Robert Adam facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Adam

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait attributed to George Willison, c. 1770–1775

|

|||||||||||

| Born | 3 July 1728 |

||||||||||

| Died | 3 March 1792 (aged 63) |

||||||||||

| Burial place | Westminster Abbey | ||||||||||

| Nationality | British | ||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh | ||||||||||

| Style | Neoclassical | ||||||||||

| Parent(s) |

|

||||||||||

| Relatives |

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Robert Adam (1728–1792) was a famous British architect. He was also an interior and furniture designer. He is known for his unique "Adam Style." This style mixed old Roman and Greek designs with new ideas.

Robert learned from his father, William Adam. William was Scotland's top architect at the time. After his father died, Robert and his older brother John took over the family business. They worked on many projects, including for the government.

In 1754, Robert traveled to Rome. He spent almost five years studying architecture in Europe. He learned from famous artists and architects. When he came back to Britain, he started his own business in London. His younger brother James joined him.

Robert Adam became one of the most popular architects in the country. He designed beautiful homes and their interiors. He also helped shape the city of Edinburgh. From 1761 to 1769, he was the King's Architect. He also served in Parliament from 1768 to 1774.

Contents

About Robert Adam's Life

Growing Up in Scotland

Robert Adam was born on July 3, 1728. His family lived in Kirkcaldy, Scotland. His father, William Adam, was a well-known architect. Robert was the second of his parents' sons.

From age six, Robert went to the Royal High School, Edinburgh. He studied Latin there until he was 15. He read works by famous ancient writers like Virgil and Cicero.

In 1743, he started at the University of Edinburgh. He took classes in Greek, logic, and philosophy. He also studied math and anatomy. His studies were stopped when Bonnie Prince Charlie and his Highlanders took over Edinburgh in 1745. Robert then became very sick for several months. He likely did not return to university after that.

After getting better in 1746, Robert became an apprentice to his father. He helped with big projects like Inveraray Castle. He also worked on Hopetoun House. His father's work for the government also gave them many jobs. They helped build forts in Scotland. Robert's first dream was to be an artist. His early drawings show a love for old-style buildings.

Starting His Architecture Career

When William Adam died in 1748, his oldest son John took over the family business. John quickly made Robert his partner. Later, their younger brother James also joined them.

The Adam brothers' first big job was decorating Hopetoun House. Then they built their first new house, Dumfries House. They also worked on Fort George, Highland, a large modern fort. This project kept them busy every summer for ten years. These jobs gave Robert a lot of hands-on building experience.

In 1749, Robert traveled to London. He visited famous buildings like Wilton House. He also saw Roger Morris's Queens Hermitage. His drawings from this trip show he was still interested in older building styles.

Robert had many friends in Edinburgh. These included thinkers like David Hume and artists like Paul Sandby.

The Grand Tour Adventure

On October 3, 1754, Robert Adam began his "Grand Tour." This was a long trip through Europe. He stopped in London for a few days. He visited famous places like St Paul's Cathedral. Then he sailed to Calais, France.

He traveled with Charles Hope-Weir to Rome. Robert stayed in Rome until 1757. He studied ancient Roman buildings. He improved his drawing skills with teachers like Charles-Louis Clérisseau. He also learned from the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

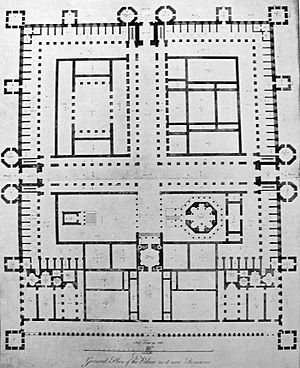

On his way back, Robert and Clérisseau studied the ruins of Diocletian's Palace. This palace was in a place called Spalatro (now Split, Croatia). Robert later published a book about these studies in 1764. It was called Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia.

Building a London Practice

Robert came back to Britain in 1758. He started a business in London with his brother James. They focused on designing entire homes. This included the decorations and furniture.

At the time, the Palladian style was popular. Robert designed many country houses in this way. But he also created his own new style. It used parts of old Roman, Greek, and other styles.

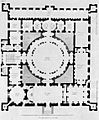

The Adam brothers were successful because they designed everything. From the biggest walls to the smallest doorknobs, everything matched. Carpets often had patterns that matched the ceilings. This made their designs feel complete and unified.

One of their biggest projects was the Adelphi in London. They bought land by the Thames River. They planned to build 24 houses there. This was a very ambitious project. It was the first time terraced houses were designed to look like one big, unified building.

However, the project ran into money problems. The brothers ended up with huge debts. In 1772, they had to let go of 3,000 workers. Robert himself moved into one of the Adelphi houses. In 1774, a public lottery helped them raise money. This saved them from going bankrupt.

Public Service and Recognition

In 1758, Robert became a member of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts. In 1761, he joined the Society of Antiquaries. That same year, he was named Architect of the King's Works. He shared this job with Sir William Chambers.

Robert left this royal job in 1768. He wanted to spend more time as a Member of Parliament. He represented Kinross-shire until 1774.

Robert Adam's Architectural Style

Adam did not like the Palladian style. He called it "heavy" and "unpleasant." But he still got ideas from ancient buildings. He had studied them for four years in Europe.

Adam created a new way to decorate buildings. It was more accurate to ancient designs. But it was also new and creative. He and his brother James wrote a book called Works in Architecture. They said that old Greek and Roman examples should be "models which we should imitate."

The Adam brothers' idea of "movement" was mostly Robert's. This idea used big contrasts and different shapes. It made buildings feel more exciting. Kedleston Hall, designed by Robert in 1761, is a great example of this "movement."

Robert also used "movement" in his interiors. He changed room sizes and decorations. His decorating style was called "Classical Rococo." It used Roman "grotesque" stucco designs.

Robert Adam's Impact

Robert Adam's work changed architecture and design around the world. In England, he worked with Thomas Chippendale. Together, they made some of the best neoclassical designs.

In North America, the Federal style was much like Adam's neoclassical work. In Europe, Adam influenced Charles Cameron. Cameron was a Scotsman who designed palaces in Russia for Catherine the Great.

By the time Robert Adam died, a simpler, more Greek style was becoming popular in Britain. Many artists who worked for the Adam brothers later became famous architects themselves.

Books by Robert Adam

Robert and James Adam published two books of their designs. They were called Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam. The first came out in 1773–1778. The second was published in 1779. A third book was published after Robert died in 1822.

Death and Burial

Robert Adam had stomach and bowel problems for a long time. On March 1, 1792, he became very ill. He died on March 3, 1792, at his home in London.

His funeral was held on March 10. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. Many important clients carried his coffin.

Robert never married. He left his property to his sisters.

His obituary (a notice of his death) was in The Gentleman's Magazine. It said that Robert Adam "produced a total change in the architecture of this country." It also said his "fertile genius in elegant ornament was not confined to the decoration of buildings." It noted that he designed many great works even in his last year.

Robert left almost 9,000 drawings. Most of these were bought by architect John Soane in 1833. They are now kept at the Soane Museum in London.

Buildings Designed by Robert Adam

Public Buildings

- Fort George, Scotland (1748–69) – completed by his sons after William Adam's death.

- The Argyll Arms, Inveraray (1750–56)

- The Town House, Inveraray (1750–57)

- Royal Exchange, Edinburgh, with his brother John (1753–54)

- Screen in front of the Old Admiralty, Whitehall, London (1760)

- Kedleston Hotel, Quarndon (1760)

- Little Market Hall, High Wycombe (1761) – later changed.

- Riding School, Edinburgh (1763) – now gone.

- Courts of Justice and Corn Market, Hertford (1768) – now Shire Hall. A joint project with James Adam.

- Pulteney Bridge, Bath (1770)

- County House, Kinross (1771)

- Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (1772)

- Register House, Edinburgh (1774–1789)

- Market Cross, Bury St Edmunds, refaced and upper floor added (1776)

- Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, remodeled (1775) – now gone.

- Red Lion Inn, Pontefract (1776)

- Drummonds Bank, Charing Cross, London (1777–78) – now gone.

- Home House, London (1777)

- Old College, University of Edinburgh, (1788-onwards) – finished later by William Henry Playfair.

- The Bridewell, Edinburgh (1791) – now gone.

- The Assembly Rooms, Glasgow (1791–94) – now gone.

- Trades Hall, Glasgow, Scotland (1791–1792) – finished by his brothers.

- The Royal Infirmary, Glasgow (1791–94) – rebuilt in 1914.

- Coutts Bank enclosed bridge, John Adam Street (1799) – later gone.

Churches

- Yester Chapel, Lothian, new west front in Gothic style (1753)

- Cumnock church, Ayrshire (1753–54) – now gone.

- St. Mary Magdalene, Croome Park, interior (1761–63)

- St. Andrew's Church, Gunton Hall, Norfolk (1769)

- St Mary's, Mistley (1776) – only the towers remain.

- St. George's Chapel, Edinburgh (1792) – now gone.

Mausoleums (Tombs)

- William Adam Mausoleum, Greyfriars Kirkyard (1753–55)

- Bowood House Mausoleum (1761–64)

- David Hume Mausoleum, Old Calton Cemetery (1777–78)

- Templetown Mausoleum, Castle Upton, County Antrim Ireland (1789)

- Johnstone Family Mausoleum, Ochil Road graveyard, Alva, Clackmannanshire (1789–90)

- Johnstone Family Mausoleum, Westerkirk graveyard, near Bentpath, Dumfries and Galloway (1790)

City Homes and Buildings

- Little Wallingford House, Whitehall, London, changes (1761) – now gone.

- Lansdowne House, Berkeley Square, London (1762–67) – partly gone.

- 34 Pall Mall, London (1765–66) – now gone.

- Langford House, Mary Street, Dublin, Ireland (1765) – now gone.

- 16 Hanover Square, London, changes (1766–67) – now gone.

- Deputy Ranger's lodge, Green Park, London (1768–71) – now gone.

- The Adelphi development, London (1768–1775) – mostly gone.

- Chandos House, London (1770–71)

- 8 Queen Street, Edinburgh (1770–71) – now the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

- Mansfield Street, London (1770–72)

- Northumberland House, London, changes (1770) – now gone.

- 20 St. James's Square (1771–74)

- 33 St. James's Square (1771–73)

- Ashburnham House, Dover Street, London, changes (1773)

- Derby House, 26 Grosvenor Square (1773–74) – now gone.

- Portland Place, London (1773–94) – only a few houses remain.

- 11 St. James's Square (1774–76)

- Frederick's Place, London (1775–78)

- Roxburghe House, Hanover Square, London (1776–78) – now gone.

- Home House, London (1777 – before 1784)

- 31 (now 17) Hill Street, London, changes (1777–79)

- Apsley House, London (1778) – altered.

- Cumberland House, Pall Mall, London, changes (1780–88) – now gone.

- Marlborough House, Brighton (1786)

- Fitzroy Square, London (1790–94) – only south and east sides built.

- Charlotte Square (north side), Edinburgh (1791–94)

- 169–185 High Street, Glasgow (1793) – now gone.

- 1–3 Robert Street

Country Houses (Major Work)

- Dumfries House, Ayrshire (1754–1759)

- Hatchlands Park, Surrey, interiors (1756)

- Douglas Castle, Lanarkshire (1757–1761)

- Paxton House, near Berwick-upon-Tweed (1758)

- Shardeloes, Amersham (1759–63)

- Harewood House, West Yorkshire (1759–1771)

- Kedleston Hall, near Derby (1759–1765)

- Mellerstain House, Kelso (1760–1768)

- Ugbrooke, Devon

- Osterley Park, west London (1761–1780)

- Mersham le Hatch, Mersham (1762–1766)

- Syon House interior, Brentford (1762–1769)

- Luton Hoo, Bedfordshire (1766–1770) – later changed.

- Nostell Priory (1766–80)

- Newby Hall, Newby Boroughbridge (1767–76)

- Kenwood House, Hampstead, London (1768)

- Saltram House, Plymouth (1768–69)

- Bowood House, near Calne, Wiltshire (1770)

- Wedderburn Castle, Duns (1770–1778)

- Culzean Castle, South Ayrshire (1772–1790)

- Moreton Hall, Suffolk (1773–1776)

- Stowe, Buckinghamshire (1774)

- Moreton Hall, Bury St Edmund (1783)

- Brasted Place, Kent (c. 1783)

- Pitfour Castle, Tayside, attributed (c. 1785–90)

- Seton Castle, East Lothian (1789)

- Newliston, Lothian (1789)

- Dalquharran Castle, South Ayrshire (1789–1792) – now a ruin.

- Airthrey Castle, Stirlingshire (1790–1791)

- Balbardie House, Lothian (1792) – now gone.

- Gosford House, near Longniddry, East Lothian (1790–1800)

Garden Buildings and Follies

- Stables, Inveraray Castle, with his brother John (1758–60)

- North Lodge, Kedleston Hall (1759)

- Circular and Octagon pavilion, La Trappe, Hammersmith (1760) – now gone.

- Conservatory Croome Park (1760)

- Rotunda Croome Park, attributed (1760)

- Old Rectory, Kedleston Hall (c. 1761)

- Entrance screen, Moor Park, Hertfordshire (1763)

- The Conservatory, Osterley Park (1763)

- Bridge, Audley End House, Essex (c. 1763–64)

- Tea Pavilion, Moor Park, Hertfordshire (c. 1764)

- Gatehouse Kimbolton Castle (c. 1764)

- Bridge, Kedleston Hall (1764)

- Estate Village Lowther, Cumbria (1766)

- Dunstall 'Castle' and Garden Alcove, Croome Park (1766)

- Entrance arch, Croome Court (1767)

- Entrance Screen, Cullen House, Cullen, Moray (1767)

- Bridge, Osterley Park (c. 1768)

- Entrance screen, Syon House (1769)

- Fishing, Boat & Bath House, Kedleston Hall (1770–71)

- Circular Temple, Audley End House, Essex (1771)

- Lion Bridge, Alnwick (1773)

- Stag Lodge, Saltram House, Devon (c. 1773)

- The Stables, Featherstone entrance & Huntwick arch Nostell Priory (1776)

- Wyke Green Lodges, Osterley, Middlesex (1777) – remodeled.

- The Home Farm, Culzean Castle, Ayrshire (1777–79)

- Brizlee Tower, Alnwick, Gothic tower (1777–81)

- Oswald's Temple, Auchincruive, Ayrshire (1778)

- 'Ruined' arch and viaduct, Culzean Castle (1780)

- The semi-circular conservatory, Osterley Park (1780)

- Tea House Bridge, Audley End House, Essex (1782)

- The Stables, Culzean Castle (c. 1785)

- Stables, Castle Upton, Templepatrick, Co. Antrim, Ireland (1788–89)

- Montagu Bridge, Dalkeith Palace, Lothian (1792)

- Loftus Hall, Fethard-on-sea, Co. Wexford, Ireland. Proposed gates.

- Lion Gate and Lodge, Syon Park, London.

Country Houses (Minor Work)

- Hopetoun House, West Lothian (interiors) (1750–54)

- Ballochmyle House, Ayrshire (c. 1757–60)

- Compton Verney House, added wings and interiors (1760–63)

- Croome Park, three interiors (1760–65)

- Audley End House, redecoration of ground floor rooms (1763–65)

- Goldsborough Hall, near Knaresborough (1764–1765)

- Alnwick Castle, Northumberland (interiors) (1766) – destroyed.

- Woolton Hall, Woolton (1772) – remodeled.

- Headfort House, County Meath, Ireland. Internal work (1775).

- Wormleybury, Hertfordshire, internal work (1777).

- Downhill, near Coleraine, County Londonderry, Ireland (1780) – design not built.

- Moccas Court, Moccas, Herefordshire, internal work (1781).

- Castle Upton, Templepartick, Co. Antrim, Ireland. Remodeling of house (1782–83).

- Archerfield House, Lothian, internal work (1791).

- Summerhill House, Co. Meath, Ireland (1765) – proposed changes not built.

Images for kids

-

Coutts Bank, John Adam Street, demolished and replaced with this building

-

Fireplace, Round room, Strawberry Hill House, Middlesex

-

Wedderburn Castle, Berwickshire

-

Harewood House, Yorkshire, altered by Sir Charles Barry

Official Appointments

| Parliament of Great Britain (1707–1800) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Robert Colvile (to 1761) |

Member of Parliament for Kinross-shire 1768–1774 |

Succeeded by George Graham (from 1780) |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by New appointment |

Architect of the King's Works 1761–1769 Served alongside: Sir William Chambers |

Succeeded by Sir Robert Taylor and James Adam |

See also

In Spanish: Robert Adam para niños

In Spanish: Robert Adam para niños

- Adam style

- Category:Robert Adam buildings

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |