Émile Durkheim facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Émile Durkheim

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

David Émile Durkheim

15 April 1858 Épinal, France

|

| Died | 15 November 1917 (aged 59) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure Friedrich Wilhelms University University of Leipzig University of Marburg |

| Known for | Social fact Sacred–profane dichotomy Collective consciousness Social integration Anomie Collective effervescence |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Philosophy, sociology, education, anthropology, religious studies |

| Institutions | University of Paris University of Bordeaux |

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

|

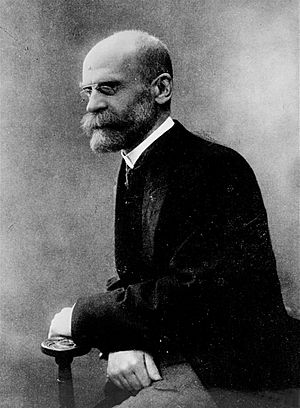

Émile Durkheim (born April 15, 1858 – died November 15, 1917) was a very important French thinker. He is known as one of the main people who helped create the study of society, called sociology. Along with Karl Marx and Max Weber, he is seen as a key person who shaped modern social science.

Durkheim spent a lot of time thinking about how societies stay together and work well in modern times. In today's world, old traditions and religious ties are not as strong as they used to be. New ways of living and new groups have also appeared. Durkheim believed that we could study society using scientific tools. He used things like statistics, surveys, and looking at history to understand how societies change.

His first big book on sociology was The Division of Labour in Society (1893). Then, in 1895, he wrote The Rules of Sociological Method. In the same year, Durkheim started the first sociology department in Europe and became France's first professor of sociology. In 1898, he started a journal called L'Année Sociologique. His book The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912) shared his ideas about religion. It compared how people lived and believed in very old societies to how they live today.

Durkheim really wanted sociology to be seen as a real science. He improved on the ideas of Auguste Comte, who believed in using science to study society. Durkheim thought that sociology should study "social facts." These are like rules or ways of acting that are part of society, not just individual people. He believed that social science should look at society as a whole, not just at what individuals do.

He was a very important thinker in France until he passed away in 1917. He gave many talks and wrote many books on different topics. These included how we gain knowledge, morality, how society is divided, religion, laws, education, and deviance (actions that go against social rules). Some of the ideas he came up with, like "collective consciousness" (shared beliefs and feelings), are still used today.

Contents

About Durkheim's Life

His Early Life and Family

David Émile Durkheim was born on April 15, 1858, in Épinal, France. He came from a long line of French Jewish rabbis. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all rabbis. Young Durkheim even started his education in a rabbinical school.

However, he soon changed schools and decided not to become a rabbi. Durkheim lived a life that was not religious. Much of his work tried to show that religious ideas came from how people interacted in society, not from divine (godly) reasons. Even so, Durkheim stayed close to his family and the Jewish community. Many of his important helpers and students were Jewish, and some were even related to him. For example, Marcel Mauss, a famous social anthropologist, was his nephew.

His Education Journey

Durkheim was a very smart student. He got into the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in 1879. This was a very bright class, and many of his classmates became famous thinkers in France. At ENS, Durkheim studied under Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, who had a scientific way of looking at society. Durkheim wrote his Latin paper on Montesquieu.

At the same time, he read books by Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. This made Durkheim interested in studying society scientifically very early in his career. This was different from the French school system at the time, which did not have social science classes. Durkheim found other subjects less interesting. He focused on ethics (the study of right and wrong) and then on sociology. He earned his degree in philosophy in 1882.

It was hard for Durkheim to get a big job in Paris because of his new ideas about society. From 1882 to 1887, he taught philosophy in smaller schools. In 1885, he went to Germany for two years. There, he studied sociology at different universities. In Leipzig, he learned to value looking at real facts and details, which was different from the more abstract French way of thinking. By 1886, he had started writing his main book, The Division of Labour in Society. He was working hard to create the new science of sociology.

Durkheim's Teaching Career

Durkheim's time in Germany led to many articles about German social science. His writings became well-known in France. In 1887, he got a teaching job at the University of Bordeaux. There, he taught the university's first social science course. He taught both pedagogy (the study of teaching) and sociology. This was a big step, showing that social sciences were becoming more important.

From this job, Durkheim helped change the French school system. He brought the study of social science into the school lessons. However, his ideas that religion and morality could be explained by how people interact in society made many people disagree with him.

In 1887, Durkheim married Louise Dreyfus. They had two children, Marie and André.

The 1890s were a very busy time for Durkheim. In 1893, he published The Division of Labour in Society. This was his main paper for his doctorate and a key book about how human society works and grows. Durkheim's interest in social phenomena (things that happen in society) was also sparked by politics. France had lost a war, and a new government was in charge. Many people wanted France to be strong again. Durkheim, who was Jewish and supported the new government, was in a political minority. This made him even more active in his ideas.

In 1895, he published The Rules of Sociological Method. This book explained what sociology is and how it should be done. He also started the first sociology department in Europe at the University of Bordeaux. In 1898, he started L'Année Sociologique, the first French social science journal. This journal helped share the work of his growing number of students and helpers.

By 1902, Durkheim finally got a top job in Paris. He became the head of education at the Sorbonne. He became a full professor in 1906, and in 1913, he was named head of "Education and Sociology." This job gave Durkheim a lot of power. His lectures were required for all students. He had a big impact on new teachers and also advised the Ministry of Education. In 1912, he published his last major book, The Elementary Forms of The Religious Life.

His Final Years

World War I had a very sad effect on Durkheim's life. He loved France, but he believed in a non-religious, logical French way of life. The war and the strong nationalistic feelings that came with it made his ideas hard to keep up. Durkheim worked to support his country in the war. But his refusal to join in simple national pride (along with his Jewish background) made him a target for some right-wing groups in France.

Even worse, many of the students Durkheim had taught were sent to fight in the war. Many of them died. In December 1915, Durkheim's own son, André, died on the war front. Durkheim never truly recovered from this loss. He was very sad and had a stroke in Paris on November 15, 1917. He was buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

How Durkheim Studied Society

In his book The Rules of Sociological Method (1895), Durkheim wanted to create a way of studying society that would make sociology truly scientific. He asked how a sociologist could study something that they are already a part of. Durkheim believed that observations should be as fair and unbiased as possible. He said that a social fact should always be studied by how it relates to other social facts, not by the person studying it. Sociology, he thought, should compare different social facts rather than just looking at single ones.

Durkheim wanted to create one of the first strict scientific ways to study social events. He was one of the first to explain why different parts of society exist and how they work together to keep society going. He also compared society to a living body, where all parts work together. This is why his work is sometimes seen as an early form of functionalism. Durkheim also believed that society was more than just the sum of its individual parts.

Unlike other thinkers of his time, he did not focus on what makes individuals act. Instead, he focused on studying social facts.

What Influenced Durkheim's Ideas

During his studies, Durkheim was influenced by two thinkers: Charles Renouvier and Émile Boutroux. From them, he learned about rationalism (using reason), studying morality scientifically, and education without religion. His way of studying was also influenced by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, who supported the scientific method.

Auguste Comte's Influence

A big influence on Durkheim was the idea of sociological positivism from Auguste Comte. Comte wanted to use the scientific method from natural sciences (like physics) to study social sciences. Comte believed that a true social science should look at real facts and find general rules from how these facts relate to each other. Durkheim agreed with Comte on many points:

- He agreed that studying society should be based on looking at facts.

- He believed that the only way to gain true knowledge was through the scientific method.

- He thought that social sciences could only become scientific if they got rid of abstract, unprovable ideas.

Realism in Society

Another influence on Durkheim's view of society was a way of thinking called social realism. This idea says that real social things exist in the world outside of us. These things are real even if we don't personally see or feel them. Durkheim used this idea to show that social realities exist on their own, separate from what any single person thinks or feels.

This idea is different from empiricism and positivism. Empiricists, like David Hume, believed that everything we know comes from our senses. So, things only exist because we perceive them. Comte's positivism went further, saying that scientific rules could be found from observations. Durkheim went even further. He said that sociology would not just find "obvious" rules, but would discover the true nature of society.

Jewish Background

Scholars have also discussed how Jewish ideas might have influenced Durkheim's work. It's not fully clear. Some say his ideas are like a non-religious form of Jewish thought. Others say it's hard to prove a direct link between Jewish thought and his achievements.

Durkheim's Main Ideas

Throughout his career, Durkheim had three main goals. First, he wanted to make sociology a new, recognized subject in universities. Second, he wanted to understand how societies could stay strong and connected in modern times. This was important because shared religion and background were no longer enough to hold people together. To do this, he wrote a lot about how laws, religion, education, and other forces affect society and how people connect. Lastly, Durkheim cared about how scientific knowledge could be used in real life.

Making Sociology a Science

Durkheim wrote some of the clearest statements about what sociology is and how it should be done. He wanted to make sociology a science. He argued that sociology was "not a helper to any other science; it is its own distinct and independent science."

To give sociology a place in universities and make sure it was a real science, it needed its own clear subject and its own way of studying things. He said that "in every society, there is a certain group of things that are different from those studied by other natural sciences."

One of sociology's main goals is to find structural "social facts." Making sociology a recognized academic subject is one of Durkheim's biggest and longest-lasting achievements. His work has greatly influenced ideas like structuralism and structural functionalism in sociology.

What are Social Facts?

Durkheim's work focused on studying social facts. He created this term to describe things that exist on their own, are not tied to what individuals do, but still have a strong influence on them. Durkheim believed that social facts have their own independent existence. They are bigger and more real than the actions of the people who make up society. Only these social facts can explain why certain things happen in society.

Because they are outside of individual people, social facts can also make people in society act in certain ways. This can be seen with formal laws and rules, but also with unwritten rules, like religious customs or family traditions. Unlike facts studied in natural sciences, a social fact is a special kind of thing. Durkheim said, "the reason for a social fact must be found among earlier social facts, not in what individuals think."

These facts have a power that can control how individuals behave. Durkheim believed that these things cannot be explained by biology or psychology. Social facts can be physical things (like objects) or non-physical things (like meanings or feelings). Even though non-physical facts cannot be seen or touched, they are real and have a strong influence. Physical objects can also represent both physical and non-physical social facts. For example, a flag is a physical social fact, but it also has many non-physical social facts attached to it, like its meaning and importance.

Many social facts, however, have no physical form. Even very "individual" or "personal" feelings, like love or freedom, were seen by Durkheim as objective social facts. So, sociology's job is to find out what these social facts are like. This can be done by using numbers and experiments. Durkheim often used statistics in his work.

Durkheim saw society itself, like other social institutions, as a collection of social facts. More than just "what society is," Durkheim wanted to know "how is a society created?" and "what holds a society together?" In The Division of Labour in Society, he tried to answer the second question.

Collective Consciousness

Durkheim thought that humans are naturally a bit selfish. But "collective consciousness" (which means shared rules, beliefs, and values) forms the moral base of society. This leads to social integration (how well people are connected). Collective consciousness is super important for society. Without it, society cannot survive. This shared consciousness creates society and keeps it together. At the same time, individuals create this collective consciousness through how they interact. Through collective consciousness, people see each other as social beings, not just animals. The emotional part of this shared consciousness helps us overcome our selfishness. Because we are emotionally tied to our culture, we act in social ways because we feel it's the right thing to do. A key part of forming society is social interaction. Durkheim believed that when people are in a group, they will naturally act in a way that forms a society.

Culture and Society's Evolution

When groups of people interact, they create their own culture and attach strong feelings to it. This makes culture another important social fact. Durkheim was one of the first thinkers to look at culture so closely. He was interested in how different cultures exist, but society still stays together. Durkheim answered that any differences in culture are overcome by a bigger, common cultural system and by law.

Durkheim described how societies change, like how living things evolve. He said societies move from "mechanical solidarity" to "organic solidarity".

- In simpler societies (mechanical solidarity), people are connected because they are similar and have personal ties and traditions. They are often self-sufficient. There is less connection, so force and punishment are used to keep society together. People also have fewer choices in life.

- In more complex societies (organic solidarity), people are much more connected and depend on each other. There is a lot of specialization and cooperation. People rely on others to do their specific jobs, which are needed for a complex society to work.

This change from mechanical to organic solidarity happens because of: 1. More people and more people living in the same area. 2. More "morality density" (more complex ways people interact). 3. More specialization in jobs.

One way these societies are different is how law works. In mechanical societies, law focuses on punishment. It tries to make the community stronger, often by making punishments public and harsh. In organic societies, law focuses on fixing the harm done and cares more about individuals than the whole community.

A main feature of modern, organic society is how important the idea of the individual becomes. The individual, not the group, becomes the focus of rights and duties. This role was once filled by religion. Durkheim saw how many people and how crowded places became as key reasons for societies to change and for modern life to appear. As more people live in an area, they interact more, and society becomes more complex. More competition between people also leads to more specialized jobs. Over time, the importance of the government, laws, and the individual grows, while religion and shared moral feelings become less important.

Durkheim also looked at fashion as an example of culture changing. He noticed that fashion often goes in cycles. He believed that fashion helps show the difference between lower classes and upper classes. But because lower classes want to look like upper classes, they will eventually copy the upper-class fashion. This makes the upper class adopt a new fashion to stay different.

Understanding Religion

In The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912), Durkheim first wanted to find out where religion came from in society and what its purpose was. He felt that religion created friendship and unity among people. His second goal was to find links between different religions in different cultures. He wanted to find what all religions had in common, beyond ideas of spirituality and God.

Durkheim's definition of religion did not mention anything supernatural or God. He disagreed with earlier definitions that said religion was just "belief in supernatural beings." He found that very old societies, like the Aboriginal Australians, did not divide reality into "natural" versus "supernatural." Instead, they divided it into "sacred" (holy) and "profane" (everyday) things. These were not about good or evil, as both could include good or bad things. Durkheim said religion involves three main things:

- The sacred: Ideas and feelings that create awe and respect, often inspired by society itself.

- The beliefs & practices: Actions that create a strong emotional state of collective effervescence (a shared feeling of excitement), making symbols important and holy.

- The moral community: A group of people who share the same ideas about right and wrong.

Durkheim saw religion as the most basic social institution for humans. He believed it gave rise to other social forms. Religion gave humanity the strongest sense of collective consciousness (shared beliefs). Durkheim saw religion as something that appeared in early hunter and gatherer societies. As groups grew, strong emotions and shared excitement made them act in new ways, giving them a feeling of some hidden force guiding them. Over time, as emotions became symbols and interactions became rituals, religion became more organized. This led to the division between the sacred and the profane.

However, Durkheim also thought that religion was becoming less important. He believed it was slowly being replaced by science and the focus on the individual. But even if religion was losing its importance, Durkheim argued it still laid the foundation for modern society and how people interact. He doubted modern times, seeing them as "a period of change and average morality."

Durkheim also argued that our main ways of understanding the world come from religion. He wrote that religion gave rise to most, if not all, other social ideas. Durkheim believed that our ways of thinking are created by society, and so they are shared creations. As people create societies, they also create these ways of thinking, but they do so without realizing it. These ideas exist before any individual's experience. For example, our idea of time is defined by how we measure it with a calendar. Calendars were created to help us keep track of social gatherings and rituals, which came from religion. In the end, even science, which seems very logical, can trace its beginnings to religion. Durkheim stated, "Religion gave birth to all that is essential in the society."

In his work, Durkheim focused on totemism, the religion of the Aboriginal Australians and Native Americans. Durkheim saw this as the oldest religion. He focused on it because he believed its simplicity would make it easier to discuss the basic parts of religion.

Durkheim's Impact and Legacy

Durkheim had a big impact on how anthropology and sociology grew as subjects. Making sociology a recognized academic subject is one of his biggest and most lasting achievements. In sociology, his work has greatly influenced ideas like structuralism and structural functionalism.

Many scholars have been inspired by Durkheim, including Marcel Mauss, Maurice Halbwachs, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, Talcott Parsons, Robert K. Merton, Jean Piaget, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Michel Foucault, and others.

More recently, Durkheim has influenced sociologists like Steven Lukes, Robert N. Bellah, and Pierre Bourdieu. His idea of collective consciousness also greatly influenced the Turkish nationalism of Ziya Gökalp, who is seen as the founder of Turkish sociology.

Outside of sociology, Durkheim has influenced philosophers like Henri Bergson and Emmanuel Levinas. His ideas can also be seen in the work of some structuralist thinkers from the 1960s, even if they don't directly mention him.

Selected Works

- The Division of Labour in Society (1893)

- The Rules of Sociological Method (1895)

- On the Normality of Crime (1895)

- Primitive Classification (1903), with Marcel Mauss

- The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)

Published after his death

- Education and Sociology (1922)

- Sociology and Philosophy (1924)

- Moral Education (1925)

- Socialism (1928)

See also

In Spanish: Émile Durkheim para niños

In Spanish: Émile Durkheim para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |