Wings Over Jordan Choir facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wings Over Jordan Choir

|

|

|---|---|

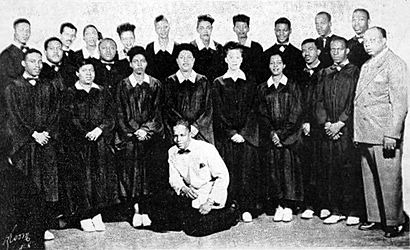

1939 publicity photo of the Wings Over Jordan Choir. The Rev. Glenn Thomas Settle is standing at front right, with "WGAR" and "CBS" microphones at opposite ends.

|

|

| Background information | |

| Also known as | The Negro Hour Choir |

| Origin | Cleveland, Ohio, United States |

| Genres | Spirituals |

| Instruments | A capella |

| Years active | 1935–1978 |

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts |

|

| Past members | See list of personnel |

| Other names | The Negro Hour |

|---|---|

| Genre | Spirituals |

| Running time | 25 minutes |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Language(s) | English |

| Home station | WGAR, Cleveland, Ohio |

| Syndicates |

|

| Starring | Wings Over Jordan Choir |

| Announcer | Wayne Mack (all WGAR-produced episodes) |

| Created by |

|

| Recording studio | Hotel Statler (WGAR main studio); CBS and Mutual affiliates |

| Other studios | Euclid Avenue Baptist Church, Cleveland, Ohio (summer 1941) |

| Original release | July 11, 1937 – December 25, 1949 |

| No. of episodes |

|

| Audio format | Monaural sound |

| Opening theme | "Go Down Moses" |

| Sponsored by |

|

The Wings Over Jordan Choir was an African-American a cappella (singing without instruments) spiritual choir from Cleveland, Ohio. The choir became famous for its weekly religious radio show, Wings Over Jordan, which was created to feature the group's music.

The radio show started in 1937 on Cleveland radio station WGAR as The Negro Hour. It later aired on the Columbia Broadcasting System from 1938 to 1947. Then it moved to the Mutual Broadcasting System until 1949. Wings Over Jordan was a groundbreaking show. It was the first radio program produced and hosted by African-Americans to be broadcast across the country. The show was easy for people in the Deep South to listen to. It featured important Black church and community leaders, scholars, and artists as guest speakers. It became one of the most popular religious radio shows in the United States. It also reached an international audience through shortwave radio on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the Voice of America (VOA), and Armed Forces Radio. The program helped WGAR and CBS win the first Peabody Awards in 1941.

The choir was founded in Cleveland by Baptist minister Glenn Thomas Settle (1894–1967). The group performed concerts all over the country. They often challenged unfair segregation laws. They also toured with the USO to support American soldiers during World War II and the Korean War. The Wings Over Jordan Choir was known as one of the world's greatest Black choirs. It is seen as an important part of the civil rights movement. It also helped keep traditional spirituals alive by sharing them with many people. Other groups using the same name appeared in the 1950s. A tribute choir in Cleveland has been performing since 1988.

Contents

History of the Choir

How the Choir Started (1935–1938)

Cleveland Roots

Members of the "Wings Over Jordan" choir, prior to the organization of the group, were mainly members of the Gethsemane Church choir. Few of the vocalists have had any formal musical training. Men in the group were house painters, garage attendants, chauffeurs, WPA workers and elevator operators, while women were employed as maids, cooks and seamstresses.

The Wings Over Jordan choir began at Gethsemane Baptist Church in Cleveland. Rev. Glenn Thomas Settle led the group. Settle was born in Reidsville, North Carolina, in 1894. His family were sharecroppers (farmers who paid rent with a share of their crops). His grandfather was an African prince who was captured and sold into slavery. Settle moved to Cleveland in 1917. He studied at the Moody Bible Institute at night. During the day, he worked with metals in a factory.

Settle became the pastor of Gethsemane Church in 1935. The church was having financial problems, but Settle helped it become strong again. Many church members were families who had moved from the South. The church choir had strong, natural voices, even though most singers had no formal training. They worked as laborers, maids, and elevator operators. Settle created an a cappella choir with singers from his church and Central High School. James E. Tate became the choir's first director.

The choir sang spirituals, which are songs that tell the story of African-Americans during slavery. These songs became popular again during the Great Depression. Settle wanted to keep these spirituals true to their original form. Their performances were often very emotional. Spirituals were sometimes called "sorrow songs," but they also offered hope for a better future. Singing these songs helped choir members feel better. Settle's granddaughter later said spirituals were like songs of sadness, while gospel songs were about hope and new beginnings. The choir quickly became popular in Cleveland and started touring.

WGAR's The Negro Hour

Settle wanted to get the choir on the radio. He met Worth Kramer, a program director at Cleveland radio station WGAR. Kramer was very impressed by the choir's singing. He quickly started a new show called The Negro Hour on July 11, 1937. Settle's choir provided the music for this show.

The Negro Hour also featured guests who talked about issues important to Black people. The first guests included Cleveland's mayor, Harold Hitz Burton. This was the first known radio program produced and directed by African-Americans. It was also the first show to feature Black people in a respectful way, not as silly characters. Kramer became a strong supporter of the choir. He believed spirituals were a true form of early American music.

Going National on CBS

WGAR joined the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) in September 1937. The success of The Negro Hour caught CBS's attention. The choir was given a special 15-minute show on November 9, 1937, called Wings Over Jordan. This show helped CBS executives hear the choir and consider a regular program. CBS decided to broadcast Wings Over Jordan across the country starting January 9, 1938. This made it the first show produced and hosted by African Americans to be broadcast nationwide on a radio network.

The choir then officially changed its name to "Wings Over Jordan." Settle never fully explained the name's origin. Some believed it referred to the Christian idea of crossing the River Jordan at death. Others thought it came from Settle's way of using stories in his sermons. Many spirituals used "wings" to mean escaping slavery, and "The River of Jordan" was a common song. The name stuck with the choir for 30 years.

Broad Popularity (1938–1942)

Worth Kramer's Leadership

When the show went national, Settle asked WGAR's Worth Kramer to direct the choir. Kramer was supposed to stay for only four weeks, but he ended up staying for four years. He was very good at radio production and understood music well. He helped the choir, many of whom could not read sheet music, learn their songs.

Kramer also spoke out against swing band leaders who used spirituals in ways he felt were disrespectful. He said it was wrong to "jive" sacred songs. Some people felt Kramer received too much credit for the choir's success. However, many believed he helped the choir become famous and get their show on CBS. Settle's granddaughter said Kramer "opened doors that my grandfather could not get in."

Extensive Concert Tours

Wings Over Jordan became CBS's most important sustaining program. This meant CBS paid for all the airtime, so the show didn't need commercials. It was very popular, with an estimated ten million listeners each week. People in Black neighborhoods in Cleveland would often tune their radios to WGAR, even putting them on porches so others could listen.

In the summer of 1938, the choir went on its first big concert tour. They visited cities in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama. Settle made sure choir members could stay with Black families if needed. He refused to let the choir perform for segregated audiences. Sometimes, they were even arrested for breaking Jim Crow laws (unfair laws that separated people by race). They would then broadcast from historically black colleges and universities.

If I could hear singing like that every morning, my day would be a lot happier.

The choir performed over 150 concerts in their first 18 months on CBS. They started getting fan mail from all over the country. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a big fan. She invited some choir members to the White House in 1938. A concert in Baltimore in 1939 drew over 18,000 people. The choir became a nonprofit organization in 1939. By 1941, they had offices in several cities and were called "perhaps one of the Nation's largest Negro enterprises."

A white promotional director named Neil Collins helped the choir with their tours. He visited radio stations and arranged lodging in segregated towns. He helped them get concerts and publicity that might not have been possible otherwise. The choir often performed daily, sometimes three times a day. In March 1940, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia gave the choir a key to the city after they sang in his office. He said, "if I could hear singing like that every morning, my day would be a lot happier." The largest audience for a Wings concert was 75,000 people in Cleveland in 1940.

Guest Speakers

Many times, particularly during the '30s and '40s, when there were numerous lynchings or killings of African-Americans in the South, these stories were not carried in depth by the white media. A number of the speakers ... (Rev. Settle) would bring them on, and they would use his Sunday-morning broadcasts as an outlet to help let the world know what was happening and the injustices being done in many areas.

The guest-speaker part of the show became a five-minute segment on CBS. Speakers could broadcast from different cities. Settle carefully planned his introductions to connect the songs with the guest speakers' messages. Guests included local church leaders, famous people, politicians, and important scholars. Hattie McDaniel, the first Black person to win an Academy Award, appeared on the show in 1940. Historian Carter G. Woodson and civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune were also guests.

These distinguished Black artists and scholars on the program were revolutionary. They broke the color barrier in radio. For the first time, Black people on national radio spoke openly about racial problems, like taking away voting rights or other serious injustices. Because Wings Over Jordan was not funded by commercials, the speakers could talk freely without fear of upsetting sponsors. This helped introduce these important issues to a wider audience.

International Reach

The program was broadcast live on Sunday mornings. Its start time changed a few times, eventually settling at 10:30 a.m. Eastern Time. This later time was meant to help listeners on the West Coast. Settle even suggested that churches broadcast the program as part of their Sunday school. The choir also had an extra 15-minute weekday program in 1941. They broadcast these shows from Cleveland's Euclid Avenue Baptist Church because it had more space than the WGAR studios.

The choir's fame spread internationally in September 1938. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) started broadcasting the program. By 1939, the show was available in Canada, Mexico, South America, India, and other places. The choir received messages from many of these countries. The show was also sent to Europe as part of a "Friendship Bridge" between Great Britain and the U.S. In 1942, CBS chose the choir to be part of its educational series, Columbia School of the Air, which was broadcast across North and South America.

Awards and Records

In January 1941, the choir signed a big contract with Alber-Zwick Corporation, a talent management company. The company planned for the choir to tour the West Coast, South America, and other parts of the world. They even considered film appearances.

The program received its biggest honors when WGAR and CBS won the first George Foster Peabody Awards in 1941. WGAR won for serving Cleveland's diverse communities, with Wings Over Jordan specifically mentioned. CBS won for its public service at the network level. The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) said Wings was the reason for both awards.

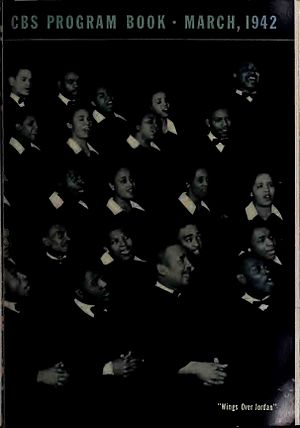

The New York Public Library's Schomburg Collection added Settle and Wings Over Jordan to its Honor Roll of Race Relations. This award recognized people and groups who improved race relations. Settle was honored in 1939, and the program itself was honored in 1941 for reaching more listeners than any other show of its kind. CBS even featured the choir on the cover of its March 1942 program guide.

The choir signed a recording deal with Columbia Records' Masterworks label in April 1941. They released a four-disc album the following May. Worth Kramer, the director, left his position in December 1941 to manage another radio station. Former singers remembered him fondly, saying the choir followed his direction perfectly.

The War Years (1942–1946)

Office of War Information Alliance

The best contributions radio can make to meeting the entire problem (of low morale among blacks) is by remembering Negroes whenever a program is being worked out on which they or their contributions can be included—and included unostentatiously. Many programs are already doing a constructive job in this direction. Some, on the war, have included mention of Negro heroes. Some, on production, have included Negro workers. Others have drawn attention to outstanding Negro cultural contributions to our civilization. All this is a good start—but only a start.

The United States entered World War II after the Attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Future guest speakers on Wings talked about topics like "This troubled world today" and "The meaning of democracy." The United States Office of War Information (OWI) made Wings Over Jordan an official source for news about Black military personnel. The program showed how Black people contributed to the war effort. By October 1942, the OWI provided guest speakers and news updates for Wings. The choir also recorded music for the Voice of America (VOA) and the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) for soldiers overseas.

The U.S. government was worried that enemy countries might try to use racial tensions to cause problems. Archibald MacLeish, a director at the OWI, asked radio stations to create programs that showed the contributions of Black Americans. He wanted people to understand that "among the 130,000,000 Americans fighting this war for survival, there are 13,000,000 liberty-loving Negroes doing everything they can to win."

We Negros shall face tyranny where ever it exists ... and when we have finished assisting America in the battles for human freedom (in Europe and the Pacific Islands), we shall be no less vigilant, no less determined, in breaking off the shackles of oppression form the oppressed here at home. For this is our mission, our destiny, throughout the world. We are the measurements of freedom, the storm troopers of the Rights of Man.

Sometimes, guests on the program talked about difficult topics related to the war. Edwin B. Jourdain, Jr., spoke about racial discrimination in the armed forces in November 1942. He supported the Double V campaign, which encouraged Black Americans to fight for democracy overseas and at home. He said Black people would fight against oppression everywhere. The parents of Doris Miller, a Black hero who received the Navy Cross for his bravery at Pearl Harbor, were also honored guests on the show.

Changes and Adaptations

After Worth Kramer left, the choir needed a new conductor. Frederick D. Hall became the temporary director, with Gladys Olga Jones as his assistant. Jones later took over as director. She had studied music and worked with a church choir in Louisiana. The choir also welcomed five new singers. Even though many original members stayed, the choir now had singers from 11 different states. Jones's time as conductor was short, and Joseph S. Powe replaced her by October 1942.

When this war is over, there shall be no North or South, white or colored, but just all united loyal citizens of the United States.

The choir continued to perform many concerts. A tour in the Deep South included a concert in Houston in February 1943 that was delayed because so many people came. The choir took a long vacation in July 1943, their first in over five years. They used this time to fix up their tour bus, adding things like cooking facilities and restrooms.

Hattye Easley, a popular soloist, became the new conductor after Joseph S. Powe left to join the United States Navy. In December 1943, Settle hired Maurice Goldman, a famous composer, as the choir's permanent conductor. Goldman was the choir's second white director, with Easley as his assistant. Settle hoped Goldman would help the choir tour the world after the war.

European USO Tour

The fame of Wings Over Jordan has not been confined to this musical organization, but has reflected favorably upon the city of Cleveland, and upon Gethsemane Baptist Church itself. Few churches in the nation are better known than this one ... Any church would be proud of the honor to have its pastor on a USO tour, bringing joy and inspiration to millions of soldiers lonely for home and peace.

The choir's biggest role in the war effort came in February 1945. The United Service Organizations (USO) chose them to entertain U.S. soldiers for six months. The USO was created in 1941 to boost the spirits of military personnel. Even though the USO sometimes followed segregation rules, they started arranging shows for Black troops. The choir was the first religious music group chosen for this, and the largest group of entertainers sent overseas.

The Wings Over Jordan radio show went off the air for a while after 372 continuous Sunday broadcasts. The choir, along with Settle and business manager Mildred Ridley, went to New York City to prepare for the tour. They received vaccinations, got uniforms, and obtained passports. For safety, their departure was kept a military secret. They sailed on the USS West Point in March 1945. All members were given the rank of captain for protection if they were captured. News of President Roosevelt's death during the trip saddened everyone.

Their six-month tour of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations began on April 29, 1945. Soldiers in Italy even built a special venue for the choir called "The Wings Over Jordan Stadium." Settle said the choir was "setting things on fire" overseas. They visited famous places like Rome and Vatican City, even while performing almost every day. Soldiers loved their concerts, giving them long standing ovations and asking for encores.

With the MTO and ETO

We didn’t (travel) like Bob Hope with the pretty girls. We were (called) a foxhole unit, because we had to try to talk to ordinary soldiers who were fighting. We had to go to the hospitals where they were injured.

The choir often sang for the 92nd Infantry Division, an all-Black unit. They dedicated songs to the soldiers and sang spirituals that brought comfort. Settle believed soldiers wanted to reconnect with religion. The choir performed at V-E Day celebrations in May 1945. They were very popular with the soldiers and were offered a full six-month tour. The choir even performed at a special ceremony in Genoa, Italy, in June 1945. They sang for 5,000 servicemen and city residents. This was unusual for an occupied European nation.

Mildred Ridley said the choir often visited hospitals with wounded soldiers. They ate and socialized with the G.I.s, using humor to cheer them up. Settle and the choir received awards from the military for their excellent service and patriotism.

Well, we've bounced all over Italy, North Africa, Sicily, France, Belgium and Germany in a six by six truck and now these cushions are so soft, I'm afraid to sit down for fear I'll sink through one.

After their five-month tour in the Mediterranean, the choir immediately started a four-month tour in the European Theater of Operations (ETO). This extended their USO commitment to ten months. They flew to Paris after blackout restrictions were lifted, and the city looked beautiful. Settle called the Mediterranean tour "the grandest six months of our career." He prayed for every serviceman to return home for a lasting peace. The group traveled in a large truck with their equipment. Some performances were broadcast live over AFRS, including a Christmas program with famous entertainers. The ETO tour ended on January 27, 1946. The choir had performed in France, Belgium, and Germany.

While the choir was overseas, CBS had other prominent Black choirs perform under the Wings Over Jordan name. These shows were produced by Settle's son, Glenn Howard Settle. Groups like the Fisk University Choir and the Tuskegee Institute Choir filled in. The original choir returned to the U.S. in March 1946 after a year-long break. They were welcomed back with a big celebration concert in Cleveland.

Postwar Activities (1946–1955)

More Touring

After returning in February 1946, the choir began one of their biggest concert tours ever. Between April 1946 and April 1947, they traveled over 100,000 miles and performed for more than 250,000 people. They performed at famous venues like Madison Square Garden and the Hollywood Bowl. In January 1947, the choir gave its first college scholarship. By November 1946, they were fully booked for 1947 and much of 1948. The choir now used two buses for travel. During a concert in Rockingham, North Carolina, someone damaged one of their buses. Local business people helped the choir, and the person responsible was punished.

The choir returned to Cleveland in May 1947 for a benefit concert. However, Settle's long absences had caused problems with his church. He resigned as pastor, admitting he hadn't been active for over a year. Settle also changed the spelling of his first name to Glynn. He was admitted to a fishing club after catching a record-sized fish, becoming the club's first Black member.

August 1947 Walkout

I was planning to leave the choir soon, to accept a position as head of the music department at Albany State College ... when I told Rev. Settle of my feelings regarding his treatment of choir members, he denounced me bitterly. He told me that I was the worst conductor he had ever had. This, in spite of the fact that out of the 14 conductors he has had in ten years, I am the only one who was ever recognized by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

The CBS program remained popular, even after the USO tour break. On August 10, 1947, the show celebrated its 500th episode. Two weeks later, on August 24, 1947, the choir members refused to perform. They left a concert in San Diego and went to Los Angeles. Settle's son, Glenn T. Settle, Jr., called it a "revolt." Several concerts were canceled. The choir members said Settle treated them unfairly and paid them too little. They said he didn't give them vacation time and laid them off when they weren't touring. Singers typically earned $52.50 a week, and the conductor earned $150. This was the first time a walkout stopped an episode of Wings from being broadcast.

CBS Cancellation and Aftermath

Settle tried to get the singers to return, but only one agreed. He then dismissed all 17 singers and started looking for new ones across the country. Some original singers, like Lois Waterford and Olive Thompson, rejoined the new choir. CBS canceled the radio program after the October 12, 1947, broadcast. They offered the time slot to college choirs from Black universities. The choir then toured Mexico and performed with the San Antonio Symphony.

The choir remained popular in 1948, performing in 45 states and raising over $1 million for charities. Under their new conductor, Gilbert Allen, the choir signed a contract with RCA Records. Their first single, "Until I Found The Lord," was released in October 1948. Their most popular song from RCA was "Sweet Little Jesus Boy" and "Amen" in December 1948. "Amen" became a favorite at concerts and on future recordings.

A New Business Model

The radio program was brought back on the Mutual Broadcasting System on January 9, 1949. This new version was sponsored by the Treasury Department to promote United States Savings Bonds. Guest speakers still appeared, but they focused on the life stories of famous Black Americans. The choir traveled to different Mutual stations for their broadcasts. The Mutual show was eventually dropped at the end of 1949 when the Treasury Department stopped its sponsorship.

Around this time, the choir started a new way of doing business. Instead of charging admission, concerts were free, but people were encouraged to give donations. Some of the money went to the Spiritual Preservation Fund, which supported the Wings scholarship fund. Settle said this change was made to help fight against certain political ideas in America. Reviewers praised the choir for this "unselfish effort." However, many new singers joined the choir, and Settle did not always train them properly. This affected the choir's sound quality.

The USO invited Wings to perform for soldiers overseas again in December 1953. This time, they visited Hawaii, the Philippines, South Korea, and Japan. They performed for large crowds in South Korea, even in very cold weather. The choir also appeared on television in Japan several times. Settle said he wanted the choir to tour the world to continue fighting against certain political ideas. His wife, Elizabeth Carter Settle, joined him on this tour. She passed away in 1955. Settle later married Mildred C. Ridley, the choir's business manager, and moved to Los Angeles.

Later Performances (1955–1978)

"Satellite" Choirs and Reorganizations

Now, almost twenty years later, there is no Wings Over Jordan. From national and international tours, world recognition and musical artistry, the singers that were integral parts of this choir have gone their separate ways—some to fame and fortune, some to death, to prison; some to routine living and all to reminiscing.

Since the original choir members had left, Settle formed several smaller groups that used the "Wings" name. The Legend Singers of St. Louis were one of these groups. By 1957, these were organized into two main choirs: a West Coast group led by Settle and Frank Everett, and an East Coast group led by Clarence H. Brooks. These groups were meant to continue Settle's mission to preserve spirituals. They recorded several albums, including The World's Greatest Negro Choir (1958) and The World's Greatest Spiritual Singers (1960).

Both choirs continued to tour the country. However, in August 1964, a tour by the East Coast choir ran into trouble. Two concerts in Georgia were canceled when the choir didn't show up. This happened after local police stopped them, thinking they were involved in civil rights protests. Both choirs eventually stopped performing by the end of 1964. Los Angeles musician Leroy Hurte briefly reorganized the West Coast choir, but Frank Everett later took over again.

Settle's Death and Choir Decline

Settle continued to be involved with the choir until he passed away on July 16, 1967. After his death, the choir's activities slowed down a lot. A tribute concert was held for Settle in 1969. The choir also celebrated its 35th anniversary in 1971 with an awards banquet to raise money for a Settle memorial scholarship. The choir toured Japan in 1970 and 1972. Frank Everett's time as director ended in 1978. Settle's widow donated many documents and items related to Wings to the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center.

Many surviving members of the original choir often reunited. The first big reunion was in 1957, celebrating 20 years since the radio show began. An annual reunion started in 1971, led by former assistant director Willette Firmbanks Thompson.

Legacy

Historical Importance

Settle wanted the choir to help improve race relations through music and keep African-American spirituals authentic. The choir achieved both goals through their concerts and radio show. The original members were ordinary workers from a modest church. They learned spirituals by listening and singing, keeping the music pure. Unlike other popular groups, their songs were not changed by minstrel shows. Worth Kramer's open-minded beliefs helped the choir reach a wider audience. They got a radio show, performed for mixed audiences, and signed with a major record label. His musical knowledge also helped preserve spirituals in written form.

Support from important white figures, like First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, showed the choir's lasting impact on different races. The novel In the Heat of the Night is dedicated to Settle. Scholars believe Wings Over Jordan was an important step towards the civil rights movement that began in 1954. Spirituals were later embraced by civil rights leaders for their social and political power. Cleveland mayor Harold Hitz Burton, who was on the first Negro Hour show, later became a United States Senator and a Supreme Court Justice. He was part of the famous Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which ended segregation in schools.

Nearly Forgotten

Even though Wings Over Jordan was a very important radio show, it is not widely remembered today. Many historical records about broadcasting don't mention it. CBS also didn't mention Wings Over Jordan during its 50th-anniversary celebration in 1977.

KCBS-TV in Los Angeles created a documentary called Wings Over Jordan: We Remember in 1989. It was nominated for an NAACP Image Award. The Library of Congress chose the May 10, 1942, broadcast of Wings Over Jordan for preservation in its National Recording Registry in 2008. Worth Kramer, the choir's director, continued to work in radio after the war. He was remembered for his leadership of Wings Over Jordan and his commitment to good broadcasting. Wayne Mack, who introduced the WGAR Wings broadcasts, was also remembered for his role in the show.

"That which is worthy must be preserved"

The "Wings Over Jordan Celebration Chorus" was formed in 1988. It was created as a tribute to the original choir. Music teacher Glenn T. Brackens, whose grandmother was an original Wings singer, founded the choir. He grew up hearing stories about his grandmother's time in the choir. The tribute chorus had its first public performance in 1988, celebrating 50 years since the original show's national debut. It was so popular that more singers joined. The Wings Over Jordan Alumni and Friends (WOJAF) group was also created to support the chorus and connect former members. Brackens uses Settle's motto, "That which is worthy must be preserved," as the chorus's slogan.

The messages that they sang gave the black people hope. We still sing those songs, written by black writers, because we're still in that hope that one day we will be ... just ... people.

Unlike the original choir, the Celebration Chorus includes some gospel songs and sometimes uses a piano. Brackens believes this fits Settle's goal of preserving spirituals. Some people who prefer the original style disagree, but others see the changes as a tribute. The Celebration Chorus has members with direct ties to the original choir. Persie Ford, an original singer, joined the tribute chorus and supported it strongly. Settle's granddaughter, Teretha Settle Overton, is also a member. John Foxhall, a member of the original choir, was important in preserving the choir's history. The Celebration Chorus currently performs about three times a year.

Kenneth Franklin Slaughter, believed to be the last living member of the original Wings choir, passed away in 2014 at age 92. He often shared his experiences with the choir in talks and interviews. John Foxhall, who passed away in 2021 at age 94, was known for his long work with WOJAF and his efforts to preserve the choir's history.

Personnel

It is estimated that the original choir had between 40 and 50 members in 1937. Most were unmarried young men and women, aged 17 to 30. Because so many singers were part of the choir over the years, it is very hard to make a complete list of everyone who participated.

Discography

Singles

- 1945: "The Old Ark's A'Moverin'" (V-Disc 353A)

- 1945: "I Couldn't Hear Nobody Pray" (V-Disc 397A)

- 1946: "Deep River" / "Old Ship Of Zion" (Queen 4140)

- 1946: "Were You There?" / "Take Me To The Water" (Queen 4141)

- 1946: "I'm Rollin'" / "When You Come Out The Wilderness" (Queen 4142)

- 1946: "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" / "Trampin'" (Queen 4154)

- 1946: "My Lord's Gonna Move This Wicked Race" / "You Got To Stand The Test In Judgement" (Queen 4155)

- 1946: "Plenty Good Room" / "I Will Trust In The Lord" (Queen 4156)

- 1948: "Until I Found The Lord" / "He'll Understand And Say 'Well Done'" (RCA Victor 20-3128)

- 1948: "Sweet Little Jesus Boy" / "Amen" (RCA Victor 20-3242)

- 1948: "Just A Closer Walk With Thee" / "Pray On" (RCA Victor 22-0006)

- 1949: "Rock A-My Soul" / "Sweet Little Jesus Boy," (Sterling WOJ 1-2)

- 1953: "Wings Over Jordan Choir Vol. 1" (King EP-232)

- 1953: "Wings Over Jordan Choir Vol. 2" (King EP-233)

- 1953: "Wings Over Jordan Choir Vol. 3" (King EP-234)

- 1956: "Take Me To The Water" / "Hush Children, Somebody's Calling My Name" (Dial 1238)

Studio Albums

- 1942: Wings Over Jordan (Columbia Masterworks M-499).

- 1956: Amen (King LP-395-519).

- 1958: World's Greatest Negro Choir (Dial LP-5163)

- 1960: The World's Greatest Spiritual Singers (ABC-Paramount LP-338)

Compilation Albums

- 1958: An Outstanding Collection of Traditional Negro Spirituals (King LP-560)

- 1961: My Soul Is a Witness (Electrola E 41 295)

- 1974: Wings Over Jordan (ABC Songbird SBLP-246).

- 1978: Original Greatest Hits (King/Gusto K-5021)

- 2007: Trying to Get Ready (Gospel Friend PN-1505)

See also

- WHKW — the radio station where Wings Over Jordan started, known as WGAR from 1930 to 1990.

- Music & the Spoken Word — a similar religious radio program that has been on the air since 1929.

Documentaries

- Wings Over Jordan: We Remember (1989)