Architecture of Scotland in the Industrial Revolution facts for kids

The Architecture of Scotland in the Industrial Revolution covers all the buildings made in Scotland from the mid-1700s to the end of the 1800s. During this time, Scotland changed a lot because of the Industrial Revolution. This big change led to new ways of building, new styles, and much larger buildings.

In the late 1700s, Edinburgh became a hub for building in a classical style. This showed how rich and confident the city was becoming. Many homes were built as tenement flats, which are apartments divided horizontally. Famous Scottish architects like Robert Adam and William Chambers were important in Europe during this time.

Cities like Aberdeen used local granite, and Glasgow used red sandstone for their buildings. However, homes for poor people in the countryside, especially in the Highlands, stayed very simple. In cities, many poor people lived in crowded tenements, like those in the Gorbals area of Glasgow. To deal with the growing population, people started building planned new towns, such as Inverary and New Lanark.

The 1800s also saw the return of the Scots Baronial style. This style became popular after Walter Scott rebuilt his home, Abbotsford House. Its popularity grew even more when Queen Victoria chose Balmoral Castle as her home. Gothic styles also came back, especially for churches. Neo-classicism remained important, with architects like William Henry Playfair and Alexander "Greek" Thomson. Later in the century, new engineering methods led to amazing structures like the famous Forth Bridge.

Contents

Building in the Late 1700s

The Neo-classical Style

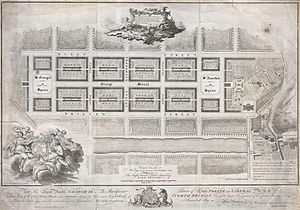

During the Industrial Revolution, Scotland became a major business and industrial centre for the British Empire. From the mid-1700s, this new wealth led to a building boom in Edinburgh's New Town. This area was designed with rectangular blocks and open squares. James Craig (1739–95) drew up the plan. Buildings were made from strong Craigleith sandstone, which masons could cut very precisely.

Most homes were tenement flats, divided horizontally. Different families shared a common staircase. This was different from England, where single houses were more common. The smallest flats might have one room, while larger ones had many bedrooms and living areas. Neo-classical buildings often featured columns, temple-like fronts, rounded arches, and domes. Because of this classical style and its role in the Enlightenment, Edinburgh was called "The Athens of the North." Many smaller towns copied this grid plan and building style, using local stone.

Even with this building boom, many Scottish architects worked in England. This was because much of the government's building work was based in London. Robert Adam (1728–92) became a leader in the neo-classical style in both England and Scotland from about 1760. He thought the older Palladian style was too heavy. Adam was inspired by ancient Greek and Roman buildings. He saw excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, which showed him classical buildings firsthand. Neo-classicism aimed for simpler designs, often inspired by Greek rather than Roman styles.

Adam's main works in Edinburgh included the General Register House (1774–92), the University Building (1789), and Charlotte Square (1791). He also designed 36 country houses in Scotland. Adam and his brothers, John (1721–92) and James (1732–94), created the Adam style. This style influenced architecture not just in Britain, but also in Europe, North America, and Russia.

Adam's main competitor was William Chambers (1723–96), who was Scottish but born in Sweden. He worked mostly in London, with only a few houses in Scotland. Chambers was a tutor to Prince of Wales (later George III). In 1766, he became Architect to the King, along with Robert Adam. Chambers had a more international view, mixing Neo-classicism with Palladian ideas. Many of his students spread his influence.

The classical style also reached church architecture. Scottish architect James Gibbs (1682–1754) used an antique style for St Martin-in-the-Fields in London. It had a large, steepled portico and a rectangular plan. Similar churches in Scotland include St Andrew's in the Square, Glasgow (1737–59), designed by Allan Dreghorn (1706–64). Gibbs' own design for St. Nicholas West, Aberdeen (1752–55), had a similar rectangular layout.

Building in the Early 1800s

Local Building Styles

Local building styles, called vernacular architecture, continued to use materials found nearby. Poor people's homes in the countryside were usually very simple. Friends and family often built them together. People at the time noted that cottages in the Highlands and Islands were often rougher. They had one room, narrow windows, and dirt floors. Often, a large family shared the space. In contrast, many Lowland cottages had separate rooms, plastered or painted walls, and even glass windows. In the early 1800s, towns still had traditional thatched houses next to larger stone and slate-roofed homes of merchants.

The Industrial Revolution greatly changed Scottish towns. Glasgow became the "second city of the Empire." Its population grew from 77,385 in 1801 to 274,324 by 1841. Between 1780 and 1830, three middle-class "new towns" were built south and west of Glasgow's old town. They had grid-iron plans, similar to Edinburgh's New Town.

However, with increasing wealth and planned architecture for the rich, there was also a lot of unplanned growth. In Glasgow, many new suburban tenements were quickly built for the growing number of workers. Areas like the Gorbals in the south became very crowded. Poor sanitation and poverty led to disease, crime, and very short lifespans.

Cities increasingly used local stone. Edinburgh used a lot of yellow sandstone. Glasgow's business centre and tenements were built with distinct red sandstone. After a big fire in the mostly wooden city of Aberdeen in the 1740s, city leaders decided that major buildings should be made of the locally available granite. This started a new period of large-scale quarrying. Aberdeen became a major centre for the granite industry, supplying stone to Scotland and England.

New Towns

The idea of a new town was important in Scotland from the mid-1700s to the 1900s. These towns aimed to improve society by creating well-designed communities. Besides Edinburgh's New Town, other examples include the rebuilding of Inverary for John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll. This was done by John Adam (1721–92) and Robert Mylne (1733–1811) between 1772 and 1800. Helensburgh, near Glasgow, was laid out in 1776 with a grid-iron plan.

Smaller new towns with grid plans built between 1770 and 1830 included Cuminestown, New Pitsligo, Tomintoul, and Aberchirder. At Fochabers, from 1776, John Baxter redesigned the village with a grid plan. It had a central square focused on Bellie Church (1795–97), which still followed Gibbs' style with a tetrastyle portico and steeple.

From 1800, Robert Owen's New Lanark was a key step in urban planning. It was designed as a complete community, mixing industry with organized and better living conditions. Homes were combined with large shared spaces, a children's school, and a community education centre. It also had a village store that sold goods at lower prices, becoming a model for the co-operative movement. Scotland also produced a major figure in urban planning, Patrick Geddes (1854–1932). He developed the idea of conurbation (when cities grow together). He preferred "conservative surgery" over "sweeping clearances" of old housing. This meant keeping the best buildings and removing the worst. He put this into practice in Edinburgh, buying and improving old tenements.

Decline of Neo-classical Style

In the early 1800s, the Gibbs-influenced steeple style continued in church architecture. Examples include Robert Nisbet's Inveresk Church (1803–10). A Greek style appeared at William Burn's North Leith Church (1813) and St John's Episcopal Church, Edinburgh (1816). A disagreement over the style of the Scottish National Monument in 1816 led to Greek temple designs being called "pagan." After that, fewer Greek-style churches with columns were built in Edinburgh.

An exception was Archibald Elliot's Broughton Church (1820–21), which had a Doric temple front. More common in Edinburgh were churches that mixed classical elements with other features. Examples include the domed St George's, Charlotte Square (1811–14), by Robert Reid. Another is the Gracco-Baroque William Playfair's St Stephen's (1827–28).

In Glasgow, it was common to add porticoes to existing meeting-houses. This continued with Gillespie Graham's West George Street Independent Church (1818). John Baird I's Greyfriars United Secession Church (1821) had a Roman Doric portico. Classical designs for the official Church included the redevelopment of St George's-Tron Church (1807–08) by William Stark. Also, David Hamilton's (1768–1843) St Enoch's Parish Church (1827) and St Paul's Parish Church (1835) were built.

Building in the Late 1800s

Gothic Revival

Some of the earliest signs of a return to Gothic architecture appeared in Scotland. Inveraray Castle, built from 1746 with help from William Adam, included turrets. These were mostly traditional Palladian houses that added some outside features of the Scots Baronial style.

Robert Adam's houses in this style include Mellerstain and Wedderburn in Berwickshire. But it is most clearly seen at Culzean Castle, Ayrshire, which Adam redesigned from 1777. Features borrowed from 1500s and 1600s houses included battlemented gateways, crow-stepped gables, pointed turrets, and machicolations.

Abbotsford House, the home of writer Sir Walter Scott, was very important for making the style popular in the early 1800s. Rebuilt for him from 1816, it became a model for the modern Baronial style. This style was used by architects like Edward Blore (1787–1879) and Robert Stodart Lorimer (1864–1929). It appeared in city areas, like Cockburn Street in Edinburgh (from the 1850s), and for monuments like the National Wallace Monument at Stirling (1859–69).

Robert Billings' (1813–74) multi-volume book Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1848–52) helped spread the style. The rebuilding of Balmoral Castle as a baronial palace and its use as a royal retreat from 1855 to 1858 made the style even more popular.

In church architecture, a style similar to England's was adopted. It was based on late Medieval designs, often using arched windows, stained glass, and carvings. Important architects included Frederick Thomas Pilkington (1832–98). He created a new church building style that matched the popular High Gothic. He adapted it for the needs of the Free Church of Scotland, as seen at Barclay Viewforth Church, Edinburgh (1862–64).

Robert Rowand Anderson (1834–1921) trained in London before returning to Edinburgh. He mostly worked on small churches in the 'Early English' style. By 1880, his firm was designing some of Scotland's most important public and private buildings. These included the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, parts of the University of Edinburgh, the Central Hotel at Glasgow Central station, and Mount Stuart House on the Isle of Bute.

Classical Revival

Even though Scots Baronial and Gothic styles became popular, Neo-classicism remained a major style into the 1800s. William Henry Playfair (1790–1857) designed many of Edinburgh's neoclassical landmarks in the New Town. Two of his best works are the National Gallery of Scotland and the Royal Scottish Academy, both in central Edinburgh.

However, the architect most linked with the classical style was Alexander "Greek" Thomson (1817–75). Working mainly in Glasgow, he moved away from the Gothic style. He preferred the styles of ancient Greeks and Egyptians. This can be seen in the temple and columns of the Caledonia Road Church (1856).

David Rhind (1808–83) used both neoclassical and Baronial styles. His work included many branches of the Commercial Bank of Scotland, including their headquarters in Edinburgh. He also designed churches, local government buildings, and houses. One of his biggest projects was Daniel Stewart's Hospital, now Stewart's Melville College, Edinburgh. In 1849, he was asked to design the Pollokshields area of Glasgow. This area, 2 miles (3.2 km) south of the city centre, had been farmland.

Rhind partnered with Robert Hamilton Paterson (1843–1911). They completed major works for brewers and warehouse owners. Edinburgh was a centre for these industries. Their projects included designs for Abbey, James Calder & Co., Castle, Holyrood, Drybrough's, Caledonian, and Clydesdale Breweries. They also worked for McVitie and Price. The partnership also completed important projects like the Queen Victoria Memorial at Liverpool and the Royal Scots War Memorial in St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh.

New Engineering

The 1800s saw some huge engineering projects. These included Thomas Telford's (1757–1834) stone Dean Bridge (1829–31) and iron Craigellachie Bridge (1812–14). In the 1850s, new ways of building with wrought- and cast-iron were explored for commercial warehouses in Glasgow. This style used round arches, similar to Venetian designs. Alexander Kirkland (1824–92) first used it at 37–51 Miller Street (1854). John Baird I's Gardner's Warehouse (1855–6) used iron, with an exposed iron frame and almost all glass windows. Most industrial buildings did not use this cast-iron look. For example, William Spence's (1806?–83) Elgin Engine Works (1856-8) used massive rough stone blocks.

The most important engineering project was the Forth Bridge. This cantilever railway bridge crosses the Firth of Forth in eastern Scotland. It is about 9 miles (14 km) west of central Edinburgh. Construction of a suspension bridge designed by Thomas Bouch (1822–80) was stopped. This happened after another of his bridges, the Tay Bridge, collapsed.

The project was taken over by John Fowler (1817–98) and Benjamin Baker (1840–1907). They designed a new structure. The Glasgow-based company Sir William Arrol & Co. built it from 1883. It opened on March 4, 1890, and spans a total length of 8296 feet (2529 m). It was the first major structure in Britain to be built of steel. The Eiffel Tower, built around the same time, was made of wrought iron.

See Also

- Architecture in early modern Scotland

- Architecture in modern Scotland

- Architecture of Scotland