1795–1820 in Western fashion facts for kids

Fashion changed a lot in Europe and countries influenced by Europe between 1795 and 1820. Fancy styles with brocades, lace, wigs, and powder from the earlier 1700s disappeared. After the French Revolution, people didn't want to look like French nobles. Clothes became more about showing who you were as a person, not just your social status. This meant that fashion changes around 1800 allowed people to show new public identities and even hint at their private selves. Fashion became a way to show new social values and was a key part of the changes happening.

For women, everyday clothes like skirts and jackets were practical. Women's fashion was inspired by ancient Greek and Roman styles. Stiff corsets were replaced with softer ones. This new style showed off the natural body shape.

This time in British history is called the Regency period. It was when George IV ruled as Prince Regent because his father, George III, was ill. This period, in terms of fashion, architecture, and culture, started with the French Revolution in 1789 and ended when Queen Victoria became queen in 1837. Many famous people lived during this time, like Napoleon and Josephine, Juliette Récamier, Jane Austen, Lord Byron, and Beau Brummell. Beau Brummell was a fashion leader for men. He made trousers, perfect tailoring, and clean, simple linen popular.

In Germany, cities that were republics stopped wearing their traditional, simple clothes. They started to follow French and English fashion, like short-sleeved chemise dresses and Spencer jackets. American fashion copied French styles but made them simpler, using shawls and tunics to make sheer dresses less see-through. However, Spanish majos (people who dressed in traditional Spanish style) went against the fancy French Enlightenment ideas. They made traditional Spanish clothes even more elaborate.

By the late 1700s, fashion was changing not just in style, but also in how people thought about themselves and society. Before this, your identity was thought to change with your clothes. But by the 1780s, a new "natural" style allowed your true self to show through your clothes.

In the 1790s, people started thinking about an "inner self" and an "outer self." Before this, clothing was the main way to show who you were. For example, at a masquerade ball, people wore specific costumes, so they couldn't show their own personality through their clothes. The new "natural" style focused on clothes being easy and comfortable. People also cared more about hygiene, and clothes became lighter, easier to change, and wash often. Even upper-class women started wearing shorter dresses instead of long, restrictive ones. This led to new trims and details on skirts becoming popular again. During the Regency years, fancy historical and Eastern-inspired details were added. These details showed off wealth because they took a lot of work to make. This was especially true for skirts, which had many decorations and trims.

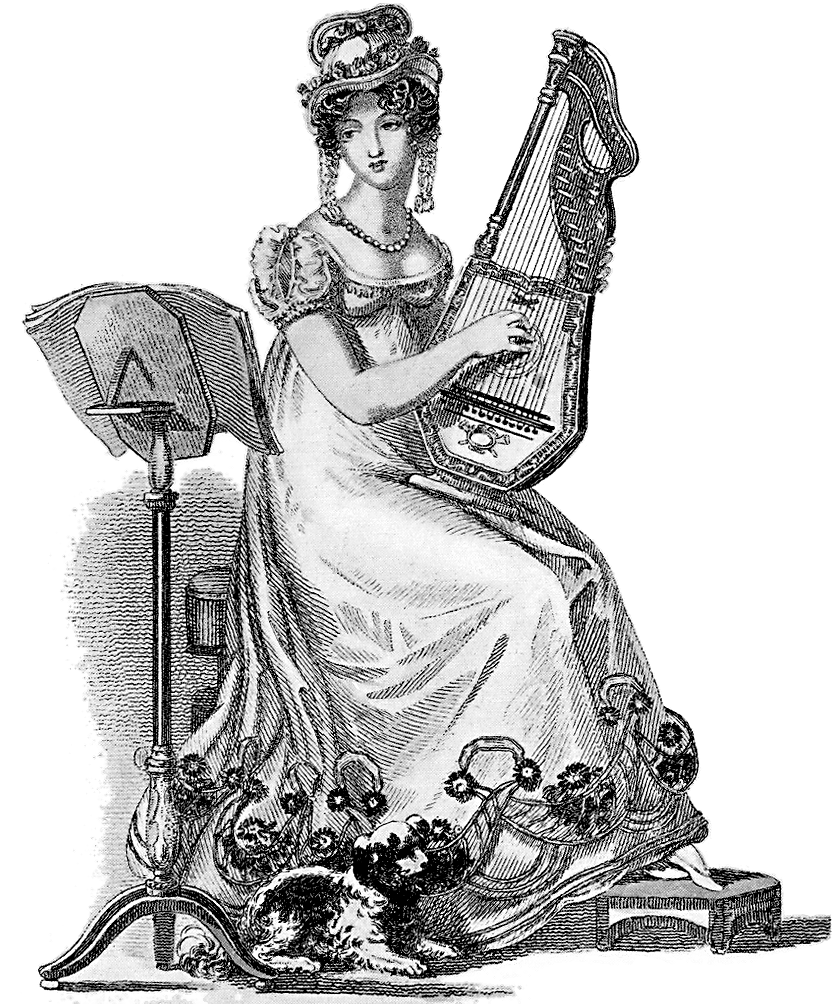

Women's fashion was also influenced by men's styles, like tailored waistcoats and jackets. This move towards practical clothes meant that fashion was less about showing class or gender. Instead, clothes were meant to fit a person's daily life. This was also when fashion magazines and journals became very popular. They were usually monthly magazines that helped people keep up with the latest styles.

Contents

- How the Industrial Revolution Changed Fashion

- Fashion Changes Over Time

- Women's Fashion

- Men's Fashion

- Children's Fashion

- How Directoire, Empire, and Regency Fashions Were Seen Later

- See Also

How the Industrial Revolution Changed Fashion

In the late 1700s, clothes were mostly sold by individual shopkeepers who also made the items. Customers usually lived nearby, and shops became popular through word-of-mouth. This was different from large warehouses that sold goods not made in their own shop. But things started to change around 1800. People wanted clothes to be made faster and to have more choices. Because of the Industrial Revolution, better transportation and new machines helped fashion change even more quickly.

The first sewing machine appeared in 1790. Later, Josef Madersperger started working on his sewing machine in 1807 and showed his first working model in 1814. Sewing machines made clothing production faster. However, they didn't have a big impact until the 1840s. Before 1820, all clothing was still made by hand. Meanwhile, new ways of spinning, weaving, and printing cotton developed in the 1700s. These made washable fabrics cheaper and widely available. These strong and affordable fabrics became popular with more people. Machines helped these techniques develop even further. Before, accessories like embroidery and lace were made in small amounts by skilled craftspeople and sold in their shops. In 1804, John Duncan built a machine for embroidering. This meant these important accessories could be made in factories and sent to shops all over the country. These new technologies in clothing making allowed for many more styles. Fashion could also change very quickly.

The Industrial Revolution also made travel easier between Europe and America. When Louis Simond first visited America, he was amazed by how much people traveled. He wrote that almost everyone had visited London at least once. New canals and railways not only moved people but also created bigger markets. They transported factory-made goods over long distances. The growth of industry across the Western world increased clothing production. People were encouraged to travel more and buy more goods than ever before.

Communication also got better during this time. New fashion ideas were shared through small dolls dressed in the latest styles, newspapers, and illustrated magazines. For example, La Belle Assemblée, started by John Bell, was a British women's magazine published from 1806 to 1837. It was famous for its fashion plates, which showed women how to dress and put together outfits.

Fashion Changes Over Time

1790s Fashion

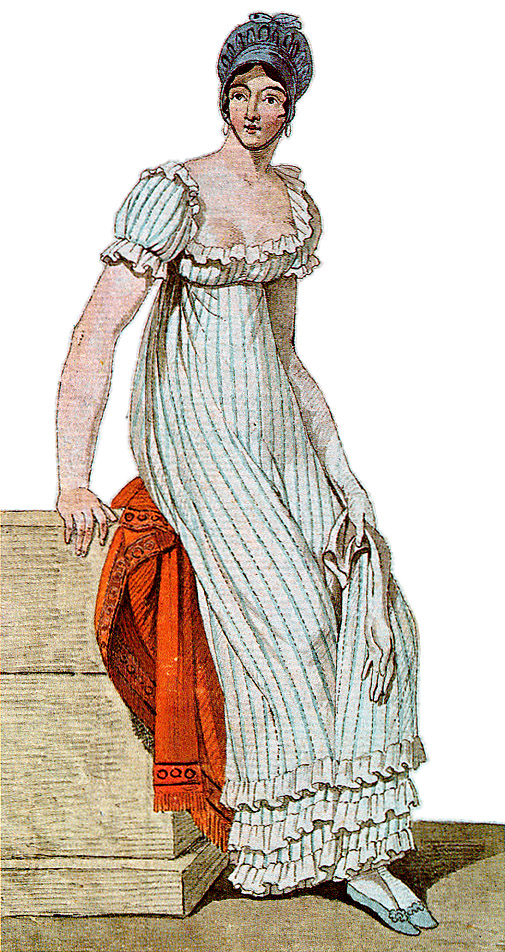

- Women: This was the "age of undress." Women dressed like statues coming to life. Greek fashion inspired styles, with high-waisted clothes and a more triangular hem. Pastel fabrics, natural makeup, and bare arms were popular. Blonde wigs were sometimes worn. Accessories included hats, turbans, gloves, jewelry, small handbags called reticules, shawls, handkerchiefs, parasols, and fans. Spanish Maja women wore layered skirts.

- Men: Trousers with perfect tailoring and linen shirts were in style. Coats were cut away in the front with long tails. Cloaks and hats were also worn. The "Dandy" style became popular. Spanish Majo men wore short jackets.

1800s Fashion

- Women: Short hair was common. White hats with trim, feathers, and lace were popular. Egyptian and Eastern influences appeared in jewelry and clothes. Shawls and hooded overcoats were worn. Hair was often in masses of curls, sometimes pulled back into a bun.

- Men: Linen shirts with high collars and tall hats were fashionable. Hair was short and without wigs, often in styles like à la Titus or Bedford Crop, but sometimes with long locks.

1810s Fashion

- Women: Soft, sheer, classical drapes were popular. High-waisted dresses had a raised back waist. Short, fitted, single-breasted jackets were worn. There were specific dresses for morning, walking, and evening, as well as riding habits. Bare bosoms and arms were common. Hair was parted in the center, with tight ringlets over the ears.

- Men: Fitted, single-breasted tailcoats were worn. Cravats were wrapped high up to the chin. Sideburns and "Brutus style" natural hair were popular. Tight breeches and silk stockings were common. Accessories included gold watches, canes, and hats when outdoors.

1820s Fashion

- Women: Dress waistlines started to drop. Hems and necklines had elaborate decorations. Skirts became cone-shaped. Sleeves were pinched.

- Men: Overcoats or greatcoats with fur or velvet collars were fashionable. The Garrick coat was popular. Wellington boots and jockey boots were worn.

Women's Fashion

Overview of Women's Styles

In this period, fashionable women's clothes had a high waistline, just under the bust. This style is now called the Empire silhouette. Dresses were fitted closely to the upper body and then fell loosely below. These styles are also known as "Directoire style" (from the French government in the late 1790s) or "Empire style" (from Napoleon's time). The term "Regency" is also used for this period. The names "Empire silhouette" and "Directoire style" were not used when these clothes were actually worn.

These fashions from 1795–1820 were very different from earlier and later styles. In the 1700s and most of the 1800s, women's clothes were tight around the waist and had very full skirts, often made bigger with hoop skirts or crinolines. Around 1800, women's fashion started to follow classical ideas. It was inspired by ancient Greek and Roman styles, with graceful, loosely flowing dresses gathered or accented under the bust. Stiff corsets were replaced with a focus on the natural body shape. Bodices were short, with waistlines just below the bust. Fabrics like light muslin were popular because they were sheer and draped well. Heavier printed cottons and wools were also worn.

Gowns and Dresses

Inspired by ancient styles, "undress" was the popular look. This meant casual and informal. It was the type of gown a woman wore from morning until noon or later, depending on her plans. These short-waisted dresses had soft, loose skirts. They were often made of white, almost see-through muslin. Muslin was easy to wash and draped loosely, like the clothes on Greek and Roman statues. Satin was sometimes used for evening wear. "Half Dress" was for going out during the day or meeting guests. "Full Dress" was for formal events, day or night. "Evening Dress" was only for evening parties. So, from 1795 to 1820, many middle- and upper-class women could wear comfortable, less restrictive clothes and still be fashionable.

Middle- and upper-class women usually had different clothes for morning and evening. Both men and women changed clothes for the evening meal and any entertainment. There were also specific clothes for afternoon, walking, riding, traveling, and dinner.

In a fashion guide from London in 1811, called Mirror of Graces, it said:

In the morning the arms and bosom must be completely covered to the throat and wrists. From the dinner-hour to the termination of the day, the arms, to a graceful height above the elbow, may be bare; and the neck and shoulders unveiled as far as delicacy will allow.

- Mourning dresses were worn to show sadness for a loved one. They had high necks and long sleeves, covering the throat and wrists. They were usually plain black and had no decorations.

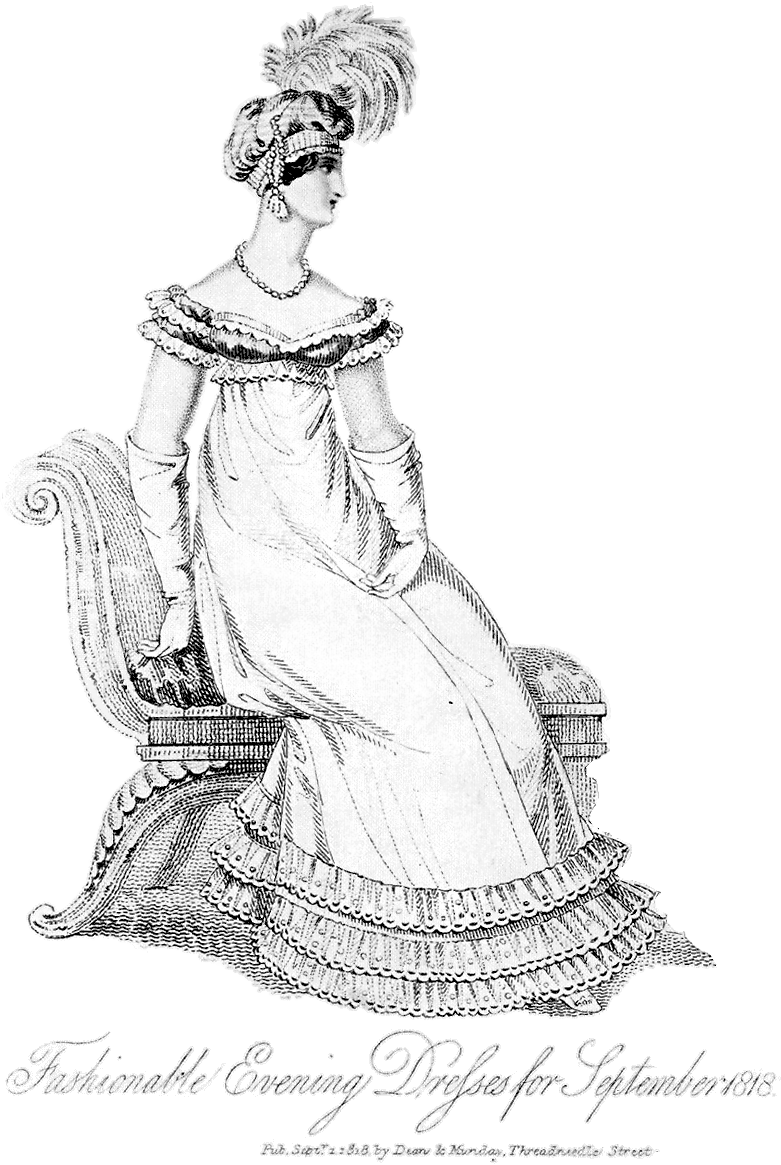

- Formal gowns were often very decorated with lace, ribbons, and netting. They had low necklines and short sleeves, showing the chest. Bare arms were covered by long white gloves. However, the guide warned young women not to show too much of their chest.

The guide also suggested that young ladies wear softer colors like pink, periwinkle blue, or lilac. Older women could wear bolder colors like purple, black, crimson, deep blue, or yellow.

Many women at the time noted that being "fully dressed" meant showing the chest and shoulders. But being "under-dressed" meant having a neckline that went right up to the chin.

The Empire Silhouette

Social status was very important during the Regency era, and fashion showed this. A person's position depended on their wealth, manners, family, intelligence, and beauty. Women often relied on their husbands financially and socially. The main social activities for women were gatherings and parties, especially evening parties. These events helped build relationships. Different events required different outfits, so afternoon dresses, evening dresses, ball dresses, and other types were popular.

Women's fashion changed a lot during the Regency era. The Empire silhouette became popular. It had a fitted top and a high waist. This "new natural style" showed off the body's natural lines. Clothes became lighter and easier to care for. Women often wore several layers: undergarments, gowns, and outerwear. The chemise, a thin undergarment, prevented the sheer dresses from being too transparent. Outerwear like the spencer jacket and the pelisse coat were also popular.

The Empire silhouette was created around the late 1700s and early 1800s, during the First French Empire. It was linked to France's love for Greek styles. However, its history is more complex. It was first worn by the French queen, who was inspired by Caribbean, not Greek, fashion. The style was often worn in white to show high social status. Josephine Bonaparte was a key figure for the Empire waistline, with her fancy and decorated Empire line dresses. Regency women followed the Empire style and its raised waistlines, even when their countries were at war. From the 1780s and early 1790s, women's clothes became slimmer, and waistlines moved up. After 1795, waistlines rose dramatically, and skirts became narrower. A few years later, England and France both focused on the high-waisted style, leading to the Empire style.

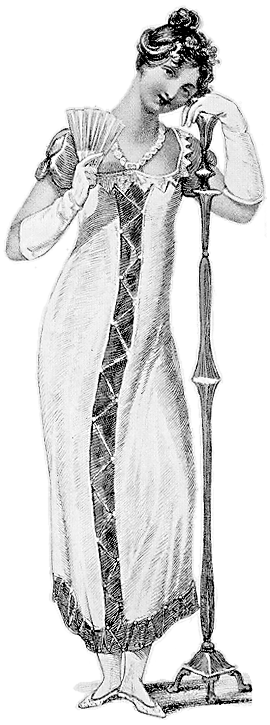

This style started as part of Neoclassical fashion. It brought back looks from Greco-Roman art, which showed women wearing loose, rectangular tunics called peplos. These were belted under the bust, giving support and a cool, comfortable outfit, especially in warm weather. The Empire silhouette was defined by the waistline, placed right under the bust. It was the main style for women's clothing during the Regency era. The dresses were usually light, long, and loose-fitting. They were often white and sheer from the ankle to just below the bodice. A long, rectangular shawl or wrap, often plain red with a decorated border, helped in colder weather. Dresses had a fitted bodice, creating a high-waisted look.

This style had been popular on and off for hundreds of years. The shape of the dresses also made the body look longer. The clothing could also be draped to make the bust look bigger. Lightweight fabrics were used to create a flowing effect. Ribbons, sashes, and other decorations highlighted the waistline. Empire gowns often had a low neckline and short sleeves and were worn for formal events. Day dresses, however, had higher necklines and long sleeves. The chemisette was a common item for fashionable ladies. Even with these differences, the high waistline remained the same.

Hairstyles and Hats

During this time, the classical influence also affected hairstyles. Often, women wore many curls over their forehead and ears. Longer hair at the back was pulled up into loose buns or Psyche knots, inspired by Greek and Roman styles. By the late 1810s, front hair was parted in the middle and worn in tight ringlets over the ears. Brave women like Lady Caroline Lamb wore short, cropped hairstyles called "à la Titus". A Paris newspaper reported in 1802 that "more than half of elegant women were wearing their hair or wig à la Titus", which was a layered cut often with some hair hanging down.

In the Mirror of Graces, a Lady of Distinction wrote:

Now, easy tresses, the shining braid, the flowing ringlet confined by the antique comb, or bodkin, give graceful specimens of the simple taste of modern beauty. Nothing can correspond more elegantly with the untrammeled drapery of our newly-adopted classic raiment than this undecorated coiffure of nature.

Traditional married women still wore linen mob caps. These caps now had wider brims on the sides to cover the ears. Fashionable women wore similar caps for morning wear at home.

For the first time in centuries, respectable but daringly fashionable women would leave the house without a hat or bonnet. However, most women still wore something on their head outdoors. They were starting to stop wearing hats indoors during the day and for evening events. Popular headwear included the antique head-dress, the Queen Mary coif, Chinese hats, Oriental-inspired turbans, and Highland helmets. Bonnets were decorated with increasingly fancy ornaments like feathers and ribbons. Ladies often changed their hat decorations, replacing old trims with new ones.

Undergarments

Fashionable women of the Regency era wore several layers of undergarments. The first layer was the chemise, or shift. This was a thin garment made of white cotton, with tight, short sleeves and a low neckline if worn under evening wear. It had a plain hem that was shorter than the dress. These shifts protected the outer clothes from sweat and were washed more often. Washerwomen used strong soap and boiling water for these garments, which is why they had no color, lace, or decorations that would fade or get damaged. Chemises also helped prevent the transparent muslin or silk dresses from being too revealing.

The next layer was a pair of stays or a corset, which had fewer bones than older corsets. While very slender women might not need a corset with high-waisted classical fashions, most women still wore some kind of bust support. The goal was to look as if they weren't wearing one. The idea that corsets disappeared during the Regency period is often exaggerated. Some garments were designed to work like modern bras. "Short stays" (corsets that only went a short distance below the breasts) were often worn over the chemise. "Long stays" (corsets that went down towards the natural waist) were worn by women who wanted to look slimmer or needed more support. English women wore these more than French women. Even these long stays were not meant to squeeze the waist tightly, like Victorian corsets did.

The final layer was the petticoat. This was any skirt worn under the gown. It could be a skirt with a top part, a skirt tied over the torso, or a separate skirt. These petticoats were often worn between the underwear and the outer dress and were considered part of the outer clothing, not underwear. The bottom edge of the petticoat was meant to be seen. Women often lifted their outer dresses to protect the delicate fabric from mud or dampness, showing the coarser and cheaper petticoat. Because they were often seen, petticoats were decorated at the hem with tucks, lace, or ruffles.

"Drawers" (large, flowy 'shorts' with buttons) were only sometimes worn. Many women did not wear underwear under their dresses.

Stockings (hosiery), made of silk or knitted cotton, were held up by garters below the knee. They were usually white or a pale skin color. Suspenders for stockings were not introduced until the late 1800s.

Outerwear and Shoes

During this time, women's clothing was much thinner than in the 1700s. So, warmer outerwear became important, especially in colder places. Coat-like garments such as pelisses and redingotes were popular. Shawls, mantles, mantelets, capes, and cloaks were also worn. The mantelet was a short cape that later became longer and turned into a shawl. The redingote was a full-length coat that looked like a man's riding coat. It could be made from different fabrics and patterns. Throughout this period, the Indian shawl was the favorite wrap. Houses, especially typical English country houses, were often drafty. The sheer muslin and light silk dresses popular at the time didn't offer much warmth. Shawls were made of soft cashmere, silk, or even muslin for summer. Paisley patterns were very popular.

Short, high-waisted jackets called spencers were worn outdoors. Long-hooded cloaks, Turkish wraps, mantles, capes, Roman tunics, chemisettes, and overcoats called pelisses (which were often sleeveless and reached the ankles) were also popular. These outer garments were often made of fine fabrics like double sarsnet, Merino wool, or velvets. They were trimmed with furs like swan's down, fox, chinchilla, or sable. On May 6, 1801, Jane Austen wrote to her sister, "Black gauze cloaks are worn as much as anything."

Thin, flat fabric (silk or velvet) or leather slippers were generally worn. This was a change from the high-heeled shoes common in the 1700s.

Metal pattens were strapped onto shoes to protect them from rain or mud. They raised the feet about an inch off the ground.

Accessories

Gloves were always worn by women when outside the house. When worn inside, like during a social visit or at a ball, they were removed for dining. About glove length, A Lady of Distinction wrote:

If the prevailing fashion be to reject the long sleeve, and to partially display the arm, let the glove advance considerably above the elbow, and there be fastened with a draw-string or armlet. But this should only be the case when the arm is muscular, coarse, or scraggy. When it is fair, smooth, and round, it will admit of the glove being pushed down to a little above the wrists.

Longer gloves were worn somewhat loosely during this period, bunching up below the elbow. As described, "garters" could fasten longer gloves.

Reticules were small handbags that held personal items, like vinaigrettes. The close-fitting dresses of the time had no pockets, so these small drawstring bags were essential. These handbags were also called buskins or balantines. They were rectangular and hung from a woven band attached to a belt worn above the waist.

Parasols (as shown in the image) protected a lady's skin from the sun. They were an important fashion accessory. They were slender and light, coming in various shapes, colors, and sizes.

Fashionable ladies (and gentlemen) used fans to cool themselves. Fans also helped them express themselves through gestures and body language. Made of paper or silk on ivory or wood sticks, and printed with Eastern designs or popular scenes, these common accessories came in many shapes and styles, like pleated or rigid.

Directoire Style (1795–1799)

By the mid-1790s, neoclassical clothing became popular in France. Several things led to this simpler style for women's clothes. English women's practical outdoor wear influenced French high fashion. Also, in revolutionary France, there was a reaction against the stiff corsets and bright, heavy fabrics of the old regime (see 1750–1795 in fashion). Most importantly, Neo-classicism was adopted because it was linked to classical republican ideas, especially from Greece. This new interest in the classical past was boosted by recent discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Besides the discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum, other factors helped make neoclassical dress popular. In the early 1790s, Emma Hamilton started her "attitudes" performances, which were new at the time. These "attitudes" were loosely based on ancient pantomime, but Emma's performances didn't use masks or music. Her shows blended art and nature, making her body a form of art. To help her portray tragic mythological and historical figures, Emma wore á la grecque clothing. This style later became popular in France. She wore a simple, light-colored chemise made of thin, flowing material, gathered with a narrow ribbon under the breasts. Simple cashmere shawls were used as head coverings or to add fullness to the chemise's drape. They also helped keep the lines smooth during her performance, connecting her outstretched arms to her body and making movements fluid. Sometimes, a cape or cloak was worn to highlight the body's lines in certain poses. This emphasized the continuous flow of lines and forms in her body, showing unity and simple, continuous movement. Her hair was worn naturally, loose, and flowing. All these elements combined to create a play of light and shadow, revealing and accenting parts of the body while covering others. Emma was very skilled, and her dress style spread from Naples to Paris as wealthy Parisians took the Grand Tour.

There's also some evidence that the white muslin shift dress became popular after Thermidor because of prison clothes. Revolutionary women like Madame Tallien wore this style because it was the only clothing they had in prison. The chemise á la grecque also represented the struggle for self-expression and a rejection of old cultural values. Also, the simpler clothes worn by preteen girls in the 1780s (who no longer had to wear tiny versions of adult corsets and panniers) probably paved the way for simpler clothes for teenage girls and adult women in the 1790s. Waistlines became somewhat high by 1795, but skirts were still quite full, and neoclassical influences weren't yet dominant.

It was in the second half of the 1790s that fashionable women in France started to fully adopt a Classical style. This was based on an idealized version of ancient Greek and Roman dress, with narrow, clinging skirts. Some extreme Parisian versions of the neoclassical style, like narrow straps that bared the shoulders and sheer dresses without enough undergarments, weren't widely adopted elsewhere. However, many features of the late-1790s neoclassical style were very influential, appearing in modified forms in European fashions for the next two decades.

White was considered the best color for neoclassical clothing. Accessories were often in contrasting colors. Short trains trailing behind were common on dresses in the late 1790s.

Directoire Gallery

of the Frankland sisters by John Hoppner shows the styles of 1795.

of the Frankland sisters by John Hoppner shows the styles of 1795. by William Blake. This painting, made in 1795, shows a similar idealized ancient style. It also hints at future high fashions of the late 1790s. It is at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

by William Blake. This painting, made in 1795, shows a similar idealized ancient style. It also hints at future high fashions of the late 1790s. It is at the Fitzwilliam Museum. shows a woman and girl wearing simple, high-waisted styles from 1796.

shows a woman and girl wearing simple, high-waisted styles from 1796. of Gabrielle Josephine du Pont.

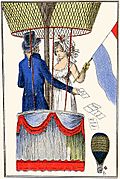

of Gabrielle Josephine du Pont. shows a lady in a low-cut, thin Directoire dress, seemingly not dressed warmly for a balloon trip.

shows a lady in a low-cut, thin Directoire dress, seemingly not dressed warmly for a balloon trip. of a white Directoire dress worn with a bright red shawl that has a Greek key border.

of a white Directoire dress worn with a bright red shawl that has a Greek key border. of a day outfit with a short "spencer" jacket. It follows the empire silhouette but is less neoclassical.

of a day outfit with a short "spencer" jacket. It follows the empire silhouette but is less neoclassical. wears an almost transparent white dress.

wears an almost transparent white dress.wears a white transparent dress over a white petticoat.

from 1799. The habit on the right has a short jacket with tails. The green habit on the left might be a redingote (a type of coat) instead of a jacket and skirt.

from 1799. The habit on the right has a short jacket with tails. The green habit on the left might be a redingote (a type of coat) instead of a jacket and skirt.

Caricatures of Directoire Style

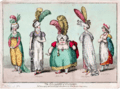

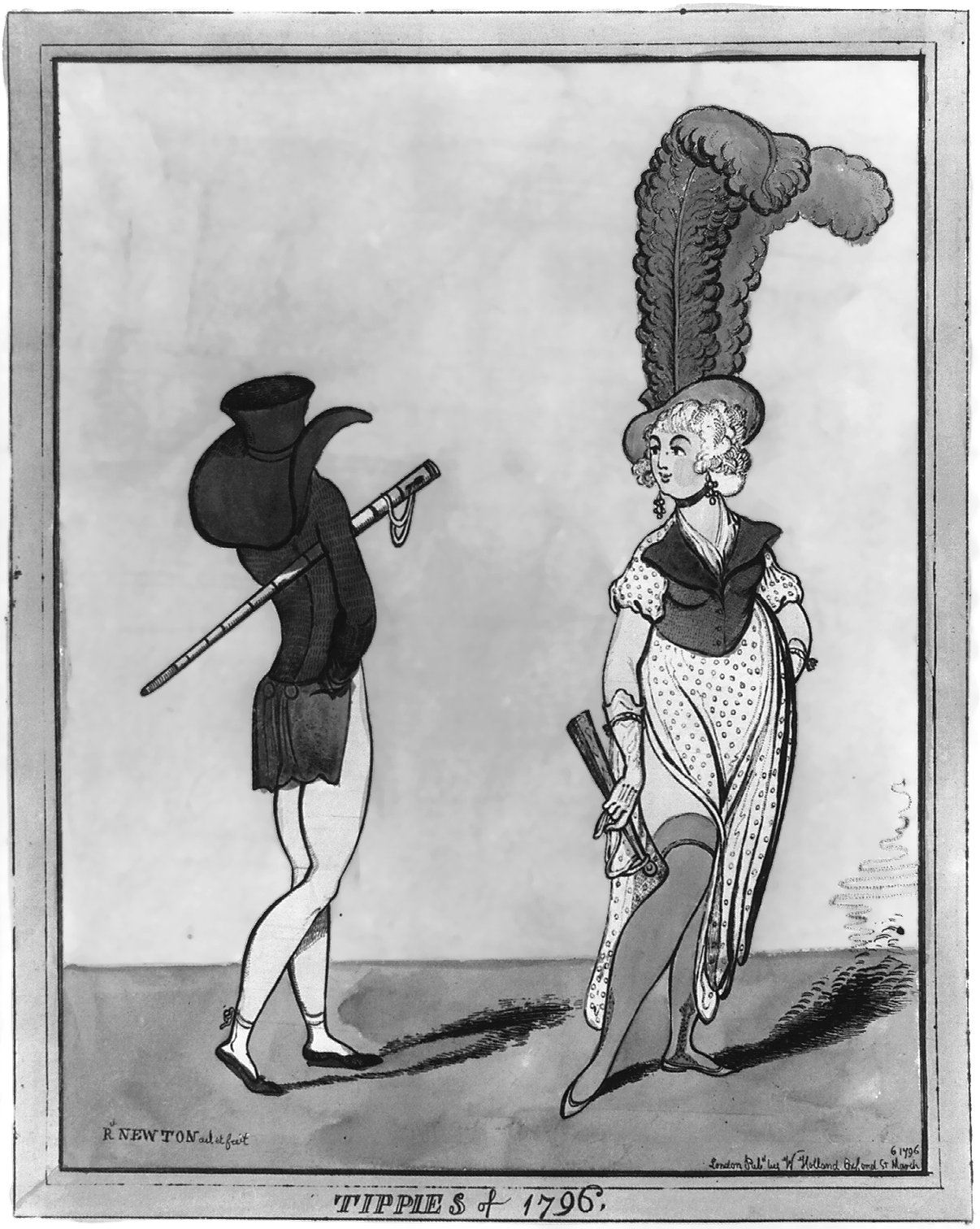

- is a caricature from 1796 by Isaac Cruikshank. It makes fun of how revealing 1796 fashions were compared to older styles. Notice the single feather on the 1796 woman's hair.

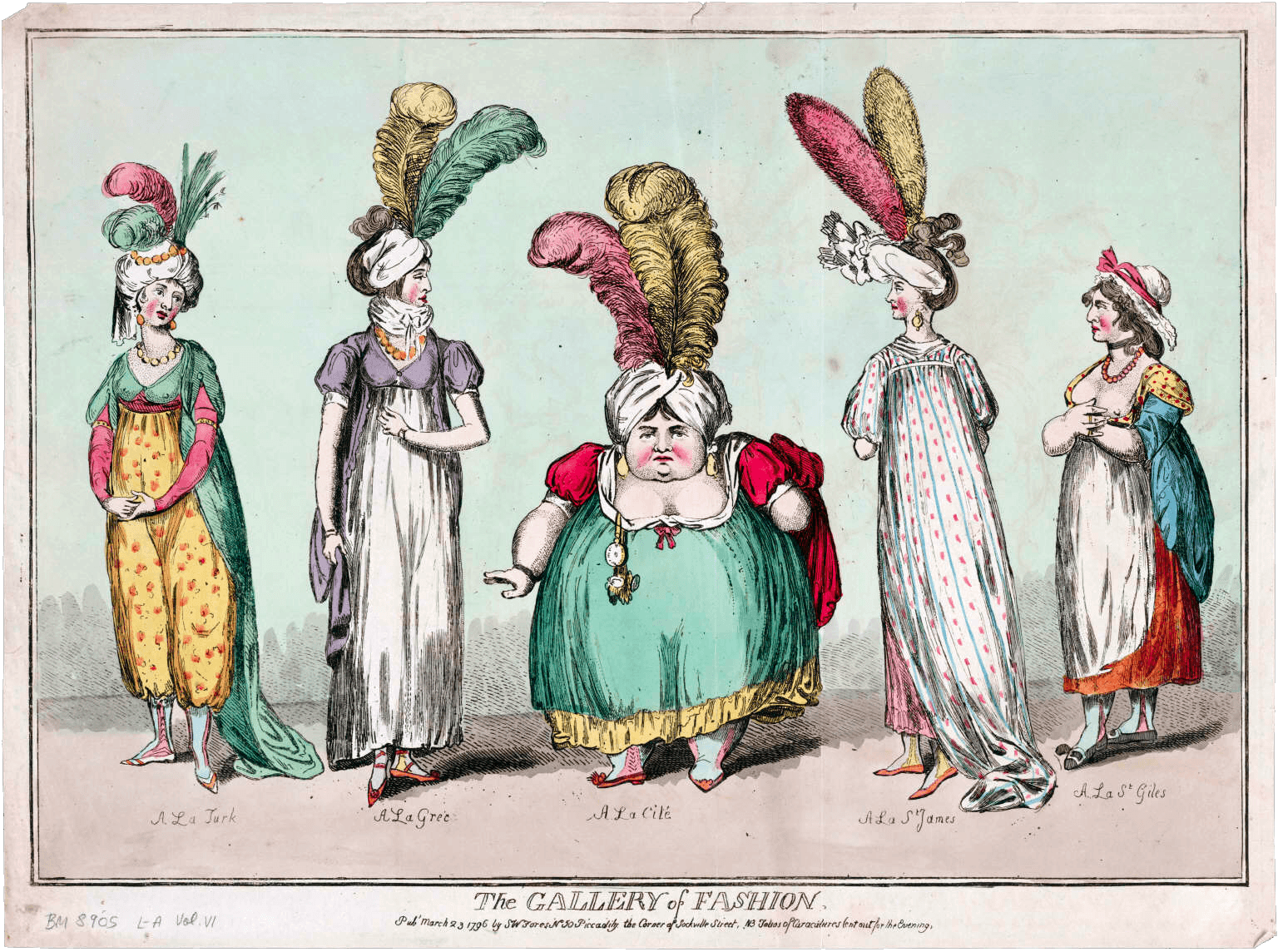

is a funny drawing that exaggerates women's feather headdresses and men's tight trousers.

is a funny drawing that exaggerates women's feather headdresses and men's tight trousers. makes fun of early neoclassical fashions.

makes fun of early neoclassical fashions.- is an exaggerated drawing by Isaac Cruikshank. It shows how sheer Parisian styles were in the late 1790s.

- "A French Invasion on the Fashionable Dress of 1798" is a British caricature. It also shows tight trousers, wigs, and square necklines.

.

.

Empire Style (1800–1815)

During the first two decades of the 1800s, fashions continued to follow the basic high-waisted empire silhouette. However, the classical influences became less strong. Dresses remained narrow in the front, but extra fabric at the raised back waist allowed for easier walking. Colors other than white became popular. The trend for sheer outer fabrics faded, except for some formal occasions. More obvious decorations started to appear on dresses, unlike the simple or subtle white-on-white embroidery of around 1800.

Empire Gallery

wears a light-pink dress with short sleeves and a high waistline in 1804. She also has a thin necklace, a golden shawl, and her hair in a bun with loose waves. Her outfit is simple yet elegant, typical of the time.

wears a light-pink dress with short sleeves and a high waistline in 1804. She also has a thin necklace, a golden shawl, and her hair in a bun with loose waves. Her outfit is simple yet elegant, typical of the time. by Marguerite Gérard shows two different dresses, one more detailed than the other. Notice the low neckline that was fashionable then.

by Marguerite Gérard shows two different dresses, one more detailed than the other. Notice the low neckline that was fashionable then.- from 1804. Notice the even lower neckline.

from around 1805. It is pleated in the front and has a narrow ruffled brim that widens to cover the ears. From America.

from around 1805. It is pleated in the front and has a narrow ruffled brim that widens to cover the ears. From America. from around 1806.

from around 1806. wears a dress with a sheer top layer over a partial lining and a patterned shawl. She has a gold armlet on her left arm. Her hair is styled in loose waves around her temples and ears. From Massachusetts, 1809.

wears a dress with a sheer top layer over a partial lining and a patterned shawl. She has a gold armlet on her left arm. Her hair is styled in loose waves around her temples and ears. From Massachusetts, 1809. worn with elbow-length gloves.

worn with elbow-length gloves. , shown with elbow-length gloves.

, shown with elbow-length gloves. of a woman in a "Schute" bonnet and a blue-striped dress with ruffles.

of a woman in a "Schute" bonnet and a blue-striped dress with ruffles. of a woman by Henri Mulard, around 1810.

of a woman by Henri Mulard, around 1810. of a panniered English court gown, 1810.

of a panniered English court gown, 1810.wears a simple white satin gown and a common shawl. Her headdress is decorated with ostrich feathers.

Caricatures of Empire Style

is a caricature from 1807. It claims to show how revealing 1807 fashions were compared to the 1700s, exaggerating the difference.

is a caricature from 1807. It claims to show how revealing 1807 fashions were compared to the 1700s, exaggerating the difference. is an 1810 caricature by Gillray. It makes fun of clinging dresses worn with few petticoats.

is an 1810 caricature by Gillray. It makes fun of clinging dresses worn with few petticoats. is an 1810 caricature of impractical hat styles.

is an 1810 caricature of impractical hat styles. is an 1813 caricature by George Cruikshank.

is an 1813 caricature by George Cruikshank.

Regency Style (1815–1820) Gallery

This era marked the end of any remaining neoclassical or Greek-inspired styles in women's clothing. This was especially clear in France because Emperor Napoleon stopped trade in the fabrics used for neoclassical dresses. While waistlines were still high, they started to drop slightly. Larger and more decorations, especially near the hem and neckline, hinted at even fancier styles to come. More petticoats were worn, and skirts became stiffer and more cone-shaped. Stiffness could be added with layers of ruffles and tucks on a hem, or with corded or ruffled petticoats. Sleeves started to be pulled, tied, and pinched in ways that were more influenced by romantic and gothic styles than classical ones. Hats and hairstyles became more elaborate and decorated, growing taller to balance the widening skirts.

.

. .

. and her daughter have their hair parted in the front center with tight ringlets over each ear. The back hair is brushed into a bun. From 1816.

and her daughter have their hair parted in the front center with tight ringlets over each ear. The back hair is brushed into a bun. From 1816.wears a red dress over a white chemise in 1816.

, showing the start of the trend towards a cone-shaped silhouette.

, showing the start of the trend towards a cone-shaped silhouette. that is heavily trimmed and tasseled.

that is heavily trimmed and tasseled. .

. wears the new fashion for rich colors. Her crimson gown has ruffles at the neck and sleeves. She wears it with an ivory shawl that has a wide paisley-patterned border, 1818.

wears the new fashion for rich colors. Her crimson gown has ruffles at the neck and sleeves. She wears it with an ivory shawl that has a wide paisley-patterned border, 1818. .

. , with decorations near the hem.

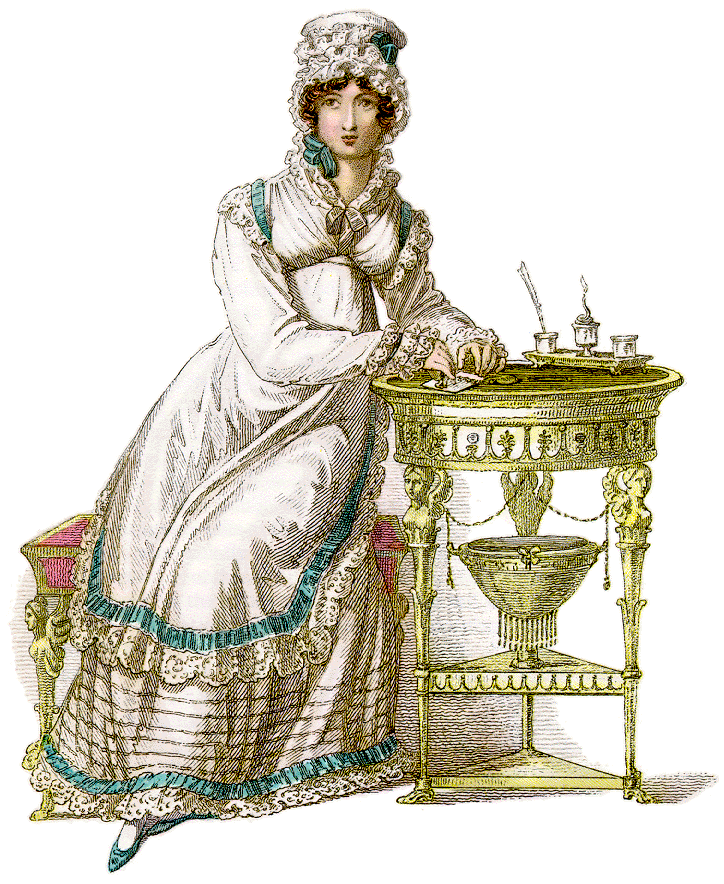

, with decorations near the hem. (for staying inside the house during mornings and early afternoons), 1819.

(for staying inside the house during mornings and early afternoons), 1819.

Caricature of Regency Style

is a funny drawing by George Cruikshank. It makes fun of the female trend towards cone-shaped skirts and male high cravats and dandyism.

is a funny drawing by George Cruikshank. It makes fun of the female trend towards cone-shaped skirts and male high cravats and dandyism. is a French fashion caricature by George Cruikshank.

is a French fashion caricature by George Cruikshank.

Russian Fashion

Spanish Fashion

Men's Fashion

Overview of Men's Styles

This period saw the complete disappearance of lace, embroidery, and other fancy decorations from serious men's clothing, except for formal court dress. These decorations wouldn't return until the 1880s. Instead, the way a garment was cut and tailored became much more important for showing its quality. This change happened partly because of a new interest in ancient times, sparked by discoveries like the Elgin Marbles. Figures in classical art were seen as perfect examples of the natural human form. The style for men in London became more refined, influenced by two things: the dandy and the romantic movement. The dandy (a man who cared a lot about his appearance but wanted to seem casual about it) appeared as early as the 1790s. Dark colors were almost always worn. However, "dark" didn't mean boring; many items, especially vests and coats, were made from rich, bright fabrics. Blue tailcoats with gold buttons were everywhere. White muslin shirts, sometimes with ruffles at the neck or sleeves, were very popular. Breeches were going out of style, replaced by pantaloons or trousers for everyday wear. Fabrics in general became more practical, with more wool, cotton, and buckskin instead of silk. So, in the 18th century, clothes became simpler, and tailoring became more important to show off the body's natural shape.

This was also when hair wax became popular for styling men's hair. Mutton chops became a fashionable style of facial hair.

Breeches became longer, with tight leather riding breeches reaching almost to the top of boots. They were replaced by pantaloons or trousers for fashionable street wear. The French Revolution played a big part in changing standard male dress. During the revolution, clothing showed the difference between the upper classes and the working-class revolutionaries. French rebels were called sans-culottes, meaning "people without breeches," because they made loose, floppy trousers popular.

Coats were cut away in the front with long skirts or tails behind. They had tall, standing collars. Lapels were not as large as in previous years and often had an M-shaped notch unique to this period.

Shirts were made of linen, had attached collars, and were worn with stocks or a cravat tied in various ways. Pleated ruffles at the cuffs and front opening went out of fashion by the end of this period.

Waistcoats were high-waisted and squared off at the bottom, but came in many styles. They were often double-breasted, with wide lapels and stand collars. Around 1805, large lapels that overlapped the jacket's lapels started to go out of fashion. The 1700s tradition of wearing the coat unbuttoned also faded, and waistcoats gradually became less visible. Before this, waistcoats often had vertical stripes, but by 1810, plain white waistcoats became more fashionable, as did horizontally striped ones. High-collared waistcoats were popular until 1815, then collars gradually lowered as the shawl collar became common towards the end of this period.

Overcoats or greatcoats were fashionable, often with collars made of contrasting fur or velvet. The garrick, sometimes called a coachman's coat, was a very popular style. It had three to five short capes attached to the collar.

Boots, usually Hessian boots with heart-shaped tops and tassels, were a main type of men's footwear. After the Duke of Wellington defeated Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815, Wellington boots became very popular. Their tops were knee-high in front and cut lower in the back. The jockey boot, with a folded-down cuff of lighter leather, had been popular before but continued to be worn for riding. Court shoes with raised heels became popular when trousers were introduced.

The Rise of the Dandy

The dandy, a man obsessed with clothes, first appeared in the 1790s in both London and Paris. In the slang of the time, a dandy was different from a "fop." A dandy's clothes were more refined and simple. The dandy prided himself on "natural excellence," and tailoring helped to exaggerate the natural body shape under fashionable outerwear.

In High Society: A Social History of the Regency Period, 1788–1830, Venetia Murray writes:

Other admirers of dandyism have taken the view that it is a sociological phenomenon, the result of a society in a state of transition or revolt. Barbey d'Aurevilly, one of the leading French dandies at the end of the nineteenth century, explained:

"Some have imagined that dandyism is primarily a specialisation in the art of dressing oneself with daring and elegance. It is that, but much else as well. It is a state of mind made up of many shades, a state of mind produced in old and civilised societies where gaiety has become infrequent or where conventions rule at the price of their subject's boredom...it is the direct result of the endless warfare between respectability and boredom."

In Regency London dandyism was a revolt against a different kind of tradition, an expression of distaste for the extravagance and ostentation of the previous generation, and of sympathy with the new mood of democracy.

Beau Brummell set the fashion for dandyism in British society from the mid-1790s. His style was known for perfect personal cleanliness, spotless linen shirts with high collars, perfectly tied cravats, and beautifully tailored plain dark coats. This was very different from the fancy "maccaroni" style of the earlier 1700s.

Brummell stopped wearing his wig and cut his hair short in a Roman style called à la Brutus. This matched the popularity of classical styles in women's fashion. He also led the change from breeches to tight-fitting pantaloons or trousers. These were often light-colored for day and dark for evening, based on working-class clothing adopted by all classes in France after the Revolution. Brummell's reputation for good taste was so strong that, 50 years after he died, Max Beerbohm wrote:

In certain congruities of dark cloth, in the rigid perfection of his linen, in the symmetry of his glove with his hand, lay the secret of Mr Brummell's miracles.

Not every man who wanted to be as elegant as Brummell succeeded. These dandies were often made fun of in drawings and writings. Venetia Murray quotes from Diary of an Exquisite in The Hermit in London, 1819:

Took four hours to dress; and then it rained; ordered the tilbury and my umbrella, and drove to the fives' court; next to my tailors; put him off after two years tick; no bad fellow that Weston...broke three stay-laces and a buckle, tore the quarter of a pair of shoes, made so thin by O'Shaughnessy, in St. James's Street, that they were light as brown paper; what a pity they were lined with pink satin, and were quite the go; put on a pair of Hoby's; over-did it in perfuming my handkerchief, and had to recommence de novo; could not please myself in tying my cravat; lost three quarters of an hour by that, tore two pairs of kid gloves in putting them hastily on; was obliged to go gently to work with the third; lost another quarter of an hour by this; drove off furiously in my chariot but had to return for my splendid snuff-box, as I knew that I should eclipse the circle by it.

- Transformation of men's fashion during a lifetime

-

Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834) wearing a powdered wig tied in a queue, common around 1795.

-

Marquis de Lafayette later in his life, dressed in 1820s fashion.

Hairstyles and Hats

The French Revolution (1789-1799) in France and the Pitt's hair powder tax in 1795 in Britain effectively ended the fashion for wigs and powder in these countries. Younger fashionable men in both countries started wearing their own unpowdered hair in short curls, often with long sideburns, without a queue (a ponytail). New styles like the Brutus ("à la Titus") and the Bedford Crop became popular. These styles then spread to other European countries and places influenced by Europe, including the United States.

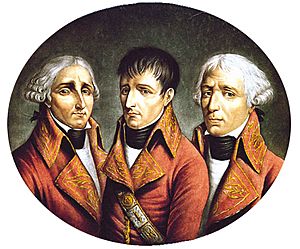

Many notable men during this period, especially younger ones, followed this new trend of short, unpowdered hairstyles. For example, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), who first wore long hair tied in a queue, changed his hairstyle and cut his hair short while in Egypt in 1798. Similarly, the future U.S. President John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), who had worn a powdered wig and long hair tied in a queue when he was young, stopped this fashion during this period while serving as the U.S. Minister to Russia (1809-1814). He later became the first president to have a short haircut instead of long hair tied in a queue. Older men, military officers, and those in traditional jobs like lawyers, judges, doctors, and servants kept their wigs and powder. Formal court dress in European monarchies also still required a powdered wig or long powdered hair tied in a queue until Napoleon became emperor (1804-1814).

Tricorne and bicorne hats were still worn. However, the most fashionable hat was tall and slightly cone-shaped. This hat would soon be replaced by the top hat, which would be the only hat for formal occasions for the next century.

Men's Style Gallery 1795–1809

of boxer "Jem" Belcher wearing a patterned cravat and a double-breasted brown coat with a dark collar, around 1800.

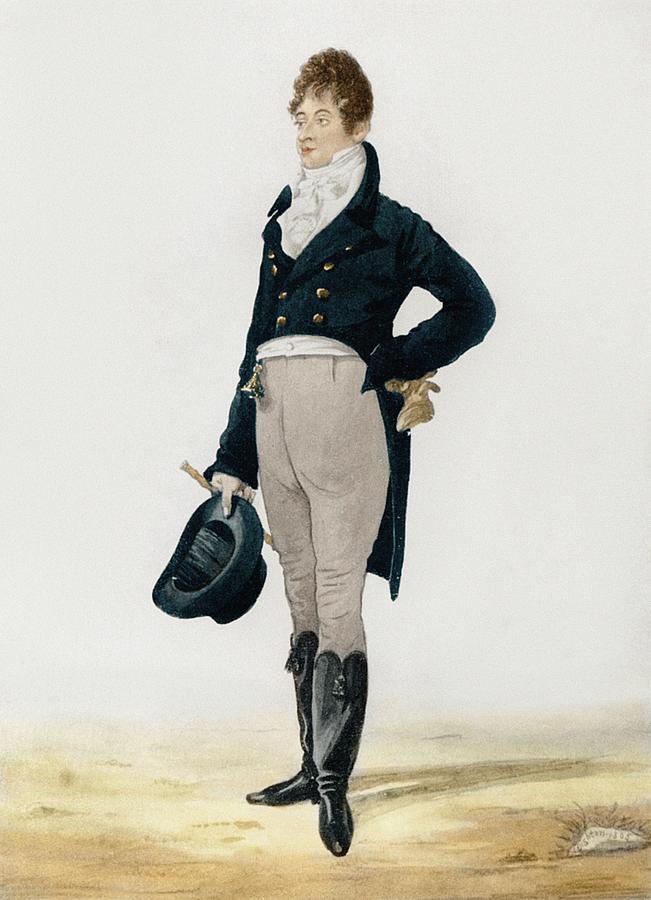

of boxer "Jem" Belcher wearing a patterned cravat and a double-breasted brown coat with a dark collar, around 1800. of Beau Brummell by Richard Dighton.

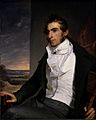

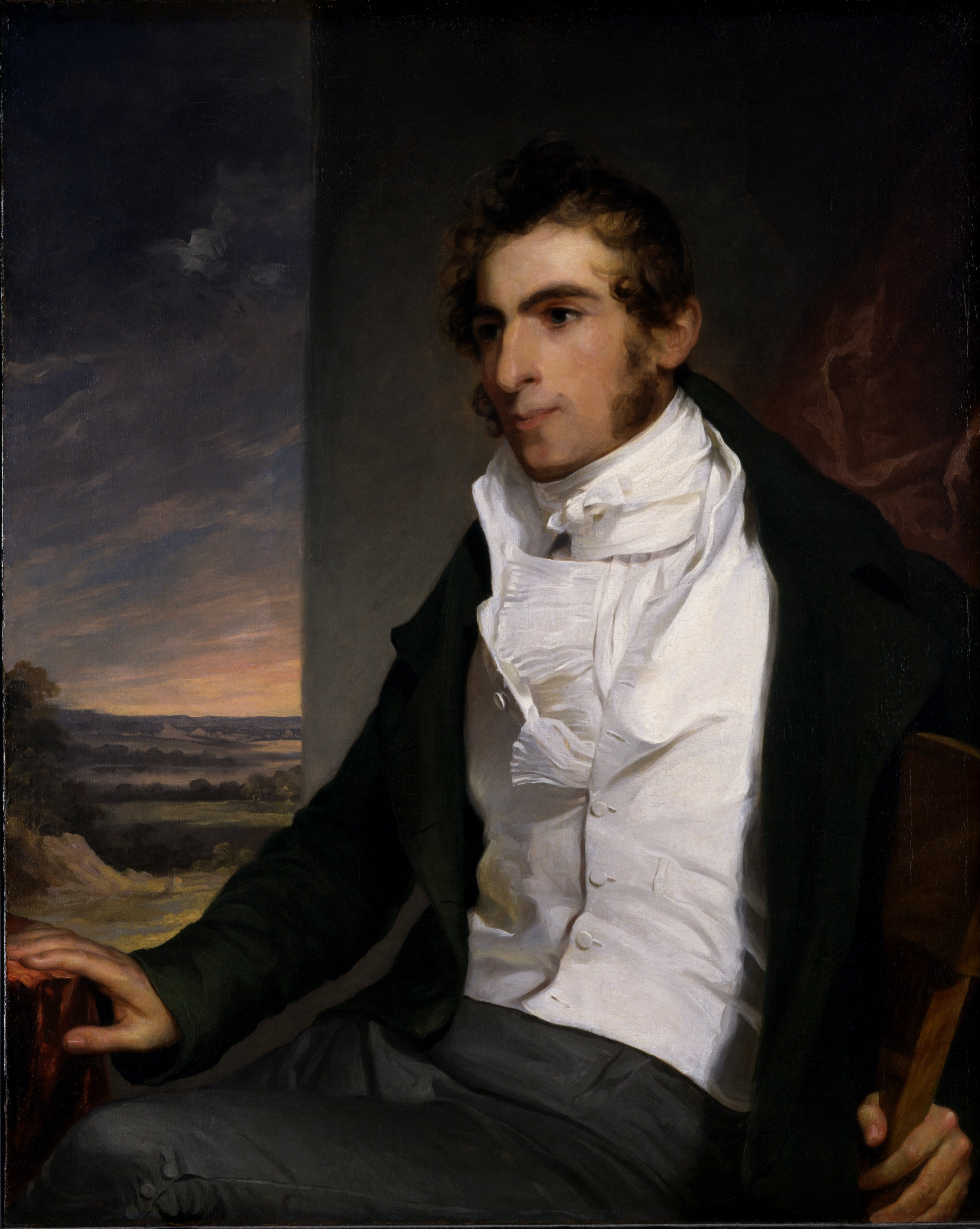

of Beau Brummell by Richard Dighton. from 1805, Washington Allston wears a tan cravat with his high white collar and dark coat. From Boston.

from 1805, Washington Allston wears a tan cravat with his high white collar and dark coat. From Boston. wears a white waistcoat with a tall, upright, notched collar over his high shirt collar and wide cravat. From America, 1807.

wears a white waistcoat with a tall, upright, notched collar over his high shirt collar and wide cravat. From America, 1807. wears a brown double-breasted coat with a contrasting collar and brass buttons. The ruffled front of his shirt can be seen next to the knot of his white cravat. From Germany, 1808–09.

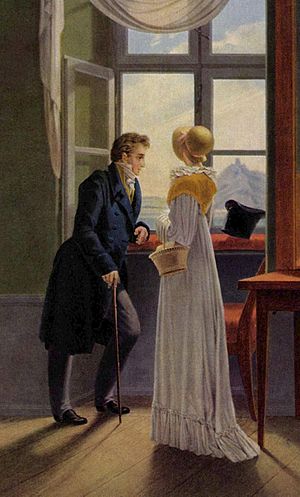

wears a brown double-breasted coat with a contrasting collar and brass buttons. The ruffled front of his shirt can be seen next to the knot of his white cravat. From Germany, 1808–09. has fashionable messy hair. He wears a long redingote over his coat, a tan waistcoat, a white shirt, and a dark cravat, 1808.

has fashionable messy hair. He wears a long redingote over his coat, a tan waistcoat, a white shirt, and a dark cravat, 1808. collar reaches his chin, and his cravat is wrapped around his neck and tied in a small bow. His short hair is styled casually and falls over his forehead, 1809.

collar reaches his chin, and his cravat is wrapped around his neck and tied in a small bow. His short hair is styled casually and falls over his forehead, 1809. of Gwyllym Lloyd Wardle shows him in a dark coat over a tan waistcoat and a high collar and cravat, 1809.

of Gwyllym Lloyd Wardle shows him in a dark coat over a tan waistcoat and a high collar and cravat, 1809. remained a feature of formal court suits, like this one. It has a red wool coat with a silver cloth waistcoat, both embroidered with silver thread. From Italy, around 1800–1810. At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

remained a feature of formal court suits, like this one. It has a red wool coat with a silver cloth waistcoat, both embroidered with silver thread. From Italy, around 1800–1810. At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. of Danish adventurer Jørgen Jørgensen shows how men's fashion was seen in Scandinavia during the Age of Revolution.

of Danish adventurer Jørgen Jørgensen shows how men's fashion was seen in Scandinavia during the Age of Revolution.

Men's Style Gallery 1810–1820

is a funny drawing about French fashions of 1810. It shows long, tight breeches or pantaloons, short coats with tails, and huge cravats.

is a funny drawing about French fashions of 1810. It shows long, tight breeches or pantaloons, short coats with tails, and huge cravats. wears a high-collared shirt with a dark cravat. He has a light-colored waistcoat, a double-breasted brown coat with covered buttons, and a dark gray overcoat with a contrasting collar (maybe sealskin). From 1810. His bicorne hat is on the table.

wears a high-collared shirt with a dark cravat. He has a light-colored waistcoat, a double-breasted brown coat with covered buttons, and a dark gray overcoat with a contrasting collar (maybe sealskin). From 1810. His bicorne hat is on the table. , a merchant and landowner from Baltimore, Maryland, poses in a romantic way. This shows details of his white waistcoat, ruffled shirt, and fall-front breeches with covered buttons at the knee, 1812–13.

, a merchant and landowner from Baltimore, Maryland, poses in a romantic way. This shows details of his white waistcoat, ruffled shirt, and fall-front breeches with covered buttons at the knee, 1812–13. wears a striped waistcoat under a black double-breasted coat, 1813.

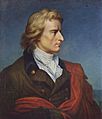

wears a striped waistcoat under a black double-breasted coat, 1813. wears a ruffled shirt with a knotted white cravat.

wears a ruffled shirt with a knotted white cravat. wears a double-breasted coat that shows a bit of the waistcoat underneath. He has tight pantaloons tucked into boots, and a high collar and cravat, 1816.

wears a double-breasted coat that shows a bit of the waistcoat underneath. He has tight pantaloons tucked into boots, and a high collar and cravat, 1816.- Nicolas-Pierre Tiolier wears a rich blue tailcoat and brown fall-front trousers over a white waistcoat, shirt, and cravat. His tall hat sits on an antique stand, 1817.

wears a double-breasted tailcoat with turned-back cuffs and a matching high velvet (or possibly fur) collar. Notice that while the man's slim waist isn't exaggerated like in some fashion drawings, it is clearly and intentionally narrowed. It's very likely the person in this portrait wore some kind of tight corset or similar undergarment. The coat sleeves are puffed at the shoulder. He wears a white waistcoat, shirt, and cravat, and light-colored pantaloons, 1819.

wears a double-breasted tailcoat with turned-back cuffs and a matching high velvet (or possibly fur) collar. Notice that while the man's slim waist isn't exaggerated like in some fashion drawings, it is clearly and intentionally narrowed. It's very likely the person in this portrait wore some kind of tight corset or similar undergarment. The coat sleeves are puffed at the shoulder. He wears a white waistcoat, shirt, and cravat, and light-colored pantaloons, 1819.

Children's Fashion

Both boys and girls wore dresses until they were about four or five years old. At that age, boys were "breeched", meaning they started wearing trousers.

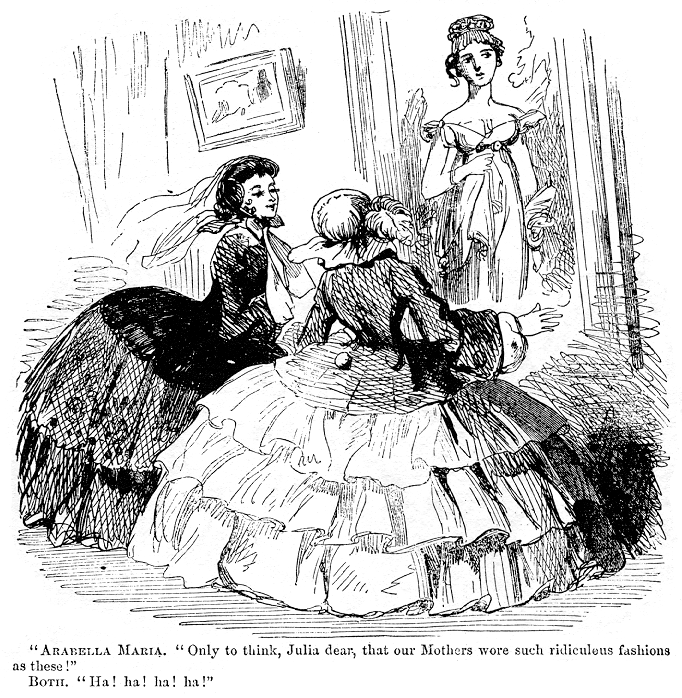

How Directoire, Empire, and Regency Fashions Were Seen Later

During the first half of the Victorian era, people generally had a negative view of women's styles from 1795–1820. Some might have felt a bit uncomfortable being reminded that their mothers or grandmothers once wore such styles. Many found it hard to relate to or take seriously heroines in art or literature if they were constantly reminded of these clothes. Because of this, some Victorian history paintings of the Napoleonic wars purposely avoided showing accurate women's styles. For example, Thackeray's illustrations for his book Vanity Fair showed women from the 1810s wearing 1840s fashions. In Charlotte Brontë's 1849 novel Shirley (set in 1811–1812), neo-Grecian fashions are wrongly placed in an earlier generation.

Later in the Victorian period, the Regency era seemed far away and less threatening. Kate Greenaway and the Artistic Dress movement brought back some elements of early 1800s fashions. In the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, many paintings and sentimental cards showed loose depictions of 1795–1820 styles. These were then seen as charming relics of a past era. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a small fashion revival of the Empire silhouette.

In recent years, 1795–1820 fashions are most strongly linked to Jane Austen's books, thanks to the many movie adaptations of her novels. There are also some common myths about Regency fashion. For example, the idea that women dampened their gowns to make them even more sheer. This was certainly not practiced by most women of the period.

making fun of how people disliked early 1800s clothes at the time.

making fun of how people disliked early 1800s clothes at the time. (1868) is a painting from the mid-Victorian era. It purposely does not show accurate women's styles from 1815.

(1868) is a painting from the mid-Victorian era. It purposely does not show accurate women's styles from 1815. (1882) is a later Victorian painting. It uses the Regency period to create a feeling of nostalgia.

(1882) is a later Victorian painting. It uses the Regency period to create a feeling of nostalgia. by Kate Greenaway.

by Kate Greenaway.

See Also

- Almack's

- Beau Brummel

- Corset controversy

- Dandy

- History of fashion

- Lady Caroline Lamb

- Regency dance

- Season (society)

- White's

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |