an official language, and changed money rules to encourage Americans to move there. He tried to get support from the Southern U.S. by saying his fight was about spreading slavery. This made him popular with Southern whites.

However, Walker's army became weaker because many soldiers left and a cholera sickness spread. The Central American armies, led by Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras, finally defeated him.

On October 12, 1856, a Guatemalan officer named José Víctor Zavala bravely ran through heavy gunfire to capture Walker's flag. He brought it back to his army, shouting that the Filibuster bullets could not kill him.

On December 14, 1856, Granada was surrounded by 4,000 soldiers from Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. One of Walker's generals, Charles Frederick Henningsen, ordered his men to burn the city before escaping. They spent over two weeks destroying Granada. All that was left were ruins with the words "Aqui Fue Granada" ("Here was Granada").

On May 1, 1857, Walker gave up to the U.S. Navy. He was sent back to the U.S. In New York City, he was welcomed as a hero. But he upset people when he blamed the U.S. Navy for his defeat. Six months later, he tried another expedition. But the U.S. Navy arrested him again and sent him back to the U.S.

His End and Legacy

After writing a book about his Central American adventures, Walker returned to the region. British settlers on Roatán, Bay Islands, asked him for help. They feared the Honduran government would take control of their islands. Walker landed in Trujillo, but a British naval officer, Nowell Salmon, arrested him. The British had interests in the area and saw Walker as a threat.

Instead of sending him back to the U.S., Salmon handed Walker over to the Honduran government. Walker was sentenced to death. He was executed by a firing squad on September 12, 1860. William Walker was 36 years old. He is buried in the Old Trujillo Cemetery in Honduras.

How He Is Remembered

William Walker convinced many people in the Southern U.S. that it was a good idea to create an empire of slave-holding states in Latin America. Before the American Civil War ended, Walker was very popular in the southern and western U.S. He was known as "General Walker" and the "gray-eyed man of destiny." However, people in the Northern U.S. often saw him as a pirate.

In Central American countries, the successful fight against William Walker in 1856–1857 is a source of great national pride. It is celebrated as a key moment in their history. April 11 is a national holiday in Costa Rica, remembering Walker's defeat at Rivas. Juan Santamaría, who was a hero in that battle, is one of Costa Rica's national heroes. The main airport in San José is named after him.

Even today, the idea of Central American countries working together against Walker is remembered. It is a shared history that unites the "catracho" nations of Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, along with their Nicaraguan allies.

Works

- Walker, William. The War in Nicaragua. New York (NY): S.H. Goetzel, 1860.

See also

In Spanish: William Walker para niños

In Spanish: William Walker para niños

- Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon

- Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret society interested in annexing territories in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to be added to the United States as slave states

- Nicaragua Canal

- Panama Canal

- Florencio Xatruch

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |