First transcontinental railroad facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First transcontinental railroad |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Overview | |

| Other name(s) | Pacific Railroad |

| Owner | U.S. Government |

| Locale | United States of America |

| Termini | Council Bluffs, Iowa (Omaha, Nebraska) Alameda Terminal, starting September 6, 1869; Oakland Long Wharf, starting November 8, 1869 (San Francisco Bay) |

| Service | |

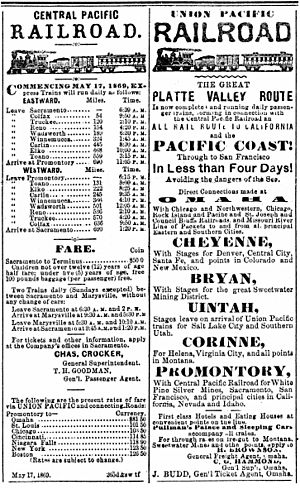

| Operator(s) | Central Pacific Union Pacific |

| History | |

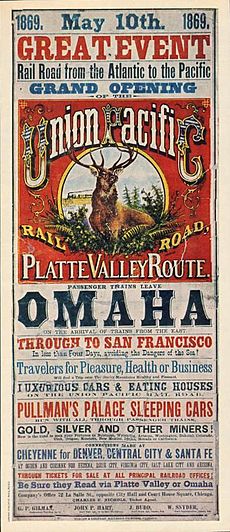

| Opened | May 10, 1869 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 1,912 mi (3,077 km) |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

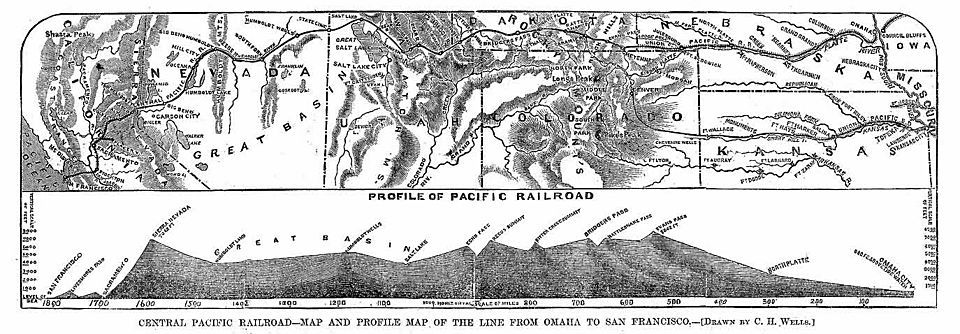

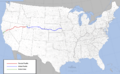

The first transcontinental railroad in North America was a continuous railway line. It was built between 1863 and 1869. This amazing project connected the existing eastern U.S. rail network in Council Bluffs, Iowa, to the Pacific coast. The western end was at the Oakland Long Wharf on San Francisco Bay.

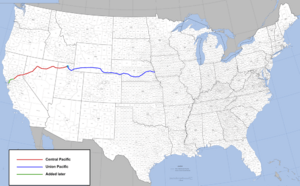

Three private companies built this railroad on public lands. They received large land grants from the U.S. government. Both state and U.S. government bonds helped pay for the construction. The Western Pacific Railroad Company built 132 miles (212 km) of track. This went from Alameda/Oakland to Sacramento, California. The Central Pacific Railroad Company of California (CPRR) built 690 miles (1,110 km) east. Their section went from Sacramento to Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. The Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) built 1,085 miles (1,746 km) westward. This part started from Council Bluffs, Iowa and Omaha, Nebraska and went to Promontory Summit.

The railroad officially opened on May 10, 1869. This was when CPRR President Leland Stanford hammered the golden "Last Spike" at Promontory Summit. The final section from Sacramento to San Francisco Bay was finished within six months. This new coast-to-coast connection changed the American West. It made travel and shipping goods much faster, safer, and cheaper.

The first passengers arrived at the Alameda Terminal on September 6, 1869. They then took a steamer across the bay to San Francisco. Two months later, the rail end moved to the Oakland Long Wharf. This new station opened on November 8, 1869. Ferries continued to connect San Francisco with the Oakland Pier.

The CPRR later bought 53 miles (85 km) of track from the UPRR. This section went from Promontory Summit to Ogden, Utah Territory. Ogden became the main meeting point for trains from both companies. The transcontinental line became known as the Overland Route. This was the name of the main passenger service that used the line until 1962.

Contents

Building the Transcontinental Railroad

Early Ideas for a Railroad

People started thinking about a railroad connecting the East and West coasts early on. One of the first to suggest it was Hartwell Carver in 1847. He asked the U.S. Congress for support to build a railroad from Lake Michigan to the Pacific Ocean.

Exploring Possible Routes

Congress liked the idea and decided to explore it. From 1853 to 1855, the Department of War led expeditions. These "Pacific Railroad Surveys" explored the American West to find the best routes. Reports from these trips described different paths. They also included lots of information about the American West.

The surveys helped decide that a southern route would need land south of the Gila River. This led to the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. In 1856, a House of Representatives committee said a railroad was a "necessity." They believed it was needed to connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

Choosing the Best Route

The U.S. Congress had strong disagreements about where the railroad should start. They considered three main routes:

- A northern route through Montana to Oregon Territory. This was hard due to rough land and heavy snow.

- A central route along the Platte River in Nebraska. It would go through South Pass in Wyoming. Snow was still a worry on this path.

- A southern route across Texas, New Mexico Territory, and the Sonora desert. This would connect to Los Angeles, California.

The central route was chosen. Then, the western end was set as Sacramento. But the eastern end was still debated. Three places along the Missouri River were considered:

- St. Joseph, Missouri.

- Kansas City, Kansas / Leavenworth, Kansas.

- Council Bluffs, Iowa / Omaha, Nebraska.

Council Bluffs, Iowa had several benefits. It was away from the Civil War fighting in Missouri. It was the shortest way to South Pass. Also, it followed a fertile river valley that would attract settlers. Abraham Lincoln, who was president, chose Council Bluffs/Omaha.

Key People Behind the Railroad

Many important people helped make the transcontinental railroad happen.

Asa Whitney's Vision

Asa Whitney was a big supporter of the central route. He dreamed of a railroad from Chicago to northern California. He thought selling land along the route could pay for it. Whitney traveled a lot, printed maps, and presented his ideas to Congress. He even explored parts of the route himself.

Theodore Judah, the Engineer

Theodore Judah was a strong advocate for the central route. He worked hard to get the project approved. He also surveyed the difficult route through the Sierra Nevada mountains. In 1852, Judah was chief engineer for the first railroad west of the Mississippi River. He believed a railroad could cross the Sierra Nevada.

In 1856, Judah wrote a long proposal for a Pacific railroad. He shared it with important leaders in Washington D.C. In 1859, he became the official lobbyist for the Pacific Railroad Convention. He even met with President James Buchanan. Judah found a practical route over the Sierra Nevada mountains. He formed a group to raise money for the railroad. Sadly, Judah died in 1863 from yellow fever.

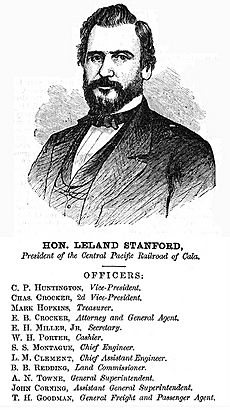

The Big Four Investors

Four businessmen from northern California formed the Central Pacific Railroad. They were:

- Leland Stanford, the President.

- Collis Potter Huntington, the Vice President.

- Mark Hopkins, the Treasurer.

- Charles Crocker, the Construction Supervisor.

These men became very rich from their involvement with the railroad. They were known as "The Big Four."

Thomas Durant and the Union Pacific

Dr. Thomas Clark "Doc" Durant was a key figure in the Union Pacific Railroad. He was the Vice President and controlled much of its financing. Unlike the Central Pacific, the Union Pacific's money matters were often controversial. Durant used clever ways to control the railroad's stock. He also made sure the Union Pacific built slowly at first. This was to increase his profits.

Getting Approval and Money

Laws to Build the Railroad

In 1860, a bill to fund the railroad was introduced in Congress. It passed the House but failed in the Senate. Southern states wanted a southern route, causing disagreements. After the southern states left the Union, the bill passed in 1862. President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 into law on July 1. This law created two companies: the Central Pacific Railroad in the west and the Union Pacific Railroad in the Midwest. They were to build the railroad from the Missouri River to San Francisco Bay. Another act in 1864 added more support. The 1863 act also set the standard gauge (width) for the tracks.

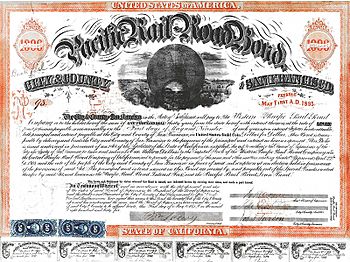

How the Government Paid

To pay for the project, the government issued 30-year bonds. The railroad companies were paid per mile of track laid. They got $16,000 per mile for flat land. This went up to $32,000 per mile for foothills and $48,000 per mile for mountains. The companies also sold their own bonds and stock.

Union Pacific's Money Matters

The Union Pacific had trouble selling its stock. Brigham Young, a leader of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was one of the few who bought stock. He also provided workers. Thomas Durant found ways to control about half of the railroad's stock. He also made money by building extra, unneeded track. This was because the railroad was paid by the mile.

Central Pacific's Money Matters

Collis Huntington, a merchant, heard Theodore Judah's plan. He convinced Judah to accept money from him and four others. These men were Mark Hopkins, James Bailey, Leland Stanford, and Charles Crocker. They invested $1,500 each and formed the Central Pacific Railroad. These "Big Four" investors eventually made millions.

After Judah's death, the Central Pacific's engineering was led by Samuel S. Montegue and Lewis M. Clement.

Land Grants for the Railroad

Congress gave the railroads a 200-foot (61 m) wide right-of-way corridor. They also got land for stations and yards. In addition, they received alternating sections of government land. This was 6,400 acres (2,590 ha) per mile for 10 miles (16 km) on both sides of the track. The railroads got odd-numbered sections, and the government kept even ones. This "checkerboard pattern" helped the companies raise money. They sold bonds based on the land's value. They also sold land to settlers, which helped the West grow quickly.

The total land given to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific was huge. It was larger than the state of Texas. If the companies didn't sell the land in three years, they had to sell it cheaply. If they didn't repay the bonds, the railroad would go to the U.S. government. To encourage people to move West, Congress passed the Homestead Acts. These acts gave 160 acres (65 ha) of land to people who would improve it.

How Companies Made Extra Money

The laws for the railroad didn't have enough rules. The companies used this to make extra profit. They knew the railroad itself wouldn't make money for a while. So, they decided to profit from the construction. Both groups of investors created separate companies to do the building. They controlled these new companies and paid them generously. The Central Pacific's company was called the "Contract and Finance Company." The Union Pacific's was called "Crédit Mobilier of America." This company later caused a big scandal.

The lack of oversight also made both companies build more track than needed. They were paid for each mile, so they kept building past each other.

Workers and Their Pay

Many engineers and surveyors for the Union Pacific had worked in the American Civil War. They had experience repairing and running railroads. Most of the workers for the Union Pacific were former soldiers. Many Irish immigrants also worked for them.

The Central Pacific Railroad also received federal money and bonds from California. They had trouble finding workers. Most white workers in California preferred mining or farming. The railroad tried hiring Chinese immigrants. Many were escaping poverty and war in China. These Chinese workers proved to be very good. The CPRR then hired as many as they could, even recruiting from China.

Chinese laborers did most of the hard manual work. They were responsible for digging and blasting. The railroad also hired some African Americans. Most white and black workers were paid $30 per month, plus food and lodging. Chinese workers initially got $31 per month and lodging. They preferred to cook their own meals. In 1867, their pay was raised to $35 per month after a strike. Chinese labor was very important to the Central Pacific's success.

Building the Transcontinental Route

Starting Construction

The Central Pacific began construction on January 8, 1863. Most of their tools and machinery came from the East Coast. They were shipped by boat around Cape Horn or across the Isthmus of Panama. The Panama route was faster but more expensive. Once in California, items were shipped up the Sacramento River to Sacramento. Many machines had to be put back together. Wood for ties and bridges came from California forests.

The Union Pacific Railroad started later, in July 1865. They had delays getting money and supplies because of the Civil War. Their starting point in Omaha, Nebraska was not yet connected by rail. Equipment arrived by paddle steamers on the Missouri River.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the Union Pacific still faced high prices for supplies. This was because other companies were also building or repairing railroads.

Railroad Standards

At that time, different railroads used different track widths. This made it hard to transfer cars. For the transcontinental railroad, they chose the standard gauge. This width is still used today.

The rails were mostly made of iron. Steel was available but not yet common for rails. The companies wanted to finish the project quickly and cheaply. Within a few years, most railroads switched to stronger steel rails.

Time and Telegraph

Time was not standard across the U.S. until 1883. Each railroad set its own time. To communicate, they built telegraph lines next to the tracks. These lines helped track trains and avoid accidents. They also replaced the older First transcontinental telegraph line.

Union Pacific's Path West

The Union Pacific's 1,087 miles (1,749 km) of track started in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Abraham Lincoln chose Omaha as the main transfer point. Trains initially crossed the Missouri River by ferry. A bridge was built later, in 1872.

The route climbed west from Omaha. It followed the north side of the Platte River valley through Nebraska. This path was similar to the Oregon Trail. By December 1865, the Union Pacific had only laid 40 miles (64 km) of track.

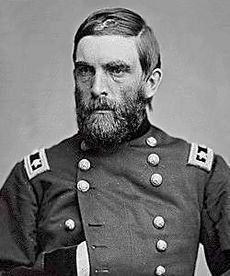

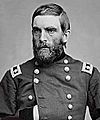

After the Civil War, construction sped up. Grenville M. Dodge became chief engineer. John "Jack" Casement was hired as the construction boss. He used special rail cars as portable bunkhouses for workers. Hunters provided buffalo meat for the crews.

Survey teams working ahead were sometimes attacked by Native Americans. The U.S. Army increased patrols to protect the workers. Temporary towns, called "Hell on wheels", followed the railroad's progress.

The Platte River valley allowed for fast track laying. They often laid a mile (1.6 km) or more of track a day in 1866. Building bridges was the main delay. They built a long bridge over the North Platte River. The town of North Platte, Nebraska was built there in December 1866.

A new, shorter route was found across Wyoming in 1867. This route went through Evans pass (also called Sherman's Pass). This pass was discovered by James Evans. It was located near where the towns of Cheyenne and Laramie would be built. This new path was 150 miles (240 km) shorter and had a flatter slope.

The Union Pacific reached Cheyenne in December 1867. They laid about 270 miles (430 km) that year. Cheyenne became a major railroad center. It connected to Denver in 1870. The railroad continued establishing towns like Fremont, Grand Island, and Rawlins.

The tracks reached Green River on October 1, 1868. This was the last big river to cross. On December 4, 1868, the Union Pacific reached Evanston.

In Utah Territory, the railroad went through the Wasatch Mountains. It followed the rugged Echo Canyon and Weber River canyon. To speed things up, thousands of Mormon workers were hired. They cut, filled, blasted, and tunneled through the canyons. The longest tunnel was 757 feet (231 m) long. They used nitroglycerine explosives, which were dangerous but fast.

The tracks reached Ogden, Utah, on March 8, 1869. From Ogden, the railroad went north of the Great Salt Lake. It passed through Brigham City and Corinne. Finally, it connected with the Central Pacific Railroad at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869.

Central Pacific's Path East

The Central Pacific laid 690 miles (1,110 km) of track. It started in Sacramento, California, in 1863. The route went over the rugged 7,000-foot (2,100 m) Sierra Nevada mountains at Donner Pass. The elevation change was huge, but Theodore Judah had found a route that was gradual enough.

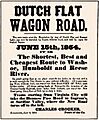

In 1864, the Central Pacific opened a toll road. This "Dutch Flat and Donner Lake Wagon Road" helped carry supplies for the railroad. It also carried freight to mining towns in Nevada. This helped pay for the railroad construction.

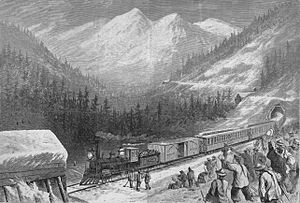

The Central Pacific had eleven tunnels to build through the Sierra Nevada. Seven of these were in a 2-mile (3.2 km) stretch near Donner Summit. Workers drilled holes by hand, filled them with black powder, and blasted the rock. The black powder came from a factory in California. The Central Pacific used a lot of it.

The Summit Tunnel (Tunnel Number 6) was 1,660 feet (506 m) long. Work started in late 1865. It was very slow, only about 1 foot (0.3 m) per day per side. To speed things up, they dug a 125-foot (38 m) vertical shaft in the middle. This allowed them to work on four tunnel faces at once. Progress got faster when they started using nitroglycerin.

Hills had to be cut through, and valleys filled. This was called "cut and fill" construction. Workers used shovels, picks, and carts. Blasting with black powder helped remove rock. Many valleys were first crossed with temporary wooden bridges called trestles. These were later replaced with solid fills.

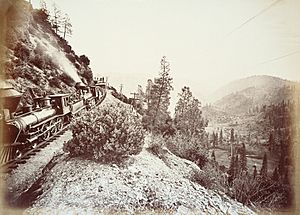

The route went down the eastern Sierras on the south side of Donner Lake. The Truckee River valley provided a good path. To speed up work, the Central Pacific hauled small locomotives and materials ahead. They worked through the winter of 1867–68 in the Truckee Canyon.

To keep the Sierra grade open in winter, 37 miles (60 km) of wooden snow sheds were built. These covered the tracks to protect them from deep snow and avalanches. Today, most of these wooden sheds are gone. Some concrete sheds and original tunnels are still used.

On June 18, 1868, the Central Pacific reached Reno, Nevada. They had built 132 miles (212 km) over the Sierras. From Reno, they crossed a "forty mile desert" and then followed the Humboldt River. Water for the steam locomotives came from wells, springs, or pipelines.

Near Promontory, the Central Pacific crews set a record. They laid 10 miles (16 km) of track in one day. This record still stands. The Central Pacific and Union Pacific raced to lay as much track as possible. The Central Pacific laid about 560 miles (900 km) from Reno to Promontory Summit in one year.

By May 1869, the Central Pacific had many freight cars and locomotives. They bought locomotives from the East and shipped them by sea. The CPRR route passed through towns like Newcastle, Reno, Winnemucca, and Wells. It connected with the Union Pacific at Promontory Summit. Later, the CPRR extended its tracks to Ogden, Utah. This made Ogden a major railroad hub.

Building the Railroad: The Hard Work

Labor and Construction Methods

Building the railroad needed a huge amount of effort. Most of the money came from selling government-backed bonds. The government also gave land for the right-of-way. This saved money and time. Engineers and surveyors planned the route. Many Union Pacific engineers were Civil War veterans. They knew how to build and maintain railroads.

After getting money and engineers, the next step was hiring workers. Most key workers had experience in railroad building. The engineers told the crews where and how to build. Coordinators made sure supplies arrived on time. Special teams worked on bridges, tunnels, and blasting. These teams often went ahead of the main track-laying crews.

The Central Pacific track-laying crew set a record. They laid 10 miles (16 km) of track in a single day. This was a huge achievement.

Besides laying track, other crews built stations. These stations provided fuel, water, and services for passengers and freight. Maintenance depots were built to fix equipment. Telegraph operators were hired for each station. They tracked trains to prevent accidents on the single track. Sidings were built so trains could pass each other. Fuel (coal or wood) and water towers were also needed for the steam locomotives.

Union Pacific's Workers

Most of the Union Pacific track was built by veterans of the Union and Confederate armies. Many recent immigrants also worked. Brigham Young provided about 2,000 Mormon workers. They built much of the road through Utah. However, Thomas Durant often failed to pay them as agreed. He was even held up by striking workers until he paid them.

Central Pacific's Chinese Workers

The Central Pacific faced a shortage of workers. Many people in California preferred to mine for gold or silver. Charles Crocker decided to try hiring Chinese immigrants. Many were from China, escaping poverty and war. They proved to be excellent workers. The Central Pacific then hired thousands more.

Chinese workers did most of the heavy manual labor. They used shovels, picks, and wheelbarrows. They also blasted through mountains. A Chinese "boss" often translated and managed the crews. Most Chinese workers planned to return to China after earning money. They were paid similar wages to unskilled white workers.

Much of the early work for the Central Pacific was building the roadbed through the Sierra Nevada mountains. This involved cutting through hills, filling valleys, building bridges, and digging tunnels. Once out of the mountains, construction was much faster.

Tunnels were blasted by hand-drilling holes and filling them with black powder. Later, nitroglycerin was used, which sped up work. The Central Pacific even had its own nitroglycerin plant. Chinese laborers operated this dangerous plant.

Chinese workers were vital in building 15 tunnels through the Sierra Nevada. They worked in shifts around the clock. One foreman, often Irish, would manage 30 to 40 Chinese men. They worked on drilling and removing blasted rock.

To keep the Central Pacific line open in winter, they built massive wooden snow sheds. These covered the tracks in areas prone to deep snow and avalanches. This work involved 2,500 men and many material trains. Masonry walls were also built to protect the wooden structures from avalanches.

Union Pacific's Challenges

Thomas Durant, a main investor in the Union Pacific, used his power to make extra money. He had a company called Crédit Mobilier do the construction. This company charged the Union Pacific much more than usual.

Construction on the Union Pacific started fast on the flat Great Plains. But it soon entered Native American lands. The railroad violated treaties. Native American groups began to attack the work camps. The Union Pacific increased security. They also hired hunters to kill buffalo. This was a threat to trains and a main food source for Native Americans. When Native Americans realized the "Iron Horse" threatened their way of life, they fought back.

Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Henry Sheridan were ordered to protect the railroad. They used harsh tactics against Native Americans. The buffalo population was greatly reduced. This pushed Native Americans onto reservations. Sheridan later admitted that the Native Americans were given no compensation for their land.

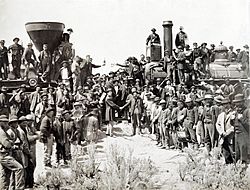

The "Last Spike" Ceremony

Six years after construction began, the Central Pacific Railroad from the west met the Union Pacific Railroad from the east. This historic meeting happened at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. The Union Pacific's engine was No. 119. The Central Pacific's engine was the Jupiter. Irish workers laid the last two rails for the Union Pacific. Chinese workers laid the last two rails for the Central Pacific.

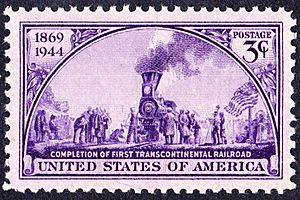

On May 10, 1869, the two engines met. Leland Stanford drove the ceremonial "Last Spike" (or golden spike). This joined the rails of the transcontinental railroad. The spike is now at Stanford University. Another golden spike is at the California State Railroad Museum.

This event was like the world's first live mass media event. The hammers and spike were connected to the telegraph line. Each hammer stroke was supposed to be heard as a click across the country. The actual hammer strokes were missed, so the clicks were sent by the telegraph operator. As soon as the golden spike was replaced with an ordinary iron spike, a message was sent: "DONE." Travel from coast to coast, which used to take months, was now reduced to just one week.

What Happened Next

Railroad Growth and Changes

When the last spike was driven, the railroad connected Omaha to Sacramento. To reach the Pacific, the Central Pacific bought the Western Pacific Railroad. On September 6, 1869, the first transcontinental passengers arrived at the Alameda Terminal. They then took a steamer to San Francisco. On November 8, 1869, the Central Pacific finished the rail connection to Oakland, California. From there, ferries connected passengers and freight to San Francisco.

The Central Pacific soon found it hard to keep the tracks open in winter. They tried snowplows. Then, they built many wooden snow sheds over the tracks. These mostly kept the tracks clear.

Both railroads worked to improve their lines. They built better bridges, laid heavier rails, and improved the roadbeds. The original track was laid quickly, so upgrades were needed. Once the railroad was running, it was easier to bring supplies by train.

The Union Pacific connected Omaha to Council Bluffs in 1872. This was when the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge was finished.

Other railroads also grew. In 1869, the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad finished the first bridge over the Missouri River in Kansas City. This connected to the Kansas Pacific trains. In August 1870, the Kansas Pacific connected to the Denver Pacific Railway. This completed the first true Atlantic-to-Pacific railroad in the United States. Kansas City became a major rail center.

On June 4, 1876, an express train called the Transcontinental Express arrived in San Francisco. It took only 83 hours and 39 minutes from New York City. Just ten years before, this trip would have taken months.

The Central Pacific later merged with the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1885. The Union Pacific bought the Southern Pacific in 1901 but had to sell it due to monopoly concerns. The two railroads reunited in 1996.

In 1942, the rails at Promontory Summit were removed to be recycled for World War II. This started with a ceremony to "undrive" the Last Spike.

The Crédit Mobilier Scandal

Despite the railroad's success, the Union Pacific faced problems. Details came out about how Crédit Mobilier had overcharged the Union Pacific for construction. This became a huge scandal in 1872. It involved many politicians.

Thomas Durant had created the scheme. Crédit Mobilier charged the Union Pacific much more than the actual cost of work. President Lincoln asked Congressman Oakes Ames to fix things. Ames became president of Crédit Mobilier. He gave stock options to other politicians while continuing the overcharges. The scandal broke in 1872. Ames was censured by Congress.

Durant later left the Union Pacific. Jay Gould became the main owner.

What Remains Today

Parts of the historic line are still used today. This is especially true through the Sierra Nevada Mountains and canyons in Utah and Wyoming. The original rails have been replaced, but the lines still follow the original path. From Interstate 80 in California, you can see parts of the original Central Pacific line and the old snow sheds.

In areas where the original line was replaced, like in Utah, the old roadbed is still visible. This includes the Big Fill east of Promontory.

In 1957, Congress created the Golden Spike National Historic Site. It was renamed the Golden Spike National Historical Park in 2019. The site has replica engines of Union Pacific No. 119 and Central Pacific Jupiter. These engines are sometimes run for the public.

Modern Passenger Service

Amtrak's California Zephyr is a daily passenger train. It travels from Emeryville, California to Chicago. This train uses parts of the first transcontinental railroad from Sacramento to central Nevada.

The Railroad in Popular Culture

The meeting of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific lines in 1869 inspired Jules Verne's book Around the World in Eighty Days.

The 1924 silent movie The Iron Horse shows the strong national pride behind the project. Some Chinese laborers who worked on the railroad even helped cook for the film crew.

Other movies about the railroad include:

- The 1939 film Union Pacific, directed by Cecil B. DeMille.

- The 1962 film How the West Was Won, which has a famous scene of a buffalo stampede over the tracks.

- The 1968 Western Once Upon a Time in the West.

Books about the railroad include:

- Graham Masterton's 1981 novel A Man of Destiny.

- Mary Ann Fraser's 1993 children's book Ten Mile Day.

- Kristiana Gregory's 1999 book The Great Railroad Race.

The railroad also appears in:

- The 1999 Will Smith film Wild Wild West.

- The 2000 film The Claim.

- The 2002 DreamWorks Animation movie Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron.

- The 2004 BBC documentary series Seven Wonders of the Industrial World.

- The TV series Hell on Wheels.

- The 2013 Walt Disney movie The Lone Ranger.

In 2015, a Lego model of the Golden Spike Ceremony was submitted to the Lego Ideas website.

Images for kids

-

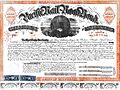

1864 advertisement for the opening of the Dutch Flat Wagon Road.

-

Grenville M. Dodge wearing a major general's uniform.

See also

In Spanish: Primer ferrocarril transcontinental de Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Primer ferrocarril transcontinental de Estados Unidos para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |