British industrial architecture facts for kids

British industrial architecture is all about the amazing buildings made in Britain, mostly since the 1700s. These buildings were made to house all sorts of industries. Britain was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution during this time.

The new ways of making things and the special buildings for them quickly spread worldwide. So, the old industrial buildings we still see today tell us a lot about modern history.

Some factories were easy to spot because of their unique shapes. Think of tall glass cones for glass factories or bottle kilns for pottery. Transport also changed a lot. First, a huge network of canals was built. Then, railways came along. These brought us famous structures like the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and the Ribblehead Viaduct.

New materials like reinforced concrete and steel became available. This allowed builders to create totally new kinds of structures. Industrial architects loved to try different styles for their buildings. Some looked like ancient Egyptian temples, while others looked like medieval castles or grand country houses. Some even looked like Venetian Gothic palaces!

Other buildings were designed to be super impressive because of their size. For example, the India Mill in Darwen had a really tall chimney. Some buildings proudly showed off how modern they were. The "heroic" Power House, Chiswick even had statues of "Electricity" and "Locomotion." In the 1900s, many company headquarters, like the Art Deco Hoover Building, were built in a "By-pass modern" style. These long, white buildings were placed right next to major roads outside London.

Contents

The Industrial Revolution Begins

Early Factories and Iron

Around 1700, a man named Abraham Darby I made Coalbrookdale a very important place. He started making things from cast iron, like cooking pots. This was a big part of the Industrial Revolution. Later, his grandson, Abraham Darby III, built the famous The Iron Bridge across the Coalbrookdale Gorge. This bridge was made from cast iron sections.

The company's Bedlam Furnaces were even painted in a famous picture called Coalbrookdale by Night in 1801. The Iron Bridge inspired engineers and architects all over the world. It was one of the first large structures made of cast iron. Today, the gorge is a World Heritage site.

How Industries Grew

From 1700 onwards, Britain's economy changed a lot. Industries grew, trade increased, and many new things were invented. This made Britain the first country to become industrial. More and more people started working in factories, especially in northern England.

The Industrial Revolution brought new ways to make iron using coke. It also brought iron puddling, steam engines, and machines for making textiles. Work was organized in factories where many steps of making a product happened in one place.

Some industries, like steelmaking in Sheffield and textile making in Lancashire, left behind many large buildings. Other industries, like mining, left fewer traces. Farmers also had buildings like corn mills, malt houses, breweries, and tanneries. These became more advanced over time. Around 1800, multi-story corn mills appeared because war made grain prices go up.

Murrays' Mills in Manchester started in 1798. It became the longest mill building in the world. These cotton mills were built right next to the Rochdale Canal. This gave them easy access to the transport network of the 1700s.

-

The multi-story corn mill at Stamford Bridge, around 1800.

-

Murrays' Mills (for cotton) on the Rochdale Canal, Manchester. It started in 1798.

Building Transport Networks

As industries grew, a huge network of canals was quickly built. These canals could carry heavy goods across the country. Canals were dug to connect factories to their customers. For example, the 1794 Glamorganshire Canal linked ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil to the harbor in Cardiff. This helped industries grow very fast in the South Wales Valleys.

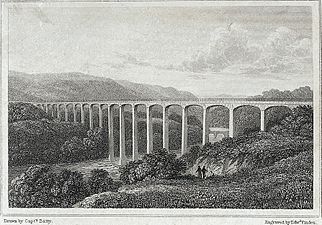

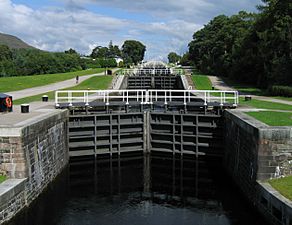

The engineer Thomas Telford built some amazing canals. Between 1795 and 1805, he built the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct. This aqueduct is 126 feet (38 meters) high and carries the Llangollen Canal over the River Dee, Wales. From 1803 to 1822, he built the Caledonian Canal in Scotland. This canal links a chain of lakes and includes the huge Neptune's Staircase. This is a series of eight large locks, each 180 feet (55 meters) long and 40 feet (12 meters) wide. Together, they lift barges 64 feet (20 meters) up!

Shipbuilding Wonders

Chatham Dockyard on the River Medway in Kent was a very important place. It built and equipped ships for the Royal Navy for over 400 years, starting with Henry VIII. It always used the newest technology for its ships and buildings.

No. 3 covered slip at Chatham Dockyard had a roof over a ship-building area. This kept the wood of the ship dry and strong. Its wooden roof trusses were built in 1838. No. 7 covered slip, built in 1852, was one of the first to use metal trusses for its roof.

Buildings Shaped by Their Purpose

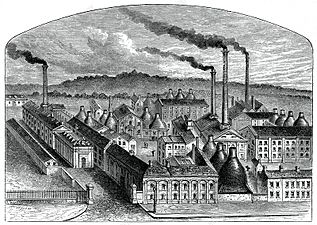

Some industrial buildings had very clear designs based on what they did. For example, glass cones were used in glassworks. Bottle ovens were used in places like the Staffordshire Potteries or the Royal Worcester porcelain works.

The tapering roofs of oast houses were used to dry hops for beer in Kent. And Scotch whisky distilleries often had pagoda-like vents on their roofs.

-

The unique glass cones of Lemington Glass Works, Newcastle upon Tyne, around 1900.

-

A bottle kiln for firing ceramics at Gladstone Pottery Museum, early 1800s.

-

An engraving of The Royal Worcester porcelain works, around 1880.

Britain: The World's Workshop

Designed to Impress

By the mid-1800s, Britain was called the "workshop of the world." Industries grew very fast, helped by the new railway network. Railways made it easy to move goods. This meant factories could be built far from where raw materials like coal were found. Steam engines powered all kinds of mills. Cotton mills, for example, no longer needed to be next to a fast-flowing river. Iron foundries and blast furnaces also became much bigger.

The money made from these new industries allowed factory owners to build impressive buildings. A cotton boss named Eccles Shorrock hired Ernest Bates to design his India Mill in Darwen, Lancashire. It had a showy, 300-foot (91-meter) tall chimney in the style of an Italian campanile. This chimney was made of red, white, and black bricks. It had stone decorations and a fancy top with over 300 cast iron pieces.

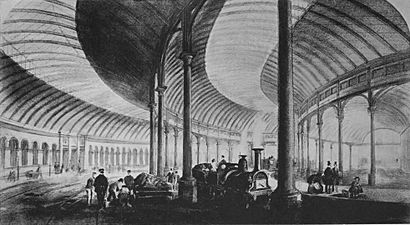

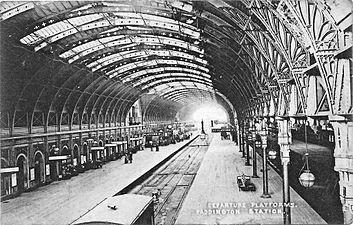

Railway Cathedrals

Britain's railways, the first in the world, changed everyday life and industry. They made transport incredibly fast. Railways showed off their importance with grand architecture. These buildings looked back to the past but also celebrated the future. The French poet Théophile Gautier called the new railway stations "cathedrals of the new humanity."

Newcastle Central station got a fully covered roof in 1850. It's the oldest surviving one in the country. Bristol Temple Meads railway station looks like a cathedral from the outside. It has Gothic arches and a tall, pointed tower. The old station there, built in 1841, had a hammerbeam roof. People said it was like the roof of Westminster Hall. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the engineer for the Great Western Railway, even called the station "a cathedral to the iron horse." London Paddington station was also designed by Brunel. He was inspired by Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace and the München Hauptbahnhof in Germany.

Trying Out Different Styles

Industrial architects loved to experiment with non-industrial styles. One early example was Egyptian Revival. This style became popular after Napoleon's journey to Egypt. Joseph Bonomi designed the Temple Works flax mill offices in Leeds. They looked like the Mammisi (a special building) at the Dendera Temple complex in Egypt. This was built from 1836 to 1840.

At Stoke Newington, the Metropolitan Water Board's engine house was built to look like a medieval castle. It even had towers and battlements! The pumping station at Ryhope, Sunderland, was built in 1869. It looks a bit like Jacobean style with curved Dutch gables. It also has an octagonal brick chimney. One historian called it a "cathedral of pistons and brass."

The Bliss Tweed Mill in Chipping Norton was designed in 1872 by George Woodhouse. It was built from local limestone. Even though it has 5 stories, it looks like a grand Charles Barry-style English country house. It also has a big chimney. The chimney and curved stairwell tower are off-center. The corners have railings and urns on top.

The Templeton Carpet Factory in Glasgow is famous for its colorful brickwork. It was built in 1892 by William Leiper for making Axminster carpets. It was designed in Venetian Gothic style, just like the Doge's Palace in Venice.

Famous Landmarks

Some industrial structures became famous landmarks. The Ribblehead Viaduct carries the Settle–Carlisle railway across the Ribble Valley in North Yorkshire. It was built by the Midland Railway and opened in 1876. It's 440 yards (400 meters) long and 104 feet (32 meters) high. It's now a much-loved, Grade II*-listed building.

Gas for heating homes, made from coal, was stored in huge round gasholders. Their iron frames still stand in some places today. They are like memorials to industries that are no longer around. Examples include the Bromley-by-Bow or Oval gasholders.

Moving Towards Modern Design

The Power House, Chiswick is an electricity generating station. It was designed in 1901 for the London United Electrical Tramway Company. One historian called it a "monumental" building from the "early, heroic era of generating stations." It has huge stone arches. Above the entrance are two large stone figures. One is "Electricity," with her foot on a globe and lightning coming from her hand. The other is "Locomotion," with her foot on an electric tram and her hand on a winged wheel.

Arthur Sanderson & Sons' wallpaper printing works in Chiswick was designed by the modernist architect Charles Voysey in 1902. This was his only industrial building. It has white glazed bricks with horizontal bands of Staffordshire blue bricks. The base, doors, and windows are made of Portland stone. It's seen as an important Arts and Crafts factory building.

Charles Holden's modern station buildings for the London Underground mixed round shapes with flat surfaces. A good example is his "futuristic" 1933 Arnos Grove tube station. It has a bright, circular ticket hall made of brick with a flat concrete roof.

-

Modernist wallpaper printing works for Sandersons by Charles Voysey, Chiswick, 1902.

-

Charles Holden's "futuristic" Arnos Grove tube station, built in 1933.

New Ways to Build

Along with new styles, new ways of building also appeared. William T. Walker's 1903–1904 Clément-Talbot car factory in Ladbroke Grove had a traditional-looking office entrance. It was made of red brick with stone pillars and a fancy entrance for carriages. This impressive front led to a marble-floored showroom. But the main factory behind it was one of the first buildings to use reinforced concrete.

New materials like steel and concrete allowed for completely new designs. The Tees Transporter Bridge is a great example. Its foundations are concrete, poured deep into the ground. The bridge itself is made of steel with granite supports.

Between the World Wars (1914-1945)

"By-pass Modern" Style

The idea of a "daylight factory" came from America. These factories had long, sleek buildings and nice grassy areas around them. They often had huge windows and were built along major roads, like the Great West Road in Brentford. This is why they were called "by-pass modern" factories.

A famous example is the Hoover Building in the Art Deco style, built by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners from 1932 to 1935. At the time, some people didn't like it because it looked too commercial. But now, it's a protected building. One historian called it "the cathedral of modernism" and "an icon of 1930s design."

Art Deco Meets Ancient Egypt

A very different building from between the wars is the Carreras Cigarette Factory. It was built from 1926 to 1928 in Mornington Crescent, Camden. It was designed by M. E. Collins, O. H. Collins, and A. G. Porri. They mixed Art Deco and Egyptian Revival styles.

The factory is 550 feet (168 meters) long. It has a continuous top edge with red and blue lines. It was built with modern pre-stressed concrete. But it was decorated to look like ancient Egypt, after Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered in 1922. The company used a black cat, like the Egyptian cat god Bastet, as its symbol. They even put two large cat statues by the entrance and smaller cat designs on the building.

Modern Industrial Buildings

After World War II

Since the Second World War, architects have created amazing industrial buildings. They use modern or post-modern styles. One example is the British Gas Engineering Research Station at Killingworth. It was built in 1967 and designed by Ryder and Yates. It's considered a "masterpiece" of post-war architecture.

CZWG's Aztec West in Bristol uses horizontal stripes of brick. It has tall, narrow windows and white concrete edges that look like pillars. Its symmetrical, curved buildings also remind some people of the Art Deco style.

21st Century Designs

A great example of architecture and engineering working together is Heathrow Airport's Terminal 5 building. It opened in 2008. It's 1,299 feet (396 meters) long, 577 feet (176 meters) wide, and 130 feet (40 meters) tall. This makes it the largest free-standing building in Britain. Its roof is held up by exposed hinged trusses.

The architects were Richard Rogers Partnership and Pascall+Watson. The engineers were Arup for the parts above ground and Mott MacDonald for the underground structures.

|

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |