William de Ros, 6th Baron Ros facts for kids

William Ros, 6th Baron Ros (born around 1370 – died November 1, 1414) was an important English nobleman, politician, and soldier in the Middle Ages. He was the second son of Thomas Ros, 4th Baron Ros and Beatrice Stafford. William inherited his family's lands and title, Baron Ros, in 1394. These lands were mostly in Lincolnshire. Soon after, he married Margaret, the daughter of Baron Fitzalan. The Fitzalan family was very powerful and did not like King Richard II. This might have made King Richard think less of William Ros.

The late 1300s were a time of big political problems in England. In 1399, King Richard II took away the lands of his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, and sent him away from England. A few months later, Bolingbroke came back to England with an army. William Ros quickly joined Bolingbroke's side. King Richard lost the support of his people. Ros was with Henry when Richard gave up his throne. Henry Bolingbroke then became King Henry IV. Ros later voted in the House of Lords to have the former king imprisoned.

William Ros did very well under the new King Henry IV. He achieved much more than he ever did under King Richard. Ros became a key helper and adviser to King Henry. He often spoke for the king in parliament. He also joined Henry in his military campaigns. Ros was part of the invasion of Scotland in 1400. Five years later, he helped stop a rebellion led by Richard Scrope, who was the Archbishop of York.

In return for his loyalty, Ros received many gifts and benefits from the king. These included lands, money, and the right to look after young heirs and arrange their marriages. Ros was a valuable adviser and ambassador for King Henry. He was also a very rich man. He often lent large amounts of money to the king, who was often short on cash. Even though he was important in government, Ros could not avoid local conflicts. In 1411, he had a land dispute with a powerful neighbor in Lincolnshire. He barely escaped an ambush. He asked for help from parliament and received it. A historian from the 1900s described Ros as a very wise and patient person for his time.

King Henry IV died in 1413. William Ros did not live much longer. He had only a small role in government during his last year. He might not have been a favorite of the new king, Henry V. Henry V, when he was Prince of Wales, had argued with his father a few years before. Ros had supported King Henry IV over his son. William Ros died at Belvoir Castle on November 1, 1414. His wife lived for another 24 years. His son and heir, John, was still a child. John later fought at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. He died without children in France in 1421. The title of Baron Ros then went to William's second son, Thomas. Thomas also died while serving in the military in France, seven years after his brother.

Contents

Early Life and King Richard II

We do not know the exact date William Ros was born. In 1394, he was said to be about 23 years old. This means he was likely born around 1370. The Ros family was very important in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. Historian Chris Given-Wilson called them one of the greatest noble families of the 1300s. They never became earls, but they were still very powerful. William's father was Thomas Ros, 4th Baron Ros. He fought in the Hundred Years War under King Edward III. He was especially involved in the Battle of Poitiers in 1356.

William also had two younger brothers, Robert and Thomas. We do not know much about them. William's older brother, John, became the fifth Baron Ros when their father died in 1384. John's career was short. He fought for the new king, Richard II, in Scotland in 1385–86. He also fought in France the next year. In the early 1390s, John went on a religious journey to Jerusalem. He died in Paphos on August 6, 1393, on his way back to England. John and his wife had no children. So, William was next in line to inherit the title. He became the sixth Baron Ros. By this time, he had been made a knight and joined the King's Privy Council.

Taking Over the Family Lands and Marriage

The Ros family lands were mainly in eastern and northern England. William officially took control of them in January 1384. This gave him a lot of power in Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, and eastern Yorkshire. At this time, the family lands also had to support two dowager baronesses. These were his deceased brother's wife, Mary, and their mother, Beatrice. Mary died within a year of her husband. Her large inheritance was divided among her Percy relatives. Ros received her dower lands, which included the old Barony of Helmsley. Beatrice, his mother, lived longer than William. She was given her dower lands in December 1384. This meant William would never fully control a large part of the land, mostly in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Ros officially took possession of his lands on February 11, 1394. This included looking after some Clifford family estates. His sister had married Thomas de Clifford, 6th Baron de Clifford around 1379. William held these lands until their son, John, became an adult around 1411. Ros married Margaret, daughter of John Fitzalan, 1st Baron Arundel and Eleanor Maltravers, soon after he inherited. She was already receiving money from King Richard II. This was because she had been part of the household of Richard's queen, Anne of Bohemia, who had recently died.

William's wife gave him a useful connection to the king. It was also helpful that his wife's father had recently died. This made the Earl of Arundel his brother-in-law. These new connections and the higher political standing they brought might explain the royal grants he soon received. These included Clifford manors in Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Worcestershire. Ros attended the king's wedding to his second wife, Isabella of Valois, in Calais in December 1396. His wife's grandfather died the next year. She then became Lady Maltravers in her own right.

Even though Ros received some royal favor, he might not have been doing as well as expected. Historian Charles Ross suggests that William's connections to the Fitzalan family might have worked against him with the king. Arundel was a strong opponent of King Richard. Marrying into this family, who were not popular with the king, might explain why Ros was given few official jobs by Richard. Ross said it seemed "strange" that a rich young lord, who later proved to be active and able, had little public work under King Richard II. Ros's situation did not change until King Henry IV, a political ally of Arundel, came to power in 1399.

Changing Kings: Henry IV's Reign

John of Gaunt, the most powerful noble in England, died in February 1399. King Richard and Bolingbroke had argued the year before. Richard had sent Bolingbroke away from England for six years. Instead of letting Bolingbroke inherit his father's lands and titles, King Richard took them for himself. Richard said Bolingbroke's exile was now for life. He also said Bolingbroke could only get his inheritance back if the king allowed it.

Bolingbroke, who was in Paris, joined forces with Thomas Arundel. Arundel had been the Archbishop of Canterbury. He was also Ros's wife's uncle. He had lost his job and been sent away since 1397. With Arundel and a small group, Bolingbroke landed in Yorkshire in June 1399. William Ros quickly joined Bolingbroke's army with a large group of his own men. Many other northern nobles also joined. King Richard was fighting in Ireland at the time. He could not defend his throne.

Henry first said he only wanted to get back his rights as Duke of Lancaster. But he quickly gained enough power and support, including Ros's, to claim the throne. He was then declared King Henry IV. In June, Ros was at Berkeley Castle when Henry and Richard met for the first time since Henry was exiled. Ros also saw their last meeting on September 6 at the Tower of London. There, Richard gave up the throne.

Henry IV becoming king greatly improved Ros's and the Fitzalan family's fortunes. Ros now had strong connections at the royal court and was quite close to the new king. Unlike how Richard treated him, Ros's loyalty to Henry earned him many royal benefits. In the first parliament of the new king, held in October 1399, Ros was chosen to review petitions. He was also one of the lords who voted to imprison Richard. Richard later died in Pontefract Castle. Ros's important new role in government was clear in December 1399. He was appointed to Henry's first royal council.

We do not know why Ros joined Bolingbroke's invasion so quickly. But for most of Henry's new allies, we can only guess their reasons. Ros might have been upset by Richard's poor treatment of Gaunt and Bolingbroke. His own lack of promotion under Richard was also likely a reason. Whatever his reasons, Ros and his father had always been loyal to the Lancastrian family. His father had been one of John of Gaunt's earliest followers. Ros had also worked for Gaunt in the late 1300s. He traveled with the duke and did business for him many times. For his service, Ros received money each year. He was one of only two special knights Gaunt kept.

Local Government and Challenges

William Ros was an active royal official in local government. He became a leading figure in politics in the north Midlands and Yorkshire. He often led royal commissions there. He was often appointed as a justice of the peace, especially in Leicestershire. Ros also served the king in other ways. In 1401, he helped the king try to increase royal income. He was chosen to talk to the House of Commons. His job was to convince them to agree to a tax for the king's planned invasion of Scotland. Ros and the Commons met in Westminster. He stressed how much the king spent defending the Welsh and Scottish Marches.

The king and the Commons were careful with each other. The king did not want to set a bad example. The Commons were usually wary of the House of Lords. Six years later, Ros did a similar job. He was on a committee with the Duke of York and the Archbishop of Canterbury. They listened to the Commons' complaints. The discussions led to an argument. The parliament records say the Commons were "hugely disturbed." This disturbance was probably because of something Ros said. It might explain why the Commons did not want to meet him or his committee. Ros's goal was to get the Commons to agree to a large tax. He also tried to get them to agree to as few new freedoms as possible. He was an experienced parliament member. He attended most parliaments from 1394 to 1413.

King Henry faced problems almost from the start of his reign. Most of these were about money. By 1402, his treasury was empty. Around this time, Ros was appointed Lord Treasurer. This showed the king trusted Ros more. Ros held this job for the next four years. He could not greatly improve Henry's money situation. Relations with the Commons got worse. During the 1404 parliament, the speaker, Arnold Savage, spoke to the king about his lack of money. Savage said the king's constant demands for taxes could be fixed by paying fewer annuities (yearly payments). Savage also criticized an unnamed minister for owing royal creditors a lot of money.

The House of Commons' unhappiness was clear to the king. He responded within a week. He sent Ros, with Chancellor Henry Beaufort, to the Commons. They brought a full list of the king's money needs. Henry's government continued to struggle with low income. The treasury relied on a small group of loyal people, including Ros. He lent a lot of money to the king. He even gave up his councilor's salary for a time to help the royal finances.

Ros also served a lot in the military. In 1400, he agreed to bring a ship with 20 soldiers and 40 archers for Henry's Scottish invasion. The campaign did not go as planned, but Ros was part of it. Back in Westminster, he continued as a councilor. He also took part in Henry's Great Council the next year. In 1402, Owain Glyndŵr started a rebellion in Wales. This affected Ros personally. His brother-in-law, Reginald, Lord Grey of Ruthin, was captured by Glyndŵr. The Welsh demanded a large ransom from the king. The king agreed to pay. Ros, because he was related to Grey, also agreed to help. He led the group that talked with Glyndŵr about the payment and Grey's release.

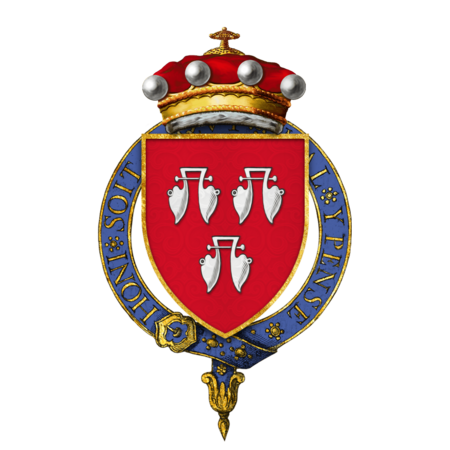

Ros was also chosen for the Order of the Garter in 1402. Two years later, he was given money each year for being the king's follower. In May of that year, another rebellion started in the north. It was led by Richard Scrope, Archbishop of York, and Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland. Ros was part of a group of loyalists who helped the king's cousin, Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland, stop the rebellion. Henry trusted Ros to meet with Westmorland, who led the king's armies in the north. Ros was probably chosen because he knew the area well. The mission was a success. Ros saw the Earl of Northumberland give up Berwick Castle to the king. He also sat on the group that sentenced Scrope to death without a trial in June 1405. When the king arrived in York to see the rebels executed, Ros brought Percy's agreements to him.

The next year, the king's health got much worse. In the 1406 parliament, Henry IV agreed that a Grand Council should be set up to help him rule. Ros was on the list of people to be appointed to this council. He attended its meetings in late 1406. He also continued to speak for the king to the Commons. He probably helped the Lord Chancellor during a difficult time because of the King's illness.

Royal Favor and Trust

Throughout Henry's reign, Ros was "high in the King's confidence." He held very trusted positions. Historian Mark Arvanigian says Ros was "clearly a reliable and trusted servant, as well as being a reasonably talented administrator and royal councillor." Henry continued to rely on loans to carry out his plans. Ros's loans helped pay for the Calais army. Unlike many others, Ros was promised repayment. This showed how much the king favored him.

By 1409, for example, he was given profitable jobs as master forester and constable of Pickering Castle. These jobs increased his influence in the region. They also allowed him to appoint others and give out favors himself. In October of that year, Ros paid money to look after Giffard family lands. John Tuchet, Lord Audley died in December. Ros was given Audley's lands while the Audley heir was a child. Ros also paid a large sum to arrange the heir's marriage. These grants were in addition to his yearly salary. He also had a manor where he and his men could stay when he was in the south for royal business. Ros remained an active councilor. He also took on important military and diplomatic roles. He was one of Henry's few advisers who stayed close to the king even when the royal council was not meeting.

Ros remained in the King's favor until the end of Henry's reign. As a trusted adviser, in 1410, he took part in an important trial. The year before, a church court had found John Badby guilty of Lollardy, a religious belief. Badby was given a year to change his mind. He refused. On March 1, 1410, Badby was brought before a meeting. Ros and other nobles found Badby guilty. He was then burned to death in Smithfield.

Local Problems and Solutions

After the death of the Earl of Stafford in 1403, Ros was the main noble in Staffordshire. He was in charge of keeping the king's peace. This was a time known for widespread lawlessness. Nobles and gentry often fought among themselves. In 1411, Ros helped stop a tense situation that could have turned into a fight between local gentlemen. This was only a temporary stop. The next year, Ros helped arrange another agreement between them.

In early 1411, Sir Walter Tailboys caused a riot in Lincoln. He attacked the sheriffs, killed two men, and waited outside the city to ambush people. The citizens of Lincoln asked the king for justice. They specifically asked that Ros and his relative, Lord Beaumont, investigate. They found in favor of the Lincoln citizens. Tailboys was ordered to keep the peace and pay a large sum of money. Because of his efforts, historian Simon Payling said that Ros's "reputation for fair-mindedness" made him popular for settling disputes.

Even with his skill at solving problems, Ros was not free from local conflict. In 1411, he had a dispute with his neighbor, Sir Robert Tirwhit, in Lincolnshire. Tirwhit was a new royal judge and well-known in the county. They argued over rights to graze animals and cut hay in Wrawby. A meeting was set up with Justice William Gascoigne. Tirwhit, however, brought about 500 men. Ros kept to the agreement and brought only a few companions.

Ros and his friends escaped Tirwhit's ambush unharmed. On November 4, 1411, Ros asked parliament for justice. The case was heard by important figures. They found strongly in Ros's favor. Tirwhit was ordered to give Ros wine and provide food and drink for the next meeting. There, he would publicly apologize to Ros. In his apology, Tirwhit admitted that Ros, as a nobleman, could have also brought an army but chose not to.

Final Years and Death

The King's health continued to get worse. But in 1411, he was well enough to form a new council of loyal advisers. This council purposely did not include his son, Prince Henry, or his son's friends. Ros, who was a "reliable royalist," was on this council for the next 15 months. He was with other loyal officials. Ros and the others now signed important government documents. Historians A. L. Brown and Henry Summerson note that "at the end of his reign, as at its beginning, Henry placed his trust principally in his Lancastrian retainers."

Henry IV died on March 20, 1413. William Ros did not play a big role in government after this. He probably attended his last council meeting in 1412. Charles Ross suggests that the new king, Henry V, did not particularly favor him. Ross believes this was because Henry V did not trust his father's loyalists. He felt they kept him from power during his father's illness. Whether Henry excluded him or not, Ros lived only 18 months into the new reign.

Ros died at Belvoir Castle on November 1, 1414. He had written his will two years earlier. He added an update in February 1414. He died a very rich man. He had one of the highest incomes in Yorkshire.

Three of William Ros's children fought in the later part of the Hundred Years' War. John, his oldest son, was born in 1397. He was still a child when Ros died. The Earl of Dorset, the king's cousin, was given control of the Ros family lands. Before he inherited, John traveled to France with the new king in 1415. He fought at the Battle of Agincourt when he was 17 or 18. He died in 1421 at the Battle of Baugé in France. William Ros's second son, Thomas, was only 14 when John died. He fought at the siege of Orléans in 1428. He died after a fight outside Paris two years later. Thomas's son, also named Thomas, became the 9th baron. He played an important role in the Wars of the Roses. He fought for the Lancastrian king, Henry VI. He was beheaded after losing a battle in 1464. Ros's wife, Margaret Fitzalan, lived until 1438. She became a lady-in-waiting to the new queen, Catherine of Valois, in 1420.

Family and Gifts

William Ros and his wife, Margaret Fitzalan, had four sons: John, Thomas, Robert, and Richard. They also had four daughters: Beatrice, Alice, Margaret, and Elizabeth. Ros also had an illegitimate son, John.

Historian Charles Ross suggests that Ros was a "just and fair-minded" man. This is shown by the gifts he left in his will. His oldest son, John, inherited his father's title and lands. He also received his father's armor and a gold sword. His third son, Robert, who Ross says was "evidently his favorite," also inherited some land. Ros made this special gift for Robert from John's inheritance. His three younger sons (Thomas, Robert, and Richard) received a third of Ros's goods. Thomas, as a younger son, was meant to have a career in the church. Ros's wife, Margaret, received another third of his goods. His illegitimate son, John, received money for his care. Loyal followers received benefits. Ros also left large sums of money to his "humbler dependents," like the poor people on his lands. His executors, including his son John, received money for their work. Ros was buried in Belvoir Priory. A stone statue of him was placed in St Mary the Virgin's Church, Bottesford. Seven years later, after his son John died, a statue of John was placed next to his. William Ros left money to pay ten priests for eight years to educate his sons.